Talbot Resolves

| Talbot Resolves | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolution | |||

Historic marker for Talbot Resolves | |||

| Date | May 24, 1774 | ||

| Location | Easton, Maryland, U.S. 38°46′29.5″N 76°4′36.5″W / 38.774861°N 76.076806°W | ||

| Caused by | Boston Port Act | ||

| Goals | To protest British Parliament's closing of the Port of Boston as punishment for the Boston Tea Party. | ||

| Parties | |||

| Lead figures | |||

Matthew Tilghman | |||

The Talbot Resolves was a proclamation made by Talbot County citizens of the British Province of Maryland, on May 24, 1774. The British Parliament had decided to blockade Boston Harbor as punishment for a protest against taxes on tea. The protest became known as the Boston Tea Party. The Talbot Resolves was a statement of support for the city of Boston in the Province of Massachusetts Bay.

The author of the Talbot Resolves is unknown. Speculation has been made that the author is Matthew Tilghman or a group of citizens that included Tilghman, Edward Lloyd IV, Nicholas Thomas, and Robert Goldsborough IV. All four were leading citizens of Talbot County, and they represented the county in a meeting of all of Maryland's counties held in June shortly after the reading of the Talbot Resolves.

Within the next 14 months, statements or resolves were issued elsewhere in the colonies. The First and Second Continental Congresses met, and the American Revolutionary War began. A Declaration of Independence was made on July 4, 1776, and a new independent government for the state of Maryland was formed.

Background

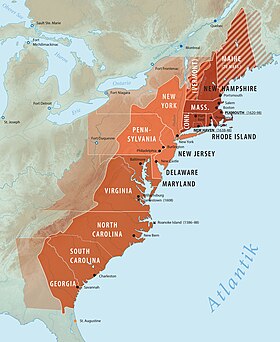

A charter for the Province of Maryland was issued to Lord Baltimore in 1632 by the king of England.[1] The colony became part of a group of English (later British) colonies located along the east coast of North America.[2] During the 1760s after the French and Indian War, Great Britain began imposing taxes on its North American colonies.[3] From the British point of view, the colonies were being taxed to cover the cost of the British Army protecting them.[4] Taxes related to the American Revenue Act 1764 and Stamp Act 1765 caused discontent in the colonies.[5] The major objection was that the taxes were being imposed on the colonists by politicians that did not represent colonists. A slogan often used by the colonists was "no taxation without representation".[6]

Protests against taxes

A popular pamphlet written by Maryland lawyer Daniel Dulany in 1765 was called Considerations on the Propriety of Imposing Taxes in the British Colonies. Although this pamphlet complained mostly against the Stamp Act, it also noted that the restriction on the colonial export of tobacco to countries other than Great Britain was costing farmers money.[7] Notable incidents of violence that occurred between 1765 and 1767 happened at Pokomoke, Maryland; Dighton, Massachusetts; Boston, Massachusetts; Newbury, Massachusetts; and Charlestown, South Carolina. These events typically happened between customs officers and locals.[8]

In Talbot County, Maryland, a group of unknown citizens released "Resolutions of the Freemen of Talbot County Maryland" on November 25, 1765—nearly a decade before the release of the Talbot Resolves. They assembled at the county court house, and declared loyalty to King George III. They also declared that they should enjoy the same rights as British subjects. The remainder of their proclamation complained about the Stamp Act. They also declared that they would erect a gallows ("gibbet") in front of the court house door with an effigy of a stamp informer hung in chains, which would remain until the Stamp Act was repealed.[9] On March 18, 1766, Parliament repealed the Stamp Act, but it also passed the Declaratory Act—which reasserted that Parliament had authority and control in the American colonies.[10]

In 1767, Parliament passed the Townshend Acts which added different types of taxes which were used to fund colonial governors and judges.[3] Among the new law's provisions was an import tax on items such as glass, paper, and tea—all of which had to be imported from Britain.[11] The act reinvigorated dissent.[3] In March 1770, British troops fired on an angry mob of colonists in what became known as the Boston Massacre.[3] During the same month, many of the taxes from the Townshend Acts were repealed. An exception was the tax on tea.[11]

Boston Tea Party

Effective May 10, 1773, the Tea Act 1773 went into effect. This act was designed to assist the financially troubled British East India Company and enable tea to enter North America priced lower than the tea typically smuggled in to avoid taxes.[3] Colonists recognized that by buying this lower-cost tea, and paying the import tax from the Townshend Acts, they would be setting a precedent of abiding by a type of tax they believed unfair.[12]

On December 16, 1773, a protest led mostly by the Sons of Liberty was conducted in Boston Harbor. Men dressed as Native Americans boarded a British East India Company ship in the harbor at night and destroyed its entire shipment of tea by throwing it into the water.[3] The December 16 incident became known as the Boston Tea Party, and it led to defiance in other colonies and similar protests.[3] Over the next few weeks, tea from the British East India Company was rejected at ports in Charleston, New York, and Philadelphia.[13] Later in the year, citizens of Annapolis, Maryland, had their own tea party. On October 19, 1774, the owner of the Maryland cargo ship Peggy Stewart was forced to burn his ship, with its cargo of tea, at the port of Annapolis.[14]

British Parliament reacted to the Boston Tea Party by passing a group of punitive laws aimed at Massachusetts called the Coercive Acts. In the North America the Coercive Acts became known as the Intolerable Acts. The first of this group of acts was the Boston Port Act, which closed Boston's port.[15] British leadership hoped their punishment for Massachusetts would cause other colonies to tone down their resistance to authority. Instead, the acts caused the Thirteen Colonies to unite in defiance, leading to the American Revolution and the American Revolutionary War.[15]

The Resolves

The Talbot Resolves was a proclamation in support of the citizens of Boston. It was read by leading citizens of Talbot County at Talbot Court House on May 24, 1774.[16][Note 1] The statement was read in response to the British plan to close the Port of Boston on June 1 as punishment for the Boston Tea Party protest.[16] Not all of the region's residents agreed with the proclamation. Residents of Maryland's Eastern Shore of the Chesapeake Bay were a mixture of revolutionaries, loyalists, and neutralists. They typically "rejected outside influences" of all types, and some believed that a cause concerning Boston did not have to be a cause of Maryland.[18]

John Thomas Scharf, a 19th-century historian and author of a history of Maryland, wrote that "...no county was more decided in its action than Talbot.[19][Note 2] Another author wrote that the May 24 meeting in Talbot County was "among the very earliest" of those type of "meetings held in Maryland".[21] Statements similar to the Talbot Resolves were made elsewhere in the British North American colonies. George Washington and George Mason were involved with the Fairfax Resolves.[22] In Massachusetts, the Suffolk Resolves were composed.[23]

Creation of the Talbot Resolves

It is believed that in 1958 Baltimore writer Neil H. Swanson was the first to call the statement made at Talbot Court House the Talbot Resolves.[24] The earliest record of the Talbot Resolves is at the bottom of page 3 in the September 2, 1774, edition of the Maryland Gazette. The word "resolve" is nowhere to be found in the article.[25] On the same newspaper page is another article that lists a statement made by the citizens of Chester Town, and it makes liberal use of the term "resolved".[20][Note 3] A summary paragraph of the Chester Town proclamation, in a paragraph above the Talbot Court House statement and below the Chester Town statement, says "The above resolves were entered into upon a discovery of a late importation of the dutiable tea...."[20]

No record is known to exist of the men at the meeting that produced the Talbot Resolves. Matthew Tilghman of Rich Neck Manor, a future member of the First Continental Congress, is the person said to have called the meeting on the courthouse lawn.[16] On June 22, Tilghman, Edward Lloyd IV of Wye House, Nicholas Thomas of Anderton, and Robert Goldsborough IV of Myrtle Grove represented Talbot County's committee of correspondence. They met in Annapolis with similar committees from other Maryland counties.[27][Note 4] It is possible, some say probable, that Tilghman and/or the other three men elected as representatives wrote the document.[16][Note 5]

|

The Talbot Resolves To preserve the rights and to secure the property of the subject, they apprehend is the end of government. But when those rights are invaded—when the mode prescribed by the laws for the punishment of offences and obtaining justice is disregarded and spurned—when without being heard in their defence, force is employed in the severest penalties inflicted; the people, they clearly perceive, have a right not only to complain, but like–wise to exert their utmost endeavors to prevent the effect of such measures as may be adopted by a weak and corrupt ministry to destroy their liberties, to deprive them of their property and rob them of the dearest birthright as Britons. Impressed with the warmest zeal for and loyalty to their most gracious sovereign, and with the most sincere affection for their fellow subjects in Great Britain, they have determined calmly and steadily to unite with their fellow subjects in pursuing every legal and constitutional measure to avert the evils threatened by the late act of Parliament for shutting up the port of Boston; to support the common rights of America and to promote the union and harmony between the mother country and the colonies on which the preservation of both must finally depend.[29] |

Aftermath

In June 1774, Tilghman, Lloyd, Thomas, and Goldsborough represented Talbot County in a convention of Providence of Maryland counties held in Annapolis. Tilghman was elected as chairman of the convention. A series of resolutions condemning recent acts of Parliament were made.[30] Another resolution made was that a general congress of all of the colonies should meet in Philadelphia during September—"a firm union of sister colonies".[23] Tilghman was among those selected to represent Maryland in Philadelphia, and this meeting became known as the First Continental Congress.[30] The Philadelphia meeting of the First Continental Congress began on September 5, 1774, and it continued into October. A boycott of British goods was threatened, and statements explaining the position of the colonies were issued.[31]

The Second Continental Congress met in Philadelphia on May 10, 1775. By this time, the American Revolutionary War had begun. On July 4, 1776, the Second Continental Congress approved and signed "The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America", which later became known in the United States as the Declaration of Independence.[31]

Tilghman again was one of the representatives of Maryland in the Second Continental Congress, but was unable to sign the Declaration because he returned to Maryland to lead its government. In 1781 the Chesapeake Bay was patrolled by British warships, making it necessary for Maryland to split its government into territory west of the bay and territory east of the bay (Maryland's Eastern Shore). This temporary Eastern Shore government met in Easton, Maryland, and Tilghman became its president.[32] He resigned from all government activities in 1783 after the end of the American Revolutionary War, and died May 5, 1790.[33]

Edward Lloyd IV continued to be involved in Maryland politics until his death in 1796.[34] He was also a delegate for the state of Maryland to the Congress of the United States for 1783 and 1784.[35] Robert Goldsborough IV continued his involvement in Maryland politics, and he was a judge in Maryland General Court from 1784 to 1798. He died in 1798.[36] Lawyer Nicholas Thomas represented Talbot County in Maryland's Lower House, and was house speaker from 1777 through 1778. He was involved with the Talbot County Militia during 1776, and a judge in General Court from 1778 to 1782. He died in 1784.[37]

Notes

Footnotes

- ^ Talbot Court House was the name of the village that surrounded Talbot County's courthouse beginning in 1712. An Act from 1785 named the town Talbot, but another Act from 1788 changed the town's name to Easton. It is believed that the name Easton evolved from "East Town", since the community was once the seat of Maryland government for the state's territory east of Chesapeake Bay (a.k.a. Maryland's Eastern Shore).[17]

- ^ Sharf also wrote that Talbot County had the earliest response.[19] That might not be true because at the top of the same Maryland Gazette page that contained the Talbot Court House statement is a similar (although longer) resolution released by Chester Town, Maryland that is dated earlier—May 19, 1774. Although the Chester Town document condemns the tax on tea, it does not mention Boston.[20]

- ^ Local lore, unsubstantiated, says that the Chester Town Resolves were drafted in response to the Boston Tea Party, and a Chestertown Tea Party mimicking the Boston Tea Part occurred during May 1774 when tea was thrown into the Chester River.[26]

- ^ The purpose of each county's committee of correspondence was to "give guidance to any political movements and hold communication with bodies of the same kind wherever they had been organized throughout the colonies".[27]

- ^ Matthew Tilghman's nephew is Tench Tilghman, who was an aide-de-camp for General George Washington during the American Revolutionary War. The family also included loyalists.[28]

Citations

- ^ Hall 1902, p. 29

- ^ Samuel Dunn and Robert Sayer (1774). A Map of the British empire in North America (Map). London: Robert Sayer. Retrieved September 3, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g "The Boston Tea Party". American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved August 28, 2024.

- ^ Knollenberg 1975, p. 42

- ^ Knollenberg 1975, pp. 2, 14

- ^ ""No Taxation Without Representation"". American Battlefield Trust. Archived from the original on September 12, 2024. Retrieved September 12, 2024.

- ^ Knollenberg 1975, pp. 32–33

- ^ Knollenberg 1975, p. 61

- ^ Tilghman & Harrison 1915, pp. 44–45

- ^ "Parliament - an Act Repealing the Stamp Act; March 18, 1766". American Battlefield Trust. Archived from the original on July 15, 2024. Retrieved September 27, 2024.; "Declaratory Act". American Battlefield Trust. Archived from the original on May 22, 2024. Retrieved September 27, 2024.

- ^ a b "Townshend Act 1767". American Battlefield Trust. Archived from the original on July 16, 2024. Retrieved September 12, 2024.

- ^ Knollenberg 1975, p. 95

- ^ Knollenberg 1975, p. 102

- ^ "Burning of the Peggy Steward - The Annapolis Tea Party". Maryland State House. Archived from the original on September 13, 2024. Retrieved September 13, 2024.

- ^ a b "The Intolerable Acts". American Battlefield Trust. Archived from the original on August 24, 2024. Retrieved September 12, 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Talbot County Commemorates the 250th Anniversary of the Talbot Resolves". Star-Democrat (Easton, Maryland). Adams Publishing Group. May 29, 2024. Retrieved September 3, 2024.

- ^ "History of Easton, Maryland". Town of Easton, Maryland. Archived from the original on September 4, 2024. Retrieved September 3, 2024.

- ^ Neville 2009, p. 140

- ^ a b Scharf 1879, p. 148

- ^ a b c "Chester Town, May 19, 1774 - To the Printers of the Maryland Gazette (top of page 3)". Maryland Gazette. Anne Catharine Green and Son. June 6, 1774. Archived from the original on September 4, 2024. Retrieved September 2, 2024.

- ^ Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 60

- ^ "Fairfax County Resolves, 18 July 1774". National Historical Publications and Records Commission, U.S. National Archives. Retrieved September 14, 2024.; Warford-Johnston 2016, p. 88

- ^ a b Warford-Johnston 2016, p. 88

- ^ Preston, Dickson (May 22, 1974). "Talbot Yesterday - Were there any Talbot Resolves?". Star-Democrat (Easton, Maryland).

In 1958, a Baltimore writer and lecturer named Neil H. Swanson came across the Talbot statement. He appears to have been the first to call it the "Talbot Resolves".

- ^ "Talbot Court House, May 24, 1774 (bottom of page 3)". Maryland Gazette. Anne Catharine Green and Son. June 6, 1774. Archived from the original on September 4, 2024. Retrieved September 2, 2024.

- ^ "Chestertown Tea Party: Fact or Fiction". Edward H. Nabb Research Center - Salisbury University. Archived from the original on September 6, 2024. Retrieved September 6, 2024.

- ^ a b Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 61; Weeks, Bourne & Maryland Historical Trust 1984, p. 78

- ^ "Archives of Maryland - Tench Tilghman (1744-1786)". Maryland State Archives. Archived from the original on September 28, 2024. Retrieved September 14, 2024.

- ^ Weeks, Bourne & Maryland Historical Trust 1984, p. 78

- ^ a b Tilghman & Harrison 1915a, p. 426

- ^ a b "Continental Congress, 1774–1781". Office of the Historian, Department of State, United States of America. Archived from the original on June 25, 2024. Retrieved September 13, 2024.

- ^ Tilghman & Harrison 1915a, pp. 427–428

- ^ Tilghman & Harrison 1915a, p. 428; "Tilghman, Matthew 1718-1790". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, Library of Congress. Retrieved August 18, 2024.

- ^ Tilghman & Harrison 1915a, pp. 176, 180

- ^ Tilghman & Harrison 1915a, p. 180

- ^ "Archives of Maryland - Robert Goldsborough IV (1740-1798)". Maryland State Archives. Archived from the original on September 28, 2024. Retrieved September 13, 2024.

- ^ "Archives of Maryland - Nicholas Thomas (d. 1784)". Maryland State Archives. Archived from the original on June 15, 2024. Retrieved September 13, 2024.

References

- Hall, Clayton Colman (1902). The Lords Baltimore and the Maryland Palatinate: Six Lectures on Maryland Colonial History Delivered Before the Johns Hopkins University in the Year 1902. Baltimore: J. Murphy Co. OCLC 3564975. Archived from the original on September 4, 2024. Retrieved September 1, 2024.

- Knollenberg, Bernhard (1975). Growth of the American Revolution, 1766–1775. New York: Free Press. ISBN 978-0-02917-110-3. OCLC 979186. Retrieved August 30, 2024.

- Neville, Barry Paige (2009). "For God, King, and Country: Loyalism on the Eastern Shore of Maryland During the American Revolution". International Social Science Review. 84 (3/4). Oakville, Ontario: Pi Gamma Mu (International Social Science Honor Society): 135–156. JSTOR 41887408. Retrieved August 31, 2024.

- Scharf, J. Thomas (1879). History of Maryland: From the Earliest Period to the Present Day. Baltimore: J.B. Piet. OCLC 4663774. Retrieved September 2, 2024.

- Tilghman, Oswald; Harrison, Samuel A. (1915a). History of Talbot County, Maryland, 1661-1861, Volume I. Baltimore, Maryland: Williams and Wilkins Company. OCLC 1541072. Archived from the original on September 4, 2024. Retrieved August 17, 2024.

- Tilghman, Oswald; Harrison, Samuel A. (1915). History of Talbot County, Maryland, 1661-1861, Volume II. Baltimore, Maryland: Williams and Wilkins Company. OCLC 1541072. Archived from the original on December 17, 2021. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- Warford-Johnston, Benjamin (November 2016). "American Colonial Committees of Correspondence: Encountering Oppression, Exploring Unity, and Exchanging Visions of the Future". The History Teacher. 50 (1). Long Beach, California: Society for History Education: 83–128. JSTOR 44504455. Retrieved September 14, 2024.

- Weeks, Christopher; Bourne, Michael O.; Maryland Historical Trust (1984). Where Land and Water Intertwine: An Architectural History of Talbot County, Maryland. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-80183-165-2. OCLC 10696846.

External links

- Talbot County history – Talbot County, Maryland

- Talbot County chronology - Maryland Manual Online