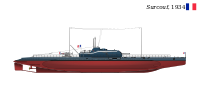

French submarine Surcouf

Surcouf c. 1935 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Surcouf |

| Namesake | Robert Surcouf |

| Ordered | 4 August 1926 |

| Builder | Cherbourg Arsenal |

| Laid down | 1 July 1927 |

| Launched | 18 November 1929 |

| Commissioned | 16 April 1934 |

| In service | 1934–1942 |

| Refit | 1941 |

| Identification |

|

| Honors and awards | Resistance Medal with rosette |

| Fate | Disappeared, 18 February 1942 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Cruiser submarine |

| Displacement |

|

| Length | 110 m (361 ft) |

| Beam | 9 m (29 ft 6 in) |

| Draft | 7.25 m (23 ft 9 in) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed |

|

| Range | |

| Endurance | 90 days |

| Test depth | 80 m (260 ft) |

| Boats & landing craft carried | 2 × motorboats in watertight deck well |

| Capacity | 280 long tons (284 t) |

| Complement | 8 officers and 110 men |

| Armament |

|

| Aircraft carried | 1 × Besson MB.411 floatplane |

| Aviation facilities | Hangar |

Surcouf [syʁ.kuf] was a large French gun-armed cruiser submarine of the mid 20th century. She carried two 203 mm guns as well as anti-aircraft guns and (for most of her career) a floatplane. Surcouf served in the French Navy and, later, the Free French Naval Forces during the Second World War.

Surcouf disappeared during the night of 18/19 February 1942 in the Caribbean Sea, possibly after colliding with the US freighter Thompson Lykes, although this has not been definitely established. She was named after the French privateer and shipowner Robert Surcouf. She was the largest submarine built until surpassed by the first Japanese I-400 class aircraft carrier submarine in 1944.

Design

The Washington Naval Treaty had placed strict limits on naval construction by the major naval powers in regard to displacements and artillery calibers of battleships and cruisers. However, no agreements were reached in respect of light ships such as frigates, destroyers or submarines. In addition, to ensure the country's protection and that of the empire, France started the construction of an important submarine fleet (79 units in 1939). Surcouf was intended to be the first of a class of three submarine cruisers; however, she was the only one completed.

The missions revolved around:

- Ensuring contact with the French colonies;

- In collaboration with French naval squadrons, searching for and destroying enemy fleets;

- Pursuing enemy convoys.

Surcouf had a twin-gun turret with 203 mm (8-inch) guns, the same calibre as the guns of a heavy cruiser, provisioned with 60 rounds. She was designed as an "underwater heavy cruiser", intended to seek out and engage in surface combat.[2] The boat carried a Besson MB.411 observation floatplane in a hangar built aft of the conning tower for reconnaissance and observing fall of shot.

The boat was equipped with ten torpedo tubes: four 550 mm (22 in) tubes in the bow, and two swiveling external launchers in the aft superstructure, each with one 550 mm and two 400 mm (16 in) torpedo tubes. Eight 550 mm and four 400 mm reloads were carried.[3] The 203 Modèle 1924 guns were in a pressure-tight turret forward of the conning tower. The guns had a 60-round magazine capacity and were controlled by a director with a 5 m (16 ft) rangefinder, mounted high enough to view an 11 km (5.9 nmi; 6.8 mi) horizon, and able to fire within three minutes after surfacing.[4] Using the boat's periscopes to direct the fire of the main guns, Surcouf could increase the visible range to 16 km (8.6 nmi; 9.9 mi); originally an elevating platform was supposed to lift lookouts 15 m (49 ft) high, but this design was abandoned quickly due to the effect of roll.[5] The Besson observation plane could be used to direct fire out to the guns' 26 mi (23 nmi; 42 km) maximum range. Anti-aircraft cannon and machine guns were mounted on the top of the hangar.

Surcouf also carried a 4.5 m (14 ft 9 in) motorboat, and contained a cargo compartment with fittings to restrain 40 prisoners or lodge 40 passengers. The submarine's fuel tanks were very large; having enough fuel for a 10,000 nmi (19,000 km; 12,000 mi) range and supplies for 90-day patrols.

The test depth was 80 m (260 ft).

The first commanding officer was Frigate Captain (Capitaine de Frégate, a rank equivalent to Commander) Raymond de Belot.

The boat encountered several technical challenges:

- Because of the low height of the rangefinder above the water surface, the practical range of fire was 12,000 m (13,000 yd) with the rangefinder, increased to 16,000 m (17,000 yd) with sighting aided by periscope, well below the guns' maximum range of 26,000 m (28,000 yd).

- The duration between the surface order and the first firing round was 3 minutes and 35 seconds. This duration would be longer if the boat was to fire broadside, which meant surfacing and training the turret in the desired direction.

- Firing had to occur at a precise moment of pitch and roll when the ship was level.

- Training the turret to either side was impossible when the ship rolled 8° or more.

- Surcouf could not fire accurately at night, as fall of shot could not be observed in the dark.

- The guns' ready magazines had to be reloaded after firing 14 rounds from each gun.

To replace the floatplane, whose functioning was initially constrained and limited in use, trials were conducted with an autogyro in 1938.

Appearance

'From the beginning of the boat's career until 1932, the boat was painted the same grey colour as surface warships, but thereafter in Prussian dark blue, a colour which was retained until the end of 1940 when it was repainted with two tones of grey, serving as camouflage on the hull and conning tower.

- Original configuration, 1932

- 1934 configuration, with Prussian blue paintwork

- 1938 configuration: radio mast removed and different conning tower

- 1940 configuration, with two-tone gray paint and 17P identification number on the conning tower

Career

Early career

Soon after Surcouf was launched, the London Naval Treaty finally placed restrictions on submarine designs. Among other things, each signatory (France included) was permitted to possess no more than three large submarines, each not exceeding 2,800 long tons (2,845 t) standard displacement, with guns not exceeding 6.1 in (150 mm) in caliber. Surcouf, which would have exceeded these limits, was specially exempt from the rules at the insistence of Navy Minister Georges Leygues,[4] but other 'big-gun' submarines of this boat's class could no longer be built.

Second World War

| Seizure of Surcouf | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War II | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 3 killed | 1 killed | ||||||

In 1940, Surcouf was based in Cherbourg, but in May, when the Germans invaded, she was being refitted in Brest following a mission in the Antilles and Gulf of Guinea. Under command of Frigate Captain Martin, unable to dive and with only one engine functioning and a jammed rudder, she limped across the English Channel and sought refuge in Plymouth.

On 3 July, the British, concerned that the French Fleet would be taken over by the German Kriegsmarine at the French armistice, executed Operation Catapult. The Royal Navy blockaded the harbours where French warships were anchored, and delivered an ultimatum: rejoin the fight against Germany, be put out of reach of the Germans, or scuttle. Few accepted willingly; the North African fleet at Mers-el-Kebir and the ships based at Dakar (French West Africa) refused. The French battleships in North Africa were eventually attacked and all but one sunk at their moorings by the Mediterranean Fleet.

French ships lying at ports in Britain and Canada were also boarded by armed marines, sailors and soldiers, but the only serious incident took place at Plymouth aboard Surcouf on 3 July, when two Royal Navy submarine officers, Commander Denis 'Lofty' Sprague, captain of HMS Thames, and Lieutenant Patrick Griffiths of HMS Rorqual,[6][7] and French warrant officer mechanic Yves Daniel[8] were fatally wounded, and a British seaman, Albert Webb,[6] was shot dead by the submarine's doctor.[9]

Free French Naval Forces

By August 1940, the British completed Surcouf's refit and turned her over to the Free French Naval Forces (Forces Navales Françaises Libres, FNFL) for convoy patrol. The only officer not repatriated from the original crew, Frigate Captain Georges Louis Blaison, became the new commanding officer. Because of Anglo-French tensions with regard to the submarine, accusations were made by each side that the other was spying for Vichy France; the British also claimed Surcouf was attacking British ships. Later, a British officer and two sailors were put aboard for "liaison" purposes. One real drawback was she required a crew of 110–130 men, which represented three crews of more conventional submarines. This led to Royal Navy reluctance to recommission her.

Surcouf then went to the Canadian base at Halifax, Nova Scotia and escorted trans-Atlantic convoys. In April 1941, she was damaged by a German plane at Devonport.[8]

On 28 July, Surcouf went to the United States Naval Shipyard at Kittery, Maine for a three-month refit.[4]

After leaving the shipyard, Surcouf went to New London, Connecticut, perhaps to receive additional training for her crew. Surcouf left New London on 27 November to return to Halifax.

Capture of St. Pierre and Miquelon

In December 1941, Surcouf carried the Free French Admiral Émile Muselier to Canada, putting into Quebec City. While the Admiral was in Ottawa, conferring with the Canadian government, Surcouf's captain was approached by The New York Times reporter Ira Wolfert and questioned about the rumours the submarine would liberate Saint-Pierre and Miquelon for Free France. Wolfert accompanied the submarine to Halifax, where, on 20 December, they joined Free French "Escorteurs" corvettes Mimosa, Aconit, and Alysse, and on 24 December, took control of the islands for Free France without resistance.

United States Secretary of State Cordell Hull had just concluded an agreement with the Vichy government guaranteeing the neutrality of French possessions in the Western hemisphere, and he threatened to resign unless President of the United States Franklin D. Roosevelt demanded a restoration of the status quo. Roosevelt did so, but when Charles de Gaulle refused, Roosevelt dropped the matter. Ira Wolfert's stories – very favourable to the Free French (and bearing no sign of kidnapping or other duress) – helped swing American popular opinion away from Vichy. The Axis Powers' declaration of war on the United States in December 1941 negated the agreement, but the U.S. did not sever diplomatic ties with the Vichy Government until November 1942.

Later operations

In January 1942, the Free French leadership decided to send Surcouf to the Pacific theatre, after she had been re-supplied at the Royal Naval Dockyard in Bermuda. However, her movement south triggered rumours that Surcouf was going to liberate Martinique from the Vichy regime.

In fact, Surcouf was bound for Sydney, Australia, via Tahiti.[4] She departed Halifax on 2 February for Bermuda, which she left on 12 February, bound for the Panama Canal.[8]

Fate

Surcouf vanished on the night of 18/19 February 1942, about 130 km (70 nmi) north of Cristóbal, Panama, while en route for Tahiti, via the Panama Canal. An American report concluded the disappearance was due to an accidental collision with the American freighter Thompson Lykes. Steaming alone from Guantanamo Bay on what was a very dark night, the freighter reported hitting and running down a partially submerged object which scraped along her side and keel. Her lookouts heard people in the water but, thinking she had hit a U-boat, the freighter did not stop although cries for help were heard in English. A signal was sent to Panama describing the incident.[10][11]

The loss resulted in 130 deaths (including 4 Royal Navy personnel), under the command of Frigate Captain Georges Louis Nicolas Blaison.[12] The loss of Surcouf was announced by the Free French Headquarters in London on 18 April 1942, and was reported in The New York Times the next day.[13] It was not reported Surcouf was sunk as the result of a collision with the Thompson Lykes until January 1945.[14]

The investigation of the French commission concluded the disappearance was the consequence of misunderstanding. A Consolidated PBY, patrolling the same waters on the night of 18/19 February, could have attacked Surcouf believing her to be German or Japanese.

Inquiries into the incident were haphazard and late, while a later French inquiry supported the idea that the sinking had been due to "friendly fire"; this conclusion was supported by Rear Admiral Gabriel Auphan in his book The French Navy in World War II.[15] Charles de Gaulle stated in his memoirs[16] that Surcouf "had sunk with all hands".

Legacy

As no one has officially dived or verified the wreck of Surcouf, her location is unknown. If one assumes the Thompson Lykes incident was indeed the event of Surcouf's sinking, then the wreck would lie 3,000 m (9,800 ft) deep at 10°40′N 79°32′W / 10.667°N 79.533°W.[4]

A monument commemorates the loss in the port of Cherbourg in Normandy, France.[17] The loss is also commemorated by the Free French Memorial on Lyle Hill in Greenock, Scotland.[18]

As there is no conclusive confirmation that Thompson Lykes collided with Surcouf, and her wreck has yet to be discovered, there are alternative stories of her fate. James Rusbridger examined some of these theories in his book Who Sank Surcouf?, finding them all easily dismissible except one: the records of the 6th Heavy Bomber Group operating out of Panama show them sinking a large submarine the morning of 19 February. Since no German submarine was lost in the area on that date, she could have been Surcouf. He suggested the collision had damaged Surcouf's radio and the stricken boat limped towards Panama hoping for the best.[19]

A conspiracy theory, based on no significant evidence, held that the Surcouf, during her stationing at New London in late 1941, had been caught treacherously supplying a German U-boat in Long Island Sound, pursued by the American training subs Marlin and Mackerel out of New London, and sunk. The rumor circulated into the early 21st century, but is false since the Surcouf's later movements south are well documented.[20]

In popular media

The Surcouf is the subject of an underwater search by the fictional organization NUMA and international terrorists in the Clive Cussler novel "The Corsican Shadow", published in 2023. Cussler and his co-writer, Dirk Cussler, writes the Surcouf's wreck was discovered "...some eighty miles off the Panama coast." The sinking is even attributed to Surcouf's radio antenna being damaged in the collision with the Thompson Lykes, and then finished off by the reported attack of an A-17 bomber the next morning.

Honors

- Médaille de la Résistance avec Rosette (Resistance Medal with rosette) - 29 November 1946

- Cited in Orders of Corps of the Army - 4 August 1945

- Cited in Orders of the Navy - 8 January 1947[21]

See also

- French submarines of World War II

- Fusiliers Marins

- Georges Cabanier

- HM Submarine X1

- HMS M2 (1918)

- Japanese I-400-class submarine

- USS Dorado (SS-248) a US submarine sunk in the same area under similar circumstances

- List of submarines of France

- Submarine aircraft carrier

References

- ^ Ross, D. (2016:65). The World's Most Powerful Submarines. United States: Rosen Publishing.

- ^ Winchester, Clarence (1937). Shipping wonders of the world. Vol. 41–55. Amalgamated Press. p. 1431.

- ^ Huan, Claude (1996). Le croiseur sous-marin Surcouf. Bourg en Bresse: Marines editions. pp. 53–54.

- ^ a b c d e Croiseur sous-marin Surcouf, netmarine

- ^ Sous-marin croiseur Surcouf: Caractéristiques principales

- ^ a b Smith, Colin (24 June 2010). England's last war against France: Fighting Vichy 1940–42 (paperback ed.). Phoenix. Chapter 4. ISBN 978-0-7538-2705-5.

- ^ Kindell, Don (12 June 2011), Gordon Smith (ed.), "1st – 31st July 1940", Casualty Lists of the Royal Navy and Dominion Navies, World War 2

- ^ a b c Histoire du sous-marin Surcouf (in French), netmarine

- ^ Brown, David; Till, Geoffrey (2004). The Road to Oran: Anglo-French Naval Relations, September 1939 – July 1940. Routledge. p. 182. ISBN 0-7146-5461-2.

- ^ Morison, Samuel Eliot; Till, Geoffrey (2001). History of United States Naval Operations in World War II: The Rising Sun in the Pacific, 1931 – April 1942. University of Illinois Press. p. 265. ISBN 0-252-06963-3.

- ^ Kelshall, Gaylord; Till, Geoffrey (1994). The U-Boat War in the Caribbean. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. p. 68. ISBN 1-55750-452-0.

- ^ "Blaison Georges Louis Nicolas". memorial-national-des-marins.fr. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ "Free French List Surcouf as Lost". The New York Times. 19 April 1942. p. 36. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- ^ The New York Times. 29 January 1945.

- ^ Auphan, Paul; Mordal, Jacques (1959). The French Navy in World War II. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press.[page needed]

- ^ de Gaulle, Charles (1955). Mordal, Jaques (ed.). The War Memoirs of Charles de Gaulle, Vol. 1 The Call To Honour 1940–1942. Viking Press.[page needed]

- ^ "Ahoy - Mac's Web Log - French Submarine Surcouf, the World's largest Submarine before WW2. Her mysterious disappearance in February of 1942".

- ^ "War Memorials". Inverclyde Council. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

A la memoire du Capitaine de frigate Blaison, des officiers et de l'equipage du sous-marin Surcouf perdu dans l'Atlantique Fevrier 1942

- ^ Rusbridger, James (1991). Who Sank the "Surcouf"?: The Truth About the Disappearance of the Pride of the French Navy. Ebury Press. ISBN 0-7126-3975-6.[page needed]

- ^ John Ruddy (20 November 2016). "French sub's visit to New London launched conspiracy theory". The [New London] Day. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ "N N 3". sous-marin.france.pagesperso-orange.fr. Archived from the original on 2 September 2012. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

Bibliography

External links

- NN3 Specs (in French)

- Surcouf and M.B.411

- War History Online

- [1] Roll of Honor