Modern South Arabian languages

| Modern South Arabian | |

|---|---|

| Eastern South Semitic, Southeastern Semitic | |

| Geographic distribution | Yemen and Oman |

| Linguistic classification | Afro-Asiatic

|

| Subdivisions | |

| Language codes | |

| Glottolog | mode1252 |

| |

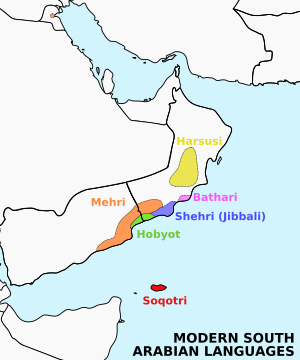

The Modern South Arabian languages (MSALs),[1][2] also known as Eastern South Semitic languages, are a group of endangered languages spoken by small populations inhabiting the Arabian Peninsula, in Yemen and Oman, and Socotra Island. Together with the Ethiosemitic and Sayhadic languages, the Western branch, they form the South Semitic sub-branch of the Afroasiatic language family's Semitic branch.

Mehri and Hobyot are spoken in both Yemen and Oman. Soqotri is only spoken in the Yemeni archipelago of Socotra, and the Harsusi, Bathari, and Shehri languages are only spoken in Oman.[3]

Classification

In his glottochronology-based classification, Alexander Militarev presents the Modern South Arabian languages as a South Semitic branch opposed to a North Semitic branch that includes all the other Semitic languages.[4][5] They are no longer considered to be descendants of the Old South Arabian language, as was once thought, but instead "nephews". Despite the name, they are not closely related to the Arabic language.

Languages

- Mehri: the largest Modern South Arabian language, with over 200,000 speakers.[3] Most Mehri speakers, around 76,000, live in Oman, but around 50,000 live in Yemen, and around 40,000 speakers live as guest workers in Kuwait, The UAE, and Saudi Arabia.[citation needed] A person who speaks the language is referred to as Mahri.[citation needed]

- Soqotri: another relatively numerous examples, with speakers on the island of Socotra isolated from the pressures of Arabic on the Yemeni mainland.[citation needed] In 2015, there were around 70,000 speakers.[citation needed]

- Shehri: frequently called Jibbali, "of the Mountains", with an estimated 25,000 speakers;[citation needed] it is best known as the language of the rebels during the Dhofar Rebellion in Oman's Dhofar Governorate along the border with Yemen in the 1960s and 1970s.[citation needed]

- Bathari: Under 100 speakers in Oman. Located on the southeast coast facing the Khuriya Muriya Islands. Very similar to Mehri, and some tribespeople speak Mehri instead of Bathari.[citation needed]

- Harsusi: 600 speakers in the Jiddat al-Harasis of Oman.[citation needed]

- Hobyót: 100 speakers est., in Oman and Yemen.[citation needed]

Grammar

Modern South Arabian languages are known for their apparent archaic Semitic features, especially in their system of phonology. For example, they preserve the lateral fricatives of Proto-Semitic.

Additionally, Militarev identified a Cushitic substratum in Modern South Arabian, which he proposes is evidence that Cushitic speakers originally inhabited the Arabian Peninsula alongside Semitic speakers (Militarev 1984, 18–19; cf. also Belova 2003). According to Václav Blažek, this suggests that Semitic peoples assimilated their original Cushitic neighbours to the south who did not later emigrate to the Horn of Africa. He argues that the Levant would thus have been the Proto-Afro-Asiatic Urheimat, from where the various branches of the Afro-Asiatic family subsequently dispersed. To further support this, Blažek cites analysis of rock art in Central Arabia by Anati (1968, 180–84), which notes a connection between the shield-carrying "oval-headed" people depicted on the cave paintings and the Arabian Cushites from the Old Testament, who were similarly described as carrying specific shields.[6]

Reconstruction

Proto-Modern South Arabian reconstructions by Roger Blench (2019):[7]

| Gloss | singular | plural |

|---|---|---|

| one | *tʕaad, *tʕiit | |

| two | *ṯrooh, *ṯereṯ | |

| three | *ʃahṯayt | |

| four | *ʔorbac, *raboot | |

| five | *xəmmoh | |

| six | m. *ʃɛɛt, f. *ʃətəət | |

| seven | m. *ʃoobeet, f. *ʃəbət | |

| eight | m. θəmoonit, f. θəmoonit | |

| nine | m. *saʕeet, f. *saaʕet | |

| ten | m. *ʕɔ́ɬər, f. *ʕəɬiireet | |

| head | *ḥəəreeh | |

| eye | *ʔaayn | *ʔaayəəntən |

| ear | *ʔeyðeen | *ʔiðānten |

| nose | *nəxreer | *nəxroor |

| mouth | *xah | *xwuutən |

| hair | *ɬəfeet | *ɬéef |

| hand/arm | *ḥayd | *ḥaadootən |

| leg | *faaʕm | *fʕamtən |

| foot | *géedəl | *(ha-)gdool |

| blood | *ðoor | *ðiiriín |

| breast | *θɔɔdɛʔ | *θədií |

| belly | *hóofəl | *hefool |

| sea | *rɛ́mrəm | *roorəm |

| path, road | *ḥóorəm | *ḥiiraám |

| mountain | *kərmām | *kərəəmoom |

| rock, stone | *ṣar(fét) | *ṣeref |

| rock, stone | *ṣəwər(fet) | *ṣəfáyr |

| rock, stone | *ʔoobən | |

| rock, stone | *fúdún | |

| fish | *ṣódəh | *ṣyood |

| hyena | *θəbiiriin | |

| turtle | *ḥameseh | *ḥoms(tə) |

| louse | *kenemoot | *kenoom |

| man | *ɣayg | *ɣəyuug |

| woman | *teeθ | |

| male child | *ɣeg | |

| child | *mber | |

| water | *ḥəmooh | |

| fire | *ɬəweeṭ | *ɬewṭeen |

| milk | *ɬxoof | *ɬxefən |

| salt | *məɮḥɔ́t | |

| night | *ʔaṣeer | *leyli |

| day | *ḥəyoomet | PWMSA *yiim |

| net | PWMSA *liix | *leyuux |

| wind | *mədenut | *medáyten |

| I, we | *hoh | *nəhan |

| you, m. | *heet | *ʔəteem |

| you, f. | *hiit | *ʔeteen |

| he, they m. | *heh | *həəm |

| she, they f. | *seeh | *seen |

References

- ^ Simeone-Senelle, Marie-Claude (1997). "The Modern South Arabian Languages" (PDF). In Hetzron, R. (ed.). The Semitic Languages. London: Routledge. pp. 378–423. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-07-09. Retrieved 2017-05-12.

- ^ Rendsburg, Gary A. "Modern South Arabian as a source for Ugaritic etymologies". Rutgers University.

- ^ a b Simeone-Senelle, Marie-Claude (2014). "Aaron D. Rubin, The Mehri Language of Oman". Arabian Humanities. 3: 2. doi:10.4000/cy.2703. ISSN 2308-6122.

- ^ "Semitskiye yazyki | Entsiklopediya Krugosvet" Семитские языки | Энциклопедия Кругосвет [Semitic languages | Encyclopedia Around the World] (in Russian).

- ^ Militarev, Alexander. "Once more about glottochronology and the comparative method: the Omotic-Afrasian case" (PDF). Moscow: Russian State University for the Humanities.

- ^ Blažek, Václav. "Afroasiatic Migrations: Linguistic Evidence" (PDF). Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- ^ Blench, Roger (14 December 2019). "Reconstructing Modern South Arabian. Paper presented at the Workshop on Modern South Arabian Languages, Erlangen, Germany".

Bibliography

- Johnstone, T.M. (1975). "The Modern South Arabian Languages". Afroasiatic Linguistics. 1 (5): 93–121.

- Johnstone, T.M. (1977). Ḥarsūsi Lexicon and English-Ḥarsūsi Word-List. London: Oxford University Press.

- Johnstone, T.M. (1981). Jibbāli Lexicon. London: Oxford University Press.

- Johnstone, T.M. (1987). Mehri Lexicon and English-Mehri Word-List. London: School of Oriental and African Studies.

- Nakano, Aki’o (1986). Comparative Vocabulary of Southern Arabic: Mahri, Gibbali, and Soqotri. Tokyo: Institute for the Study of Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa.

- Nakano, Aki’o (2013). Ratcliffe, Robert (ed.). Hōbyot (Oman) Vocabulary: With Example Texts. Tokyo: Research Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa.

- Naumkin, Vitaly; et al. (2014). Corpus of Soqotri Oral Literature. Vol. 1. Leiden: Brill.

- Rubin, Aaron D. (2010). The Mehri Language of Oman. Leiden: Brill.

- Rubin, Aaron D. (2014). The Jibbali Language of Oman: Grammar and Texts. Leiden: Brill.

- Watson, Janet C.E. (2012). The Structure of Mehri. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

External links

- The Modern South Arabian Languages Archived 2016-05-09 at the Wayback Machine, by M.C.Simeone-Senelle