Skylab

Skylab as photographed by its departing final crew (Skylab 4). | |

Skylab program insignia | |

| Station statistics | |

|---|---|

| COSPAR ID | 1973-027A |

| SATCAT no. | 6633 |

| Call sign | Skylab |

| Crew | 3 per mission (9 total) |

| Launch | May 14, 1973 17:30:00 UTC (51 years ago) |

| Carrier rocket | Saturn V AS-513 |

| Launch pad | Kennedy LC-39A |

| Reentry | July 11, 1979 16:37:00 UTC |

| Mission status | Deorbited |

| Mass | 168,750 pounds (76,540 kg)[1] w/o Apollo CSM |

| Length | 82.4 feet (25.1 m) w/o Apollo CSM |

| Width | 55.8 feet (17.0 m) w/ one solar panel |

| Height | 36.3 feet (11.1 m) w/ telescope mount |

| Diameter | 21.67 feet (6.61 m) |

| Pressurised volume | 12,417 cubic feet (351.6 m3) |

| Atmospheric pressure | 5.0 pounds per square inch (34 kPa) Oxygen 74%, nitrogen 26%[2] |

| Perigee altitude | 269.7 miles (434.0 km) |

| Apogee altitude | 274.6 miles (441.9 km) |

| Orbital inclination | 50.0° |

| Orbital period | 93.4 minutes |

| Orbits per day | 15.4 |

| Days in orbit | 2249 days (6.6 years) |

| Days occupied | 171 days |

| No. of orbits | 34,981 |

| Distance travelled | ~890,000,000 mi (1,400,000,000 km) |

| Statistics as of Re-entry July 11, 1979 | |

| Configuration | |

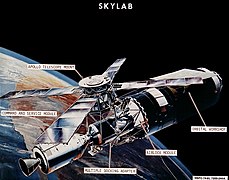

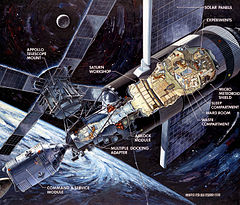

Skylab configuration as planned | |

| Part of a series on the |

| United States space program |

|---|

|

Skylab was the United States' first space station, launched by NASA,[3] occupied for about 24 weeks between May 1973 and February 1974. It was operated by three trios of astronaut crews: Skylab 2, Skylab 3, and Skylab 4. Operations included an orbital workshop, a solar observatory, Earth observation and hundreds of experiments. Skylab's orbit eventually decayed and it disintegrated in the atmosphere on July 11, 1979, scattering debris across the Indian Ocean and Western Australia.

Overview

As of 2025, Skylab was the only space station operated exclusively by the United States. A permanent station was planned starting in 1988, but its funding was canceled and U.S. participation shifted to the International Space Station in 1993.

Skylab had a mass of 199,750 pounds (90,610 kg) with a 31,000-pound (14,000 kg) Apollo command and service module (CSM) attached[4] and included a workshop, a solar observatory, and several hundred life science and physical science experiments. It was launched uncrewed into low Earth orbit by a Saturn V rocket modified to be similar to the Saturn INT-21, with the S-IVB third stage not available for propulsion because the orbital workshop was built out of it. This was the final flight for the rocket more commonly known for carrying the crewed Apollo Moon landing missions.[5] Three subsequent missions delivered three-astronaut crews in the Apollo CSM launched by the smaller Saturn IB rocket.

Configuration

Skylab included the Apollo Telescope Mount (a multi-spectral solar observatory), a multiple docking adapter with two docking ports, an airlock module with extravehicular activity (EVA) hatches, and the orbital workshop, the main habitable space inside Skylab. Electrical power came from solar arrays and fuel cells in the docked Apollo CSM. The rear of the station included a large waste tank, propellant tanks for maneuvering jets, and a heat radiator. Astronauts conducted numerous experiments aboard Skylab during its operational life.

| Component | Mass[5][6][4] | Habitable volume | Length | Diameter | Image | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lb | kg | ft3 | m3 | ft | m | ft | m | ||

| Payload shroud | 25,600 | 11,600 | — | 56.0 | 17.1 | 21.6 | 6.6 | ||

| Apollo Telescope Mount | 24,500 | 11,100 | — | 14.7 | 4.5 | 11.3 | 3.4 |  | |

| Multiple Docking Adapter | 12,000 | 5,400 | 1,140 | 32 | 17.3 | 5.3 | 10.5 | 3.2 |  |

| Airlock module | 49,000 | 22,000 | 613 | 17.4 | 17.6 | 5.4 | 10.5 | 3.2 |  |

| Saturn V instrument unit | 4,600 | 2,100 | — | 3.0 | 0.91 | 21.6 | 6.6 |  | |

| Orbital Workshop | 78,000 | 35,000[4] | 9,550 | 270[4] | 48.1 | 14.7 | 21.6 | 6.6 | |

| Total in orbit | 168,750 | 76,540 | 12,417 | 351.6 | 82.4 | 25.1 | 21.6 | 6.6 | |

| Apollo CSM | 31,000 | 14,000 | 210 | 5.9 | 36.1 | 11.0 | 12.8 | 3.9 |  |

| Total with CSM | 199,750 | 90,610[4] | 12,627 | 357.6 | 118.5 | 36.1 | 21.6 | 6.6 | |

Operations

For the final two crewed missions to Skylab, NASA assembled a backup Apollo CSM/Saturn IB in case an in-orbit rescue mission was needed, but this vehicle was never flown. The station was damaged during launch when the micrometeoroid shield tore away from the workshop, taking one of the main solar panel arrays with it and jamming the other main array. This deprived Skylab of most of its electrical power and also removed protection from intense solar heating, threatening to make it unusable. The first crew deployed a replacement heat shade and freed the jammed solar panels to save Skylab. This was the first time that a repair of this magnitude was performed in space.

The Apollo Telescope significantly advanced solar science, and observation of the Sun was unprecedented. Astronauts took thousands of photographs of Earth, and the Earth Resources Experiment Package (EREP) viewed Earth with sensors that recorded data in the visible, infrared, and microwave spectral regions. The record for human time spent in orbit was extended beyond the 23 days set by the Soyuz 11 crew aboard Salyut 1 to 84 days by the Skylab 4 crew.

Later plans to reuse Skylab were stymied by delays in the development of the Space Shuttle, and Skylab's decaying orbit could not be stopped. Skylab's atmospheric reentry began on July 11, 1979,[7] amid worldwide media attention. Before re-entry, NASA ground controllers tried to adjust Skylab's orbit to minimize the risk of debris landing in populated areas,[8] targeting the south Indian Ocean, which was partially successful. Debris showered Western Australia, and recovered pieces indicated that the station had disintegrated lower than expected.[9] As the Skylab program drew to a close, NASA's focus had shifted to the development of the Space Shuttle. NASA space station and laboratory projects included Spacelab, Shuttle-Mir, and Space Station Freedom, which was merged into the International Space Station.

Background

Rocket engineer Wernher von Braun, science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke, and other early advocates of crewed space travel, expected until the 1960s that a space station would be an important early step in space exploration. Von Braun participated in the publishing of a series of influential articles in Collier's magazine from 1952 to 1954, titled "Man Will Conquer Space Soon!". He envisioned a large, circular station 250 feet (75 m) in diameter that would rotate to generate artificial gravity and require a fleet of 7,000 short tons (6,400 metric tons) space shuttles for construction in orbit. The 80 men aboard the station would include astronomers operating a telescope, meteorologists to forecast the weather, and soldiers to conduct surveillance. Von Braun expected that future expeditions to the Moon and Mars would leave from the station.[10]

The development of the transistor, the solar cell, and telemetry, led in the 1950s and early 1960s to uncrewed satellites that could take photographs of weather patterns or enemy nuclear weapons and send them to Earth. A large station was no longer necessary for such purposes, and the United States Apollo program to send men to the Moon chose a mission mode that would not need in-orbit assembly. A smaller station that a single rocket could launch retained value, however, for scientific purposes.[11]

Early studies

In 1959, von Braun, head of the Development Operations Division at the Army Ballistic Missile Agency, submitted his final Project Horizon plans to the U.S. Army. The overall goal of Horizon was to place men on the Moon, a mission that would soon be taken over by the rapidly forming NASA. Although concentrating on the Moon missions, von Braun also detailed an orbiting laboratory built out of a Horizon upper stage,[12] an idea used for Skylab.[13] A number of NASA centers studied various space station designs in the early 1960s. Studies generally looked at platforms launched by the Saturn V, followed up by crews launched on Saturn IB using an Apollo command and service module,[14] or a Gemini capsule[15] on a Titan II-C, the latter being much less expensive in the case where cargo was not needed. Proposals ranged from an Apollo-based station with two to three men, or a small "canister" for four men with Gemini capsules resupplying it, to a large, rotating station with 24 men and an operating lifetime of about five years.[16] A proposal to study the use of a Saturn S-IVB as a crewed space laboratory was documented in 1962 by the Douglas Aircraft Company.[17]

Air Force plans

The Department of Defense (DoD) and NASA cooperated closely in many areas of space.[18] In September 1963, NASA and the DoD agreed to cooperate in building a space station.[19] The DoD wanted its own crewed facility, however,[20] and in December 1963 it announced Manned Orbital Laboratory (MOL), a small space station primarily intended for photo reconnaissance using large telescopes directed by a two-person crew. The station was the same diameter as a Titan II upper stage, and would be launched with the crew riding atop in a modified Gemini capsule with a hatch cut into the heat shield on the bottom of the capsule.[21][22] MOL competed for funding with a NASA station for the next five years[23] and politicians and other officials often suggested that NASA participate in MOL or use the DoD design.[20] The military project led to changes to the NASA plans so that they would resemble MOL less.[19]

Development

Apollo Applications Program

NASA management was concerned about losing the 400,000 workers involved in Apollo after landing on the Moon in 1969.[24] A reason von Braun, head of NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center during the 1960s, advocated a smaller station after his large one was not built was that he wished to provide his employees with work beyond developing the Saturn rockets, which would be completed relatively early during Project Apollo.[25] NASA set up the Apollo Logistic Support System Office, originally intended to study various ways to modify the Apollo hardware for scientific missions. The office initially proposed a number of projects for direct scientific study, including an extended-stay lunar mission which required two Saturn V launchers, a "lunar truck" based on the Lunar Module (LM), a large, crewed solar telescope using an LM as its crew quarters, and small space stations using a variety of LM or CSM-based hardware. Although it did not look at the space station specifically, over the next two years the office would become increasingly dedicated to this role. In August 1965, the office was renamed, becoming the Apollo Applications Program (AAP).[26]

As part of their general work, in August 1964 the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC) presented studies on an expendable lab known as Apollo X, short for Apollo Extension System. Apollo X would have replaced the LM carried on the top of the S-IVB stage with a small space station slightly larger than the CSM's service area, containing supplies and experiments for missions between 15 and 45 days' duration. Using this study as a baseline, a number of different mission profiles were looked at over the next six months.

Wet workshop

In November 1964, von Braun proposed a more ambitious plan to build a much larger station built from the S-II second stage of a Saturn V. His design replaced the S-IVB third stage with an aeroshell, primarily as an adapter for the CSM on top. Inside the shell was a 10 feet (3.0 m) cylindrical equipment section. On reaching orbit, the S-II second stage would be vented to remove any remaining hydrogen fuel, then the equipment section would be slid into it via a large inspection hatch. This became known as a "wet workshop" concept, because of the conversion of an active fuel tank. The station filled the entire interior of the S-II stage's hydrogen tank, with the equipment section forming a "spine" and living quarters located between it and the walls of the booster. This would have resulted in a very large 33 by 45 feet (10 by 14 m) living area. Power was to be provided by solar cells lining the outside of the S-II stage.[27]

One problem with this proposal was that it required a dedicated Saturn V launch to fly the station. At the time the design was being proposed, it was not known how many of the then-contracted Saturn Vs would be required to achieve a successful Moon landing. However, several planned Earth-orbit test missions for the LM and CSM had been canceled, leaving a number of Saturn IBs free for use. Further work led to the idea of building a smaller "wet workshop" based on the S-IVB, launched as the second stage of a Saturn IB.

A number of S-IVB-based stations were studied at MSC from mid-1965, which had much in common with the Skylab design that eventually flew. An airlock would be attached to the hydrogen tank, in the area designed to hold the LM, and a minimum amount of equipment would be installed in the tank itself in order to avoid taking up too much fuel volume. Floors of the station would be made from an open metal framework that allowed the fuel to flow through it. After launch, a follow-up mission launched by a Saturn IB would launch additional equipment, including solar panels, an equipment section and docking adapter, and various experiments. Douglas Aircraft Company, builder of the S-IVB stage, was asked to prepare proposals along these lines. The company had for several years been proposing stations based on the S-IV stage, before it was replaced by the S-IVB.[28]

On April 1, 1966, MSC sent out contracts to Douglas, Grumman, and McDonnell for the conversion of an S-IVB spent stage, under the name Saturn S-IVB spent-stage experiment support module (SSESM).[29] In May 1966, astronauts voiced concerns over the purging of the stage's hydrogen tank in space. Nevertheless, in late July 1966, it was announced that the Orbital Workshop would be launched as a part of Apollo mission AS-209, originally one of the Earth-orbit CSM test launches, followed by two Saturn I/CSM crew launches, AAP-1 and AAP-2.

The Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL) remained AAP's chief competitor for funds, although the two programs cooperated on technology. NASA considered flying experiments on MOL or using its Titan IIIC booster instead of the much more expensive Saturn IB. The agency decided that the Air Force station was not large enough and that converting Apollo hardware for use with Titan would be too slow and too expensive.[30] The DoD later canceled MOL in June 1969.[31]

Dry workshop

Design work continued over the next two years, in an era of shrinking budgets.[32] (NASA sought US$450 million for Apollo Applications in fiscal year 1967, for example, but received US$42 million.)[33] In August 1967, the agency announced that the lunar mapping and base construction missions examined by the AAP were being canceled. Only the Earth-orbiting missions remained, namely the Orbital Workshop and Apollo Telescope Mount solar observatory. The success of Apollo 8 in December 1968, launched on the third flight of a Saturn V, made it likely that one would be available to launch a dry workshop.[34] Later, several Moon missions were canceled as well, originally to be Apollo missions 18 through 20. The cancellation of these missions freed up three Saturn V boosters for the AAP program. Although this would have allowed them to develop von Braun's original S-II-based mission, by this time so much work had been done on the S-IV-based design that work continued on this baseline. With the extra power available, the wet workshop was no longer needed;[35] the S-IC and S-II lower stages could launch a "dry workshop", with its interior already prepared, directly into orbit.

Habitability

A dry workshop simplified plans for the interior of the station.[36] Industrial design firm Raymond Loewy/William Snaith recommended emphasizing habitability and comfort for the astronauts by providing a wardroom for meals and relaxation[37] and a window to view Earth and space, although astronauts were dubious about the designers' focus on details such as color schemes.[38] Habitability had not previously been an area of concern when building spacecraft due to their small size and brief mission durations, but the Skylab missions would last for months.[39] NASA sent a scientist on Jacques Piccard's Ben Franklin submarine in the Gulf Stream in July and August 1969 to learn how six people would live in an enclosed space for four weeks.[40]

Astronauts were uninterested in watching movies on a proposed entertainment center or in playing games, but they did want books and individual music choices.[38] Food was also important; early Apollo crews complained about its quality, and a NASA volunteer found it intolerable to live on the Apollo food for four days on Earth. Its taste and composition were unpleasant, in the form of cubes and squeeze tubes. Skylab food significantly improved on its predecessors by prioritizing palatability over scientific needs.[41]

For sleeping in space, each astronaut had a private area the size of a small walk-in closet, with a curtain, sleeping bag, and locker.[42] Designers also added a shower[43][44] and a toilet[45][46] for comfort and to obtain precise urine and feces samples for examination on Earth.[47] The waste samples were so important that they would have been priorities in any rescue mission.[48]

Skylab did not have recycling systems such as the conversion of urine to drinking water; it also did not dispose of waste by dumping it into space. The S-IVB's 73,280 liters (16,120 imp gal; 19,360 U.S. gal) liquid oxygen tank below the Orbital Work Shop was used to store trash and wastewater, passed through an airlock.

Operational history

Completion and launch

On August 8, 1969, the McDonnell Douglas Corporation received a contract for the conversion of two existing S-IVB stages to the Orbital Workshop configuration. One of the S-IV test stages was shipped to McDonnell Douglas for the construction of a mock-up in January 1970. The Orbital Workshop was renamed "Skylab" in February 1970 as a result of a NASA contest.[49] The actual stage that flew was the upper stage of the AS-212 rocket (the S-IVB stage, S-IVB 212). The mission computer used aboard Skylab was the IBM System/4Pi TC-1, a relative of the AP-101 Space Shuttle computers. The Saturn V with serial number SA-513, originally produced for the Apollo program – before the cancellation of Apollo 18, 19, and 20 – was repurposed and redesigned to launch Skylab.[50] The Saturn V's third stage was removed and replaced with Skylab, but with the controlling Instrument Unit remaining in its standard position.

Skylab was launched on May 14, 1973, by the modified Saturn V. The launch is sometimes referred to as Skylab 1. Severe damage was sustained during launch and deployment, including the loss of the station's micrometeoroid shield/sun shade and one of its main solar panels. Debris from the lost micrometeoroid shield further complicated matters by becoming tangled in the remaining solar panel, preventing its full deployment and thus leaving the station with a huge power deficit.[51]

Immediately following Skylab's launch, Pad 39A at Kennedy Space Center was deactivated, and construction proceeded to modify it for the Space Shuttle program, originally targeting a maiden launch in March 1979. The crewed missions to Skylab would occur using a Saturn IB rocket from Launch Pad 39B.

Skylab 1 was the last uncrewed launch from LC-39A until February 19, 2017, when SpaceX CRS-10 was launched from there.

Crewed missions

Three crewed missions, designated Skylab 2, Skylab 3, and Skylab 4, were made to Skylab in the Apollo command and service modules. The first crewed mission, Skylab 2, launched on May 25, 1973, atop a Saturn IB and involved extensive repairs to the station. The crew deployed a parasol-like sunshade through a small instrument port from the inside of the station, bringing station temperatures down to acceptable levels and preventing overheating that would have melted the plastic insulation inside the station and released poisonous gases. This solution was designed by Jack Kinzler, who won the NASA Distinguished Service Medal for his efforts. The crew conducted further repairs via two spacewalks (extravehicular activity or EVA). The crew stayed in orbit with Skylab for 28 days. Two additional missions followed, with the launch dates of July 28, 1973, (Skylab 3) and November 16, 1973, (Skylab 4), and mission durations of 59 and 84 days, respectively. The last Skylab crew returned to Earth on February 8, 1974.[52]

In addition to the three crewed missions, there was a rescue mission on standby that had a crew of two, but could take five back down.

- Skylab 2: launched May 25, 1973[53]

- Skylab 3: launched July 28, 1973

- Skylab 4: launched November 16, 1973

- Skylab 5: cancelled

- Skylab Rescue on standby

Also of note was the three-man crew of Skylab Medical Experiment Altitude Test (SMEAT), who spent 56 days in 1972 at low-pressure on Earth to evaluate medical experiment equipment.[54] This was a spaceflight analog test in full gravity, but Skylab hardware was tested and medical knowledge was gained.

Orbital operations

| Mission |

|

|---|---|

| Skylab 2 | |

| Skylab 3 | |

| Skylab 4 |

Originally intended to be visited by one 28–day and two 56–day missions for a total of 140 days,[55] Skylab was ultimately occupied for 171 days and 13 hours during its three crewed expeditions, orbiting the Earth 2,476 times. Each of these extended the human record of 23 days for amount of time spent in space set by the Soviet Soyuz 11 crew aboard the space station Salyut 1 on June 30, 1971. Skylab 2 lasted 28 days, Skylab 3 – 56 days, and Skylab 4 – 84 days. Astronauts performed ten spacewalks, totaling 42 hours and 16 minutes. Skylab logged about 2,000 hours of scientific and medical experiments, 127,000 frames of film of the Sun and 46,000 of Earth.[56] Solar experiments included photographs of eight solar flares and produced valuable results[57] that scientists stated would have been impossible to obtain with uncrewed spacecraft.[58] The existence of the Sun's coronal holes was confirmed because of these efforts.[59] Many of the experiments conducted investigated the astronauts' adaptation to extended periods of microgravity.

A typical day began at 6 a.m. Central Time Zone.[60] Although the toilet was small and noisy, both veteran astronauts – who had endured earlier missions' rudimentary waste-collection systems – and rookies complimented it.[61][44][62] The first crew enjoyed taking a shower once a week, but found drying themselves in weightlessness[62] and vacuuming excess water difficult; later crews usually cleaned themselves daily with wet washcloths instead of using the shower. Astronauts also found that bending over in weightlessness to put on socks or tie shoelaces strained their abdominal muscles.[63]

Breakfast began at 7 a.m. Astronauts usually stood to eat, as sitting in microgravity also strained their abdominal muscles. They reported that their food – although greatly improved from Apollo – was bland and repetitive, and weightlessness caused utensils, food containers, and bits of food to float away; also, gas in their drinking water contributed to flatulence. After breakfast and preparation for lunch, experiments, tests and repairs of spacecraft systems and, if possible, 90 minutes of physical exercise followed; the station had a bicycle and other equipment, and astronauts could jog around the water tank. After dinner, which was scheduled for 6 p.m., crews performed household chores and prepared for the next day's experiments. Following lengthy daily instructions (some of which were up to 15 meters long) sent via teleprinter, the crews were often busy enough to postpone sleep.[64][65] The station offered what a later study called "a highly satisfactory living and working environment for crews", with enough room for personal privacy.[66] Although it had a dart set,[67] playing cards, and other recreational equipment in addition to books and music players, the window with its view of Earth became the most popular way to relax in orbit.[68]

Experiments

Prior to departure about 80 experiments were named, although they are also described as "almost 300 separate investigations".[69]

Experiments were divided into six broad categories:

- Life science – human physiology, biomedical research; circadian rhythms (mice, gnats)

- Solar physics and astronomy – sun observations (eight telescopes and separate instrumentation); Comet Kohoutek (Skylab 4); stellar observations; space physics

- Earth resources – mineral resources; geology; hurricanes; land and vegetation patterns

- Material science – welding, brazing, metal melting; crystal growth; water / fluid dynamics

- Student research – 19 different student proposals. Several experiments were commended by the crew, including a dexterity experiment and a test of web-spinning by spiders in low gravity.

- Other – human adaptability, ability to work, dexterity; habitat design/operations.

Because the solar scientific airlock – one of two research airlocks – was unexpectedly occupied by the "parasol" that replaced the missing meteorite shield, a few experiments were instead installed outside with the telescopes during spacewalks or shifted to the Earth-facing scientific airlock.

Skylab 2 spent less time than planned on most experiments due to station repairs. On the other hand, Skylab 3 and Skylab 4 far exceeded the initial experiment plans, once the crews adjusted to the environment and established comfortable working relationships with ground control.

The figure (below) lists an overview of most major experiments.[70] Skylab 4 carried out several more experiments, such as to observe Comet Kohoutek.[71]

Astronaut maneuvering equipment

As a technology demonstration, the crew practiced flying the Automatically Stabilized Maneuvering Unit (ASMU) inside the spacious dome of the Orbital Workshop. Designed to enable astronauts to perform untethered movements in microgravity.[72] The ASMU tests established key piloting characteristics and capability base for the MMU systems used on the Space Shuttle missions.[73]

Nobel Prize

Riccardo Giacconi shared the 2002 Nobel Prize in Physics for his study of X-ray astronomy, including the study of emissions from the Sun onboard Skylab, contributing to the birth of X-ray astronomy.[74]

Film vaults and window radiation shield

Skylab had certain features to protect vulnerable technology from radiation.[75] The window was vulnerable to darkening, and this darkening could affect experiment S190.[75] As a result, a light shield that could be open or shut was designed and installed on Skylab.[75] To protect a wide variety of films, used for a variety of experiments and for astronaut photography, there were five film vaults.[75] There were four smaller film vaults in the Multiple Docking Adapter, mainly because the structure could not carry enough weight for a single larger film vault.[75] The orbital workshop could handle a single larger safe, which is also more efficient for shielding.[75] A later example of a radiation vault is the Juno Radiation Vault for the Juno Jupiter orbiter, launched in 2011, which was designed to protect much of the uncrewed spacecraft's electronics, using 1 cm thick walls of titanium.[76]

The large vault in the orbital workshop had an empty mass of 2,398 pounds (1,088 kg).[75] The four smaller vaults had combined mass of 1,545 lb (701 kg).[75] The primary construction material of all five safes was aluminum.[75] When Skylab re-entered there was one 180 pounds (82 kg) chunk of aluminum found that was thought to be a door to one of the film vaults.[77] The large film vault was one of the heaviest single pieces of Skylab to re-enter Earth's atmosphere.[78]

The Skylab film vault was used for storing film from various sources including the Apollo Telescope Mount solar instruments.[79] Six ATM experiments used film to record data, and over the course of the missions over 150,000 successful exposures were recorded.[79] The film canister had to be manually retrieved on crewed spacewalks to the instruments during the missions.[79] The film canisters were returned to Earth aboard the Apollo capsules when each mission ended, and were among the heaviest items that had to be returned at the end of each mission.[79] The heaviest canisters weighed 40 kg and could hold up to 16,000 frames of film.[79]

Gyroscopes

There were two types of gyroscopes on Skylab. Control-moment gyroscopes (CMG) could physically move the station, and rate gyroscopes measured the rate of rotation to find its orientation.[80] The CMG helped provide the fine pointing needed by the Apollo Telescope Mount, and to resist various forces that can change the station's orientation.[81]

Some of the forces acting on Skylab that the pointing system needed to resist:[81]

- Gravity gradient

- Aerodynamic disturbance

- Internal movements of crew.

The Skylab-A attitude and pointing control system has been developed to meet the high accuracy requirements established by the desired experiment conditions. Conditions must be maintained by the control system under the influence of external and internal disturbance torques, such as gravity gradient and aerodynamic disturbances and onboard astronaut motion.

— Skylab Attitude and Pointing Control System (NASA Technical Note D-6068)This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.[81]

Skylab was the first large spacecraft to use big gyroscopes, capable of controlling its attitude.[82] The control could also be used to help point the instruments.[82] The gyroscopes took about ten hours to get spun up if they were turned off.[83] There was also a thruster system to control Skylab's attitude.[83] There were 9 rate-gyroscope sensors, 3 for each axis.[83] These were sensors that fed their output to the Skylab digital computer.[83] Two of three were active and their input was averaged, while the third was a backup.[83] From NASA SP-400 Skylab, Our First Space Station, "each Skylab control-moment gyroscope consisted of a motor-driven rotor, electronics assembly, and power inverter assembly. The 21-inch-diameter (530 mm) rotor weighed 155 pounds (70 kg) and rotated at approximately 8950 revolutions per minute".[84]

There were three control moment gyroscopes on Skylab, but only two were required to maintain pointing.[84] The control and sensor gyroscopes were part of a system that help detect and control the orientation of the station in space.[84] Other sensors that helped with this were a Sun tracker and a star tracker.[84] The sensors fed data to the main computer, which could then use the control gyroscopes and or the thruster system to keep Skylab pointed as desired.[84]

Shower

Skylab had a zero-gravity shower system in the work and experiment section of the Orbital Workshop[85] designed and built at the Manned Spaceflight Center.[54] It had a cylindrical curtain that went from floor to ceiling and a vacuum system to suck away water.[86] The floor of the shower had foot restraints.

To bathe, the user coupled a pressurized bottle of warmed water to the shower's plumbing, then stepped inside and secured the curtain. A push-button shower nozzle was connected by a stiff hose to the top of the shower.[54][87] The system was designed for about 6 pints (2.8 liters) of water per shower,[88] the water being drawn from the personal hygiene water tank.[54] The use of both the liquid soap and water was carefully planned out, with enough soap and warm water for one shower per week per person.[85]

The first astronaut to use the space shower was Paul J. Weitz on Skylab 2, the first crewed mission.[85] He said, "It took a fair amount longer to use than you might expect, but you come out smelling good".[85] A Skylab shower took about two and a half hours, including the time to set up the shower and dissipate used water.[89] The procedure for operating the shower was as follows:[87]

- Fill up the pressurized water bottle with hot water and attach it to the ceiling

- Connect the hose and pull up the shower curtain

- Spray down with water

- Apply liquid soap and spray more water to rinse

- Vacuum up all the fluids and stow items.

One of the big concerns with bathing in space was control of droplets of water so that they did not cause an electrical short by floating into the wrong area.[90] The vacuum water system was thus integral to the shower. The vacuum fed to a centrifugal separator, filter, and collection bag to allow the system to vacuum up the fluids.[87] Waste water was injected into a disposal bag which was in turn put in the waste tank.[54] The material for the shower enclosure was fire-proof beta cloth wrapped around hoops of 43 inches (1,100 mm) diameter; the top hoop was connected to the ceiling.[54] The shower could be collapsed to the floor when not in use.[87] Skylab also supplied astronauts with rayon terrycloth towels which had a color-coded stitching for each crew-member.[85] There were 420 towels on board Skylab initially.[85]

A simulated Skylab shower was also used during the 56-day SMEAT simulation; the crew used the shower after exercise and found it a positive experience.[91]

Cameras and film

There was a variety of hand-held and fixed experiments that used various types of film. In addition to the instruments in the ATM solar observatory, 35 and 70 mm film cameras were carried on board. An analog TV camera was carried that recorded video electronically. These electronic signals could be recorded to magnetic tape or be transmitted to Earth by radio signal.

It was determined that film would fog up to due to radiation over the course of the mission.[75] To prevent this, film was stored in vaults.[75]

Personal (hand-held) camera equipment:[92]

- Television camera

- Westinghouse color

- 25–150 mm zoom

- 16 mm film camera (Maurer), called the 16 mm Data Acquisition Camera.[92] The DAC was capable of very low frame rates, such as for engineering data films, and it had independent shutter speeds.[93] It could be powered from a battery or from Skylab itself.[93] It used interchangeable lenses, and various lens and also film types were used during the missions.[93]

- There were different options for frame rates: 2, 4, 6, 12 and 24 frames per second[92]

- Lenses available: 5, 10, 18, 25, 75, and 100 mm

- Films used:

- Ektachrome film

- SO-368 film

- SO-168 film

Film for the DAC was contained in DAC film magazines, which contained up to 140 feet (42.7 m) of film.[94] At 24 frames per second this was enough for 4 minutes of filming, with progressively longer film times with lower frame rates such as 16 minutes at 6 frames per second.[93] The film had to be loaded or unloaded from the DAC in a photographic dark room.[93]

- 35 mm film cameras (Nikon)[92]

- 70 mm film camera (Hasselblad)[92]

- This had an electric data camera system with Reseau plate

- Films included

- 70 mm Ektachrome

- SO-368 film

- Lenses: 70 mm lens, 100 mm lens.[92]

Experiment S190B was the Actron Earth Terrain Camera.[92]

The S190A was the Multispectral Photographic Camera:[92]

- This consisted of six Itek 70 mm boresighted cameras

- Lenses were f/2.8 with a 21.2° field of view.

There was also a Polaroid SX-70 instant camera,[98] and a pair of Leitz Trinovid 10 × 40 binoculars modified for use in space to aid in Earth observations.[92]

The SX-70 was used to take pictures of the Extreme Ultraviolet monitor by Dr. Garriot, as the monitor provided a live video feed of the solar corona in ultraviolet light as observed by Skylab solar observatory instruments located in the Apollo Telescope Mount.[99]

Computers

Skylab was controlled in part by a digital computer system, and one of its main jobs was to control the pointing of the station; pointing was especially important for its solar power collection and observatory functions.[100] The computer consisted of two actual computers, a primary and a secondary. The system ran several thousand words of code, which was also backed up on the Memory Load Unit (MLU).[100] The two computers were linked to each other and various input and output items by the workshop computer interface.[101] Operations could be switched from the primary to the backup, which were the same design, either automatically if errors were detected, by the Skylab crew, or from the ground.[100]

The Skylab computer was a space-hardened and customized version of the TC-1 computer, a version of the IBM System/4 Pi, itself based on the System 360 computer.[100] The TC-1 had a 16,000-word memory based on ferrite memory cores, while the MLU was a read-only tape drive that contained a backup of the main computer programs.[100] The tape drive would take 11 seconds to upload the backup of the software program to a main computer.[102] The TC-1 used 16-bit words and the central processor came from the 4Pi computer.[102] There was a 16k and an 8k version of the software program.[103]

The computer had a mass of 100 pounds (45.4 kg), and consumed about ten percent of the station's electrical power.[100][101]

- Apollo Telescope Mount Digital Computer[102]

- Attitude and Pointing Control System (APCS)[100]

- Memory Load Unit (MLU).[100]

After launch the computer is what the controllers on the ground communicated with to control the station's orientation.[104] When the sun-shield was torn off the ground staff had to balance solar heating with electrical production.[104] On March 6, 1978, the computer system was re-activated by NASA to control the re-entry.[105]

The system had a user interface that consisted of a display, ten buttons, and a three-position switch.[106] Because the numbers were in octal (base-8), it only had numbers zero to seven (8 keys), and the other two keys were enter and clear.[106] The display could show minutes and seconds which would count down to orbital benchmarks, or it could display keystrokes when using the interface.[106] The interface could be used to change the software program.[106] The user interface was called the Digital Address System (DAS) and could send commands to the computer's command system. The command system could also get commands from the ground.[103]

For personal computing needs Skylab crews were equipped with models of the then new hand-held electronic scientific calculator, which was used in place of slide-rules used on prior space missions as the primary personal computer. The model used was the Hewlett Packard HP 35.[107] Some slide rules continued in use aboard Skylab, and a circular slide rule was at the workstation.[108]

Plans for re-use after the last mission

Calculations made during the mission, based on current values for solar activity and expected atmospheric density, gave the workshop just over nine years in orbit. Slowly at first – dropping 30 kilometers by 1980 – and then faster – another 100 kilometers by the end of 1982 – Skylab would come down, and some time around March 1983 it would burn up in the dense atmosphere.[109]

After nearly 172 days, Skylab considerably exceeded its planned 140 day habitation. The station had held up relatively well, but its onboard supplies were low and its systems were beginning to degrade. One of the three control-moment gyroscopes (CMGs) failed 8 days into Skylab 4,[110] and by the end of the mission another was showing signs of impending failure.[111] With just a single CMG Skylab would be unable to control its attitude, and it was not possible to repair or replace one of the broken gyroscopes on-orbit. Virtually all of the prepackaged food launched with the station had been consumed, Skylab 4's mission extension from 56 to 84 days required the crew take an extra 28 days worth of food with them,[112] but there was still enough water to support three men for 60 days, and enough oxygen/nitrogen to support the same for 140 days.[113]

A fourth crewed mission using an Apollo CSM was considered, which would have used the launch vehicle kept on standby for the Skylab Rescue mission. This would have been a 20-day mission to boost Skylab to a higher altitude and do more scientific experiments.[114] Another plan was to use a Teleoperator Retrieval System (TRS) launched aboard the Space Shuttle (then under development), to robotically re-boost the orbit. When Skylab 5 was cancelled, it was expected Skylab would stay in orbit until the 1980s, which was enough time to overlap with the beginning of Shuttle launches. Other options for launching TRS included the Titan III and Atlas-Agena. No option received the level of effort and funding needed for execution before Skylab's sooner-than-expected re-entry.[115]

The Skylab 4 crew left a bag filled with supplies to welcome visitors, and left the hatch unlocked.[115] Skylab's internal systems were evaluated and tested from the ground, and effort was put into plans for re-using it, as late as 1978.[116] NASA discouraged any discussion of additional visits due to the station's age,[117] but in 1977 and 1978, when the agency still believed the Space Shuttle would be ready by 1979, it completed two studies on reusing the station.[115][118] By September 1978, the agency believed Skylab was safe for crews, with all major systems intact and operational.[119] It still had 180 man-days of water and 420-man-days of oxygen, and astronauts could refill both;[115] the station could hold up to about 600 to 700 man-days of drinkable water and 420 man-days of food.[120] Before Skylab 4 left they did one more boost, running the Skylab thrusters for 3 minutes which added 11 km in height to its orbit. Skylab was left in a 433 by 455 km orbit on departure. At this time, the NASA-accepted estimate for its re-entry was nine years.[109]

The studies cited several benefits from reusing Skylab, which one called a resource worth "hundreds of millions of dollars"[121] with "unique habitability provisions for long duration space flight".[122] Because no more operational Saturn V rockets were available after the Apollo program, four to five shuttle flights and extensive space architecture would have been needed to build another station as large as Skylab's 12,400 cubic feet (350 m3) volume.[123] Its ample size – much greater than that of the shuttle alone, or even the shuttle plus Spacelab[124] – was enough, with some modifications, for up to seven astronauts[125] of both sexes,[126] and experiments needing a long duration in space;[121] even a movie projector for recreation was possible.[122]

Proponents of Skylab's reuse also said repairing and upgrading Skylab would provide information on the results of long-duration exposure to space for future stations.[115] The most serious issue for reactivation was attitude control, as one of the station's gyroscopes had failed[109] and the attitude control system needed refueling; these issues would need EVA to fix or replace. The station had not been designed for extensive resupply. However, although it was originally planned that Skylab crews would only perform limited maintenance,[127] they successfully made major repairs during EVA, such as the Skylab 2 crew's deployment of the solar panel[128] and the Skylab 4 crew's repair of the primary coolant loop.[129][130][131] The Skylab 2 crew fixed one item during EVA by, reportedly, "hit[ting] it with [a] hammer".[132]

Some studies also said, beyond the opportunity for space construction and maintenance experience, reactivating the station would free up shuttle flights for other uses,[121] and reduce the need to modify the shuttle for long-duration missions.[133] Even if the station were not crewed again, went one argument, it might serve as an experimental platform.[134]

Shuttle mission plans

The reactivation would likely have occurred in four phases:[115][135]

- An early Space Shuttle flight would have boosted Skylab to a higher orbit, adding five years of operational life. The shuttle might have pushed or towed the station, but attaching a space tug – the Teleoperator Retrieval System (TRS) – to the station would have been more likely, based on astronauts' training for the task. Martin Marietta won the contract for US$26 million to design the apparatus.[136] TRS would contain about three tons of propellant.[137] The remote-controlled booster had TV cameras and was designed for duties such as space construction and servicing and retrieving satellites the shuttle could not reach. After rescuing Skylab, the TRS would have remained in orbit for future use. Alternatively, it could have been used to de-orbit Skylab for a safe, controlled re-entry and destruction.[138]

- In two shuttle flights, Skylab would have been refurbished. In January 1982, the first mission would have attached a docking adapter and conducted repairs. In August 1983, a second crew would have replaced several system components.

- In March 1984, shuttle crews would have attached a solar-powered Power Expansion Package, refurbished scientific equipment, and conducted 30- to 90-day missions using the Apollo Telescope Mount and the Earth resources experiments.

- Over five years, Skylab would have been expanded to accommodate six to eight astronauts, with a new large docking/interface module, additional logistics modules, Spacelab modules and pallets, and an orbital vehicle space dock using the shuttle's external tank.

The first three phases would have required about US$60 million in 1980s dollars, not including launch costs. Other options for launching TRS were Titan III or Atlas-Agena.[115]

After departure

After a boost of 6.8 miles (10.9 km) by Skylab 4's Apollo CSM before its departure in 1974, Skylab was left in a parking orbit of 269 miles (433 km) by 283 miles (455 km)[109] that was expected to last until at least the early 1980s, based on estimates of the 11-year sunspot cycle that began in 1976.[139][140] In 1962, NASA first considered the potential risks of a space station reentry, but decided not to incorporate a retrorocket system in Skylab due to cost and acceptable risk.[141]

The spent 49-ton Saturn V S-II stage which had launched Skylab in 1973 remained in orbit for almost two years, and made a controlled reentry on January 11, 1975.[142] The re-entry was mistimed however and deorbited slightly earlier in the orbit than planned.[143]

Solar activity

British mathematician Desmond King-Hele of the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) predicted in 1973 that Skylab would de-orbit and crash to Earth in 1979, sooner than NASA's forecast, because of increased solar activity.[140] Greater-than-expected solar activity[145] heated the outer layers of Earth's atmosphere and increased drag on Skylab. By late 1977, NORAD also forecast a reentry in mid-1979;[139] a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) scientist criticized NASA for using an inaccurate model for the second most-intense sunspot cycle in a century, and for ignoring NOAA predictions published in 1976.[146]

The reentry of the USSR's nuclear powered Cosmos 954 in January 1978, and the resulting radioactive debris fall in northern Canada, drew more attention to Skylab's orbit. Although Skylab did not contain radioactive materials, the State Department warned NASA about the potential diplomatic repercussions of station debris.[147] Battelle Memorial Institute forecast that up to 25 tons of metal debris could land in 500 pieces over an area 4,000 miles (6,400 km) long and 1,000 miles (1,600 km) wide. The lead-lined film vault, for example, might land intact at 400 feet per second (120 m/s).[9]

Ground controllers re-established contact with Skylab in March 1978[148] and recharged its batteries.[8] Although NASA worked on plans to reboost Skylab with the Space Shuttle through 1978 and the TRS was almost complete, the agency gave up in December 1978 when it became clear that the shuttle would not be ready in time;[136][149] its first flight, STS-1, did not occur until April 1981. Also rejected were proposals to launch the TRS using one or two uncrewed rockets[115] or to attempt to destroy the station with missiles.[9]

Re-entry and debris

Skylab's impending demise in 1979 was an international media event,[150] with T-shirts and hats with bullseyes[9] and "Skylab Repellent" with a money-back guarantee,[151] wagering on the time and place of re-entry, and nightly news reports. The San Francisco Examiner offered a US$10,000 prize for the first piece of Skylab delivered to its offices; the rival San Francisco Chronicle offered US$200,000 if a subscriber suffered personal or property damage.[8] A Nebraska neighborhood painted a target so that the station would have "something to aim for", a resident said.[151]

The Examiner created the prize to compete with the Chronicle and its popular columnist Herb Caen. Publisher Reg Murphy was reluctant to pay the money, Jeff Jarvis recalled, but NASA assured Jarvis—Caen's counterpart at the Examiner—that the station would not hit land.[152] A report commissioned by NASA calculated that the odds were 1 in 152 of debris hitting any human, and odds of 1 in 7 of debris hitting a city of 100,000 people or more.[153] Special teams were readied to head to any country hit by debris.[8] The event caused so much panic in the Philippines that President Ferdinand Marcos appeared on national television to reassure the public.[140]

A week before re-entry, NASA forecast that it would occur between July 10 and 14, with the 12th the most likely date, and the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) predicted the 14th.[140] In the hours before the event, ground controllers adjusted Skylab's orientation to minimize the risk of re-entry on a populated area.[8] They aimed the station at a spot 810 miles (1,300 km) south-southeast of Cape Town, South Africa, and re-entry began at approximately 16:37 UTC, July 11, 1979.[7] The station did not burn up as fast as NASA expected. Debris landed about 300 miles (480 km) east of Perth, Western Australia due to a four-percent calculation error,[7] and was found between Esperance, Western Australia and Rawlinna, from 31° to 34° S and 122° to 126° E, about 130–150 km (81–93 miles) radius around Balladonia, Western Australia. Residents and an airline pilot saw dozens of colorful flares as large pieces broke up in the atmosphere;[9] the debris landed in an almost unpopulated area, but the sightings still caused NASA to fear human injury or property damage. Don Lind, in a 2005 interview, reports no human injuries or deaths.[154]

Stan Thornton found 24 pieces of Skylab at his home in Esperance. After obtaining his first passport, Thornton flew to San Francisco. After waiting one week for Marshall Space Flight Center to authenticate the wreckage, he collected the Examiner prize and another US$1,000 from a Philadelphia businessman who had flown Thornton's family and girlfriend there.[152][7][9] Analysis of the debris showed that the station had disintegrated 10 miles (16 km) above the Earth, much lower than expected.[9]

The Shire of Esperance light-heartedly fined NASA A$400 for littering.[155] (The fine was written off three months later, but was eventually paid on behalf of NASA in April 2009, after Scott Barley of Highway Radio raised the funds from his morning show listeners.[156][157])

After the demise of Skylab, NASA focused on the reusable Spacelab module, an orbital workshop that could be deployed with the Space Shuttle and returned to Earth. The next American major space station project was Space Station Freedom, which was merged into the International Space Station in 1993 and launched starting in 1998. Shuttle-Mir was another project and led to the US funding Spektr, Priroda, and the Mir Docking Module in the 1990s.

Launchers, rescue, and cancelled missions

Launchers

Launch vehicles:[158]

- SA-513 (Skylab)

- SA-206 (Skylab 2)

- SA-207 (Skylab 3)

- SA-208 (Skylab 4)

- SA-209 (Skylab Rescue and Skylab 5, not launched)

Skylab Revisit

In 1971, before Skylab launched, NASA studied the potential of adding another mission to the three already planned. Called Skylab Revisit, two options were examined. First was an open ended mission that would launch within 30 days after Skylab 4, aiming to last 56 days. The second would visit the station a year after the last crew had left to determine the health and habitability of the station after two years in space.

Neither option was rated highly. The first option's chance of mission success was considered uncertain at best, and the second's even worse given the expected dearth of food, water, and oxygen supplies and the degraded condition of Skylab's system after two years in orbit.[55]

Skylab Rescue

There was a Skylab Rescue mission assembled for the second crewed mission to Skylab, but it was not needed. Another rescue mission was assembled for the last Skylab and was also on standby for ASTP. These missions used a backup Saturn IB rocket (SA-209) and CSM module (CSM-119).

Skylab 5

Skylab 5 would have been a short 20-day mission in April 1974 to conduct more scientific experiments and use the Apollo's Service Propulsion System engine to boost Skylab into a higher orbit, supporting later station use by the Space Shuttle.[159]

Vance Brand (commander), William B. Lenoir (science pilot), and Don Lind (pilot) would have been the crew for this mission, with Brand and Lind being the prime crew for the Skylab Rescue flights.[114] Brand and Lind also trained for a mission that would have aimed Skylab for a controlled deorbit.[154]

Skylab 5 would have used the SA-209 rocket and CMS-119 on standby for Skylab Rescue. Upon its cancellation the rocket was put on display at NASA Kennedy Space Center.[158]

Skylab B

In addition to the flown Skylab space station, a second flight-quality backup Skylab space station had been built during the program. NASA considered using it for a second station in May 1973 or later, to be called Skylab B (S-IVB 515), but decided against it. Launching another Skylab with another Saturn V rocket would have been very costly, and it was decided to spend this money on the development of the Space Shuttle instead.

NASA transferred Skylab B to the National Air and Space Museum in 1975. On display in the museum's Space Hall since 1976, the orbital workshop has been slightly modified to permit viewers to walk through the living quarters.[160][55]

Engineering mock-ups

A full-size 1G training mock-up once used for astronaut training is located at the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center visitor center in Houston, Texas.

Another training mockup, originally used at the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS), is at the U.S. Space & Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama. Originally displayed indoors, it was subsequently stored outdoors for several years to make room for other exhibits. To mark the 40th anniversary of the Skylab program, the Orbital Workshop portion of the trainer was restored and moved into the Davidson Center in 2013.[161][162]

- 1-G trainer at Space Center Houston.

- 1-G trainer at Space Center Houston.

- 1-G trainer at Space Center Houston.

- Trainer at the NBS, before display at the US Space & Rocket Center.

- Astronauts in the NBS deploying the Skylab twin-pole sunshade, 1973.

- Astronauts in the NBS deploying the Skylab protective solar sail, 1973.

- Trainer on display at the US Space & Rocket Center, 1982

- Trainer on display at the US Space & Rocket Center, 2015

- Trainer on display at the US Space & Rocket Center

Mission designations

The numerical identification of the crewed Skylab missions was the cause of some confusion. Originally, the uncrewed launch of Skylab and the three crewed missions to the station were numbered SL-1 through SL-4. During the preparations for the crewed missions, some documentation was created with a different scheme – SLM-1 through SLM-3 – for those missions only. William Pogue credits Pete Conrad with asking the Skylab program director which scheme should be used for the mission patches, and the astronauts were told to use 1–2–3, not 2–3–4. By the time NASA administrators tried to reverse this decision, it was too late, as all the in-flight clothing had already been manufactured and shipped with the 1–2–3 mission patches.[163]

| Mission | Emblem | Commander | Science Pilot | Pilot | Launch date | Landing date | Duration (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skylab 1 SL-1 |  |

uncrewed launch of space station | 1973-05-14 17:30:00 UTC |

1979-07-11 16:37:00 UTC |

2248.96 | ||

| Skylab 2 SL-2 (SLM-1) |  |

Pete Conrad | Joseph Kerwin | Paul Weitz | 1973-05-25 13:00:00 UTC |

1973-06-22 13:49:48 UTC |

28.03 |

| Skylab 3 SL-3 (SLM-2) |  |

Alan Bean | Owen Garriott | Jack Lousma | 1973-07-28 11:10:50 UTC |

1973-09-25 22:19:51 UTC |

59.46 |

| Skylab 4 SL-4 (SLM-3) |  |

Gerald Carr | Edward Gibson | William Pogue | 1973-11-16 14:01:23 UTC |

1974-02-08 15:16:53 UTC |

84.04 |

| Skylab 5 | — | Vance Brand | William B. Lenoir | Don Lind | (April 1974, cancelled) | — | 20 (notional) |

| Skylab Rescue | — | Vance Brand | — | Don Lind | (On Standby) | — | Predicted to last less than 5 days |

L.B. James of NASA Marshall predicted in 1970 that an astronomer, medical doctor, and third scientist might compose each Skylab crew.[164] NASA Astronaut Group 4 and NASA Astronaut Group 6 were scientists recruited as astronauts. They and the scientific community hoped to have two on each Skylab mission, but Deke Slayton, director of flight crew operations, insisted that two trained pilots fly on each.[165] Although the scientists were qualified jet pilots, NASA headquarters made the final decision of one scientist in each Skylab crew on 6 July 1971, after the deaths of three cosmonauts on Soyuz 11.[164]

Kerwin was the first Skylab scientist-astronaut. NASA chose a medical doctor to better understand the effect of spaceflight on the human body on a long-duration mission. Astronauts trained for minor medical procedures at a Houston hospital emergency department.[164]

SMEAT

The Skylab Medical Experiment Altitude Test or SMEAT was a 56-day (8-week) Earth analog Skylab test.[166] The test had a low-pressure high oxygen-percentage atmosphere but it operated under full gravity, as SMEAT was not in orbit. The test had a three-astronaut crew with Commander Robert Crippen, Pilot Karol J. Bobko, and Science Pilot William E. Thornton;[167] there was a focus on medical studies and Thornton was an M.D.[168] The crew lived and worked in the pressure chamber, converted to be like Skylab, from July 26 to September 20, 1972.[54]

| Mission | Emblem | Commander | Pilot | Science Pilot | Start date | End date | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skylab Medical Experiment Altitude Test (SMEAT) | Bob Crippen | Karol Bobko | William Thornton | July 26, 1972 | September 20, 1972[54] | 56 days |

Program cost

From 1966 to 1974, the Skylab program cost a total of US$2.2 billion, (equivalent to $17 billion in 2023). As its three three-person crews spent 510 total man-days in space, each man-day cost approximately US$20 million, compared to US$7.5 million for the International Space Station.[169]

Depictions in film

A minor storyline of the 1986 film Dogs in Space is an attempt by characters of the Melbourne household to fabricate pieces of Skylab and win a radio station's competition to locate debris from the space station as it fell to earth in Australia.

The documentary Searching for Skylab was released online in March 2019. It was written and directed by Dwight Steven-Boniecki and was partly crowdfunded.[170]

The alternate history Apple TV+ original series For All Mankind (2019) depicts the use of the space station in the first episode of the second season, surviving to the 1980s and coexisting with the Space Shuttle program in the alternate timeline.[171]

In the 2011 film Skylab, a family gathers in France and waits for the station to fall out of orbit. It was directed by Julie Delpy.[172]

The 2021 Indian film Skylab depicts fictitious incidents in a Telangana village preceding the disintegration of the space station.[173]

The 2024 series Last Days of the Space Age is set in 1979 Western Australia, during Skylab's reentry near Perth.[174]

- The waste disposal equipment in the backup Skylab at the National Air and Space Museum.

- A mannequin in the backup Skylab at the Smithsonian Institution National Air and Space Museum.

- Skylab commemorative stamp, issue of 1974. The commemorative stamp reflects initial repairs to the station, including the parasol sunshade.

- Illustration of Skylab configuration with docked command and service module

- Vanguard (T-AGM-19) seen as a NASA Skylab tracking ship. Note the tracking radar and telemetry antennas.

- Robbins medallions issued for Skylab missions.

- Space Center Houston Skylab 1-G Trainer mannequin.

See also

- Timeline of longest spaceflights

- Skylab II (proposed space station)

- "Spacelab", a 1978 song by Kraftwerk

- Solar panels on spacecraft

References

Footnotes

- ^ Belew, L. F.; Stuhlinger, E. (January 1973). "EP-107 Skylab: A Guidebook". NASA. Retrieved February 28, 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Belew (1977), p. 18

- ^ Belew (1977), p. 15

- ^ a b c d e Belew, L. F.; Stuhlinger, E. (January 1973). "EP-107 Skylab: A Guidebook. Chapter IV: Skylab Design and Operation". NASA History. Retrieved May 29, 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b "SATURN V LAUNCH VEHICLE FLIGHT EVALUATION REPORT SA-513 SKYLAB 1" (PDF). NASA. 1973. Retrieved May 29, 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Bono, Phillip; Gatland, Kenneth (1976). Frontiers of Space (1st American Revised ed.). MacMillan. p. 121.

- ^ a b c d Benson & Compton (1983), p. 371.

- ^ a b c d e "Skylab's Fiery Fall". Time. July 16, 1979. p. 20. Archived from the original on February 13, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lewis, Richard S. (1984). The Voyages of Columbia: The First True Spaceship. Columbia University Press. pp. 80–82. ISBN 0-231-05924-8 – via Google Books.

- ^ Heppenheimer (1999), pp. 2–5.

- ^ Heppenheimer (1999), pp. 55–60.

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), p. 23.

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), p. 9.

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), p. 10.

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), p. 14.

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), pp. 13–14.

- ^ MSFC Skylab Orbital Workshop Vol. 1. May 1974. p. 21-1. OCLC 840704188.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Heppenheimer (1999), pp. 198–202.

- ^ a b Benson & Compton (1983), p. 17.

- ^ a b Heppenheimer (1999), p. 203.

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), pp. 17–19.

- ^ "MOL (Manned Orbiting Laboratory)". Archived from the original on July 21, 2009.

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), p. 15.

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), pp. 20, 22.

- ^ Heppenheimer (1999), p. 61.

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), p. 20.

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), p. 22.

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), p. 25.

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), p. 30.

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), pp. 45–48.

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), p. 109.

- ^ "Space Hut Workshop Planned". The Mid-Cities Daily News. UPI. January 27, 1967. p. 8 – via Google News.

- ^ Heppenheimer (1999), pp. 64–65.

- ^ Heppenheimer (1999), p. 66.

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), pp. 109–110.

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), p. 130.

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), pp. 133–134.

- ^ a b Benson & Compton (1983), p. 137.

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), p. 133.

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), pp. 139–140.

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), pp. 141–142.

- ^ Belew (1977), p. 82.

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), p. 139.

- ^ a b Belew (1977), p. 80.

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), pp. 152–158.

- ^ Belew (1977), p. 30.

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), p. 165.

- ^ Evans, Ben (August 12, 2012). "Launch Minus Nine Days: The Space Rescue That Never Was". AmericaSpace. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), p. 115.

- ^ Tate, Kara (May 12, 2013). "Skylab: How NASA's First Space Station Worked". Space.com (Infographic). Retrieved April 24, 2014.

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), pp. 253–255.

- ^ "Apollo 201, 202, 4 – 17 / Skylab 2, 3, 4 / ASTP (CSM)".

- ^ "SL-2 (Skylab 1)". heroicrelics.org. Naval Aviation Museum. Retrieved February 19, 2023.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "part3b". history.nasa.gov. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c Frieling, Thomas. "Skylab B:Unflowm Missions, Lost Opportunities". QUEST. 5 (4): 12–21.

Three crews, launched atop Saturn 1Bs, would visit the space station for visits of 28 days for the first crew and 56 days each for the final two crews.

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), p. 340.

- ^ Belew (1977), p. 155.

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), pp. 342–344.

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), p. 357.

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), pp. 307–308.

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), pp. 165, 307.

- ^ a b "Living It Up in Space". Time. June 25, 1973. p. 61. Archived from the original on January 4, 2013.

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), pp. 306–308.

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), pp. 309, 334.

- ^ Martin Marietta & Bendix (1978), pp. 2–7.

- ^ Martin Marietta & Bendix (1978), pp. 2–4.

- ^ "Darts Game, Skylab". Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Archived from the original on April 9, 2010. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Belew (1977), pp. 79–80, 134–135.

- ^ Belew, Leland F.; Stuhlinger, Ernst (1973). "Research Programs on Skylab". SKYLAB: A Guidebook. NASA. p. 114. Retrieved July 10, 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Skylab Experiments". Marshall Space Flight Center, NASA. 1973. Archived from the original on October 23, 2014.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Skylab 4 Command Module". Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Archived from the original on May 19, 2018. Retrieved May 18, 2018.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "50 Years Ago: Second Skylab Crew Begins Record-Breaking Mission - NASA". July 31, 2023. Retrieved December 10, 2024.

- ^ Whitsett, C. E. (October 1, 1986). Role of the Manned Maneuvering Unit for the Space Station (Report). Warrendale, PA: SAE Technical Paper.

- ^ "2002 Nobel Prize for physics to the discoverer of X-ray celestial sources". XMM-Newton – Cosmos. European Space Agency. Retrieved July 22, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k John E. Braly; Thomas R. Heaton (1972). "Radiation Problems Associated with Skylab". Proceedings of the National Symposium on Natural and Manmade Radiation in Space. NASA. "PDF" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 8, 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "NASA – Juno Armored Up to Go to Jupiter". nasa.gov. Archived from the original on January 7, 2017. Retrieved January 6, 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Shayler, David (May 28, 2001). Skylab: America's Space Station. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 313. ISBN 9781852334079.

- ^ O'Toole, Thomas (July 11, 1979). "Latest Forecast Puts Skylab Over Southern Canada". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved January 8, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e "4: The Solar Telescopes on Skylab". SP-402 A New Sun: The Solar Results from Skylab. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Skylab's Gyroscope Has Worst Seizure; Breakdown Feared". The New York Times. January 23, 1974. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ a b c Chzlbb, W. B.; Seltzer, S. M. (February 1, 1971). SKYLAB ATTITUDE AND POINTING CONTROL SYSTEM (Report). NASA. NASA-TN-D-6068. "PDF" (PDF).

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b "p46".

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c d e "ch3".

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c d e "Chapter 3, We Can Fix Anything". NASA.gov.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c d e f "ch5". history.nasa.gov. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Space History Photo: Showering on Skylab". Space.com. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Häuplik-Meusburger, Sandra (October 18, 2011). Architecture for Astronauts: An Activity-based Approach. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9783709106679.

- ^ Clarity, James F.; Weaver, Warren Jr. (November 26, 1984). "BRIEFING; Bathing in Space". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ Guastello, Stephen J. (December 19, 2013). Human Factors Engineering and Ergonomics: A Systems Approach, Second Edition. CRC Press. p. 413. ISBN 9781466560093.

- ^ "Space Station | The Station | Living in Space". www.pbs.org. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ Shayler, David (May 28, 2001). Skylab: America's Space Station. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 157. ISBN 9781852334079.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Belew, L. F.; Stuhlinger, E. (January 1973). "ch5b". history.nasa.gov. Retrieved January 14, 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c d e Handbook of Pilot Operational Equipment for Manned Spaceflight (Report). p. 2.1-1 – via Scribd.

- ^ Handbook of Pilot Operational Equipment for Manned Spaceflight (Report). p. 2.2-1 – via Scribd.

- ^ "OBSERVATION OF THE EARTH ORBITAL AND SUORBITAL SPACEFLIGHT MISSIONS".

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b "Nikon – Imaging Products – Legendary Nikons / Vol. 12. Special titanium Nikon cameras and NASA cameras".

- ^ "OBSERVATION OF THE EARTH ORBITAL AND SUORBITAL SPACEFLIGHT MISSIONS". eol.jsc.nasa.gov. Retrieved January 14, 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Hunt, Curtis "'Quiet' Sun not so Quiet" (September 17, 1973) NASA JSC News Release Archived December 12, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "SL3-135P-3371". NASA. August 15, 1973. Archived from the original on May 8, 2015.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Jenkins, Dennis. "Advanced Vehicle Automation and Computers Aboard the Shuttle". history.nasa.gov. NASA Printing and Design. Retrieved December 31, 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b "IBM and Skylab". IBM Archives. IBM. January 23, 2003. Archived from the original on January 19, 2005. Retrieved December 31, 2017.

- ^ a b c Tomayko, James E. (March 1988). "Chapter Three – The Skylab Computer System – Hardware". Computers in Spaceflight: The NASA Experience. Retrieved December 31, 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b Tomayko, James E. (March 1988). "Chapter Three – The Skylab Computer System – Software". Computers in Spaceflight: The NASA Experience. Retrieved December 31, 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b Tomayko, James E. (March 1988). "Chapter Three – The Skylab Computer System". Computers in Spaceflight: The NASA Experience. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Tomayko, James E. (March 1988). "Chapter Three – The Skylab Computer System – The Reactivation Mission". Computers in Spaceflight: The NASA Experience. Retrieved December 31, 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c d Tomayko, James E. (March 1988). "Chapter Three – The Skylab Computer System – User Interfaces". Computers in Spaceflight: The NASA Experience. Retrieved December 31, 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Calculator, Pocket, Electronic, HP-35". National Air and Space Museum. March 14, 2016. Archived from the original on November 18, 2017. Retrieved November 17, 2017. (no picture)

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Aerospace Related Slide Rules". sliderulemuseum.com. International Slide Rule Museum. Retrieved December 31, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Benson & Compton (1983), p. 361.

- ^ "A Skylab Gyroscope Fails, Leaving Only 2 for Control". The New York Times. November 24, 1973.

- ^ Portree, David (November 14, 2015). "Reviving & Reusing Skylab in the Shuttle Era: NASA Marshall's November 1977 Pitch to NASA Headquarters". No Shortage of Dreams. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

At the time the Skylab 4 crew departed, one CMG had already failed and another showed signs of impending failure.

- ^ Kilka, Mary; Smith, Malcolm (April 1982). Food for U.S. Manned Space Flight (PDF). p. 24.

The Skylab 3 crew launched with a 28-day supply of formulated nutrient-defined, high-density food bars which enabled the extension of their flight from the planned 56-day mission to 84 days.

- ^ Portree, David (November 14, 2015). "Reviving & Reusing Skylab in the Shuttle Era: NASA Marshall's November 1977 Pitch to NASA Headquarters". No Shortage of Dreams. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

- ^ a b Wade, Mark. "Skylab 5". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on May 20, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Oberg, James (February–March 1992). "Skylab's Untimely Fate". Air & Space. pp. 73–79. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020.

- ^ Chubb, W. B. (March 1980). Skylab reactivation mission report (PDF) (Report).

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), pp. 335, 361.

- ^ Martin Marietta & Bendix (1978), p. 3-1.

- ^ Martin Marietta & Bendix (1978), p. 3-2.

- ^ Martin Marietta & Bendix (1978), p. 2-7.

- ^ a b c Martin Marietta & Bendix (1978), p. 1-13.

- ^ a b Martin Marietta & Bendix (1978), p. 3-11.

- ^ Martin Marietta & Bendix (1978), pp. 1-12 to 1-13.

- ^ Martin Marietta & Bendix (1978), p. 2-8.

- ^ Martin Marietta & Bendix (1978), p. 2-31.

- ^ Martin Marietta & Bendix (1978), p. 3-14.

- ^ Belew (1977), p. 34.

- ^ Belew (1977), pp. 73–75.

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), p. 317.

- ^ Belew (1977), p. 130.

- ^ Martin Marietta & Bendix (1978), p. 3-21.

- ^ Belew (1977), p. 89.

- ^ Martin Marietta & Bendix (1978), pp. 2–9, 10.