Sino-Tibetan War of 1930–1932

| Sino-Tibetan War of 1930–1932 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

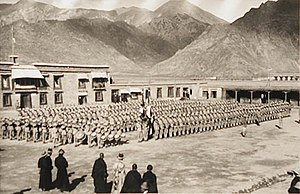

Tibetan Army troops in 1933 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Several thousand Hui Muslim and Han Chinese soldiers | unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| unknown | unknown | ||||||

The Sino-Tibetan War of 1930–1932[1] (Chinese: 康藏糾紛; pinyin: Kāngcáng jiūfēn, lit. Kham–Tibet dispute), also known as the Second Sino-Tibetan War,[2] began in May and June 1930 when the Tibetan Army under the 13th Dalai Lama invaded the Chinese-administered eastern Kham region (later called Xikang), and the Yushu region in Qinghai, in a struggle over control and corvée labor in Dajin Monastery. The Tibetan army, with British support, easily defeated the Sichuan army, which was focused on internal fights.[3][4][5] Ma clique warlord Ma Bufang secretly sent a telegram to Sichuan warlord Liu Wenhui and the leader of the Republic of China, Chiang Kai-shek, suggesting a joint attack on the Tibetan forces. The Republic of China then defeated the Tibetan armies and recaptured its lost territory.

Background

The roots of the conflict lay in three areas: first, the disputed border between Tibetan government territory and the territory of the Republic of China, with the Tibetan government in principle claiming areas inhabited by Tibetans in neighboring Chinese provinces (Qinghai, Sichuan) which were in fact ruled by Chinese warlords loosely aligned with the Republic; second, the tense relationship between the 13th Dalai Lama and the 9th Panchen Lama, which led to the latter's exile in Chinese-controlled territory; and third, the complexities of power politics among local Tibetan dignitaries, both religious and secular[6][page needed], like dispute between Yellow and Red sects of Tibetan Buddhism.[7]

The proximate cause was that the chieftain of Beri, an area claimed by Tibet but under Sichuan control, seized the properties of the incarnate lama of Nyarong Monastery, who sought support from nearby Targye Monastery (Chinese: 大金寺). The chieftain of Beri was reportedly incited by supporters of the 9th Panchen Lama. When the Nyarong Lama and monks from Targye Monastery regained control of Nyarong Monastery in June 1930,[8] the chieftain of Beri responded by requesting help from local Chinese warlord Liu Wenhui, the governor of Sichuan. Liu's forces quickly took control of the area. The Targye monks in turn requested the aid of the Tibetan government, whose forces entered Beri and drove Liu Wenhui's army out.[6][page needed]

Conflict

Kuomintang Muslim official Tang Kesan was sent to negotiate for an end to the fighting. Ma Xiao was a Muslim brigade commander in Liu Wenhui's army.[9] Muslim General Ma Fuxiang, as head of the Mongolian and Tibetan Affairs Commission, sent a telegraph to Tang Kesan ordering him to breach the agreement with Tibet, because he was concerned that political rivals in Nanjing were using the incident.[10]

Over the next few years the Tibetans repeatedly attacked Liu Wenhui's forces, but were defeated several times. In 1932 Tibet made the decision to expand the war into Qinghai against Ma Bufang, the reasons for which have speculated upon by many historians.[11]

Qinghai–Tibet War

When the ceasefire negotiated by Tang failed, Tibet expanded the war in 1932, attempting to capture parts of southern Qinghai province following a dispute in Yushu, Qinghai, over a monastery. Ma Bufang saw this as an opportunity to retake Xikang for China.[12] Under Gen. Ma the 9th Division (Kokonor)--composed entirely of Muslim troops—prepared for an offensive against the Tibetans (Kokonor is another name for Qinghai).[13][14] The war against the Tibetan army was led by the Muslim General Ma Biao.[15]

In 1931 Ma Biao became leader of the Yushu Defense Brigade.[16] He was the second brigade commander while the first brigade was led by Ma Xun. Wang Jiamei was his secretary during the war against Tibet.[17] Ma Biao fought to defend Lesser Surmang against the attacking Tibetans on March 24–26, 1932. The invading Tibetan forces massively outnumbered Ma Biao's defending Qinghai forces. Cai Zuozhen, the local Qinghai Tibetan Buddhist Buqing tribal chief,[18] was fighting on the Qinghai side against the invading Tibetans.[19]

Their forces retreated to the capital of Yushu county, Jiegue, under Ma Biao to defend it against the Tibetans while the Republic of China government under Chiang Kai-shek was petitioned for military aid like wireless telegraphs, money, ammunition and rifles.[20]

A wireless telegraph was sent and solved the communication problem. Ma Xun was sent to reinforce the Qinghai forces and accompanied by propagandists, while mobile films and medical treatment provided by doctors awed the primitive Tibetan locals.[21]

Ma Xun reinforced Jiegu after Ma Biao fought for more than 2 months against the Tibetans. The Tibetan army numbered 3,000. Repeated Tibetan attacks were repulsed by Ma Biao—even though his troops were outnumbered—since the Tibetans were poorly prepared for war, and so they suffered heavier casualties than the Qinghai army.[22] Dud cannon rounds were fired by the Tibetans and their artillery was useless. Ma Lu was sent with more reinforcements to assist Ma Biao and Ma Xun along with La Pingfu.[23] Jiegu's siege was relieved by La Pingfu on August 20, 1932, which freed Ma Biao and Ma Xun's soldiers to assault the Tibetans. Hand-to-hand combat with swords ensued as the Tibetan army was slaughtered by the "Great Sword" group of the Qinghai army in a midnight attack led by Ma Biao and Ma Xun. The Tibetans suffered massive casualties and fled the battlefield as they were routed. The land occupied in Yushu by the Tibetans was retaken.[24]

Both the Tibetan army and Ma Biao's soldiers committed war crimes according to Cai. Tibetan soldiers had raped nuns and women (local Qinghai Tibetans) after looting monasteries and destroying villages in Yushu while Tibetan soldiers who were surrendering and fleeing were summarily executed by Ma Biao's soldiers and supplies were seized from the local nomad civilians by Ma Biao's army.[25]

Ma Biao ordered the religious books, items, and statues of the Tibetan Gadan monastery which had started the war, to be destroyed since he was furious at their role in the war. He ordered the burning of the monastery by the Yushu Tibetan Buddhist chief Cai. But Cai could not bring himself to burn the temple and lied to Biao that the temple had been burned it.[26] Ma Biao seized thousands of silver dollars worth of items from local nomads as retribution for them assisting the invading Tibetan army.[27] On August 24 and 27, massive artillery duels occurred in Surmang between the Tibetans and Qinghai army. 200 Tibetans soldiers were killed in battle by the Qinghai army after the Tibetans came to reinforce their positions. Greater Surmang was abandoned by the Tibetans as they came under attack by La Pingfu on September 2. In Batang, La Pingfu, Ma Biao, and Ma Xun met Ma Lu's reinforcements on September 20.[28]

Liu Wenhui, the Xikang warlord, had reached an agreement with Ma Bufang and Ma Lin's Qinghai army to strike the Tibetans in Xikang. A coordinated joint Xikang-Qinghai attack against the Tibetan army at Qingke monastery led to a Tibetan retreat from the monastery and the Jinsha river.[29]

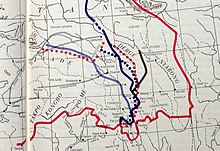

The army of Ma Bufang vanquished the Tibetan armies and recaptured several counties in Xikang province, including Shiqu, Dengke and other counties.[9][30][31] The Tibetans were pushed back to the other side of the Jinsha River.[32][33] The Qinghai army recaptured counties that had fallen into the hands of the Tibetan army since 1919. Ma and Liu warned Tibetan officials not to cross the Jinsha River again.[34] Ma Bufang defeated the Tibetans at Dan Chokorgon. Several Tibetan generals surrendered, and were subsequently demoted by the Dalai Lama.[35] By August, the Tibetans had lost so much territory to Liu Wenhui and Ma Bufang's forces that the Dalai Lama telegraphed the British government of India for assistance. British pressure led Nanjing to declare a ceasefire.[36] Separate truces were signed by Ma and Liu with the Tibetans in 1933, ending the fighting.[37][38][39][40] All Tibetan (Kham) territories east of the Yangtse fell into Chinese hands, with the Upper Yangtse River becoming the border between Chinese and Tibetan controlled areas.[41]

The Chinese government and Ma Bufang accused the British of supplying weapons and arms to the Tibetans throughout the war. There was, in fact, a sound basis for that accusation: despite persistent diplomatic efforts encouraging both parties to refrain from hostilities and make a comprehensive settlement, the British also provided military training and small quantities of arms and ammunition to Tibet during the period.[42]

The reputation of the Muslim forces of Ma Bufang was boosted by the war and victory against the Tibetan army.[43] The stature of Ma Biao rose over his role in the war and later in 1937 his battles against the Japanese propelled him to fame nationwide in China. Chinese control of the border areas of Kham and Yushu was guarded by the Qinghai army. Chinese Muslim-run schools used their victory in the war against Tibet to show how they defended China's territorial integrity, which Japan had begun violating in 1937.[44]

A play was written and presented in 1936 to Qinghai's "Islam Progressive Council schools" by Shao Hongsi on the war against Tibet with the part of Ma Biao appearing in the play where he defeated the Tibetans. The play presented Ma Biao and Ma Bufang as heroes who defended Yushu from being lost to the Tibetans and comparing it to the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, saying the Muslims stopped the same scenario from happening in Yushu.[45] Ma Biao and his fight against the Japanese were hailed at the schools of the Islam Progressive Council of Qinghai. The emphasis on military training in schools and their efforts to defend China were emphasized in Kunlun magazine by Muslims.[46] In 1939 his battles against the Japanese led to recognition across China.[47]

See also

- British expedition to Tibet (1903–1904)

- Batang uprising (1905)

- Chinese expedition to Tibet (1910)

- Qinghai–Tibet War (1932)

- Battle of Chamdo (1950)

References

Citations

- ^ Goldstein, Melvyn C. (June 18, 1991). A History of Modern Tibet, 1913-1951: The Demise of the Lamaist State. University of California Press. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-520-91176-5.

- ^ Jowett, Philip (November 20, 2013). China's Wars: Rousing the Dragon 1894-1949. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-4728-0673-4.

- ^ Wang, Jiawei; Nyima, Gyaincain; 尼玛坚赞 (1997). The Historical Status of China's Tibet. 五洲传播出版社. p. 149. ISBN 978-7-80113-304-5.

- ^ Goldstein, Melvyn C. (June 18, 1991). A History of Modern Tibet, 1913-1951: The Demise of the Lamaist State. University of California Press. pp. 221–222. ISBN 978-0-520-91176-5.

In June 1930, the Nyarong Lama and monks from Targye monastery seized possession of Nyarong monastery. The Beri chief then sought assistance from General Liu, whose troops took control of the area. The Targye monks responded by asking Lhasa to deploy the Tibetan border troops in Kham in their aid. The Tibetan governor-general sent a Tibetan force from Derge that engaged the Chinese and drove them out of Beri and large parts of Kanze District.

- ^ Jowett, Philip (November 20, 2013). China's Wars: Rousing the Dragon 1894-1949. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-4728-0673-4.

Between 1930 and 1932 a second Sino-Tibetan War was fought between the Tibetan Army and the provincial Chinese troops of Szechwan and Chinghai provinces. A Tibetan army invaded Szechwan and a low-level but brutal conflict lasted for almost two years. (...) After the establishment of a regular Tibetan Army in 1913 they received limited British military aid which continued on a small scale into the 1930s.

- ^ a b Goldstein 1989.

- ^ Lamb, Alastair (1989). Tibet, China & India 1914-1950: A History of Imperial Diplomacy. Roxford Books. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-907129-03-5.

There are suggestions, inherently probable, that the majority of the Beri monks (in that they belonged to the Red Sect and not the Yellow Sect of the Dalai Lama) as well as the people of Beri state were strongly opposed to this proposal for the subordination of a Red Sect (Nyingma) institution to one of the Yellow Sect (Gelugpa).

- ^ Lamb, Alastair (1989). Tibet, China & India 1914-1950: A History of Imperial Diplomacy. Roxford Books. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-907129-03-5.

The Dargye monks sought help from the local Tibetan commander who, it later transpired, provided them with arms (probably rifles of British origin). Beri, apparently supported by another monastery in the district, the Sakya establishment of Nyara, appealed to the Chinese who hastened to send up troops from Tachienlu to reinforce the weak garrison at Kongbatsa, their nearest outpost to the scene of the disturbances. The Dargye monks were joined by other Tibetans, either part of the regular army or, more likely, local Kham auxiliaries begin with, the Beri-Chinese forces were greatly outnumbered; and (as had been the case with the Chinese in the 1917-1918 crisis) they were initially obliged to retreat. The Dargye attack on Beri (and observers from the Tachienlu side were unanimous that Dargye was the aggressor, whatever the rights and wrongs behind its action) evidently took place in or before June 1930.

- ^ a b Hanzhang Ya; Ya Hanzhang (1991). The Biographies of the Dalai Lamas. Foreign Languages Press. pp. 352, 355. ISBN 0-8351-2266-2. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- ^ Oriental Society of Australia (2000). The Journal of the Oriental Society of Australia, Volumes 31-34. Oriental Society of Australia. p. 34. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- ^ Alastair Lamb (1989). Tibet, China & India, 1914–1950: A History of Imperial Diplomacy. Roxford Books. p. 221. ISBN 9780907129035. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- ^ Frederick Roelker Wulsin, Joseph Fletcher, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, National Geographic Society (U.S.), Peabody Museum of Salem (1979). Mary Ellen Alonso (ed.). China's inner Asian frontier: photographs of the Wulsin expedition to northwest China in 1923: from the archives of the Peabody Museum, Harvard University, and the National Geographic Society (illustrated ed.). Harvard University Press. p. 49. ISBN 0-674-11968-1. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ The China weekly review, Volume 61. Millard Publishing House. 1932. p. 185. Retrieved June 1, 2011.

- ^ The China Monthly Review, Volume 61. FJ.W. Powell. 1932. p. 185. Retrieved June 1, 2011.

- ^ Joint Centre for Asia Pacific Studies (1998). Historical themes and current change in Central and Inner Asia: papers presented at the Central and Inner Asian Seminar, University of Toronto, April 25-26, 1997. Joint Centre for Asia Pacific Studies. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-895296-34-1.

- ^ Haas 2016, p. 41.

- ^ Haas 2016, p. 75.

- ^ Haas 2016, pp. 48, 63.

- ^ Haas 2016, p. 76.

- ^ Haas 2016, p. 78.

- ^ Haas 2016, p. 79.

- ^ Haas 2016, p. 80.

- ^ Haas 2016, p. 81.

- ^ Haas 2016, p. 82.

- ^ Haas 2016, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Haas 2016, p. 86.

- ^ Haas 2016, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Haas 2016, p. 88.

- ^ Haas 2016, p. 89.

- ^ Jiawei Wang, Nimajianzan (1997). The Historical Status of China's Tibet. 五洲传播出版社. p. 150. ISBN 7-80113-304-8. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- ^ B. R. Deepak (2005). India & China, 1904-2004: a Century of Peace and Conflict. Manak Publications. p. 82. ISBN 81-7827-112-5. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- ^ International Association for Tibetan Studies. Seminar, Lawrence Epstein (2002). Khams pa Jistories: Visions of People, Place and Authority: PIATS 2000, Tibetan Studies, Proceedings of the 9th Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies, Leiden 2000. BRILL. p. 66. ISBN 90-04-12423-3. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- ^ Gray Tuttle (2005). Tibetan Buddhists in the Making of modern China. Columbia University Press. p. 172. ISBN 0-231-13446-0. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- ^ Xiaoyuan Liu (2004). Frontier Passages: Ethnopolitics and the Rise of Chinese Communism, 1921–1945. Stanford University Press. p. 89. ISBN 0-8047-4960-4. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- ^ K. Dhondup (1986). The Water-Bird and Other Years: A History of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama and After. Rangwang Publishers. p. 60. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- ^ Richardson, Hugh E. (1984). Tibet and Its History. 2nd Edition, pp. 134-136. Shambhala Publications, Boston. ISBN 0-87773-376-7 (pbk).

- ^ Oriental Society of Australia (2000). The Journal of the Oriental Society of Australia, Volumes 31-34. Oriental Society of Australia. pp. 35, 37. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- ^ Michael Gervers, Wayne Schlepp, Joint Centre for Asia Pacific Studies (1998). Historical Themes and Current Change in Central and Inner Asia: Papers Presented at the Central and Inner Asian Seminar, University of Toronto, April 25–26, 1997, Volume 1997. Joint Centre for Asia Pacific Studies. pp. 73, 74, 76. ISBN 1-895296-34-X. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wars and Conflicts Between Tibet and China

- ^ Andreas Gruschke (2004). The Cultural Monuments of Tibet's Outer Provinces: The Qinghai Part of Kham. White Lotus Press. p. 32. ISBN 974-480-061-5. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- ^ Goldstein, M.C. (1994). "Change, Conflict and Continuity among a community of nomadic pastoralists—A Case Study from western Tibet, 1950–1990". In Barnett, Robert; Akiner, Shirin (eds.). Resistance and Reform in Tibet. London: Hurst & Co. Retrieved April 24, 2014.

- ^ Richardson, Hugh E. (1984) [1962]. Tibet & Its History (Second, Revised and Updated ed.). Shambhala. p. 116 to 124, 134 to 138, 146 and 147, 178 and 179. ISBN 0-87773-292-2.

- ^ Haas 2016, p. 91.

- ^ Haas 2016, p. 92.

- ^ Haas 2016, pp. 259–261.

- ^ Haas 2016, p. 298.

- ^ Haas 2016, p. 304.

Sources

- Goldstein, Melvyn C. (1989), A History of Modern Tibet, 1913-1951: The Demise of the Lamaist State, Gelek Rimpoche, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-91176-5

- Haas, William Brent (2016). Qinghai Across Frontiers: State- and Nation-Building under the Ma Family, 1911–1949 (PDF) (PhD thesis). University of California, San Diego.

- Lamb, Alastair (1989), Tibet, China & India, 1914-1950: a history of imperial diplomacy, Roxford Books, ISBN 9780907129035

- Lin, Hsiao-ting (October 2006), "Making Known the Unknown World: Ethnicity, Religion and Political Manipulations in 1930s Southwest China", American Journal of Chinese Studies, 13 (2): 209–232, JSTOR 44288829

- Mehra, Parshotam (1974), The McMahon Line and After: A Study of the Triangular Contest on India's North-eastern Frontier Between Britain, China and Tibet, 1904-47, Macmillan, ISBN 9780333157374 – via archive.org

External links