Siege of Shaizar

| Siege of Shaizar | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Crusades | |||||||

John II Komnenos negotiating with the Emir of Shaizar, 13th-century French manuscript | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

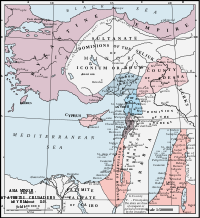

The siege of Shaizar took place from April 28 to May 21, 1138. The allied forces of the Byzantine Empire, Principality of Antioch and County of Edessa invaded Muslim Syria. Having been repulsed from their main objective, the city of Aleppo, the combined Christian armies took a number of fortified settlements by assault and finally besieged Shaizar, the capital of the Munqidhite Emirate. The siege captured the city, but failed to take the citadel; it resulted in the Emir of Shaizar paying an indemnity and becoming the vassal of the Byzantine emperor. The forces of Zengi, the greatest Muslim prince of the region, skirmished with the allied army but it was too strong for them to risk battle. The campaign underlined the limited nature of Byzantine suzerainty over the northern Crusader states and the lack of common purpose between the Latin princes and the Byzantine emperor.

Background

Freed from immediate external threats in the Balkans or in Anatolia, having defeated the Hungarians in 1129, and having forced the Anatolian Turks on the defensive by a series of campaigns from 1130 to 1135, the Byzantine emperor John II Komnenos (r. 1118–1143) could direct his attention to the Levant, where he sought to reinforce Byzantium's claims to suzerainty over the Crusader States and to assert his rights and authority over Antioch. These rights dated back to the Treaty of Devol of 1108, though Byzantium had not been in a position to enforce them. The necessary preparation for a descent on Antioch was the recovery of Byzantine control over Cilicia. In 1137, the emperor conquered Tarsus, Adana, and Mopsuestia from the Principality of Armenian Cilicia, and in 1138 Prince Levon I of Armenia and most of his family were brought as captives to Constantinople.[1][2][3][4][5]

Control of Cilicia opened the route to the Principality of Antioch for the Byzantines. Faced with the approach of the formidable Byzantine army, Raymond of Poitiers, prince of Antioch, and Joscelin II, count of Edessa, hastened to acknowledge the Emperor's overlordship. John demanded the unconditional surrender of Antioch and, after asking the permission of Fulk, King of Jerusalem, Raymond of Poitiers agreed to surrender the city to John. The agreement, by which Raymond swore homage to John, was explicitly based on the Treaty of Devol, but went beyond it. Raymond, who was recognized as an imperial vassal for Antioch, promised the Emperor free entry to Antioch, and undertook to hand over the city in return for the cities of Aleppo, Shaizar, Homs, and Hama as soon as these were conquered from the Muslims. Raymond would then rule the new conquests and Antioch would revert to direct imperial control.[6][7]

Campaign

In February, all merchants and travellers from Aleppo and other Muslim towns were arrested to prevent them from reporting on the developing military preparations. In March, the imperial army, accompanied by a substantial siege train, crossed from Cilicia to Antioch and the contingents from Antioch and Edessa, plus a company of Templars, joined up with it. They crossed into enemy territory and occupied Balat. On April 3 they arrived at Biza'a which held out for five days. A large amount of booty was plundered from the town, which was sent back to Antioch, though the convoy was attacked by a Muslim force and plundered in its turn. It had been hoped that Aleppo could be surprised. However, the most powerful Muslim leader in Syria, Zengi, was besieging nearby Hama, which was held by a Damascene garrison. He had enough warning of the Emperor's operations to quickly reinforce Aleppo. On April 20, the Christian army launched an attack on the city but found it too strongly defended. Kinnamos reports that a lack of water the vicinity of Aleppo was the reason for it not being besieged in earnest. The Emperor then moved the army southward taking the fortresses of Athareb, Maarat al-Numan, and Kafartab by assault, with the ultimate goal of capturing the city of Shaizar. It is probable that Shaizar was chosen because it was an independent Arab emirate, held by the Munqidhite dynasty, and therefore it might not be regarded by Zengi as important enough for him to come to its aid; also possession of Shaizar would have opened the city of Hama to attack.[8][9][10][11]

Siege

The Crusader princes were suspicious of each other and of John, and none wanted the others to gain from participating in the campaign. Raymond also wanted to hold on to Antioch, which was a Christian city; the attraction of lordship over a city like Shaizar or Aleppo, with a largely Muslim population and more exposed to Zengid attack, must have been slight. With the lukewarm interest his allies had in the prosecution of the siege, the Emperor was soon left with little active help from them.[12]

Following some initial skirmishes, John II organised his army into three divisions based on the nationalities of his soldiery: Macedonians (native Byzantines); 'Kelts' (meaning Normans and other Franks); and Pechenegs (Turkic steppe nomads). Each division was equipped with its characteristic arms and equipment, and was paraded before the city in order to overawe the defenders.[13][14]

Although John fought hard for the Christian cause during the campaign in Syria, his allies Raymond of Poitiers and Joscelin of Edessa remained in their camp playing dice and feasting instead of helping to press the siege. Due to their example, the morale of their troops was undermined. The Emperor's reproaches could only goad the two princes into perfunctory and fitful action. Latin and Muslim sources describe John's energy and personal courage in prosecuting the siege. Conspicuous in his golden helmet, John was active in encouraging his troops, supervising the siege engines and consoling the wounded. The walls of Shaizar were battered by the trebuchets of the impressive Byzantine siege train. The Emir's nephew, the poet, writer and diplomat Usama ibn Munqidh, recorded the devastation wreaked by the Byzantine artillery, which could smash a whole house with a single missile.[15][16][17]

The city was taken, but the citadel, protected by its cliffs and the courage of its defenders, defied assault. Tardily, Zengi had assembled a relief army and it moved towards Shaizar. The relief army was smaller than the Christian army but John was reluctant to leave his siege engines in order to march out to meet it, and he did not trust his allies. At this point, Sultan ibn Munqidh, the Emir of Shaizar, offered to become John's vassal, pay a large indemnity and pay yearly tribute. Also offered was a table studded with jewels and an impressive carved cross said to have been made for Constantine the Great, which had been captured from Romanos IV Diogenes by the Seljuk Turks at the Battle of Manzikert. John, disgusted by the behaviour of his allies, reluctantly accepted the offer. On 21 May, the siege was raised.[18][19][20][21]

Aftermath

Zengi's troops skirmished with the retreating Christians, but did not dare to actively impede the army's march. Returning to Antioch, John made a ceremonial entry into the city. However, Raymond and Joscelin conspired to delay the promised handover of Antioch's citadel to the Emperor, and stirred up popular unrest in the city directed at John and the local Greek community. Having heard of a raid by the Anatolian Seljuks on Cilicia, and having been besieged in the palace by the Antiochene mob, John abandoned his demand for control of the citadel. He insisted, however, on a renewal of Raymond and Jocelyn's oaths of fealty. John told them that he would return with his army to implement his treaties with them. He then left Antioch intending to punish the Seljuk sultan Mas'ud (r. 1116–1156) and subsequently to return to Constantinople. John had little choice but to leave Syria with his ambitions only partially realised.[22][23]

The events of the campaign underlined that the suzerainty the Byzantine emperor claimed over the Crusader states, for all the prestige it offered, had limited practical advantages. The Latins enjoyed the security that a distant imperial connection gave them when they were threatened by the Muslim powers of Syria. However, when Byzantine military might was directly manifested in the region, their own self-interest and continued political independence was of greater importance to them than any possible advantage that might be gained for the Christian cause in the Levant by co-operation with the Emperor.[24][25][26]

According to Niketas Choniates's early 13th-century history, John II returned to Syria in 1142 intending to forcibly take Antioch and impose direct Byzantine rule, expecting the local Syrian and Armenian Christian population to defect in support of this campaign.[27] His death in spring of 1143, the result of a hunting accident, intervened before he could achieve this goal. His son and successor, Manuel I (r. 1143–1180), took his father's army back to Constantinople to secure his authority, and the opportunity for the Byzantines to conquer Antioch outright was lost. In the opinion of Michael Angold, the sudden death of John was most opportune for the Latin princes, as they would have had great difficulty in continuing to resist him.[28][29][30]

See also

References

Citations

- ^ Birkenmeier 2002, pp. 90–91

- ^ Angold, pp.154–156

- ^ Kinnamos 1976, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Harris 2014, pp. 88

- ^ Bucossi and Suarez, p. 74

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 213–214.

- ^ Harris 2014, pp. 88–89

- ^ Kinnamos (1976), p. 24

- ^ Runciman 1952, p. 215.

- ^ Harris 2014, pp. 89–90

- ^ Angold, p. 156

- ^ Runciman 1952, p. 216.

- ^ Choniates & Magoulias 1984, p. 17.

- ^ Birkenmeier 2002, pp. 93

- ^ Runciman 1952, p. 216.

- ^ Harris 2014, pp. 89

- ^ Bucossi and Suarez, p. 87

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 215–217.

- ^ Kinnamos 1976, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Choniates & Magoulias 1984, p. 18.

- ^ Harris 2014, pp. 90

- ^ Bucossi and Suarez, pp. 89–90

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 217–218

- ^ Choniates & Magoulias 1984, p. 18

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 216–218; Angold 1984, p. 156.

- ^ Harris 2014, pp. 90

- ^ Choniates & Magoulias 1984, p. 22

- ^ Kinnamos 1976, pp. 27–28, 30–31; Choniates & Magoulias 1984, pp. 24–26; Angold 1984, pp. 157–158.

- ^ Harris 2014, pp. 91

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 224

Sources

Primary

- Choniates, Niketas; Magoulias, Harry J. (trans.) (1984). O City of Byzantium: Annals of Niketas Choniates. Detroit, Michigan: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-81-431764-8.

- Kinnamos, John (1976). Deeds of John and Manuel Comnenus. Translated by Brand, Charles M. New York City: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-23-104080-8 – via the Internet Archive.

Secondary

- Angold, Michael (1984). The Byzantine Empire, 1025–1204: A Political History. London, United Kingdom: Longman. ISBN 9780582294684. ISBN 0-582-49061-8

- Birkenmeier, John W. (2002). The Development of the Komnenian Army: 1081–1180. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-11710-5.

- Bucosssi, A. and Suarez, A.R. (eds.) (2016). John II Komnenos, Emperor of Byzantium: In the Shadow of Father and Son, Routledge, London and New York ISBN 978-1-4724-6024-0

- Harris, Jonathan (2014). Byzantium and the Crusades (2nd ed.). Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1780938318.

- Runciman, Steven (1952). A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100-1187. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press – via Internet Archive.

Further reading

- ibn Munqidh, Usama; Cobb, Paul M. (trans.) (2008). The Book of Contemplation: Islam and the Crusades. London: Penguin Classics. ISBN 9780140455137.

- Ibn al-Qalanisi (2002). The Damascus Chronicle of the Crusades. Translated by H. A. R. Gibb. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-48-642519-1.