Shotgun Willie

| Shotgun Willie | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | June 11, 1973 | |||

| Recorded | February 1973 | |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 36:16 | |||

| Label | Atlantic | |||

| Producer | Arif Mardin, Jerry Wexler, David Briggs | |||

| Willie Nelson chronology | ||||

| ||||

Shotgun Willie is the 16th studio album by American country music singer-songwriter Willie Nelson, released on June 11, 1973. The recording marks a change of style for Nelson, who later stated that the album "cleared his throat". When Nelson refused to sign an early extension of his contract with RCA Records in 1972, the label decided not to release any further recordings. Nelson hired Neil Reshen as his manager, and while Reshen negotiated with RCA, Nelson moved to Austin, Texas, where the ongoing hippie music scene at the Armadillo World Headquarters renewed his musical style. In Nashville, Nelson met producer Jerry Wexler, vice president of Atlantic Records, who was interested in his music. Reshen solved the problems with RCA and signed Nelson with Atlantic as their first country music artist.

The album was recorded in the Atlantic Studios in New York City in February 1973. Nelson and his backup musicians, the Family, were joined by Doug Sahm and his band. After recording several tracks, Nelson was still not inspired. Following a recording session, he wrote "Shotgun Willie"—the song that would become the title track of the album—on the empty packaging of a sanitary napkin while in the bathroom of his hotel room. The album, produced mostly by Arif Mardin with assistance from Wexler and longtime Neil Young collaborator David Briggs, included covers of two Bob Wills songs—"Stay All Night (Stay a Little Longer)" and "Bubbles in My Beer"—that were co-produced by Wexler. Waylon Jennings and Jessi Colter collaborated on the album, providing vocals and guitar.

In spite of poor sales, Shotgun Willie received good reviews and gained Nelson major recognition with younger audiences. The recording was one of the first albums of outlaw country—a new subgenre of country music and an alternative to the conservative restrictions of the Nashville sound, the dominant style in the genre at the time.

Background

In April 1972, after Nelson recorded "Mountain Dew", his final RCA Records single. The label requested Nelson to renew his contract ahead of schedule, and informed him that they would not release any further recordings if he did not sign. Nelson's manager, Neil Reshen, negotiated an agreement with RCA Records to end the contract upon return of US$1,400 that the singer had been overpaid.[2] By that time, Nelson had left Nashville and he moved to Austin, Texas. Austin's burgeoning hippie music scene at venues like Armadillo World Headquarters rejuvenated the singer. His popularity in Austin soared as he played his own brand of music that was a blend of country, folk, and jazz influences.[3] Nelson had felt creatively hamstrung by RCA's strict recording practices and frustrated at not being permitted to use his touring band in the studio. In 2015, Nelson remembered his move to Austin: "I liked this new world. It fit me to a T. I never did like putting on stage costumes, never did like trim haircuts, never did like worrying about whether I was satisfying the requirements of a showman. It felt good to let my hair grow. Felt good to get on stage in the same jeans I'd been wearing all damn day.”[4]

During a trip to Nashville, Tennessee, Nelson attended a party in Harlan Howard's house, where he sang the songs that he had written for the album Phases and Stages. Another guest was Atlantic Records vice-president Jerry Wexler, who previously had produced works for artists such as Ray Charles and Aretha Franklin. Wexler was interested in Nelson's music, so when Atlantic opened a country music division of their label, he offered Nelson a contract that gave him more creative control than his deal with RCA.[5] When Nelson asked Wexler if he was worried about the music not being commercial, Wexler replied, "Fuck commerce. You're going for art. You're going for the truth."[6] In his autobiography Nelson later recalled, ""I'd never heard a record man talk that way. On the spot, I decided that Wexler was my man."[6] When Nelson was released from his RCA contract, he signed with Atlantic for US$25,000 per year, becoming the label's first country artist.[7]

Recording

The recording sessions took place in February 1973.[8] Wexler provided Nelson and his band with a studio in New York City, where most of the recordings were produced.[9] Additionally, parts of the album were recorded in the Quadraphonic studios in Nashville, as well as in the Sam Phillips Recording studio in Memphis.[10] Doug Sahm and his band were also invited to the New York sessions.[7] During the first session, Nelson recorded the songs for The Troublemaker. Later, he proceeded with Shotgun Willie.[9]

Wexler had encouraged Nelson after singing the gospel album to start with the new one, to couple old material with new, and covers.[11] He initially recorded twenty-three tracks along with his and Sahm's band, but Nelson still was not inspired. He wrote the title song after one of the sessions.[7] Pacing in his hotel room, he went to the bathroom, where he sat on the toilet and took the empty envelope from a sanitary napkin from the sink, and penned the song on that.[12] The title of the song refers to the nickname Nelson received after his daughter, Susie, warned him of the domestic abuse suffered by her sister Lana. Nelson drove to Lana's house, where he fought with her husband Steve Warren, and threatened to kill him if he repeated the assault. Soon after Nelson returned home, Warren arrived in his truck with his brothers. The men shot at the house with .22 caliber rifles. In response, Nelson and Paul English shot at the aggressors that retreated. When they returned later, Nelson took English's M1 Garand and shot the truck, causing them to surrender.[13][14] He completed the rest of the song with a reference to John T. Floore, owner of the honky-tonk Floore's Country Store.[15] After hearing the completed song, Wexler decided that the album was to be named after it.[16] Nelson later recalled, "Kris Kristofferson told me later the song 'Shotgun Willie' was 'mind farts.' Maybe so, but I thought of it more as clearing my throat."[17]

Most of the tracks were produced by Arif Mardin, with the exception of the two Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys covers, "Stay All Night (Stay a Little Longer)" and "Bubbles in My Beer," which were produced by Mardin and Jerry Wexler.[18] In his biographical book about Nelson, Joe Nick Patoski noted that the recording of the album "was sloppy and chaotic, technically and artistically uneven, with horns and strings occasionally bumping up against the musical core of Bee Spears, Paul English, Bobbie Nelson, Jimmy Day, and Willie...The music was more country than what was being played on the radio but somehow different. If there were slips and flubs, they stayed in."[19] The album included Johnny Bush's Whiskey River",[7] which later became Nelson's show opener. Nelson remembered in his autobiography: "In 1972, Johnny Bush called me with part of a song he'd written with Paul Stroud. I took the song the way it was but adapted it to my style, which was more blues than rock."[20] Shotgun Willie also contained "A Song for You," written by Leon Russell. The song would become a number often performed by Nelson. Nelson added: "He knocked me out...I understood how his image – with his crazy stovepipe hat and dark aviator glasses – added to his mysterious allure. Beyond the mystery, though, I heard that his musical roots and mine were the same: Hank Williams, Bob Wills, country black blues..."[21]

Nelson later declared that with Wexler's producing he "cranked out songs, one after the other" and that "the atmosphere was right". The singer added: "I felt free to tap into my imagination, no hold barred".[16] During the recording, there were rumors that there would be appearances by George Jones, Leon Russell, and Kris Kristofferson that ultimately did not happen. Waylon Jennings joined the backing band playing guitar, and provided backing vocals for "Stay All Night (Stay a Little Longer)", along with Jessi Colter and Doug Sahm.[22] Several journalists were on attendance during the recording. Ed Ward from Creem later commented: "I'd underestimated the professionalism of all concerned, not to mention the core ensemble of musicians themselves, who decided to test the sound of the studio with a spirited version of 'Under the Double Eagle,' which left me awestruck: Willie wasn't only a great songwriter, he was a goddamn virtuoso on that battered Martin guitar of his!"[23]

Release and reception

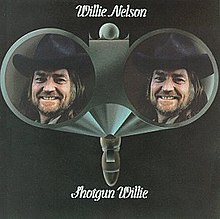

As the album was released in June 1973, it received good reviews but did not sell well.[12] Meanwhile, in Austin, it sold more copies than earlier records by Nelson did nationwide.[24] The recording led the singer to a new style; he later stated regarding his new musical identity that Shotgun Willie had "cleared his throat."[12] It became his breakthrough record, and one of the first of the outlaw movement, music created without the influence of the conservative Nashville Sound. The album—the first to feature Nelson with long hair and a beard on the cover—gained him the interest of younger audiences.[25] It peaked at number 41 on Billboard's Top Country Albums and the songs "Shotgun Willie" and "Stay All Night (Stay A Little Longer)" peaked at number 60 and 22 on Hot Country Songs respectively.[26][27]

Atlantic Records reissued Shotgun Willie on CD in 1990.[28] It was reissued by the label on CD and LP in 2009,[29] and again in 2021 on LP and digital download.[30]

Critical reception

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| Rolling Stone | Highly favorable[31] |

| Christgau's Record Guide | B+[32] |

| Billboard | Favorable[33] |

| Texas Monthly | Favorable[34] |

| Fort Worth Star-Telegram | Highly favorable[35] |

| Arizona Republic | Favorable[36] |

| Philadelphia Daily News | Favorable[37] |

| Detroit Free Press | Favorable[38] |

| AllMusic | |

Rolling Stone called the album "flawless" and considered that Nelson "finally demonstrates why he has for so long been regarded as a Country & Western singer-songwriter's singer-songwriter". The reviewer concluded: "At the age of 39, Nelson finally seems destined for the stardom he deserves".[31] Robert Christgau wrote: "This attempt to turn Nelson into a star runs into trouble when it induces him to outshout Memphis horns or Western swing."[32] Billboard wrote: "This is Willie Nelson at his narrative best. He writes and sings with the love and the hurt and the down-to-earth things he feels, and he has few peers."[33] Texas Monthly praised Nelson and Wexler regarding the change in musical style:"They've switched his arrangements from Ray Price to Ray Charles—the result: a revitalized music. He's the same old Willie, but veteran producer Jerry Wexler finally captured on wax the energy Nelson projects in person".[34]

The Fort Worth Star-Telegram started its review by declaring: "1973 could be the year country music 'rediscovers' Willie Nelson." Critic Bill McAllister mentioned the support that Texas Longhorns football coach Darrell Royal gave Nelson and his music. The reviewer determined that Shotgun Willie "displays unique musical abilities to excellent advantage" and remarked that Nelson was "often called the Cole Porter of country music".[35] The Arizona Republic presented Nelson as "an accomplished baritone and composer", as the publication appealed the readers to "lend old Shotgun an ear and find out what C&W music sounds like when it's not sung through the nose, or hat".[36] The Philadelphia Daily News considered that the record had "some ups and downs" but that Nelson made the tracks "real winners". The publication deemed the singer "real country, not a hip version of it".[37]

The Detroit Free Press delivered a favorable review. Critic Bob Talbert noted that Nelson and country songwriters as "authentic people poets". The reviewer described the content of the songs as written by "people-type people. Bleeders and boozers and dreamers and drinkers. Sad and joyous people."[38] School Library Journal wrote: "Willie Nelson differs (from) rock artists framing their music with a country & western façade — in that he appears a honky-tonk stardust cowboy to the core. This album abounds in unabashed sentimentalism, nasal singing, lyrics preoccupied with booze, religion, and love gone bad, and stereotyped Nashville instrumentation (twangy steel guitars, fiddles, and a clean rhythm section characterized by the minimal use of bass drum and cymbals, both of which gain heavy mileage with rock performers).[40]

Stephen Thomas Erlewine wrote in his review for AllMusic: "Willie Nelson offered his finest record to date for his debut – possibly his finest album ever. Shotgun Willie encapsulates Willie's world view and music, finding him at a peak as a composer, interpreter, and performer. This is laid-back, deceptively complex music, equal parts country, rock attitude, jazz musicianship, and troubadour storytelling".[39] Nelson biographer Joe Nick Patoski writes that Shotgun Willie was Nelson's "creative declaration of independence."[41]

Track listing

All tracks are written by Willie Nelson, except where noted[10]

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Shotgun Willie" | 2:40 |

| 2. | "Whiskey River" (Johnny Bush, Paul Stroud) | 4:05 |

| 3. | "Sad Songs and Waltzes" | 3:08 |

| 4. | "Local Memory" | 2:19 |

| 5. | "Slow Down Old World" | 2:54 |

| 6. | "Stay All Night (Stay a Little Longer)" (Bob Wills, Tommy Duncan) | 2:36 |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Devil in a Sleepin' Bag" | 2:40 |

| 2. | "She's Not for You" | 3:15 |

| 3. | "Bubbles in My Beer" (Tommy Duncan, Cindy Walker, Bob Wills) | 2:34 |

| 4. | "You Look Like the Devil" (Leon Russell) | 3:26 |

| 5. | "So Much to Do" | 3:11 |

| 6. | "A Song for You" (Leon Russell) | 4:20 |

Personnel

|

|

Charts

| Chart (1973) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| US Top Country Albums (Billboard)[42] | 41 |

References

- ^ Freeman, Doug (October 30, 2020). "Jerry Jeff Walker Brought the Magic". Austin Chronicle. Retrieved July 22, 2023.

- ^ Reid 2004, pp. 223–224.

- ^ Reid 2004, p. 79.

- ^ Nelson & Ritz 2015, p. 215.

- ^ Kienzle 2003, pp. 250–251.

- ^ a b Nelson & Ritz 2015, p. 220.

- ^ a b c d Reid 2004, p. 224.

- ^ Inter Pub 1994, p. 169.

- ^ a b Freeman, Doug (January 18, 2008). "Sister Bobbie". The Austin Chronicle. Austin Chronicle Corp. Retrieved June 12, 2012.

- ^ a b c Nelson, Willie 1973.

- ^ Nelson & Ritz 2015, p. 221.

- ^ a b c Tichi 1998, p. 341.

- ^ Nelson & Shrake 2000, p. 163.

- ^ Reid & Sahm 2010, p. 105.

- ^ Nelson & Ritz 2015, p. 222.

- ^ a b Nelson & Ritz 2015, p. 223.

- ^ Nelson & Shrake 1988, p. 163.

- ^ Ertegun & Richardson 2001, p. 542.

- ^ Patoski 2008, pp. 252–253.

- ^ Nelson & Ritz 2015, p. 209.

- ^ Nelson & Ritz 2015, p. 192.

- ^ Reid & Sahm 2010, pp. 105–106.

- ^ Streissguth 2013, p. 111.

- ^ Cartwright 2000, p. 278.

- ^ Davis 2004, p. 298.

- ^ "Willie Nelson Chart History - Top Country Albums". Billboard. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ "Willie Nelson - Chart History - Singles". Billboard. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ Nelson, Willie 1990.

- ^ Nelson, Willie 2009.

- ^ Nelson, Willie 2021.

- ^ a b Ditlea, Steve (August 30, 1973). "Review: Willie Nelson – Shotgun Willie". Rolling Stone. Wenner Media LLC. Retrieved September 4, 2011.

- ^ a b Christgau, Robert (1981). "Consumer Guide '70s: N". Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies. Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 089919026X. Retrieved March 8, 2019 – via robertchristgau.com.

- ^ a b "Billboard's Top Album Picks – Country Picks". Billboard. Vol. 85, no. 25. Emmis Communications. June 23, 1973. p. 76. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved September 21, 2011.

- ^ a b Roth, Don; Reid, Jan (November 1973). "The Coming of Redneck Hip". Texas Monthly. 1 (10). Emmis Communications: 75. ISSN 0148-7736. Retrieved September 21, 2011.

- ^ a b McAllister, Bill 1973, p. 3-A.

- ^ a b Walker, Gus 1973, p. N-6.

- ^ a b Aregood, Rich 1973, p. 43.

- ^ a b Talbert, Bob 1973, p. 15-D.

- ^ a b Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Shotgun Willie Overview". Allmusic. Rovi Corporation. Retrieved September 5, 2011.

- ^ Hoffmann 1973, p. 49.

- ^ Patoski 2008, p. 254.

- ^ "Willie Nelson Chart History (Top Country Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- Sources

- Aregood, Rich (June 15, 1973). "Is Nilsson Kidding us With His New Album". Philadelphia Daily News. Vol. 49, no. 64. Retrieved May 3, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Cartwright, Gary (2000). Turn Out the Lights: Chronicles of Texas in the 80's and 90's. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-71226-3.

- Davis, Steven (2004). Texas Literary Outlaws: Six Writers in the Sixties and Beyond. Fort Worth, Texas: TCU Press. ISBN 978-0-87565-285-6.

- Hoffmann, Frank (September 1973). "Shotgun Willie". School Library Journal. R. R. Bowker. ISSN 0362-8930.

- Ertegun, Ahmet; Richardson, Perry (2001). "What'd I Say?": The Atlantic Story: 50 Years of Music. New York: Welcome Rain. ISBN 978-1-56649-048-1.

- Kienzle, Richard (2003). Southwest Shuffle: Pioneers of Honky-Tonk, Western Swing, and Country Jazz. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-94103-7.

- McAllister, Bill (August 4, 1973). "Darrell, You and a Good Album--All Helping 'Rediscover' Willie Nelson". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. Vol. 93, no. 185. p. 3. Retrieved May 3, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Nelson, Willie; Shrake, Bud (1988). Willie: An Autobiography. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0671680756.

- Nelson, Willie (1973). Shotgun Willie (LP). Atlantic Records. SD 7262.

- Nelson, Willie (1990). Shotgun Willie (CD). Atlantic Records. 7262-2.

- Nelson, Willie; Shrake, Erwin (2000). Willie: An Autobiography. New York: Cooper Square Press. ISBN 978-0-8154-1080-5.

- Nelson, Willie (2009). Shotgun Willie (CD, LP). Atlantic Records. R1 7262.

- Nelson, Willie (2021). Shotgun Willie (LP, digital download). Atlantic Records. RCV1 649775.

- Nelson, Willie; Ritz, David (2015). It's A Long Story: My Life. Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-33931-5.

- Patoski, Joe Nick (2008). Willie Nelson: An Epic Life. Hachette Digital. ISBN 978-0-316-01778-7.

- Reid, Jan (2004). The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-70197-7.

- Reid, Jan; Sahm, Shawn (2010). Texas Tornado: The Times & Music of Doug Sahm. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-72196-8.

- Streissguth, Michael (2013). Outlaw: Waylon, Willie, Kris, and the Renegades of Nashville. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0062038180.

- Talbert, Bob (June 17, 1973). "A Man Who Whatches Bubbles in My Beer". Detroit Free Press. Vol. 143, no. 44. Retrieved May 3, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Tichi, Cecilia (1998). Reading Country Music: Steel Guitars, Opry Stars, and Honky-Tonk Bars. Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-2168-2.

- Inter Pub (1994). The Stars of country music. Publications International. ISBN 978-0-785-30872-0.

- Walker, Gus (July 8, 1973). "Willie recites lyrics as well as sings 'em". Arizona Republic. Vol. 84, no. 53. Retrieved May 3, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

External links

- Shotgun Willie at Discogs (list of releases)