Shapinsay

| Scots name | Shapinsee[1] |

|---|---|

| Old Norse name | Hjálpandisey |

| Meaning of name | Possibly Old Norse for 'helpful island' or 'judge's island' |

Cannon decorate the quayside of Balfour Harbour on Shapinsay, the round tower in the background is The Douche | |

| Location | |

| OS grid reference | HY505179 |

| Coordinates | 59°03′N 2°53′W / 59.05°N 2.88°W |

| Physical geography | |

| Island group | Orkney |

| Area | 2,948 hectares (11.4 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 29 [2] |

| Highest elevation | Ward Hill 64 metres (210 ft) |

| Administration | |

| Council area | Orkney Islands |

| Country | Scotland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 307[3] |

| Population rank | 27 [2] |

| Population density | 10.4 people/km2[3][4] |

| Largest settlement | Balfour |

| References | [4][5][6][7][8] |

Shapinsay (/ˈʃæpɪnziː/, Scots: Shapinsee) is one of the Orkney Islands off the north coast of mainland Scotland. With an area of 29.5 square kilometres (11.4 sq mi), it is the eighth largest island in the Orkney archipelago. It is low-lying and, with a bedrock formed from Old Red Sandstone overlain by boulder clay, fertile, causing most of the area to be used for farming. Shapinsay has two nature reserves and is notable for its bird life. Balfour Castle, built in the Scottish Baronial style, is one of the island's most prominent features, a reminder of the Balfour family's domination of Shapinsay during the 18th and 19th centuries; the Balfours transformed life on the island by introducing new agricultural techniques. Other landmarks include a standing stone, an Iron Age broch, a souterrain and a salt-water shower.

There is one village on the island, Balfour, from which roll-on/roll-off car ferries sail to Kirkwall on the Orkney Mainland. At the 2011 census, Shapinsay had a population of 307. The economy of the island is primarily based on agriculture with the exception of a few small businesses that are largely tourism-related. A community-owned wind turbine was constructed in 2011. The island has a primary school but, in part due to improving transport links with mainland Orkney, no longer has a secondary school. Shapinsay's long history has given rise to various folk tales.

Etymology

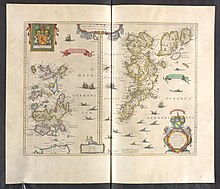

Unlike most of the larger Orkney islands, the derivation of the name 'Shapinsay' is not obvious. The final 'ay' is from the Old Norse for island, but the first two syllables are more difficult to interpret. Haswell-Smith suggests the root may be hjalpandis-øy (helpful island) owing to the presence of a good harbour, although anchorages are plentiful in the archipelago.[4] The first written record dates from 1375 in a reference to Scalpandisay, which may suggest a derivation from Judge's island. Another suggestion is Hyalpandi's island, although no one of that name is known to be associated with Shapinsay.[5] Blaeu's 1654 Atlas Novus includes a map of the island and names it Siapansa Oy, but the descriptive text lists it as Shapinsa.[9]

History

Early history

Standing stones show evidence of the island's human occupation since Neolithic times. According to Tacitus, the Roman general Agricola subdued the inhabitants of the Orkney Islands, and a local legend holds that he landed on Shapinsay. During the 18th century, a croft named Grukalty was renamed Agricola (which is also Latin for "farmer"). Roman coins have been found on Shapinsay, but they may have been brought to the island by traders.[10][11]

Shapinsay is mentioned in the Norse sagas: The Saga of Haakon Haakonsson states that Haakon IV of Norway anchored in Elwick Bay before sailing south to eventual defeat at the Battle of Largs.[4]

Atlas Novus included a map and various descriptions of the island. The harbour at Elwick is described as “quite commodious”, and the dwelling of “Sound” is praised.[14] The estate of Sound, which covered the western part of the island, had passed from the Tulloch family to the Buchanan family in 1627. John Buchanan was a royal servant and his wife Margaret Hartsyde was from a Kirkwall family.[15] In 1674, Arthur Buchanan built the new house of Sound, which was situated 250 metres west of where Balfour Castle now stands.[16] The atlas’s description of Orkney by Walter Stewart then goes on to note that Shapinsay had one minister at the time.[14][17]

18th century

The 18th century saw the beginnings of change to agriculture on Shapinsay, courtesy of the Balfour family. Arthur Buchanan’s granddaughter married James Fea, who supported the Jacobite rising of 1715; his house was burned by Hanoverian troops in revenge. The estate was acquired by Andrew Ross, Stewart Depute in Orkney of the Earl of Morton[Note 1] and Ross's heirs, the Lindsay brothers, sold the estate to Thomas Balfour in 1782.[10][19] Balfour had previously rented the Bu of Burray, a large manor farm on another Orkney island, but had insufficient wealth to acquire the estate even though his wife received a large inheritance from her brother. To raise the necessary funds of £1,250, Balfour sold his military commission and borrowed from his brother.[19] Once installed on the island, Balfour built a new house, Cliffdale, and founded the village of Shoreside, now known as Balfour. He also reformed the local agriculture, enclosing fields and constructing farm buildings.[20]

The last person to be executed in Orkney was Marjory Meason, a native of Shapinsay, in 1728. She was a young servant who was hanged in Kirkwall for the murder of a child. The execution is recorded as requiring 24 armed men, not including officers, and costing £15 8s.[10]

During this period, burning kelp was a mainstay of the island economy. More than 3,048 tonnes (3,000 long tons) of burned seaweed were produced per annum to make soda ash, bringing in £20,000 for the inhabitants.[4] Thomas Balfour's income from the kelp industry brought him four times the income that farming did.[21]

19th century

The 19th century saw radical change in Shapinsay. Thomas Balfour's grandson, David Balfour, transformed the island after inheriting the family estate, which by 1846 encompassed the whole of Shapinsay. Most of the land was divided into fields of 4 hectares (10 acres),[22] a feature still apparent today.[6] Tenants were required to enclose and drain the land or pay for the estate to do it in the form of a surcharge added to their rents. In 1846, 303 hectares (1.17 sq mi) on Shapinsay consisted of arable land. By 1860, that had trebled to more than 890.3 hectares (3.44 sq mi).[22] New crops and breeds of cattle and sheep were also introduced.[10] Balfour's reforms were described as "the fountain and origin" of Orkney improvement.[23]

Thomas Balfour had enemies amongst the Orkney establishment, and one of them described his attempts in disparaging language.[Note 2] Thomson notes that the wholesale clearance of cottars from their land and re-settlement in the planned village turned them into estate employees, which may not have been seen by them as a “change for the better”.[20] The process by which his son David came to own the whole island was also part of a controversial process of enclosure. At the beginning of the 19th century, 45% of all Orkney and fully 2,956 acres of Shapinsay was common land.[24] Today, only 624 acres of commons remains throughout Orkney.[25] This process of clearance and enclosure, common throughout Scotland at this time,[26] was accompanied by an estrangement between landowner and tenants. For example, Thomas Balfour went to the grammar school in Kirkwall as had his father before him, but two of his sons were educated at the prestigious Harrow School in southern England.[27] The power of the landowners is suggested by an incident during his grandson David's period of ownership. Various church elders complained about what they considered to be immoral behaviour at a social event (men were allowed to dance with women) so Balfour had them evicted from the island.[28]

David Balfour also gave the island its most noticeable landmark when he recruited an Edinburgh architect, David Bryce, to transform Cliffdale House into the Scottish Baronial Balfour Castle.[29][30] Other buildings he added to the island include the porter's lodge (now a public house called The Gatehouse), a water mill, a school, and a gasworks that remained operational until the 1920s.[10] The gasworks is in the form of a round tower with a corbelled parapet of red brick and carved stones—including one possibly removed from Noltland Castle on Westray, which is inscribed with the year 1725. The structure appears to be fortified, in accordance with Balfour's intention to give the village a medieval appearance.[31][32] David Balfour was also responsible for the construction of Mill Dam, a wetland which was once the water supply for the mill and is now an RSPB nature reserve.[10]

Fishing for herring and cod grew in importance during the 19th century. Herring fishing was expanding generally in Scotland at that time, with fishing stations being set up in remote areas. Herring fishing began in 1814 on Stronsay and soon spread throughout the Orkney Islands.[33] By the middle of the century, Shapinsay had 50 herring boats.[34] Cod became important largely because the Napoleonic Wars forced English fishing boats to fish further north. Local fishermen, who had been catching fish using lines from small boats for centuries, began trawling for cod, though fishing was largely a part-time venture.[35] Helliar Holm's beaches were used to dry both herring and cod after they had been salted. With the end of the Napoleonic Wars, which led to cheaper sources of soda ash becoming available from continental Europe, the kelp industry collapsed by 1830.[10] This collapse fueled agricultural reform, as crofters accustomed to earning a second income had to now earn more from farming.[35]

20th century

Orkney was a strategic site during both World Wars. In 1917, during the First World War, the 836-tonne (823-long-ton) Swiftsure was hit by a mine 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) east of Haco's Ness and sank in 19 metres (62 ft) of water with the loss of a single life. The site of the wreck was not discovered until 1997.[36]

The Balfour estate sold its farms on Shapinsay between 1924 and 1928. This was a common occurrence in Orkney at the time as wealthy landowners moved to more lucrative forms of investment. Farms were generally sold to the sitting tenant or to their neighbours who wished to expand.[37]

During the Second World War, gun batteries were built on the island. A twin six pounder emplacement at Galtness Battery on the coast at Salt Ness protected the Wide Firth from German torpedo boats. A Castle Battery was operational from 1941 to 1943, as was an anti-aircraft battery.[10]

Mechanised implements came to the island, particularly after the Second World War, and the amount of land given over to growing grass increased. The growing of grain (with the exception of barley) and turnips steadily declined as these were replaced as winter fodder for livestock by silage, usually harvested by mechanical forage harvesters.[Note 3] The trend towards more intensive farming began to be partially reversed by the end of the century as more environmentally friendly practices were encouraged by government and European Union grants. Some of the land is managed under a Habitat Creation Scheme, which aims to encourage natural vegetation, wild flowers and nesting birds by limiting grazing and reducing the use of chemical fertilisers.[39]

Mains electricity arrived on Shapinsay in the 1970s, when an underwater cable was laid from Kirkwall.[40] Tourism became important in the latter half of the century; the first restaurant to incorporate bed and breakfast facilities opened in 1980.[40] Before 1995, the island had a secondary school but lost this because of falling enrolment and improved transport links with Kirkwall, to where Shapinsay secondary pupils now travel.[40] The shorter ferry crossing times enabled Shapinsay residents to work in Kirkwall, making it a "commuter isle".[41]

Geography

With an area of 2,948 hectares (11 sq mi), Shapinsay is the 8th largest Orkney island and the 29th largest Scottish island. The highest point of Ward Hill is 64 metres (210 ft) above sea level.[4] The east coast is composed of low cliffs and has several sea caves, including the geo at the extreme northern tip known as Geo of Ork.[10] Elwick Bay is a sheltered anchorage on the south coast, facing the Orkney mainland; the island's largest settlement, Balfour, is at the western end of the bay.[6] When seen from the air Shapinsay’s square ten-acre fields and straight roads are an obvious feature of the landscape. These are the result of David Balfour’s 19th century “improvments”.[42][6]

The island has several ayres, or storm beaches, which form narrow spits of shingle or sand cutting across the landward and seaward ends of shallow bays. They can sometimes cut off a body of water from the sea, forming shallow freshwater lochs known as oyces.[43][44] Examples include Vasa Loch and Lairo Water.[45]

There are several small islands in the vicinity including Broad Shoal, Grass Holm and Skerry of Vasa. Helliar Holm is a tidal islet at the eastern entrance to the main harbour at Balfour; it has a small lighthouse and a ruined broch. The String, a stretch of water that lies between Helliar Holm and the mainland, has strong tidal currents.[4]

Shapinsay has a bedrock formed from Old Red Sandstone, which is approximately 400 million years old and was laid down in the Devonian period. These thick deposits accumulated as earlier Silurian rocks, uplifted by the formation of Pangaea, eroded and then deposited into river deltas. The freshwater Lake Orcadie existed on the edges of these eroding mountains, stretching from Shetland to the southern Moray Firth.[46] The composition of Shapinsay is mostly of the Rousay flagstone group from the Lower Middle Devonian, with some Eday flagstone in the southeast formed in wetter conditions during the later Upper Devonian. The latter is regarded as a better quality building material than the former.[4] At Haco's Ness in the south east corner of the island is a small outcrop of amygdaloidal diabase. The island is overlain with a fertile layer of boulder clay formed during the Pleistocene glaciations.[10][47][48]

Flora and fauna

The island's bird life is rich in waders such as curlew and redshank, found at The Ouse and Veantro Bay, and gull and tern colonies on the rockier shores and cliffs. Pintail, shovelers and whooper swans are regular summer visitors, and there are breeding populations of shelducks, hen harriers and Arctic skuas.[49] There is an introduced population of red-legged partridges.[50] Otters can be seen at the Ouse, Lairo Water and Vasa Loch, and at various places around the coast along with common seals and Atlantic grey seals.[51] The island has a RSPB reserve at Mill Dam[52] and a Scottish Wildlife Trust reserve at Holm of Burghlee in the southeast.[53][42] Mill Dam is home to the great yellow bumblebee, one of the rarest bumblebees in the UK.[52][54]

Shapinsay has very few stands of trees. The two largest are on the grounds of Balfour Castle and the southwest shore of Loch of Westhill 1.5 kilometres (0.93 mi) to the north.[6] The coastlines of Orkney’s islands, including Shapinsay, are well-known for their abundant and colourful spring and summer flowers including sea aster, sea squill, sea thrift, common sea-lavender, bell and common heather.[55] The lichen Melaspilea interjecta, which is endemic to Scotland, is found in only three locations, including Shapinsay.[56][57]

Demography

| Year | Pop. | Year | Pop. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1798 | 730 | 1911 | 718 |

| 1841 | 935 | 1921 | 624 |

| 1851 | 899 | 1931 | 584 |

| 1861 | 973 | 1951 | 487 |

| 1871 | 949 | 1961 | 346 |

| 1881 | 974 | 1981 | 345 |

| 1891 | 903 | 1991 | 322 |

| 1901 | 769 | 2001 | 300 |

| 2011 | 307 |

The highest recorded population for Shapinsay is 974, in 1881. Since then, the population of the island has steadily declined; less than a third of that number was recorded in the 2001 census. The rate of absolute population loss was lower in the last decades of the 20th century than it had been in the first half of that century. In 2001, Shapinsay had a population of 300, a decline of 6.8% from 322 in 1991. This was greater than the population decline for Orkney overall in the same period, which was 1.9%. However, the loss in population on Shapinsay was less than that experienced by most Orkney islands, most of which experienced declines of more than 10%. The number of persons per hectare on Shapinsay was 0.1, similar to the 0.2 persons per hectare across Orkney.[58][59] At the time of the 2011 census the usually resident population had increased to 307.[3] During the same period Scottish island populations as a whole grew by 4% to 103,702.[60]

Of the island's 300 inhabitants recorded in 2001, 283 were born in the United Kingdom (227 in Scotland and 56 in England). Seventeen were born outside the United Kingdom (four elsewhere in Europe, four in Asia, four in North America, one in South America and four in Oceania). By age group, 85 of the inhabitants were under 30 years of age, 134 were aged between 30 and 59, and 71 were age 60 and over.[61]

Notable buildings

Balfour Castle dominates views of the southwest of the island and can be seen from the tower of St. Magnus Cathedral in Kirkwall. The castle library features a secret passage hidden behind a false set of bookshelves. The Balfours escaped unwelcome visitors through this passageway, which leads to the conservatory door. Another feature of the castle is the stags' heads with gaslights at the tips of their antlers, although these are no longer used as working lights. The castle grounds feature deciduous woodland (now rare in Orkney) and 2 acres (8,100 m2) of walled gardens.[62] Though built around an older structure that dates at least from the 18th century, the present castle was built in 1847, commissioned by Colonel David Balfour, and designed by Edinburgh architect David Bryce.[29][30]

Other buildings constructed by David Balfour include the Dishan Tower, known locally as The Douche. This is a saltwater shower building with a dovecote on top. A local landmark due to its high visibility when approaching the island by sea, the building is now in a serious state of disrepair, the roof having collapsed.[63]

A more ancient dwelling on Shapinsay is the Iron Age Broch of Burroughston. David Balfour arranged for the site to be excavated by the archaeologists George Petrie and Sir William Dryden in 1861.[Note 4] The site was neglected after the excavation, slowly filling up with vegetation and rubble before being cleared in 1994.[64] Only the interior of this partially buried building has been excavated, allowing visitors to look down into the broch from the surrounding mound. The surviving drystone walls rise to about three metres (10 ft) and are more than four metres (13 ft) thick in some places.[65]

Shapinsay Heritage Centre is located in Balfour's former smithy, along with a craft shop and a cafe. The castle's former gatehouse is now the village public house.[56]

Economy

In common with the other Orkney islands, Shapinsay is fertile agricultural land, with farms specialising in beef and lamb which export thousands of cattle and sheep annually.[51][66] Shapinsay has an active agricultural association which hosts an annual agricultural show, as well as other regular events.[67]

The Shapinsay development trust has created a community plan for the island and owns a wind turbine, which was erected in August 2011 after the community voted for its construction.[68] According to the development trust, the turbine could earn more than £5 million during its 25-year lifetime.[69] In 2022-23 Shapinsay Renewables Ltd., which operates the wind turbine, made a gift aid payment of just under £134,000 to the development trust.[70] In both 2022 and 2023 the Development Trust received funding to develop affordable rental housing on the island[71][72] and in 2023 they also opened a newly refurbished heritage centre and cafe.[73]

Small businesses on Shapinsay include a jam and chutney manufacturer, which uses traditional methods.[74] Balfour Castle was run as a hotel by the family of Captain Tadeusz Zawadzki, a Polish cavalry officer, but is now in use as a private house.[75] There is a salmon fish farm off Shapinsay.[76]

Transport

Orkney Ferries provides transport for pedestrians and vehicles, proximity to Kirkwall permitting closer contacts with the Orkney Mainland than is possible for most of the other North Isles. There are six crossings per day, the journey lasting about 25 minutes.[77][41] Between 1893 and 1964, the island was served by the steamer Iona which was originally owned by John Reid and purchased by William Dennison in 1914. After 1964, the converted trawler Klydon [78] and then the Clytus, an ex Clyde pilot vessel operated by the government-owned Orkney Islands Shipping Company[79] ran on this service. The current ferry is the MV Shapinsay which docks at the slipway at Balfour on arrival.[80][81] Orkney is to trial two electric ferries after Artemis Technologies, based in Belfast, were awarded more than £15m of funding by the UK government's Zero Emission Vessels and Infrastructure Fund in 2023. One of the vessels will ferry passengers from Kirkwall, to Shapinsay and the nearby islands of Rousay, Egilsay and Wyre.[82] The Orkney Islands Council has also considered building a tunnel to the Orkney Mainland.[83]

The development trust offers electric bicycles for hire[84] and operates 3 electric vehicles which are available to residents, community groups on the island and visitors.[85]

Education and culture

Shapinsay has a primary school, which in the 2022-23 academic year had 23 pupils.[86] The school doubles as a community centre and is host to a learning centre supported by the UHI Millennium Institute. This centre uses the internet, email and video-conferencing to allow students in Shapinsay to study without leaving the island.[87]

In December 2006, the pupils staged a joint Christmas show with a school in Grinder, Norway, 875 kilometres (544 mi) from Shapinsay. The schools used the internet to collaborate, supported by BT Group (BT), which upgraded the school's broadband connection. The finale of the show involved the Norwegian pupils singing Away in a Manger in English while the Shapinsay pupils responded with En Stjerne Skinner I Natt in Norwegian. This multilingual collaboration was somewhat easier for the Grinder pupils, who are taught English from the age of six.[88] This collaboration was part of an ongoing relationship between the schools, whose children exchange letters and cards. Shapinsay school's headteacher has visited the Norwegian school, and there are plans for a reciprocal visit in 2008.[89]

Shapinsay Community School has gained a Silver Award under the international Eco-Schools programme. School pupils have carried out an energy audit, helped to plant more than 600 trees close to the school and carried out energy saving campaigns.[90][91] Shapinsay pupils have also won an award from the Scottish Crofters Commission for producing a booklet on crofting on the island.[92]

Folklore

Cubbie Roo, the best known Orcadian giant, has a presence on Shapinsay. He was originally based on the historical figure Kolbein Hrúga, who built Cubbie Roo's Castle in 1150 on the isle of Wyre, which is possibly the oldest castle in Scotland, and was mentioned in the Orkneyinga Saga.[4] The figure Cubbie Roo has departed far from his historical origins and has become a giant in the fashion that Finn MacCool (legendary builder of the Giant's Causeway) has in parts of Scotland and Ireland. He is said to have lived on the island of Wyre and used Orkney's islands as stepping stones. Many large stones on Orkney islands, including Shapinsay, are said to have been thrown or left there by the giant. Cubbie Roo's Burn is a waterway on Shapinsay that flows through a channel called Trolldgeo. Cubbie Roo's Lade is a pile of stones on the shore near Rothiesholm Head, the westmost point of Stronsay. This is supposedly the beginning of a bridge between the two islands that the giant had failed to complete. The name derives from the Old Norse trolla-hlad, meaning "giant's causeway".[93]

In 1905, The Orcadian newspaper reported that a strange creature had been seen off the coast of Shapinsay. It was reportedly the size of a horse, with a spotted body covered in scales. Opinion on the creature's origin was divided, with some islanders believing it to be a sea serpent, while others opined that it was merely a large seal.[94]

See also

Notes

- ^ The office of Stewart Depute was also known as Sheriff Depute.[18]

- ^ Traditionalists were scathing of these new farming practices which they dismissed as fashionable rather than practical. Captain James Sutherland referred to Balfour’s attempts to grow sown grass as “awkward and feeble” and described his turnip crop as “pitiful”.[21]

- ^ 116,664 acres (47,212.2 ha) of farmland (90% of the archipelago's cultivated land excluding rough grazing) is now under grass, of which 40,668 acres (16,457.8 ha) are cut for hay or silage.[38]

- ^ This was by no means Balfour's only contribution to Orkney architecture; he owned Maes Howe on the Orkney Mainland, and paid for the construction of a protective roof which still exists today.[64]

References

- ^ "Map of Scotland in Scots – Guide and gazetteer" (PDF). Centre for the Scots Leid. Retrieved 27 December 2023.

- ^ a b Area and population ranks: there are c. 300 islands over 20 ha in extent and 93 permanently inhabited islands were listed in the 2011 census.

- ^ a b c National Records of Scotland (15 August 2013). "Appendix 2: Population and households on Scotland's Inhabited Islands" (PDF). Statistical Bulletin: 2011 Census: First Results on Population and Household Estimates for Scotland Release 1C (Part Two) (PDF) (Report). SG/2013/126. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Haswell-Smith (2004), pp. 364–367

- ^ a b "Orkney Placenames" Archived 30 August 2000 at the Wayback Machine Orkneyjar. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- ^ a b c d e Ordnance Survey. OS Maps Online (Map). 1:25,000. Leisure.

- ^ Anderson, Joseph (Ed.) (1893) Orkneyinga Saga. Translated by Jón A. Hjaltalin and Gilbert Goudie. Edinburgh. James Thin and Mercat Press (1990 reprint). ISBN 0-901824-25-9

- ^ Pedersen, Roy (January 1992) Orkneyjar ok Katanes. (Map) Nevis Print. Inverness.

- ^ Stewart, Walter (mid-1640s) "New Chorographic Description of the Orkneys" in Irvine (2006) p. 13. Translated from the original Latin by Ian Cunningham.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Tait (2006), pp. 498–507

- ^ Thomson (2001) p. 5

- ^

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Pont, Timothy". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Pont, Timothy". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- ^ Chambers, Robert (1874–1975). Biographical dictionary of eminent Scotsmen. Glasgow: Blackie & Son.

- ^ a b Stewart, Walter (mid-1640s) "New Chorographic Description of the Orkneys" in Irvine (2006) p. 23. Translated from the original Latin by Ian Cunningham.

- ^ John Maitland Thomson, Register of the Privy Seal of Scotland, 1634-1651 (Edinburgh, 1897), p. 501 no. 1344.

- ^ “Shapinsay, Balfour Castle” Canmore. Retrieved 30 December 2023.

- ^ Irvine, James M. "The New Descriptions of the Orkneys and Schetland: Introduction." in Irvine (2006) p. 11.

- ^ "The Pundlar Process". Fea, a genealogy with connections to Orkney, Scotland. Northern-skies.net. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- ^ a b Thomson (2001) p. 339

- ^ a b Thomson (2001) pp. 339-41

- ^ a b Thomson (2001) p. 341

- ^ a b Thomson, William P.L. "Agricultural Improvement" in Omand (2003), p. 98

- ^ Thomson (2001) p. 386

- ^ Thomson (2001) pp. 347, 383

- ^ Thomson (2001) p. 343

- ^ See for example Wightman, Andy (2015) The Poor Had No Lawyers. Edinburgh:Birlinn.

- ^ Thomson (2001) p. 400

- ^ Thomson (2001) pp. 401, 403

- ^ a b Miller, Ronald, ed. (1985). "The County of Orkney". The Third Statistical Account of Scotland. 20 (1). Scottish Academic Press: 181.

- ^ a b Glendinning, Miles; MacInnes, Ranald; MacKechnie, A. (1996). A History of Scottish Architecture: From the Renaissance to the Present Day. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 277–278. ISBN 9780748608492.

- ^ Thomson (2001) p. 402

- ^ Wickham-Jones, Caroline (2007) Orkney: A Historical Guide. Edinburgh. Birlinn. Page 193.

- ^ Thomson (2001) pp. 369-70

- ^ Fenton, Alexander (1997). The Northern Isles. East Linton: John Donald.

- ^ a b Thomson (2001) pp. 360, 362, 369

- ^ "North Isles and beyond Wreck Database" Scapa Flow Charters. Retrieved 13 October 2007

- ^ Thomson (2001) p. 420

- ^ Thomson (2001), p. 422

- ^ Thomson (2001) p. 431

- ^ a b c Smith, Robin (2001) The Making of Scotland. Edinburgh: Canongate.

- ^ a b Hewitson, Jim "The North Isles", in Omand (2003), p. 186

- ^ a b "Island Explorations—Shapinsay". The Orkney Website. Archived from the original on 9 October 2007. Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- ^ "Orkney storm beach". Orkney Landscapes. Fettes College. Archived from the original on 8 July 2007. Retrieved 12 October 2007.

- ^ "Voes, Ayres and Beaches" Archived 6 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine Scottish Natural Heritage. Retrieved 12 October 2007.

- ^ "Shapinsay". VisitOrkney. Archived from the original on 14 October 2007. Retrieved 12 October 2007.

- ^ McKirdy, Alan Gordon, John & Crofts, Roger (2007) Land of Mountain and Flood: The Geology and Landforms of Scotland. Edinburgh: Birlinn.

- ^ Brown, John Flett, "Geology and Landscape" in Omand (2003), pp. 4–5

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 279.

- ^ "Mill Dam, Shapinsay: Star Species" RSPB. Retrieved 12 October 2007.

- ^ "RSPB Bird Reports" Archived 6 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine Visitorkney.com. Retrieved 12 October 2007.

- ^ a b "Shapinsay" The Orcadian. Retrieved 12 October 2007. Archived 7 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Mill Dam RSPB Reserve". Shapinsay Development Trust. Retrieved 12 December 2023.

- ^ "Holm of Burghlee". Protected Planet. Retrieved 12 December 2023.

- ^ "New effort in Caithness to save great yellow bumblebee". 19 May 2014. BBC News. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- ^ Brown, John Flett "Geology and Landscape" in Omand (2003), p. 19

- ^ a b "Shapinsay" orkney.org. Retrieved 12 October 2007. Archived 9 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Lichens Species Action Plan" (pdf) Stirling Council. Retrieved 13 October 2007 Archived 8 September 2004 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ General Register Office for Scotland (28 November 2003) Scotland's Census 2001 – Occasional Paper No 10: Statistics for Inhabited Islands. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- ^ 1798, 1841, 1931 and 1961–2000: Haswell-Smith (2004), p. 364; for 1851–61 and related pages for 1871–1901L "A Vision of Britain Through Time" visionofbritain.org.uk. Retrieved 17 October 2007.

- ^ "Scotland's 2011 census: Island living on the rise". BBC News. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- ^ "Shapinsay Inhabited Island". General Register Office for Scotland. Archived from the original (Microsoft Excel spreadsheets) on 19 May 2011. Retrieved 2 November 2007.

- ^ "Balfour Castle Feature Page". Undiscovered Scotland. Retrieved 13 August 2007.

- ^ “The Douche”. Shapinsay Development Trust. Retrieved 12 December 2023.

- ^ a b "Burroughston Broch Feature Page". Undiscovered Scotland. Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- ^ Hogan, C. Michael (7 October 2007). Burroughston Broch. The Megalithic Portal. ed Andy Burnham. Retrieved 3 November 2007.

- ^ Wenham, Sheena "The South Isles" in Omand (2003), p. 98

- ^ "Agricultural Association". Shapinsay Development Trust. Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ^ "Shapinsay Renewables Ltd". Shapinsay Development Trust. October 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ^ "Shapinsay is positive about the future". Orkney Today. 20 September 2007. Retrieved 12 October 2007.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Shapinsay Renewables Ltd.". Companies House. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ "Island hotel gets funds for community buyout". BBC News. 8 December 2022. Retrieved 3 December 2023.

- ^ "Grants for projects across Scotland from Scottish Land Fund". North Edinburgh News. 14 December 2023. Retrieved 27 December 2023.

- ^ Stewart, Andrew (15 June 2023). "Shapinsay's only cafe reopens following development trust purchase". Press and Journal. Aberdeen. Retrieved 3 December 2023.

- ^ "Orkney Isles Preserves". Orkney.Com. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ "Balfour Castle – Orkney" balfourcastle.co.uk. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- ^ "Shapinsay salmon farm expansion". Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ^ "Shapinsay" (pdf) Orkney Ferries. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- ^ “Klydon”. Ships Nostalgia. Retrieved 3 December 2023.

- ^ “Clytus”. Ships Nostalgia. Retrieved 3 December 2023.

- ^ Muir, Tom "Transport and Communications" in Omand (2003), pp. 216, 219

- ^ “Shapinsay Ferry”. Undiscovered Scotland. Retrieved 3 December 2023.

- ^ Orkney to get two electric ferries for three-year trial BBC News Website, 11 September 2023. Retrieved 3 December 2023.

- ^ "Isle tunnel plans under spotlight". BBC News Website, 9 March 2005. Retrieved 18 October 2007.

- ^ "Electric Bikes". Shapinsay Development Trust. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ "Electric Cars". Shapinsay Development Trust. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ Shapinsay Community School Standards and Quality Report 2022-23 and School Improvement Plan 2023-24. (2023) Orkney Islands Council. p. 4

- ^ "Learning centre unit". UHI Millennium Institute. Archived from the original on 8 August 2007. Retrieved 12 October 2007.

- ^ "A 544-mile long nativity cracker". BBC news website. 14 December 2006. Retrieved 12 October 2007.

- ^ "Grinder Skole". Shapinsay Community School & Nursery. Archived from the original on 15 September 2007. Retrieved 8 December 2007.

- ^ For example, the children designed an owl that fits over light switches, reminding people to turn out lights. "When the lights go out on Shapinsay". Highlands and Islands Enterprise. 22 February 2007. Retrieved 12 October 2007.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Let's talk Renewables, Spring 2007" (PDF). Highlands and Islands Enterprise. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2008. Retrieved 12 October 2007.

- ^ "Shapinsay Primary School". Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Education. Archived from the original on 1 October 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

- ^ "Orkney's Giant Folklore" Orkneyjar. Retrieved 14 October 2007.

- ^ "Monsters of the Deep—The 1905 Shapinsay Sea Serpent". Orkneyjar. Retrieved 12 November 2007.

Bibliography

- Haswell-Smith, Hamish (2004). The Scottish Islands. Edinburgh: Canongate. pp. 364–367. ISBN 978-0-86241-579-2.

- Irvine, James M. (ed.) (2006) The Orkneys and Schetland in Blaeu's Atlas Novus of 1654. Ashtead. James M. Irvine. ISBN 0-9544571-2-9.

- Omand, Donald, ed. (2003). The Orkney Book. Edinburgh: Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-254-9.

- Tait, Charles (2006). "North Isles–Shapinsay" (PDF). Orkney Guide Book. Kirkwall: Charles Tait Photographic. pp. 498–507. ISBN 978-0-9517859-1-1.

- Thomson, William P. L. (2001). The New History of Orkney. Edinburgh: Mercat Press. ISBN 978-1-84183-022-3.

External links

- Shapinsay Development Trust

- Shapinsay Tourism Group Archived 20 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine