Theistic Satanism

Theistic Satanism, otherwise referred to as traditional Satanism, religious Satanism, or spiritual Satanism,[2] is an umbrella term for religious groups that consider Satan, the Devil, to objectively exist as a deity, supernatural entity, or spiritual being worthy of worship or reverence, whom individuals may believe in, contact, and convene with, in contrast to the atheistic archetype, metaphor, or symbol found in LaVeyan Satanism.[2][3][4]

Organizations who uphold theistic Satanist beliefs most often have few adherents, are loosely affiliated or constitute themselves as independent groups and cabals, which have largely self-marginalized.[5] Another prominent characteristic of theistic Satanism is the use of various types of magic.[2] Most theistic Satanist groups exist in relatively new models and ideologies, many of which are independent of the Abrahamic religions.[2][4][6]

In addition to the worship of Satan or the Devil in the Abrahamic sense, religious traditions based on the worship of other "adversarial" gods—usually borrowed from pre-Christian polytheistic religions—are often included within theistic Satanism.[2] Theistic Satanist organizations may incorporate beliefs and practices borrowed from Gnosticism, Hermeticism, Neo-Paganism, New Age, the left-hand path, black magic, ceremonial magic, Crowleyan magick, Western esotericism, occult traditions, and sorcery.[2][4][7]

Overview

Since the first half of the 1990s, the internet has increased the interaction, visibility, communication, and spread of different currents and beliefs among self-identified Satanists and has led to the propagation of more conflicting and diverse groups,[10] but Satanism has always been a heterogeneous, pluralistic, decentralized religious movement and "cultic milieu".[13] Religion academics, scholars of New religious movements, and sociologists of religion focused on Satanism have sought to study it by categorizing its currents according to whether they are esoteric/theistic or rationalist/atheistic,[14][15] and they referred to the practice of working with a literal Satan as theistic or "traditional" Satanism.[3] It is generally a prerequisite to being considered a theistic Satanist that the believer accepts a theological and metaphysical canon which involves one or more gods that are either considered to be Satan in the strictest, Abrahamic sense (the Judeo-Christian-Islamic conception of the Devil), or a conception of Satan that incorporates "adversarial" gods usually borrowed from pre-Christian polytheistic religions,[14] such as Ahriman or Enki.[16][17] Despite the number of self-professed theistic Satanists constantly increasing since the 1990s, they are considered by most scholars of religion to be a minority group within Satanism.[2][9]

Many theistic Satanists believe that their own individualized concepts are based on pieces of all of these diverse conceptions of Satan, according to their inclinations and sources of spiritual guidance, rather than only believing in one suggested interpretation.[2][4] Some may choose to live out the myths and stereotypes, but Christianity is not always the primary frame of reference for theistic Satanists.[2][4][6] Their religion may be based on Gnosticism, Hermeticism, Neo-Paganism, New Age, the left-hand path, black magic, ceremonial magic, Crowleyan magick, Western esotericism, occult traditions, and sorcery.[2][4][7] Theistic Satanists who base their faith on Christian ideas about Satan are referred to as "Diabolists",[18] although they are also referred to as "reverse Christians" by other Satanists, often in a pejorative fashion.[2][4] However, those labelled by some as "reverse Christians" may see their concept of Satan as undiluted or unsanitized. They worship a stricter interpretation of Satan: that of the Satan featured in the Christian Bible.[19] Peter H. Gilmore, current leader of the atheistic Church of Satan, considers "Devil-worship" to be a Christian heresy, that is, a divergent form of Christianity.[20] The diversity of individual beliefs within theistic Satanism, while being a cause for intense debates within the religion, is also often seen as a reflection of Satan, who is believed to encourage individualism.[21]

Recent and contemporary theistic Satanism

Currents

The diversity of beliefs amongst Satanists, both theistic and non-theistic, was examined in a demographic survey conducted in 2001 by the American religion scholar and sociologist of religion James R. Lewis and subsequently published in the Marburg Journal of Religion.[4] According to the survey, the statistically-average demographic and ideological profile of a Satanist is an unmarried White male raised as a Christian who began to explore other religions during his teenage years, upholds non-theistic humanism and practices magic.[4] A 2016 survey found that most self-identified Satanists were located in Denmark, Norway, and the United States.[22]

Our Lady of Endor Coven

The first recognized esoteric, non-LaVeyan Satanist organization was the Ophite Cultus Satanas,[23][24] which claimed to have been founded in 1948 by Herbert Arthur Sloane and therefore to allegedly precede the foundation of Anton LaVey's Church of Satan.[23][24] Their doctrine relies on a Gnostic conception of Satan as the liberating serpent and bestower of knowledge to humankind opposed to the malevolent demiurge or creator god,[23][24] mainly inspired by the Gnostic dualistic cosmology of the Ophites,[24] Hans Jonas' study on the history of Gnosticism,[23] and the writings of Margaret Murray on the witch-cult hypothesis.[23][24] "Our Lady of Endor" seems to have been the only existing coven of this Satanist organization,[24] which was disbanded shortly after the death of its founder during the 1980s.[23]

Temple of Set and Setianism

Some scholars equate the veneration of the Egyptian god Set by the Temple of Set to theistic Satanism.[3] However, other scholars do not consider them as theistic Satanists, and the affiliates to the Temple of Set themselves do not identify as such.[25] The doctrine of the Temple of Set, an occult initiatory order founded in 1975 by Michael Aquino as a splinter group from LaVey's Church of Satan, heavily relies on the writings of Aleister Crowley with elements borrowed from ceremonial magic, the left-hand path, Western esotericism, and mysticism.[25] They believe that the Egyptian deity Set is the real Prince of Darkness behind the name "Satan", of whom the Judeo-Christian-Islamic conception of the Devil is just a caricature.[25] Their practices primarily center on self-development.[25] Within the Temple of Set, the Black Flame of Set is the individual's god-like core which is a kindred spirit to Set, and which they seek to develop.[25] In theistic Satanism, the Black Flame is knowledge which was given to humanity by Satan, who is a being independent of the Satanist himself, and which he can dispense to the Satanist who seeks knowledge.[3] Religion scholar Kennet Granholm regards the Temple of Set as an occult organization that should not be labelled "Satanist" anymore, since it has cut all ties with the Satanic milieu and today entirely belongs to the left-hand path tradition.[26]

First Church of Satan

The First Church of Satan (FCoS), another splinter group that separated from LaVey's Church of Satan during the 1970s,[27] attempts to rediscover the teachings of Aleister Crowley and believe that Anton LaVey actually was a magus in the early days of the Church of Satan but gradually renounced his powers, became isolated and embittered.[27] Furthermore, the First Church of Satan strongly criticizes the current Church of Satan as a pale shadow of its former self, and they strive to "maintain a Satanic organization that is not hostile or manipulative toward its own members".[27]

Order of Nine Angles

The Order of Nine Angles (ONA or O9A) is a Satanic and left-hand path occultist group which is based in the United Kingdom, and associated groups are based in other parts of the world.[2][28][29] David Myatt,[29] a former bodyguard and supporter of the British Neo-Nazi leader Colin Jordan,[28][29] is considered the founder of the Order.[29] In 1998, Myatt converted to radical Islam while continuing to lead the Order of Nine Angles; later on, he repudiated the Islamic religion in 2010 and publicly declared to have renounced all forms of extremism.[29]

The Order of Nine Angles identify as theistic Satanists, practicing "traditional Satanism",[2] but observers have found a number of different occult and political beliefs.[29] Sociologist of religion Massimo Introvigne defined it as "a synthesis of three different currents: hermetic, pagan, and Satanist",[29] whereas the medievalist and professor of Religious studies Connell Monette dismissed the Satanic features of the O9A as "cosmetic" and contended that "its core mythos and cosmology are genuinely hermetic".[29] According to the scholar of Western esotericism Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke, "the ONA celebrated the dark, destructive side of life through anti-Christian, elitist, and Social Darwinist doctrines", together with the organization's implicit ties to Neo-Nazism and the appraisal of National Socialism.[28] The Order of Nine Angles believe that the seven planets and their satellites are connected to the "Dark Gods", while Satan is considered to be one of two "actual entities", the other one being Baphomet, with the former conceived as male and the latter as female.[29] The organization became controversial and was mentioned in the press and books because of their promotion of human sacrifice.[30] Since the 2010s, the political ideology and religious worldview of the Order of Nine Angles have increasingly influenced militant neo-fascist and Neo-Nazi insurgent groups associated with right-wing extremist and White supremacist international networks,[31] most notably the Iron March forum.[31] A number of rapes, killings and acts of terrorism have been perpetrated by individuals influenced by the O9A.[32]

Michael W. Ford

In Luciferianism, Michael W. Ford, author and black metal musician, abandoned the Order of Nine Angles in 1998, criticizing it for its Neo-Nazi ideology,[33] and founded his own autonomous Satanist organizations in the same year: the Order of Phosphorus[33] and the Black Order of the Dragon;[33] in the following years, he founded the Church of Adversarial Light in 2007,[33] and the Greater Church of Lucifer (GCOL) in 2013.[33] In 2015, Ford announced that the Order of Phosphorus would be integrated into the Greater Church of Lucifer, which welcomes both theistic and rationalistic Satanists, as well as Neo-Pagans and various followers of diverse occult spiritualities.[33] Ford presents both a theistic and atheistic approach to Luciferianism, and his ideas are enunciated in a wide compendium of publications,[33] although they are difficult to situate into a single, cohesive belief system;[33][34] the Wisdom of Eosphoros (2015) is considered the Greater Church of Lucifer's official statement and the core of its Luciferian philosophy.[33] Theistic Luciferianism is considered an individualistic, personal spirituality which is established via initiation and validation of the Adversarial philosophy. Luciferians, if theistic, do not accept the submission of 'worship' yet rather a unique and subjective type of Apotheosis via the energies of perceived deities, spirits and demons.

Joy of Satan

Joy of Satan Ministries (JoS), a website founded in the early 2000s by Maxine Dietrich (pseudonym of Andrea Herrington),[17][35] wife of the American National Socialist Movement's co-founder and former leader Clifford Herrington,[17][36][37] combines theistic Satanism with Neo-Nazism, racial anti-Semitism, anti-Judaic, anti-Christian sentiment and Gnostic Paganism, as well as Nordic aliens, UFO conspiracy theories and anti-Semitic conspiracy theories.[17][38] Joy of Satan advocates "spiritual Satanism" and believes Satan to be a sentient and powerful extraterrestrial being, although not a supernatural god.[17] The Satanic practices promoted by Joy of Satan involve meditation, telepathic contacts with demons, rituals, and sex magic.[17] In 2004, following the exposure of Andrea Herrington among Joy of Satan's members as the wife of Neo-Nazi leader Clifford Herrington and her ties with the National Socialist Movement, many adherents abandoned Joy of Satan and formed their own autonomous Satanist or Neo-Pagan organizations, such as the House of Enlightenment, Enki's Black Temple, the Siaion, the Knowledge of Satan Group, and the Temple of The Ancients.[17] According to Introvigne (2016), "most are by now defunct, while Joy of Satan continues its existence, although with a reduced number of members".[17] In July 2006, after the exposure of Herrington's wife's Satanic website within the National Socialist Movement, Andrea and Clifford Herrington were both kicked out of the National Socialist Movement;[36] following the Herrington scandal, Bill White, the then-National Socialist Movement's spokesman, also quit alongside many others.[36] According to Introvigne (2016), "its ideas on extraterrestrials, meditation, and telepathic contacts with demons became, however, popular in a larger milieu of non-LaVeyan "spiritual" or "theistic" Satanism".[17] According to the scholar of Religious studies and researcher of New religious movements Jesper Aagaard Petersen's survey on the Satanic milieu's proliferation on the internet (2014), "the only sites with some popularity are the Church of Satan and (somewhat paradoxically) Joy of Satan's page base on the angelfire network, and they are still very far from Scientology or YouTube. Most of these sites are decidedly fringe."[39]

Turku Society for the Spiritual Sciences

Pekka Siitoin founded the satanist group called the Turku Society for the Spiritual Sciences (Turun Hengentieteen Seura) on September 1, 1971. The society stated its founding principles as "promot[ing] nationalist patriotic activity [and] development of Aryan spirituality". The society also stated opposition to capitalism, communism and "the Jewish religion based on Jehovah's tyranny."[40] Siitoin believed in neo-Gnosticism and Theosophy and combined these with antisemitism and satanism. To him, Lucifer, Satan and Jesus were subordinate to the Monad, and could be worshiped together. According to Siitoin, Moses invented magic, but jealous Demiurge-Jehova seeks to obscure its knowledge from the gentiles. Lucifer was a Promethean figure who created the original humanity and granted them wisdom so that they would evolve to be equal to Gods in time, while Jehova created the Jewish race to usurp Lucifer's power and lord over humanity. Siitoin was also influenced by Christian apocrypha, like Gospel of Judas and to him Jesus was an agent of the Monad and Lucifer against the Demiurge. These are combined with elements of Finnish folk magic.[41][42][43][44] The society allegedly performed satanic orgies which researcher of religion Pekka Iitti opined might not be "far off from the truth".[45] Several of the perpetrators of the Kursiivi printing house arson in November 1977 were members of the society.[46][47]

Satanic Reds

Differing from other Satanic organizations, the Satanic Reds is an occult organization with a Marxist-Communist political orientation founded by Tani Jantsang in 1997.[48][49] Their doctrine is largely based on the writings of H. P. Lovecraft mixed with elements of Central Asian folklore and the advocacy of social welfare;[49] the group became notable mainly for their online activism and usage of communist symbols merged with Satanist ones.[49] However, the Satanic Reds claim to belong to the left-hand path but do not identify as theistic Satanists in the manner of believing in Satan as a god with a personality, since they conceive it as Sat and Tan, "Being and Becoming", similarly to the fictional deity of chaos Nyarlathotep from Lovecraft's Cthulhu Mythos.[49] The religious practices of the Satanic Reds comprise occult rituals and a form of baptism, and the organization advocates a "renewed New Deal", a moderate social program of reforms inspired by Franklin D. Roosevelt.[49]

Misanthropic Luciferian Order

One other group is the Temple of the Black Light, formerly known as the Misanthropic Luciferian Order prior to 2007. The group espouses a philosophy known as "Chaosophy". Chaosophy asserts that the world that mankind lives in, and the universe that it lives in, all exist within the realm known as Cosmos. Cosmos is made of three spatial dimensions and one linear time dimension. Cosmos rarely ever changes and is a materialistic realm. Another realm that exists is known as Chaos. Chaos exists outside of the Cosmos and is made of infinite dimensions and unlike the Cosmos, it is always changing. Members of the TotBL believe that the realm of Chaos is ruled over by 11 dark gods, the highest of them being Satan, and all of said gods are considered manifestations of a higher being. This higher being is known as Azerate, the Dragon Mother, and is all of the 11 gods united as one. The TotBL believes that Azerate will resurrect one day and destroy the Cosmos and let Chaos consume everything. The group has been connected to the Swedish black/death metal band Dissection, particularly its front man Jon Nödtveidt.[50] Nödtveidt was introduced to the group "at an early stage".[51] The lyrics on the band's third album, Reinkaos, are all about beliefs of the Temple of the Black Light.[52] Nödtveidt committed suicide in 2006.[53][54]

Other groups and currents

Some groups are mistaken by scholars for theistic Satanists, such as the First Church of Satan.[3] However, the founder of the FCoS, John Allee, considers what he calls "Devil-worship" to often be a symptom of psychosis. Other groups such as the 600 Club,[55] are accepting of all types of Satanists, as are the Synagogue of Satan, which aims for the ultimate destruction of all religions, paradoxically including itself, and encourages not self-indulgence but self-expression balanced by social responsibility.[56]

Relation to other theologies

Theistic Luciferian groups are particularly inspired by Lucifer (from the Latin for "bearer of light"), who they may or may not equate with Satan. While some theologians believe the Son of the Dawn, Lucifer, and other names were actually used to refer to contemporary political figures, such as a Babylonian King, rather than a single spiritual entity[57][58] (although on the surface the Bible explicitly refers to the King of Tyrus), those that believe it refers to Satan infer that by implication it also applies to the fall of Satan.[59] Satan is also identified by the Joy of Satan with the Sumerian god Enki and the Yazidi angel Melek Taus;[17] however, Introvigne (2016) himself remarks that their theistic Satanist interpretation of Enki derives from the writings of Zecharia Sitchin while the one about Melek Taus partially derives from the writings of Anton LaVey.[17]

Values in theistic Satanism

Seeking knowledge is seen by some theistic Satanists as being important to Satan, due to Satan being equated with the serpent in Genesis, which encouraged humans to partake of the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil.[61] Some perceive Satan as Éliphas Lévi's conception of Baphomet – a half-human and half-animal hermaphroditic bestower of knowledge (gnosis).[60] Some Satanic groups, such as Luciferians, also seek to gain greater gnosis.[50] Some of such Satanists, such as the former Ophite Cultus Satanas, equate Yahweh with the demiurge of Gnosticism, and Satan with the transcendent being beyond.[50]

Self-development is important to theistic Satanists. This is due to the Satanists' idea of Satan, who is seen to encourage individuality and freedom of thought, and the quest to raise one's self up despite resistance, through means such as magic and initiative. They believe Satan wants a more equal relationship with his followers than the Abrahamic god does with his. From a theistic Satanist perspective, the Abrahamic religions (chiefly Christianity) do not define "good" or "evil" in terms of benefit or harm to humanity, but rather on the submission to or rebellion against God.[62] Some Satanists seek to remove any means by which they are controlled or repressed by others and forced to follow the herd, and reject non-governmental authoritarianism.[63]

As Satan in the Old Testament tests people, theistic Satanists may believe that Satan sends them tests in life to develop them as individuals. They value taking responsibility for oneself. Despite the emphasis on self-development, some theistic Satanists believe that there is a will of Satan for the world and for their own lives. They may promise to help bring about the will of Satan,[64] and seek to gain insight about it through prayer, study, or magic. In the Bible, a being called "the god of this world" is mentioned in the Second Epistle to the Corinthians 4:4, which Christians typically equate with Satan.[65] Some Satanists therefore think that Satan can help them meet their worldly needs and desires if they pray or work magic. They would also have to do what they could in everyday life to achieve their goals, however.

Theistic Satanists may try not to project an image that reflects negatively on their religion as a whole and reinforces stereotypes, such as promoting Nazism, abuse, or crime.[63] However, some groups, such as the Order of Nine Angles, criticize the emphasis on promoting a good image for Satanism; the ONA described LaVeyan Satanism as "weak, deluded and American form of 'sham-Satanic groups, the poseurs'",[66] and ONA member Stephen Brown claimed that "the Temple of Set seems intent only on creating a 'good public impression', with promoting an 'image'".[67] The order emphasises that its way "is and is meant to be dangerous"[68] and "[g]enuine Satanists are dangerous people to know; associating with them is a risk".[69] Similarly, the Temple of the Black Light has criticized the Church of Satan, and has stated that the Temple of Set is "trying to make Setianism and the ruler of darkness, Set, into something accepted and harmless, this way attempting to become a 'big' religion, accepted and acknowledged by the rest of the Judaeo-Christian society".[50] The TotBL rejects Christianity, Judaism, and Islam as "the opposite of everything that strengthens the spirit, and is only good for killing what little that is beautiful, noble, and honorable in this filthy world".[50]

There is argument among Satanists over animal sacrifice, with most groups seeing it as both unnecessary and putting Satanism in a bad light, and distancing themselves from the few groups that practice it,[which?] such as the Temple of the Black Light.[70]

Theistic Satanism often involves a religious commitment, rather than being simply an occult practice based on dabbling or transient enjoyment of the rituals and magic involved.[71] Practitioners may choose to perform a self-dedication rite, although there are arguments over whether it is best to do this at the beginning of their time as a theistic Satanist, or once they have been practicing for some time.[72][53]

Historical mentions of Satanism

The age of accusations

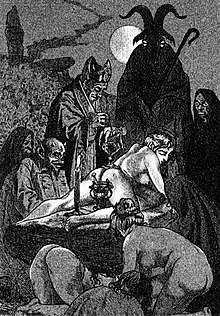

In the history of Christianity, the worship of Satan was a frequent accusation used since the Middle Ages.[73] The first ones formally accused to be Devil-worshippers were the Albigensians, a Gnostic Christian movement considered to be heretical and persecuted by the Roman Catholic Church; the charge was formulated during the Catholic Inquisition by the Fourth Lateran Council (1215), convoked by Pope Innocent III.[73] The charge of Devil-worship has also been made against groups or individuals regarded with suspicion, such as the Knights Templar or minority religions.[74] In the case of the trials of the Knights Templar (1307), the Templars' writings mentioned the term Baphomet, which was an Old French corruption of the name "Mahomet"[75] (the prophet of the people who the Templars fought against), and that Baphomet was falsely portrayed as a demon by the people who accused the Templars. During the Reformation Era, Counter-Reformation, and European wars of religion, the charge of Devil-worship was used against people charged in the witch trials in early modern Europe and other witch-hunts.[73] The most notorious cases were those of two German Inquisitors and Dominican priests under the patronage of Pope Innocent VIII: Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger, authors of the Malleus Maleficarum (1486),[2] in the Holy Roman Empire,[73] along with the Salem witch trials that occurred during the 17th-century Puritan colonization of North America.[73][76]

It is not known to what extent accusations of groups worshiping Satan in the time of the witch trials identified people who did consider themselves Satanists, rather than being the result of religious superstition or mass hysteria, or charges made against individuals suffering from mental illness. Confessions are unreliable, particularly as they were usually obtained under torture.[77] However, scholar Jeffrey Burton Russell, Professor Emeritus of the University of California at Santa Barbara, has made extensive arguments in his book Witchcraft in the Middle Ages that not all witch trial records can be dismissed and that there is in fact evidence linking witchcraft to Gnostic Christian heretical movements, particularly the antinomian sects.[78] Russell comes to this conclusion after having studied the source documents themselves. Individuals involved in the Affair of the Poisons were accused of Satanism and witchcraft.[79]

Historically, Satanist was a pejorative term for those with opinions that differed from predominant religious or moral beliefs.[80] Paul Tuitean believes the idea of acts of "reverse Christianity" was created by the Inquisition,[81] but George Bataille believes that inversions of Christian rituals such as the Mass may have existed prior to the descriptions of them which were obtained through the witchcraft trials.[82]

Grimoire Satanism

In the 1700s, various kinds of popular "Satanic" literature began to be produced in France, including some well-known grimoires with instructions for making a pact with the Devil. Most notable are the Grimorium Verum and The Grand Grimoire. The Marquis de Sade describes defiling crucifixes and other holy objects, and in his novel Justine he gives a fictional account of the Black Mass,[83] although Ronald Hayman has said Sade's need for blasphemy was an emotional reaction and rebellion from which Sade moved on, seeking to develop a more reasoned atheistic philosophy.[84] Nineteenth century occultist Éliphas Lévi published his well-known drawing of the Baphomet in 1855, which notably continues to influence Satanists today.

Finally, in 1891, Joris-Karl Huysmans published his Satanic novel, Là-bas, which included a detailed description of a Black Mass which he may have known firsthand was being performed in Paris at the time,[85] or the account may have been based on the masses carried out by Étienne Guibourg, rather than by Huysmans attending himself.[86] Quotations from Huysmans' Black Mass are also used in some Satanic rituals to this day, since it is one of the few sources that purports to describe the words used in a Black Mass. The type of Satanism described in Là-bas suggests that prayers are said to the Devil, hosts are stolen from the Catholic Church, and sexual acts are combined with Roman Catholic altar objects and rituals, to produce a variety of Satanism which exalts Satan and degrades the god of Christianity by inverting Roman Catholic rites. George Bataille claims that Huysman's description of the Black Mass is "indisputably authentic".[82] Not all theistic Satanists today routinely perform the Black Mass, possibly because the Mass is not a part of modern evangelical Christianity in Protestant-majority countries,[73] and so not such an unintentional influence on Satanist practices in those countries.

Organized Satanism

The earliest verifiable theistic Satanist group was a small group called the Ophite Cultus Satanas, which was created in Ohio in 1948. The Ophite Cultus Satanas was inspired by the ancient Ophite sect of Gnosticism, and the Horned God of Wicca. The group was dependent upon its founder and leader, and therefore dissolved after his death in 1975.

Michael Aquino published a rare 1970 text of a Church of Satan Black Mass, the Missa Solemnis, in his book The Church of Satan,[87] and Anton LaVey included a different Church of Satan Black Mass, the Messe Noire, in his 1972 book The Satanic Rituals. LaVey's books on Satanism, which began in the 1960s, were for a long time the few available which advertised themselves as being Satanic, although others detailed the history of witchcraft and Satanism, such as The Black Arts by Richard Cavendish published in 1967 and the classic French work Satanism and Witchcraft, by Jules Michelet. Anton LaVey specifically denounced "devil-worshippers" and the idea of praying to Satan.

Although non-theistic LaVeyan Satanism had been popular since the publication of The Satanic Bible in 1969, theistic Satanism did not start to gain any popularity until the emergence of the Order of Nine Angles in western England, and its publication of The Black Book of Satan in 1984.[88] The next theistic Satanist group to be created was the Misanthropic Luciferian Order, which was created in Sweden in 1995. The MLO incorporated elements from the Order of Nine Angles, the Illuminates of Thanateros, and qlippothic Qabalah.

The Dakhma of Angra Mainyu (Church of Ahriman), founded in 2012, is a theistic Satanist organization led by Adam Daniels.[89] Its worship includes celebrations of a Black Mass that involve desecration of consecrated hosts that are used in Christian celebrations of Holy Communion.[90][91][92] The Church of Ahriman performs rituals that involve the desecration of Christian statuary of the Virgin Mary using menstrual blood (which they refer to as "The Consumption of Mary"), as well as desecration of religious texts such as the Qur'an.[93][94] The Dakhma of Angra Mainyu performs Satanic exorcisms, an inversion of Christian exorcisms.[90]

Satan

Satan is a sinful entity depicted as the embodiment of evil in the Abrahamic religions. In Judaism, Satan is seen as an agent subservient to God, typically regarded as a metaphor for the yetzer hara, or "evil inclination." In Christianity and Islam, he is usually seen as a fallen angel or jinn who has rebelled against God, who nevertheless allows him temporary power over the fallen world and a host of demons.

Devil in Christianity

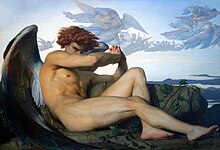

A large percentage of theistic Satanists worship Satan conceived as the Devil in the Christian religion.[2][3][4] In Christianity, the Devil, also known as Satan or Lucifer, is the personification of evil and author of sin, who rebelled against God in an attempt to become equal to God himself.[a] He is depicted as a fallen angel, who was expelled from Heaven at the beginning of time, before God created the material world, and is in constant opposition to God.[96][97]

The Devil is described and depicted as being perfect in beauty. He was so enamored with his own beauty and self, that he became vain, and so prideful[98] that he corrupted himself[99] and began to desire the same honor and glory that belonged to God. Eventually he rebelled and tried to overthrow God, and as a result was cast out of heaven.[100] Satan is also portrayed as a father to his daughter, Sin, by the 17th-century English poet John Milton in Paradise Lost.[101]

Symbolism

Since the 19th century, various small religious groups have emerged that identify as Satanists or use Satanic iconography. The Satanist groups that appeared after the 1960s are widely diverse, but two major trends are theistic Satanism and atheistic Satanism.[102] Theistic Satanists venerate Satan as worthy of worship, viewing him not as omnipotent but rather as a patriarch. In contrast, atheistic Satanists regard Satan as a symbol of certain human traits.[103]

Baphomet, a deity allegedly worshipped by the Knights Templar,[104] frequently appears in Satanic symbolism, with usage based on claims that Freemasonry worshipped both Satan and Baphomet, as well as Lucifer, in their rituals. Both Satan and Baphomet are often depicted or symbolized as a goat, therefore the goat and goat's head are significant symbols throughout Satanism. The inverted pentagram is also a significant symbol used for Satanism, sometimes depicted with the goat's head of Baphomet within it, popularized by the Church of Satan. In most recent and modern times the "inverted cross" is used and seen as an anti-Christian and satanic symbol, used similarly in the way of the inverted pentagram.[105]

Personal theistic Satanism

The American serial killer Richard Ramirez claimed that he was a (theistic) Satanist; during his 1980s killing spree he left an inverted pentagram at the scene of each murder and at his trial called out "Hail Satan!"[106] Ramirez made various references to Satan during his legal proceedings; he notably drew a pentagram on his palm at his trial.[107] Ramirez stated during his death row interview he believed in a "malevolent being" and that Satan's "description eludes" him.[108] Ramirez also enjoyed frequently degrading and humiliating his victims, especially those who survived his attacks or whom he explicitly decided not to kill, by forcing them to profess that they loved Satan, or telling them to "swear on Satan" if there were no more valuables left in their homes he had broken into and burglarized.

Modern-day public image of Satanism and moral panics

As a moral panic between the 1980s and the 1990s in the United States and Canada, there were multiple allegations of sexual abuse and/or ritual sacrifice of children or non-consenting adults in the context of Satanic rituals in what has come to be known as the Satanic Panic.[2][73][109][110]

Allegations included the existence of a worldwide Satanic conspiracy formed by large networks of organized Satanists involved in criminal activities such as murder, child pornography, sexual exploitation of children, and human trafficking for prostitution.[2][73][109] In the United States, the Kern County child abuse cases, McMartin preschool trial, and the West Memphis cases were widely reported.[109] One case took place in Jordan, Minnesota, in which children made allegations of the manufacture of child pornography, ritualistic animal sacrifice, coprophagia, urophagia, and infanticide, at which point the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) was alerted. Twenty-four adults were arrested and charged with acts of sexual abuse, child pornography, and other crimes claimed to be related to Satanic ritual abuse; three went to trial, two were acquitted, and one was convicted. Supreme Court Justice Scalia noted in a discussion of the case that "[t]here is no doubt that some sexual abuse took place in Jordan; but there is no reason to believe it was as widespread as charged", and cited the repeated, coercive techniques used by the investigators as damaging to the investigation.[111]

These notorious cases were launched after children were repeatedly and coercively interrogated by social workers, resulting in false allegations of child sexual abuse.[2][109] No evidence was ever found to support any of the allegations of an organized Satanist conspiracy or Satanic ritual abuses,[2][109] but in some cases the Satanic Panic resulted in wrongful prosecutions.[109] However, the National Center on Child Abuse and Neglect conducted a study led by University of California psychologist Gail Goodman did find "convincing evidence of lone perpetrators or couples who say they are involved with Satan or use the claim to intimidate victims."[112] One such case Goodman studied involved "grandparents [who] had black robes, candles, and Christ on an inverted crucifix--and the children had chlamydia, a sexually transmitted disease, in their throats", according to the report by a district attorney.[112]

In 2025, members of the Satanist group 764 were arrested for "blackmailing children—mainly girls—into carrying out sexual acts, harming themselves or even attempting suicide."[113] An investigation by the BBC found that members of this Satanic cult "seek out vulnerable young girls on social media, often in communities dedicated to self-harm or mental health."[113] Anti-terror police have stated that the Satanist network 764 poses "an immense threat" that is "not just within the United Kingdom but globally".[113]

See also

Notes

References

- ^ Petersen 2004, pp. 444–446.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Abrams, Joe (Spring 2006). Wyman, Kelly (ed.). "The Religious Movements Homepage Project – Satanism: An Introduction". virginia.edu. University of Virginia. Archived from the original on 29 August 2006. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Partridge 2004, p. 82.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Lewis, James R. (August 2001b). "Who Serves Satan? A Demographic and Ideological Profile". Marburg Journal of Religion. 6 (2). University of Marburg: 1–25. doi:10.17192/mjr.2001.6.3748. ISSN 1612-2941. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ Holt & Petersen 2016, pp. 447–448.

- ^ a b Petersen 2004, pp. 424–427, 442–443.

- ^ a b Petersen 2004, pp. 424–427.

- ^ a b Petersen 2004, pp. 429, 437.

- ^ a b Introvigne 2016, pp. 525–527.

- ^ [2][4][8][9]

- ^ Holt & Petersen 2016, pp. 441–452.

- ^ Petersen 2014, pp. 136–141.

- ^ [4][8][11][12]

- ^ a b Holt & Petersen 2016, pp. 450–452.

- ^ Gallagher 2004, p. 190.

- ^ Petersen 2004, p. 438.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Introvigne 2016, pp. 370–371.

- ^ "Is Theistic and Spiritual Satanism Just Reverse Christianity?". 10 November 2017.

- ^ Archived Cathedral of the Black Goat 'Views' Page

- ^ High Priest, Magus Peter H. Gilmore. "Satanism: The Feared Religion". churchofsatan.com.

- ^ Susej, Tsirk (2007). The Demonic Bible. Lulu.com. p. 11. ISBN 9781411690738. Retrieved 12 May 2008.

- ^ Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, pp. 164–165.

- ^ a b c d e f Lewis 2001a, p. 96.

- ^ a b c d e f Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, pp. 49–50.

- ^ a b c d e Petersen 2004, p. 436.

- ^ Introvigne 2016, pp. 355–356.

- ^ a b c Lewis 2001a, p. 91.

- ^ a b c Goodrick-Clarke, Nicholas (2001). "Nazi Satanism and The New Aeon". Black Sun: Aryan Cults, Esoteric Nazism, and the Politics of Identity. New York City: New York University Press. pp. 215–223. ISBN 978-0-8147-3124-6. LCCN 2001004429.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Introvigne 2016, pp. 358–364.

- ^ Lewis 2001a, p. 234.

- ^ a b Upchurch, H. E. (22 December 2021). Cruickshank, Paul; Hummel, Kristina (eds.). "The Iron March Forum and the Evolution of the "Skull Mask" Neo-Fascist Network" (PDF). CTC Sentinel. 14 (10). West Point, New York: Combating Terrorism Center: 27–37. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

The Order of Nine Angles and Terrorist Radicalization: The skull mask network's transformation into a clandestine terrorist network coincided temporally with the introduction of the Order of Nine Angles (O9A) worldview into the groups' ideological influences. The O9A is a occultist currentn founded by David Myatt in the late 1960s in the United Kingdom. The O9A shares with other pagan neo-fascists a belief in a primordial spirituality that has been supplanted by the Abrahamic faiths. Its doctrines are apocalyptic, predicting a final confrontation between monotheistic "Magian" civilization and primordial "Faustian" European spirituality. The skull mask network groups are not religiously monolithic, and most accept members who are not O9A adherents, but O9A philosophy has had a strong influence on the culture of the network. The O9A texts emphasize solitary rituals and the sense of membership in a superhuman spiritual elite. The O9A texts do not make social or financial demands on new adherents. Psychological commitment is instead generated through secrecy and the challenging, sometimes criminal, nature of the initiatory and devotional rituals. Because the rituals are solitary and self-administered, they create a set of shared 'transcendent' experiences that enhance group cohesion without the need for members to be geographically close to each other. Its leaderless structure and self-administered initiations make the O9A worldview uniquely well-suited to spread through online social networks, while the ritual violence used in O9A religious ceremonies contributed to the habituation of individual skull mask network members to violence.

- ^ "The Order of Nine Angles". Institute for Strategic Dialogue. 5 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Introvigne 2016, pp. 506–508.

- ^ Faxneld & Petersen 2013, p. 246.

- ^ Petersen 2014, p. 142.

- ^ a b c

• Zaitchik, Alexander (19 October 2006). "The National Socialist Movement Implodes". SPLCenter.org. Montgomery, Alabama: Southern Poverty Law Center. Archived from the original on 19 September 2015. Retrieved 28 December 2020.The party's problems began last June, when Citizens Against Hate discovered that NSM's Tulsa post office box was shared by The Joy of Satan Ministry, in which the wife of NSM chairman emeritus Clifford Herrington is High Priestess. [...] Within NSM ranks, meanwhile, a bitter debate was sparked over the propriety of Herrington's Joy of Satan connections. [...] Schoep moved ahead with damage-control operations by nudging chairman emeritus Herrington from his position under the cover of "attending to personal matters." But it was too late to stop NSM Minister of Radio and Information Michael Blevins, aka Vonbluvens, from following White out of the party, citing disgust with Herrington's Joy of Satan ties. "Satanism," declared Blevins in his resignation letter, "affects the whole prime directive guiding the [NSM] – SURVIVAL OF THE WHITE RACE." [...] NSM was now a Noticeably Smaller Movement, one trailed in extremist circles by a strong whiff of Satanism and related charges of sexual impropriety associated with Joy of Satan initiation rites and curiously strong teen recruitment efforts.

• "National Socialist Movement". SPLCenter.org. Montgomery, Alabama: Southern Poverty Law Center. 2020. Archived from the original on 8 September 2015. Retrieved 28 December 2020.The NSM has had its share of movement scandal. In July 2006, it was rocked by revelations that co-founder and chairman emeritus Cliff Herrington's wife was the "High Priestess" of the Joy of Satan Ministry, and that her satanic church shared an address with the Tulsa, Okla., NSM chapter. The exposure of Herrington's wife's Satanist connections caused quite a stir, particularly among those NSM members who adhered to a racist (and heretical) variant of Christianity, Christian Identity. Before the dust settled, both Herringtons were forced out of NSM. Bill White, the neo-Nazi group's energetic spokesman, also quit, taking several NSM officials with him to create a new group, the American National Socialist Workers Party.

- ^ "The National Socialist Movement". Adl.org. New York City: Anti-Defamation League. 2020. Archived from the original on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ "Satanism – Founders, Philosophies & Branches". History.com. A&E Networks. 27 September 2019. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ Petersen 2014, pp. 144–146.

- ^ Häkkinen, Perttu; Iitti, Vesa (2022). Lightbringers of the North: Secrets of the Occult Tradition of Finland. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-64411-464-3. p. 133

- ^ Western Esotericism in Scandinavia, 2016, p. 326-328. Edited by Henrik Bogdan and Olav Hammer.

- ^ Granholm, Kennet. “‘Worshipping the Devil in the Name of God’: Anti-Semitism, Teosophy and Christianity in the Occult Doctrines of Pekka Siitoin.” Journal for the Academic Study of Magic, no. 5 (2009): 256–286.

- ^ Pasanen, T. (2021). Christus verus Luciferus, Demon est Deus Inversus: Pekka Siitoin’s Spiritism Board. Temenos - Nordic Journal for the Study of Religion, 57(2), 181–207. https://doi.org/10.33356/temenos.107763

- ^ Keronen, Jiri: Pekka Siitoin teoriassa ja käytännössä. Helsinki: Kiuas Kustannus, 2020. ISBN 978-952-7197-21-9

- ^ Häkkinen, Iitti 2022 pp.142

- ^ "Pekka Siitoin Was the New Face of Neo-Fascism in Finland [in Finnish]". Finnish Broadcasting Company. 4 May 2015. Archived from the original on 6 May 2015. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- ^ Häkkinen, Iitti 2022 p. 137, 142

- ^ Lewis 2001a, p. 240.

- ^ a b c d e Introvigne 2016, pp. 523–525.

- ^ a b c d e "Interview_MLO". Angelfire.com. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ "Dissection. Interview with Jon Nödtveidt. June 2003". Metal Centre. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ "Official Dissection Website :: Reinkaos". Dissection.nu. Archived from the original on 8 February 2008.

- ^ a b "Dissection Frontman Jon Nödtveidt Commits Suicide". Metal Storm. 18 August 2006. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ "Dissection Guitarist: Jon Nödtveidt Didn't Have Copy of 'The Satanic Bible' at Suicide Scene". Blabbermouth. 23 August 2006. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ Petersen 2004, p. 429.

- ^ Mathews 2009, p. 92.

- ^ "Lucifer King Of Babylon". realdevil.info.

- ^ "Satan, Devil and Demons – Isaiah 14:12–14". www.wrestedscriptures.com.

- ^ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Devil". newadvent.org.

- ^ a b Strube, Julian (2016). "The 'Baphomet' of Èliphas Lévi: Its Meaning and Historical Context" (PDF). Correspondences: An Online Journal for the Academic Study of Western Esotericism. 4: 37–79. ISSN 2053-7158. Archived from the original on 8 February 2017. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ^ Partridge 2004, p. 228.

- ^ "Elliot Rose on "Evil"". theisticsatanism.com.

- ^ a b Petersen 2004, pp. 446–447.

- ^ Mickaharic, Draja (1995). Practice of Magic: An Introductory Guide to the Art. Weiser. p. 62. ISBN 9780877288077. Retrieved 24 May 2008.

- ^ Ladd, George Eldon (1993). A Theology of the New Testament. Wm. B. Eerdmans. p. 333. ISBN 9780802806802. Retrieved 12 May 2008.

- ^ Commentary on Dreamers of the Dark Archived 24 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Stephen Brown: The Satanic Letters of Stephen Brown: St. Brown to Dr. Aquino (online version Archived 13 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine).

- ^ The True Way of the ONA Archived 2 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Satanism: The Epitome of Evil Archived 2 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Animal Sacrifice and the Law". theisticsatanism.com.

- ^ Partridge 2004, p. 83.

- ^ "Pacts and self-initiation". theisticsatanism.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Christiano, Kevin J.; Kivisto, Peter; Swatos, William H. Jr., eds. (2015) [2002]. "Boundary Issues: Church, State, and New Religions – "Satanism" and Anti-Satanism". Sociology of Religion: Contemporary Developments (3rd ed.). Walnut Creek, California: AltaMira Press. pp. 318–324. ISBN 978-1-4422-1691-4. LCCN 2001035412.

- ^ Klaits 1985, p. 25.

- ^ Stahuljak, Zrinka (2013). "Symbolic Archaeology". Pornographic Archaeology: Medicine, Medievalism, and the Invention of the French Nation. Philadelphia: De Gruyter/University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 71–82. doi:10.9783/9780812207316.71. ISBN 978-0-8122-4447-2. JSTOR j.ctt3fhd6c.7.

- ^ Klaits 1985, p. 2.

- ^ Klaits 1985, p. 11.

- ^ Russell 1972, pp. 133–198.

- ^ van Luijk 2016, pp. 45–56.

- ^ Behrendt, Stephen C. (1983). The Moment of Explosion: Blake and the Illustration of Milton. U of Nebraska Press. p. 437. ISBN 0803211694. Retrieved 6 June 2008.

- ^ Tuitean, Paul; Daniels, Estelle (1998). Pocket Guide to Wicca. The Crossing Press. p. 22. ISBN 9780895949042. Retrieved 5 June 2008.

- ^ a b Bataille, George (1986). Erotism: Death and Sensuality. Dalwood, Mary (trans.). City Lights. p. 126. ISBN 9780872861909. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- ^ Sade, Donatien (2006). The Complete Marquis De Sade. Holloway House. pp. 157–158. ISBN 9780870679407. Retrieved 22 May 2008.

- ^ Hayman, Ronald (2003). Marquis de Sade: The Genius of Passion. Tauris Parke. pp. 30–31. ISBN 9781860648946. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- ^ Huysmans, Joris-Karl (1972). La Bas. Keene Wallace (trans.). Courier Dover. back cover. ISBN 9780486228372. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- ^ Laver, James (1954). The First Decadent: Being the Strange Life of J.K. Huysmans. Faber and Faber. p. 121.

- ^ Aquino, Michael (2002). The Church of Satan., Appendix 7.

- ^ The Black Book of Satan. 1984, Thormynd Press, ISBN 0-946646-04-X. British Library General Reference Collection Cup.815/51, BNB GB8508400

- ^ Laycock, Joseph P. (20 January 2020). Speak of the Devil. Oxford University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-19-094850-4.

- ^ a b Keneally, Meghan (10 September 2014). "Satanists to Hold Controversial Black Mass in Oklahoma". ABC News.

- ^ Nicks, Denver (22 August 2014). "Oklahoma Catholics Drop Lawsuit After Satanists Return Wafer". Time Magazine.

- ^ "Okla. Christians counter Satanic mockery of Virgin Mary with prayer". Catholic News Agency. 11 August 2016.

- ^ "Christians Take a Different Approach to 'Protesting' Satanic Black Mass". CBN. 10 December 2022.

- ^ Luschen, Ben (29 June 2016). "Black Mass and The Consumption of Mary set for Aug. 15". Oklahoma Gazette.

- ^ Geisenhanslüke, Mein & Overthun 2015, p. 217.

- ^ McCurry, Jeffrey (2006). "Why the Devil Fell: A Lesson in Spiritual Theology From Aquinas's 'Summa Theologiae'". New Blackfriars. 87 (1010): 380–395. doi:10.1111/j.0028-4289.2006.00155.x. JSTOR 43251053.

- ^ Goetz 2016, p. 221.

- ^ "How Did Lucifer Fall and Become Satan?". Christianity.com. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ "What the Bible says about Satan's Pride". www.bibletools.org. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ This Provocative Painting Made Everyone Cringe. Here's Why., 31 August 2022, retrieved 16 September 2022

- ^ Flinker, Noam (December 1980). Jones, Edward (ed.). "Father-Daughter Incest in "Paradise Lost"". Milton Quarterly. 14 (4). Wiley: 116–122. doi:10.1111/j.1094-348X.1980.tb00305.x. ISSN 1094-348X. JSTOR 24463094.

- ^ Abrams, Joe (Spring 2006). Wyman, Kelly (ed.). "The Religious Movements Homepage Project - Satanism: An Introduction". virginia.edu. University of Virginia. Archived from the original on 29 August 2006. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- ^ Gilmore, Peter (10 August 2007). "Science and Satanism". Point of Inquiry Interview. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- ^ Stahuljak 2013, pp. 71–82.

- ^ "Upside Down Cross Meaning And Symbolism, The Petrine Cross". 4 July 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- ^ Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 122.

- ^ "Richard Ramirez | Biography, Night Stalker, Death, Childhood, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- ^ Death Row Interview With Night Stalker Richard Ramirez, 22 February 2020, retrieved 26 September 2022

- ^ a b c d e f van Luijk 2016, pp. 356–364.

- ^ Frankfurter, D (2006). Evil Incarnate: Rumors of Demonic Conspiracy and Ritual Abuse in History. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-11350-5.

- ^ Maryland v. Craig, 497 U.S. 836 (1990).

- ^ a b Goleman, Daniel (1994). "Proof Lacking for Ritual Abuse by Satanists". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ^ a b c Crawford, Angus; Smith, Tony (16 January 2025). "Child abuse terror warning as 'Satanist' teenager jailed". BBC. Retrieved 16 January 2025.

Bibliography

- Dyrendal, Asbjørn (2016). "Satanism in Norway". In Bogdan, Henrik; Hammer, Olav (eds.). Western Esotericism in Scandinavia. Brill Esotericism Reference Library. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. 481–488. doi:10.1163/9789004325968_062. ISBN 978-90-04-30241-9. ISSN 2468-3566. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Dyrendal, Asbjørn; Lewis, James R.; Petersen, Jesper Aagaard, eds. (2016). The Invention of Satanism. New York City: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-518110-4. LCCN 2015013150. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- Faxneld, Per; Petersen, Jesper Aagaard, eds. (2013). The Devil's Party: Satanism in Modernity. New York City: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-977923-9. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- Gallagher, Eugene V. (2004). "New Foundations". The New Religious Movements Experience in America. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 187–196. ISBN 0-313-32807-2. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Geisenhanslüke, Achim; Mein, Georg; Overthun, Rasmus (2015) [2009]. Geisenhanslüke, Achim; Mein, Georg (eds.). Monströse Ordnungen: Zur Typologie und Ästhetik des Anormalen [Monstrous Orders: On the Typology and Aesthetics of the Abnormal]. Literalität und Liminalität (in German). Vol. 12. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag. doi:10.1515/9783839412572. ISBN 978-3-8394-1257-2.

- Goetz, Hans-Werner (2016). Gott und die Welt. Religiöse Vorstellungen des frühen und hohen Mittelalters. Teil I, Band 3: IV. Die Geschöpfe: Engel, Teufel, Menschen [God and the world. Religious Concepts of the Early and High Middle Ages. Part I, Volume 3: IV. The Creatures: Angels, Devils, Humans] (in German). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-8470-0581-0.

- Holt, Cimminnee; Petersen, Jesper Aagaard (2016) [2008]. "Modern Religious Satanism: A Negotiation of Tensions". In Lewis, James R.; Tøllefsen, Inga (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of New Religious Movements, Volume 2 (2nd ed.). New York City: Oxford University Press. pp. 441–452. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190466176.013.33. ISBN 978-0-19-046617-6. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- Introvigne, Massimo (2016). Satanism: A Social History. Aries Book Series: Texts and Studies in Western Esotericism. Vol. 21. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-28828-7. OCLC 1030572947. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Klaits, Joseph (1985). Servants of Satan: The Age of the Witch Hunts. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-20422-4. JSTOR j.ctt16xwc16. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Lewis, James R. (2001a). Satanism Today: An Encyclopedia of Religion, Folklore, and Popular Culture. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-292-9. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Mathews, Chris (2009). Modern Satanism: Anatomy of a Radical Subculture. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-313-36639-0. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Moynihan, Michael; Søderlind, Didrik (2003) [1998]. Lords of Chaos: The Bloody Rise of the Satanic Metal Underground (Revised and expanded ed.). Port Townsend, Washington: Feral House. ISBN 0-922915-94-6.

- Partridge, Christopher (2004). The Re-Enchantment of the West: Alternative Spiritualities, Sacralization, Popular Culture, and Occulture. Vol. 1. London: T&T Clark. ISBN 0-567-08269-5. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Petersen, Jesper Aagaard (2004). "Modern Satanism: Dark Doctrines and Black Flames". In Lewis, James R.; Petersen, Jesper Aagaard (eds.). Controversial New Religions (1st ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/019515682X.003.0019. ISBN 978-0-19-515682-9.

- Petersen, Jesper Aagaard (2014). "From Book to Bit: Enacting Satanism Online". In Asprem, Egil; Granholm, Kennet (eds.). Contemporary Esotericism. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge. pp. 134–158. ISBN 978-1-908049-32-2. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Petersen, Jesper Aagaard, ed. (2016) [2009]. Contemporary Religious Satanism: A Critical Anthology. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7546-5286-1.

- Russell, Jeffrey Burton (1972). Witchcraft in the Middle Ages. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-0697-8. JSTOR 10.7591/j.ctvv416z0. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- van Luijk, Ruben (2016). Children of Lucifer: The Origins of Modern Religious Satanism. Oxford Studies in Western Esotericism. New York City: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-027512-9. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

Further reading

- Ellis, Bill, Raising the Devil: Satanism, New Religions, and the Media (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2000)

- Hertenstein, Mike; Jon Trott, Selling Satan: The Evangelical Media and the Mike Warnke Scandal (Chicago: Cornerstone Press, 1993)

- Introvigne, Massimo (13 April 2017). "Satan the Prophet: A History of Modern Satanism" (PDF). CESNUR. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 June 2017. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- Medway, Gareth J.; The Lure of the Sinister: The Unnatural History of Satanism (New York and London: New York University Press, 2001)

- Michelet, Jules, A. R. Allinson. Satanism and Witchcraft: The Classic Study of Medieval Superstition (1992), Barnes & Noble, 9780806500591

- Palermo, George B.; Michele C. Del Re: Satanism: Psychiatric and Legal Views (American Series in Behavioral Science and Law). Charles C Thomas Pub Ltd (November 1999)

- Richardson, James T.; Joel Best; David G. Bromley, The Satanism Scare (New York: Aldine de Gruyter, 1991)