Professional mourning

Professional mourning or paid mourning is an occupation that originates from Egyptian, Chinese, Mediterranean and Near Eastern cultures. Professional mourners, also called moirologists[1] and mutes, are compensated to lament or deliver a eulogy and help comfort and entertain the grieving family. Mentioned in the Bible[2] and other religious texts, the occupation is widely invoked and explored in literature, from the Ugaritic epics of early centuries BC[3] to modern poetry.

History

Most of the people hired to perform the act of professional mourning were women. Men were deemed unfit for this because they were supposed to be strong and leaders of the family, unwilling to show any sort of raw emotion like grief, which is why women were professional mourners. It was socially acceptable for women to express grief, and expressing grief is important when it comes to mourning a body in terms of religion.[4] Also, in a world full of jobs solely made for men, it gave women a sense of pride that they were actually able to earn money in some way.[4] Mourners were also seen as a sign of wealth. The more wailers or mourners that followed a casket around, the more respected the deceased was in society.[5]

Egypt

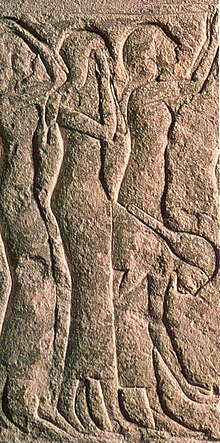

In ancient Egypt, the mourners would be making an ostentatious display of grief which included tearing at dishevelled hair, loud wailing, beating of exposed breasts, and smearing the body with dirt.[6] There are many inscriptions on tombs and pyramids of crowds of people following a body throughout the funerary procession.[5] However, the most important of these women were the two impersonating the two godddesses Isis and Nephthys.

Isis and Nephthys were both Egyptian goddesses who were believed to play a special role when someone died. They were to be impersonated as a mourning ritual by professional mourners. In most inscriptions seen, one of them is at either end of the corpse.[5] There are also rules for impersonation of these two goddesses, for example the portrayer's body had to be shaved completely, they had to be childless, and they had to have the names of Isis or Nephthys tattooed on their shoulders for identification.[5] Evidence of professional mourning is seen in Ancient Egypt through different pyramid and tomb inscriptions. Different inscriptions show women next to tombs holding their bodies in ways that show sorrow, such as "hands holding the backs of their necks, crossing their arms on their chests, kneeling and/or bending their bodies forwards".[7]

China

Professional mourners have been regular attendees of Chinese funerals since 756.[8] The tradition of professional mourning stemmed from theatrical performances that would occur during funerary processions.[8] There were musical performances at funerals as early as the third century. Scholar Jeehee Hong describes one such scene:

"they...set up wooden figures of Xiang Yu and Liu Bang participating in the banquet at Goose Gate. The show lasted quite some time." This performance was part of a funeral procession during the Dali reign (766–779) as the coffin of the deceased was being carried on the streets to his tomb site. The main funerary ritual had taken place at the house of the deceased, and now the mourners were walking in the funeral procession, along with a troupe of performers. The latter performance of this celebrated episode of the feast at the Goose Gate (Hongmen) from the Three Kingdoms saga was preceded by the enactment of a combat scene between two celebrated soldiers in history that was performed alongside the procession.[9]

Most of the historical evidence of mourning exists in the form of inscriptions on the different panels of tombs. Each slab contains a different story, and by the analysis of these inscriptions we are able to tell that these were played out during the funeral. For example:

Each scene—the preparation of food, the groom with a horse, and the entertainment – is unfailingly reminiscent of classical representations that adorn many tomb walls or coffin surfaces created since the Han period...these motifs are generally understood by students of Chinese funerary art as a banquet for the deceased...it is clear they represent the deceased couple because of the motif's strong connection to traditional representations of performances prepared for tomb occupants[10]

India

Female professional mourners, called rudaali, are common in many parts of India, especially in the Western Indian state of Rajasthan.[11]

Europe

In Roman history, mourners were hired to accompany funerary rituals and were often thought to be theatrical. In early history the public mourners, called praeficiae, would follow musicians in a funeral procession to sing for the dead.[12]

This tradition evolved from singing to wailing and became more a spectacle because it was seen as a sign of wealth if a funeral had wailers, the more money you had the more wailers you could afford. Funerals began posting decrees to exclude paid mourners as they would often scratch at their faces to injure themselves or making over-dismal wails that were often offensive to genuine mourners. For public mournings that travelled through the streets of a city, hired mourners would often trail behind wailing to alert the town of a death.

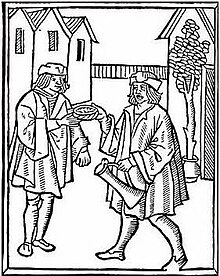

By the 16th-17th century, in areas throughout France and Britain, this evolved into what became a man's profession, and had more intention of alerting of a death so others could mourn rather than mourning for the public. When a person of distinction passed, a "Death Crier" or "Death Watch" would walk through a town shouting of the loss and quoting scripture. They wore long black cloaks with skull and cross-bone patterns and carried a bell.[13]

In the Bible

Professional mourning is brought up many times throughout the Bible. For example in Amos,

"Therefore thus says the LORD God of hosts, the Lord, "There is wailing in all the plazas, And in all the streets they say, 'Alas! Alas!' They also call the farmer to mourning And professional mourners to lamentation" (Amos 5:16).

According to Biblical analysts, this verse is implying that lamentation is like an art. People who were deemed "good" at wailing and moaning were then able to take part in more and more funerals, and were expected to make these moaning sounds.[14] The people who fulfilled the roles of these professional mourners were farmers who were done cropping for their season, and didn't have much else to do, so they took on this role for the extra money it would get them.[14]

Another instance of professional mourning worth noting is in Chronicles, the Bible says

"Then Jeremiah chanted a lament for Josiah. And all the male and female singers speak about Josiah in their lamentations to this day. And they made them an ordinance in Israel; behold, they are also written in the Lamentations." (2 Chronicles 35:25).

When someone of power dies, in this case Josiah, everyone can fill the role of mourner, professionals aren't needed because everyone feels the weight of the loss. Everyone becomes the professional mourner.

In the book of Jeremiah,

"Thus says the Lord of hosts, “Consider and call for the mourning women, that they may come; And send for the wailing women, that they may come! “Let them make haste and take up a wailing for us, That our eyes may shed tears and our eyelids flow with water" (Jeremiah 9: 17–18).

These three quotes from the Bible are just three of many that pertain to professional mourning.

Modern practice

China

Professional mourning is still practiced in China and other Asian countries. Chinese professional mourners in particular have survived dramatic cultural shifts such as the Cultural Revolution, though not without having to adjust to the times. For example, in an interview published in 2009, one professional mourner, who wailed and played the suona, recounted how, after the Proclamation of the People's Republic of China, he and his troupe began playing revolutionary songs like "The Sky in the Communist Regions Is Brighter" during funerals.[15] In fact, some cultures even think that the use of professional mourners brings a certain religious and historical application to funeral processions.[16]

A common ritual in China involves the family paying the mourners in advance and bringing them in lavish style to the location where the funeral will take place. The mourners are trained in the art of singing and bring a band with them.[17] The first step is for the mourners to line up outside and crawl.[16] While crawling, the mourner says with anguish the name of the person.[17] This is symbolic of daughters running home from their families in an effort to see the body. Next, a eulogy is performed in loud, sobbing fashion and backed up by dramatic instrumental tunes, driving the attendees to tears. One of the common lines used during these eulogies are "Why did you leave us so soon? The earth is covered in a black veil for you. The rivers and streams are crying to tell your story – that of an honest man...I shed tears for your children and grandchildren. We’re so sorry we could not keep you here"[citation needed]

Then the family is told to bow in front of the casket three times, and suddenly a belly dancer takes the so called "stage" and the song picks up, lights start flashing, and everyone is upbeat again. Since the funeral is usually a couple of days after the actual death, the goal of the professional mourner is to remind everyone attending the funeral about the sadness and pain that is associated with when someone passes away. They also have the job of bringing the mood right back up with lighting and fun songs after the wailing and mourning is done.[17]

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, a company called "Rent A Mourner" (now defunct[18]) enabled families to increase the number of guests at a funeral by hiring actors to play a role, for example, a distant cousin or uncle.[19] Mourners were expected to be able to interact with guests without giving away that they had been hired by the family. This practice spans across religions; mourners have been hired at Jewish and Christian events.[19] These mourners were paid somewhere between $30 - $120 per event, not including potential tips.[19]

Egypt

In Egypt, when someone in the family dies the women in the family would start the lamenting process, and the neighbors and the community would join throughout the day. Professional mourners would also come up and help lead the family in mourning by making grief-stricken shrieks, cherishing and reminiscing about the deceased. A funeral dirge is also performed by the mourners in which prayers are offered in the form of song or poetry.[20] One of the teachings of Muhammad was that the sound of wailing woman was forbidden, but modern Egyptian culture does not heed to this part of the Quran as the wailing and mourners follow the body to the graveyard.[20] All of this occurs within the same day, or if the deceased were to pass away in the night, the following day.[20]

In popular culture

Films

- The Italian mondo film Women of the World (1963) features a segment about professional mourning

- The British spy movie Funeral In Berlin (1966), directed by Guy Hamilton and starring Michael Caine, has a "mourner for hire" as part of the plot to exfiltrate a defector from East Berlin.[21]

- The Indian film Rudaali (1993), directed by Kalpana Lajmi and set in Rajasthan, is about the life of a professional mourner, or Rudaali.[22]

- The short documentary Tabaki (2001), directed by Bahman Kiarostami, follows the lives of "mourners for hire".[23]

- The Philippine film Crying Ladies (2003), directed by Mark Meily, follows the lives of three women who work as professional mourners, set in the Philippines.[24]

- The Japanese film Miewoharu (2016), directed by Akiyo Fujumura. It is centered around Eriko, a woman that comes back to her home town to mourn her sister. After spending 10 years in Tokyo pursuing an acting career she then discovers her vocation as professional mourner.[25]

Literature

- In Honoré de Balzac's landmark novel Le Père Goriot (1835), the title character's funeral is attended by two professional mourners rather than his daughters.[26]

- In E. M. Forster's novel Howards End (1910), for his wife's funeral, Charles Wilcox retains women to serve as mourners "from the dead woman's district, to whom black garments had been served out."[27]

- In Zakes Mda's novel Ways of Dying (1995), Toloki is a self-employed professional mourner.[28]

- In his 2014 novel Ghost Month, author Ed Lin states that professional mourners are available for hire in contemporary Taiwan.

- In Japanese manga artist Junji Ito's collection The Liminal Zone (2021), the first of the four one-shot stories revolves around a couple named Yuzuru and Mako which come in contact with professional mourners at a rural village.

Television

- In the episode "Grave Danger" of The Cleveland Show, the title character Cleveland Brown, along with his friends Lester, Holt, Tim the Bear, and Dr. Fist, temporarily become professional mourners and sit in on several funerals while spending time at Stoolbend Cemetery.

- In the episode "Death" in the travel documentary The Moaning of Life, host Karl Pilkington travels to Taiwan to train with a professional mourner and attends a memorial service.

- In the episode "The Princess" of Rita, Uffe suggest that Rita may need a professional mourner to help her grieve after the death of her mother.

- In the episode "Insufficient Praise" of Curb Your Enthusiasm, Richard's new girlfriend is a professional crier who places Larry in a number of predicaments.

- In an episode of Nathan For You, Nathan Fielder convinces a funeral home to hire professional mourners. Unbeknownst to them he hired random actors off the street. And a test run of it ended in disaster.

Music

- Hank Williams' song "Nobody's Lonesome for Me" contains the lyric, "When the time comes around for me to lay down and die, I bet I'll have to go and hire me someone to cry".

See also

- Claque, an organized body of professional applauders in France

- Grief

- Keening, a form of vocal lament associated with mourning that is traditional in Ireland, Scotland, and other cultures.

- Placebo (at funeral), someone who came to a funeral, claiming (often falsely) a connection with the deceased to try to get a share of any food and/or drink being handed out

- Funeral#Mutes and professional mourners

References

- ^ Orbey, Eren (January 20, 2021). "A Greek Photographer's Ode to the Dying Art of Mourning". New Yorker. Archived from the original on November 10, 2023. Retrieved November 10, 2023.

- ^ "Mourning: Hired Mourners". Bible Hub. Archived from the original on 2016-10-25. Retrieved 2016-10-23.

- ^ Angi, Betty Jean (October 1971). "THE UGARITIC CULT OF THE DEAD A STUDY OF SOME BELIEFS AND PRACTICES THAT PERTAIN TO THE UGARITIANS' TREATMENT OF THE DEAD" (PDF): 30/37. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Arbel, Vita (2012). Forming Femininity in Antiquity. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-19-983777-9.

- ^ a b c d "Requirements of Professional Mourners in Ancient Egypt. - María Rosa Valdesogo". María Rosa Valdesogo (in European Spanish). 2014-10-15. Archived from the original on 2018-04-29. Retrieved 2018-04-28.

- ^ Tyldesley, Joyce (March 30, 1995). Daughters of Isis:Women of Ancient Egypt. Penguin Books. p. 132. ISBN 9780141949819.

- ^ "Controlled Attitude of Professional Mourners in Ancient Egypt". María Rosa Valdesogo. April 25, 2016. Archived from the original on November 9, 2023. Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- ^ a b Hong, Jeehee (2016). Theater Of The Dead. University of Hawaii Press.

- ^ Hong, Jeehee (2016). Theater Of The Dead. University of Hawaii Press. p. 17.

- ^ Hong, Jeehee (2016). Theater Of The Dead. University of Hawaii Press. p. 19.

- ^ Nower, Tahseen (30 August 2023). "Rudaalis: The tear sellers of Rajasthan". The Financial Express. Retrieved 3 October 2024.

- ^ Douglas, Lawrence (2017). Law and Mourning. University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 59–93. ISBN 978-1-61376-530-2.

- ^ Davey, Richard (1889). A History of Mourning. pp. 26–51. ISBN 9333101268.

- ^ a b "Amos 5 Commentary - John Gill's Exposition on the Whole Bible". StudyLight.org. Archived from the original on 2018-04-30. Retrieved 2018-04-29.

- ^ Yiwu, Liao Yiwu (2009). The Corpse Walker. Anchor. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-307-38837-7.

- ^ a b Lim, Louisa Lim (2013-06-23). "Belly Dancing For The Dead: A Day With China's Top Mourner". WNYC.

- ^ a b c "Performing at funerals: professional mourners in Chongqing and Chengdu". Danwei.org. July 23, 2010. Archived from the original on 2010-07-26.

- ^ "Rent A Mourner". www.rentamourner.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2013-03-28. Retrieved 2020-12-14.

- ^ a b c "I'm Paid To Mourn At Funerals (And It's A Growing Industry)". Cracked.com. 21 March 2016. Archived from the original on 2018-04-27. Retrieved 2018-04-27.

- ^ a b c Abbott, Lyman; Conant, Thomas Jefferson (1885). A Dictionary of Religious Knowledge, for Popular and Professional Use: Comprising Full Information on Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Subjects. With Several Hundred Maps and Illustrations. Harper & brothers.

- ^ "Funeral In Berlin". IMDB. Archived from the original on 2020-09-05. Retrieved 2020-07-16.

- ^ "Rudaali". University of Iowa. Archived from the original on 2013-10-19. Retrieved 2014-09-01.

- ^ "Tabaki". IMDB. Archived from the original on 2016-09-26. Retrieved 2015-05-29.

- ^ "Crying Ladies". IMDB. Archived from the original on 2017-02-09. Retrieved 2017-09-16.

- ^ "Miewoharu". IMDB. Archived from the original on 2017-02-13. Retrieved 2017-09-21.

- ^ Balzac, Honoré de. Father Goriot. (The Works of Honoré de Balzac. Vol. XIII.) Philadelphia: Avil Publishing Company, 1901.

- ^ Forster, E. M. Howards End. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1910.

- ^ Zakes., Mda (2002). Ways of dying : a novel (1st Picador USA ed.). New York: Picador USA. ISBN 978-0-312-42091-8. OCLC 49550849.

- Footnote 1 in Sabar, Y. (1976). "Lel-Huza: Story and History in a Cycle of Lamentations for the Ninth of Ab in the Jewish Neo-Aramaic Dialect of Zakho, Iraqi Kurdistan." Journal of Semitic Studies (21) 138–162.