Pierre-François-Léonard Fontaine

Pierre-François-Léonard Fontaine | |

|---|---|

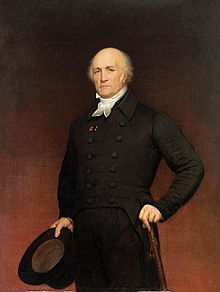

Pierre-François-Léonard Fontaine by Joseph-Désiré Court | |

| Born | 20 September 1762 Pontoise, France |

| Died | 10 October 1853 (aged 91) Paris, France |

| Burial place | Père Lachaise |

| Other names | Pierre Fontaine |

| Education | Instruction by Antoine-François Peyre |

| Occupation(s) | Architect, designer, interior decorator, artist |

| Known for | Creation of the Directoire style and the Empire style |

| Notable work | Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel, Galerie d'Orléans, Chapelle expiatoire, western portion of the Rue de Rivoli |

| Honours | Legion of honor, Prix de Rome |

Pierre-François-Léonard Fontaine (pronounced [pjɛʁ frɑ̃swa leɔnaːʁ fɔ̃tɛn]; 20 September 1762 – 10 October 1853) was a French neoclassical architect, interior decorator, designer and artist.

In addition to his important contributions to the architecture and interior design of his day, Pierre Fontaine was remarkable for his ability to not only prosper in his architectural career, but also to survive the numerous tumultuous regime changes – his architectural practice prospered for seven decades, from the Consulate to the reign of Napoleon III, almost without interruption.

Life and work

Fontaine was born in Pontoise, Val-d'Oise in 1762. His father, Pierre Fontaine (1735-1807), was an architect and fountain designer.[1] In 1778 and 1779, the 16-year old participated, with his father, on building the hydraulic systems at the Château de L'Isle-Adam,[2] which belonged to Louis-François-Joseph de Bourbon, Count of La Marche and Prince of Conti.[3]

Education and the beginning of the partnership with Percier

In 1779, he moved to Paris, where he followed the teachings of Antoine-François Peyre.[1] He was elected to the Académie de Beaux-arts in 1782 and won the second Prix de Rome in 1785 (he lived in Rome for several years starting in 1787).[1] It was during this period that he met Charles Percier, a fellow student in Peyre’s workshop (Percier also won the prix de Rome and joined Fontaine there a year later).[2][4]

The encounter between the two men was the beginning of a lifetime partnership. Starting in 1794, Fontaine worked so closely with Percier that it is difficult to distinguish their work.[1][5] A 19th century observer noted the following about their intertwined careers: "It is surprising what a complete mastery these young men in a few years contrived to exercise over the tastes of their day."[5]

Early career

Fontaine and Percier were jointly named directors of stage decoration at the Paris Opera from 1794 to 1796.[1][3] In 1798, they published their successful collection of line drawings made during their stay in Rome, Palais, maisons et autres édifices dessinés à Rome.[6] Their initial successes in interior decoration came while serving wealthy, private clients: "The first clients of Percier and Fontaine were the financiers Ouvrard, Chauvelin and Gaudin, who had their recently acquired hotels in the Chaussée d'Antin district fitted out and decorated."[7]

These early, private projects attracted the interest of Joséphine de Beauharnais and of Napoleon. In 1799, the artist, Jacques-Louis David,[8] introduced Fontaine to Joséphine de Beauharnais, Napoleon’s first wife. Fontaine is soon named architect of the Invalides in 1800 and architect of the government in 1801.[3] This link to the Emperor Napoleon was to be the source of numerous architectural and decorating projects until Napoleon abdicated and was banished to the island of Elba in 1814. Indeed, one analysis of Napoleon's impact on the architecture and urban design of Paris states that Percier and Fontaine were the two "most important architects of his reign".[9]:31

As demand for their services grew, Fontaine and Percier became influential proponents of French neoclassicism, which they perfected and promoted through their numerous projects, their publications and through Percier’s teachings at the Ecole de Beaux Arts.[10] Relatedly, they are credited with being among the principal creators of the Directoire style and the Empire style. They deployed their Empire style in numerous interior decors and in restoration work on the royal residences of Malmaison, Saint-Cloud, Compiègne and Fontainebleau.[10]

Fontaine and Percier also applied this style in the design of furniture, tapestries and porcelain as well as in their architecture and interior design projects. The style proved to be influential in courts across Europe.[11][8]

One of their major collaborations was the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel, which was modelled on the Arch of Constantine (312 AD) in Rome and which celebrates Napoleon's military victories. It is located at the eastern end of the line following the Champs-Élysées, starting at the Arc de Triomphe de l'Étoile and passing through the Tuileries garden. Fontaine and Percier also pierced the first, western part of the rue de Rivoli, including its distinctive arcades, and built the northern, 'Rivoli' wing of the Louvre, thereby competing the Cour Carrée.[9]:199 Fontaine also served as an advisor on the Arc de Triomphe de l'Étoile.[3] Fontaine was also the architect of the Galerie d'Orléans, rebuilt in 1830 on the site of the former Galeries de Bois, as part of the Palais Royal in Paris.[12] Most of this Galerie was demolished in the 1930s and the only vestiges are a series of columns on the southern end of the garden.

In the area of architecture, much of their work during the Napoleonic period involved restoration or extensions of existing buildings. While they proposed and designed new buildings for Napoleon, especially the Palais du Roi de Rome (Palace of the King of Rome, to be built for Napoleon’s son on the site of what is now the Trocadero in Paris), many of these projects were never built or completed.[8] This reflected the ups and downs of Napoleon's career,[9]:219 his financial constraints[9]:81 and the fact that Napoleon, as a client of construction projects (and unlike his battlefield persona) was prudent, hesitant and indecisive.[9]:10

Partnership with Percier

Percier and Fontaine lived together as well as being colleagues and partners. Their different personalities and interests meant that they played different roles within the partnership. Fontaine assumed the public role and was the active manager of their projects and relations with clients, while Percier led a more reclusive existence in his apartments in the Louvre, while still participating conceptually in their joint projects.[6][9]:33

Fontaine married late in life and adopted the daughter of his wife.[6] Following Charles Percier's death in 1838, Fontaine designed a tomb for him in their characteristic style in the Pere Lachaise Cemetery.

Death

Fontaine died in Paris on 10 October 1853 at the age of 91 years.[3] His body was interred in the tomb he designed for Percier, in accordance with his wishes. His successful career spanned seven turbulent decades marked by the French Revolution, the Directory, the Napoleonic Empire, the Restoration, the July Monarchy and the governments of Napoleon III.[3]

Timeline

A timeline of the main events and projects in Fontaine's life and career is as follows:

- 1779. Fontaine moves to Paris to study architecture and meets Percier.[3]

- 1787-1790. He resides at the Academy of France in Rome.[3]

- 1792. Fontaine stays several months in England.[3]

- 1798-1799. Restoration of several private mansions in Paris.

- 1800-1802. Restoration and decoration of the Château de Malmaison for Joséphine de Beauharnais. Restoration of the Palais des Tuileries and of the Château de Saint-Cloud.

- 1802. Fontaine and Percier draw up the plans for the rue de Rivoli.[10]

- 1804-1812. Work on the Louvre and Tuileries complex, including refurbishment of the Grande galerie du Louvre (1804-1812); first projects linking the two royal residences that made up the Louvre at the time in order to create a single royal residence (1806); western portion of the rue de Rivoli; construction of the arc de triomphe du Carrousel (1806-1808). Fontaine and Percier are also deeply involved in the development of designs for the imperial tapestry manufacturers at Gobelins and at the Savonnerie as well as being chief architects for the marble warehouses and all the imperial buildings within the walls of Paris.[3]

- 1810. Fontaine and Percier win the Grand Prix of Architecture for their arc de triomphe du Carrousel.[3]

- 1811. Fontaine is elected to the Academy of Beaux-arts and receives the Legion of Honour.[3]

- 1812. Publication by Fontaine and Percier of their Recueil de décorations intérieures, the handbook of Empire style.[11]

- 1813. He is named first architect of the Emperor Napoleon.[9] When this post is suppressed in 1814, he becomes architect of Paris, of the King (Louis XVIII) and of the Duke of Orleans.[3]

- 1816. He begins work on the Chapelle expiatoire consecrated to the memory of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette. The chapel is located on the spot where the royal couple was buried in a mass grave located in what is now the 8th arrondissement of Paris. Construction was completed in 1826. Percier did not work on this project because he disapproved of it.

- 1829-1831. Fontaine and Percier create a galerie d'Orléans, a covered passage in the Palais Royal.

- 1838. Death of Charles Percier on September 5.

- 1843. The church, Notre-Dame-de-la-Compassion is built using Fontaine's plans on the site of the accidental death of Ferdinand-Philippe d'Orleans.[3]

- 1848. Fontaine is maintained, at 86 years of age, in his position as the architect of government buildings in Paris. He resigns from most of his responsibilities later in the same year.[3]

- 1853. Death on October 10.[3]

See also

References

- Parts of this page are translated from the corresponding French Wikipedia page, Fr:Pierre Fontaine (architecte).

- ^ a b c d e "Pierre Fontaine architecte". paris1900.lartnouveau.com. Retrieved 2024-08-02.

- ^ a b "Pierre Fontaine, un architecte novateur". Pontoise | Ville d'art et d'histoire (in French). Retrieved 2024-08-02.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Fonds Pierre Fontaine (1764-1865, 1917)". FranceArchives. Retrieved 2024-08-02.

- ^ Raoul-Rochette (1840). "Percier. Sa vie et ses ouvrages". Période initiale: 246–268.

- ^ a b "The Style of "The Empire"". The Art Amateur. 5 (1): 11. 1881. ISSN 2151-8246. JSTOR 25627430.

- ^ a b c Van Zanten, David (1988). "Fontaine in the Burnham Library". Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies. 13 (2): 133–145. doi:10.2307/4115897. ISSN 0069-3235. JSTOR 4115897.

- ^ Lafont, Anne (2005). "À La Recherche D'une Iconographie « Incroyable » Et « Merveilleuse »: Les Panneaux Décoratifs Sous Le Directoire". Annales historiques de la Révolution française (340): 5–21. ISSN 0003-4436. JSTOR 41889181.

- ^ a b c Huyghe, Rene (1968). "Napoléon Et Les Arts". Revue des Deux Mondes (1829-1971): 13–31. ISSN 0035-1962. JSTOR 44599435.

- ^ a b c d e f g Poisson, Georges (2002). Napoleon 1er et Paris (in French). Paris: Tallandier. pp. 33, 236. ISBN 2-84734-011-4.

- ^ a b c "Les architectes : Percier et Fontaine". Passerelles (in French). Retrieved 2024-08-02.

- ^ a b Gontar, Cybele. "Empire Style, 1800–1815 | Essay | The Metropolitan Museum of Art | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History". The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Retrieved 2024-08-02.

- ^ "Palais Royal. Galerie d'Orléans". Art, Architecture and Engineering Library.

Further reading

- Charles Percier, Pierre François Léonard Fontaine (2018): The Complete Works of Percier and Fontaine. New York, Princeton Architectural Press, 2018, ISBN 9781616896980.

External links

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Percier and Fontaine, Linda Rapp, glbtq

- Percier and Fontaine Collection