Permutation (music)

In music, a permutation (order) of a set is any ordering of the elements of that set.[3] A specific arrangement of a set of discrete entities, or parameters, such as pitch, dynamics, or timbre. Different permutations may be related by transformation, through the application of zero or more operations, such as transposition, inversion, retrogradation, circular permutation (also called rotation), or multiplicative operations (such as the cycle of fourths and cycle of fifths transforms). These may produce reorderings of the members of the set, or may simply map the set onto itself.

Order is particularly important in the theories of composition techniques originating in the 20th century such as the twelve-tone technique and serialism. Analytical techniques such as set theory take care to distinguish between ordered and unordered collections. In traditional theory concepts like voicing and form include ordering; for example, many musical forms, such as rondo, are defined by the order of their sections.

The permutations resulting from applying the inversion or retrograde operations are categorized as the prime form's inversions and retrogrades, respectively. Applying both inversion and retrograde to a prime form produces its retrograde-inversions, considered a distinct type of permutation.

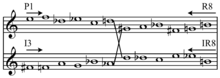

Permutation may be applied to smaller sets as well. However, transformation operations of such smaller sets do not necessarily result in permutation the original set. Here is an example of non-permutation of trichords, using retrogradation, inversion, and retrograde-inversion, combined in each case with transposition, as found within the tone row (or twelve-tone series) from Anton Webern's Concerto:[4]

If the first three notes are regarded as the "original" cell, then the next 3 are its transposed retrograde-inversion (backwards and upside down), the next three are the transposed retrograde (backwards), and the last 3 are its transposed inversion (upside down).[5]

Not all prime series have the same number of variations because the transposed and inverse transformations of a tone row may be identical, a quite rare phenomenon: less than 0.06% of all series admit 24 forms instead of 48.[6]

One technique facilitating twelve-tone permutation is the use of number values corresponding with musical letters. The first note of the first of the primes, actually prime zero (commonly mistaken for prime one), is represented by 0. The rest of the numbers are counted half-step-wise such that: B = 0, C = 1, C♯/D♭ = 2, D = 3, D♯/E♭ = 4, E = 5, F = 6, F♯/G♭ = 7, G = 8, G♯/A♭ = 9, A = 10, and A♯/B♭ = 11.

Prime zero is retrieved entirely by choice of the composer. To receive the retrograde of any given prime, the numbers are simply rewritten backwards. To receive the inversion of any prime, each number value is subtracted from 12 and the resulting number placed in the corresponding matrix cell (see twelve-tone technique). The retrograde inversion is the values of the inversion numbers read backwards.

Therefore:

A given prime zero (derived from the notes of Anton Webern's Concerto):

0, 11, 3, 4, 8, 7, 9, 5, 6, 1, 2, 10

The retrograde:

10, 2, 1, 6, 5, 9, 7, 8, 4, 3, 11, 0

The inversion:

0, 1, 9, 8, 4, 5, 3, 7, 6, 11, 10, 2

The retrograde inversion:

2, 10, 11, 6, 7, 3, 5, 4, 8, 9, 1, 0

More generally, a musical permutation is any reordering of the prime form of an ordered set of pitch classes [7] or, with respect to twelve-tone rows, any ordering at all of the set consisting of the integers modulo 12.[8] In that regard, a musical permutation is a combinatorial permutation from mathematics as it applies to music. Permutations are in no way limited to the twelve-tone serial and atonal musics, but are just as well utilized in tonal melodies especially during the 20th and 21st centuries, notably in Rachmaninoff's Variations on the Theme of Paganini for orchestra and piano.[citation needed]

Cyclical permutation (also called rotation)[9] is the maintenance of the original order of the tone row with the only change being the initial pitch class, with the original order following after. A secondary set may be considered a cyclical permutation beginning on the sixth member of a hexachordally combinatorial row. The tone row from Berg's Lyric Suite, for example, is realized thematically and then cyclically permuted (0 is bolded for reference):

5 4 0 9 7 2 8 1 3 6 t e 3 6 t e 5 4 0 9 7 2 8 1

See also

References

- ^ Nolan, Catherine. 1995. "Structural Levels and Twelve-Tone Music: A Revisionist Analysis of the Second Movement of Webern's 'Piano Variations Op. 27'", p.49–50. Journal of Music Theory, Vol. 39, No. 1 (Spring), pp. 47–76. For whome 0 = G♯.

- ^ Leeuw, Ton de. 2005. Music of the Twentieth Century: A Study of Its Elements and Structure, p.158. Translated from the Dutch by Stephen Taylor. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 90-5356-765-8. Translation of Muziek van de twintigste eeuw: een onderzoek naar haar elementen en structuur. Utrecht: Oosthoek, 1964. Third impression, Utrecht: Bohn, Scheltema & Holkema, 1977. ISBN 90-313-0244-9. For whom 0 = E♭.

- ^ Allen Forte, The Structure of Atonal Music (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1973): 3; John Rahn, Basic Atonal Theory (New York: Longman, 1980), 138

- ^ Whittall, Arnold. 2008. The Cambridge Introduction to Serialism. Cambridge Introductions to Music, p.97. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68200-8 (pbk).

- ^ George Perle, Serial Composition and Atonality: An Introduction to the Music of Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern, fourth edition, revised (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 1977): 79. ISBN 0-520-03395-7.

- ^ Emmanuel Amiot, "La série dodécaphonique et ses symétries", Quadrature 19, EDP sciences[clarification needed] (1994).

- ^ Wittlich, Gary (1975). "Sets and Ordering Procedures in Twentieth-Century Music", Aspects of Twentieth-Century Music. Wittlich, Gary (ed.). Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-049346-5 p. 475.

- ^ John Rahn, Basic Atonal Theory (New York: Longman, 1980), 137.

- ^ John Rahn, Basic Atonal Theory (New York: Longman, 1980), 134