Omaha people

Umoⁿhoⁿ | |

|---|---|

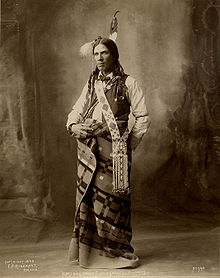

Omaha tribal dancer | |

| Total population | |

| 6,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| English, Omaha-Ponca | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, Native American religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Siouan and Dhegihan peoples, esp. Ponca, Otoe, Osage, Iowa |

| People | Umoⁿhoⁿ |

|---|---|

| Language | Umoⁿhoⁿ Iyé, Umoⁿhoⁿ Gáxe |

| Country | Umoⁿhoⁿ Mazhóⁿ |

The Omaha Tribe of Nebraska (Omaha-Ponca: Umoⁿhoⁿ)[1] are a federally recognized Midwestern Native American tribe who reside on the Omaha Reservation in northeastern Nebraska and western Iowa, United States. There were 5,427 enrolled members as of 2012.[2] The Omaha Reservation lies primarily in the southern part of Thurston County and northeastern Cuming County, Nebraska, but small parts extend into the northeast corner of Burt County and across the Missouri River into Monona County, Iowa. Its total land area is 307.03 sq mi (795.2 km2)[3] and the reservation population, including non-Native residents, was 4,526 in the 2020 census.[4] Its largest community is Pender.[citation needed]

The Omaha people migrated to the upper Missouri area and the Plains by the late 17th century from earlier locations in the Ohio River Valley. The Omaha speak a Siouan language of the Dhegihan branch, which is very similar to that spoken by the Ponca. The latter were part of the Omaha before splitting off into a separate tribe in the mid-18th century. They were also related to the Siouan-speaking Osage, Quapaw, and Kansa peoples, who also migrated west under pressure from the Iroquois in the Ohio Valley. After pushing out other tribes, the Iroquois kept control of the area as a hunting ground.

About 1770, the Omaha became the first tribe on the Northern Plains to adopt equestrian culture.[5] Developing "The Big Village" (Ton-wa-tonga) about 1775 in current-day Dakota County in northeast Nebraska, the Omaha developed an extensive trading network with early European explorers and French Canadian voyageurs. They controlled the fur trade and access to other tribes on the Upper Missouri River.

Omaha, Nebraska, the largest city in Nebraska, is named after them. Never known to take up arms against the U.S., the Omaha assisted the U.S. during the American Civil War.

History

The Omaha tribe began as a larger Eastern Woodlands tribe comprising both the Omaha, Ponca and Quapaw tribes. This tribe coalesced and inhabited the area near the Ohio and Wabash rivers around year 1600.[6] As the tribe migrated west, it split into what became the Omaha and the Quapaw tribes. The Quapaw settled in what is now Arkansas and the Omaha, known as U-Mo'n-Ho'n ("upstream")[7] settled near the Missouri River in what is now northwestern Iowa. Another division happened, with the Ponca becoming an independent tribe, but they tended to settle near the Omaha. The first European journal reference to the Omaha tribe was made by Pierre-Charles Le Sueur in 1700. Informed by reports, he described an Omaha village with 400 dwellings and a population of about 4,000 people. It was located on the Big Sioux River near its confluence with the Missouri, near present-day Sioux City, Iowa. The French then called it "The River of the Mahas."

In 1718, the French cartographer Guillaume Delisle mapped the tribe as "The Maha, a wandering nation", along the northern stretch of the Missouri River. French fur trappers found the Omaha on the eastern side of the Missouri River in the mid-18th century. The Omaha were believed to have ranged from the Cheyenne River in South Dakota to the Platte River in Nebraska. Around 1734 the Omaha established their first village west of the Missouri River on Bow Creek in present-day Cedar County, Nebraska.

Around 1775, the Omaha developed a new village, probably located near present-day Homer, Nebraska.[5] Ton won tonga (or Tonwantonga, also called the "Big Village"), was the village of Chief Blackbird. At this time, the Omaha controlled the fur trade on the Missouri River. About 1795, the village had around 1,100 people.[8]

Around 1800, a smallpox epidemic, resulting from contact with Europeans, swept the area, reducing the tribe's population dramatically by killing approximately one-third of its members.[5] Chief Blackbird was among those who died that year. Blackbird had established trade with the Spanish and French, and used trade as a security measure to protect his people. Aware they traditionally lacked a large population as defense from neighboring tribes, Blackbird believed that fostering good relations with white explorers and trading were the keys to their survival. The Spanish built a fort nearby and traded regularly with the Omaha during this period.[8]

After the United States made the Louisiana Purchase and exerted pressure on the trading in this area, there was a proliferation of different kinds of goods among the Omaha: tools and clothing became prevalent, such as scissors, axes, top hats and buttons. Women took on more manufacturing of goods for trade, as well as hand farming, perhaps because of evolving technology. Those women buried after 1800 had shorter, more strenuous lives; none lived past the age of 30. But they also had larger roles in the tribe's economy. Researchers have found through archeological excavations that the later women's skeletons were buried with more silver artifacts as grave goods than those of the men, or of women before 1800.[5] After the research was completed, the tribe buried these ancestral remains in 1991.

When Lewis and Clark visited Ton-wa-tonga in 1804, most of the inhabitants were gone on a seasonal buffalo hunt. The expedition met with the Oto people, who were also Siouan speaking. The explorers were led to the gravesite of Chief Blackbird before continuing on their expedition west. In 1815 the Omaha made their first treaty with the United States, one called a "treaty of friendship and peace." No land was relinquished by the tribe.[8]

Semi-permanent Omaha villages lasted from 8 to 15 years. They created sod houses for winter dwellings, which were arranged in a large circle in the order of the five clans or gentes of each moitie, to keep the balance between the Sky and Earth parts of the tribe. Eventually, disease and Sioux aggression from the north forced the tribe to move south. Between 1819 and 1856, they established villages near what is now Bellevue, Nebraska and along Papillion Creek.

Loss of lands

By the Fourth Treaty of Prairie du Chien in 1831, the Omaha ceded their lands in Iowa to the United States, east of the Missouri River, with the understanding that they still had hunting rights there. In 1836 a treaty with the US took their remaining hunting lands in northwestern Missouri.[8]

During the 1840s, the Omaha continued to suffer from Sioux aggression. European-American settlers pressed the US government to make more land available west of the Mississippi River for white development. In 1846 Big Elk made an illegal treaty allowing a large group of Mormons to settle on Omaha land for a period; he hoped to gain some protection from competing natives by their guns, but the new settlers cut deeply into the game and wood resources of the area during the two years they were there.[9]

For nearly 15 years in the 19th century, Logan Fontenelle was the interpreter at the Bellevue Agency, serving different US Indian agents. The mixed-race Omaha-French man was trilingual and also worked as a trader. His mother was Omaha; his father French Canadian. In January 1854 he acted as interpreter during the agent James M. Gatewood's negotiations for land cessions with 60 Omaha leaders and elders, who sat in council at Bellevue. Gatewood had been under pressure by Washington headquarters to achieve a land sale. The Omaha elders refused to delegate the negotiations to their gens chiefs, but came to an agreement to sell most of their remaining lands west of the Missouri to the United States. Competing interests may be shown by the draft treaty containing provisions for payment of tribal debts to the traders Fontenelle, Peter Sarpy, and Louis Saunsouci.[10] The chiefs at council agreed to move from the Bellevue Agency further north, finally choosing the Blackbird Hills, essentially the current reservation in Thurston County, Nebraska.

The 60 men designated seven chiefs to go to Washington, DC for final negotiations along with Gatewood, with Fontenelle to serve as their interpreter.[10][11] The chief Iron Eye (Joseph LaFlesche) was among the seven who went to Washington and is considered the last chief of the Omaha under their traditional system. Logan Fontenelle served as their interpreter, and whites mistakenly believed he was a chief. Because his father was white, the Omaha never accepted him as a member of the tribe, but considered him white.[11]

Although the draft treaty authorized the seven chiefs to make only "slight alterations," the government officials forced major changes when they met.[10] It took out the payments to the traders. It reduced the total value of annuities from $1,200,000 to $84,000, spread over years until 1895. It reserved the right to decide on distribution between cash and goods for the annuities.[10]

The tribe finally removed to the Blackbird Hills about 1856, and they first built a village in its traditional pattern. By the 1870s, bison were quickly disappearing from the plains, and the Omaha had to rely increasingly for survival upon their cash annuities and supplies from the United States Government and adaptation to subsistence agriculture. Jacob Vore was a Quaker appointed as US Indian agent to the Omaha Reservation under President Ulysses S. Grant. He started in September 1876, succeeding T.S. Gillingham, also a Quaker.

Vore distributed a reduced annuity that year, just before the Omaha left on their annual buffalo hunt; according to his later account, he intended to "encourage" the Omaha to work at more agriculture.[13] They suffered a poor hunting season and severe winter, so that some were starving before late spring. Vore gained a supplement to the annuities which he had distributed, but for the remaining years of his tenure through 1879, distributed no cash annuities of the $20,000/year which was part of the treaty. Instead, he supplied goods: harrows, wagons, harnesses and various kinds of plows and implements to support the agricultural work. He told the tribe that Washington, DC officials had disapproved the annuity. The people had no recourse, and struggled to raise more produce, increasing the harvest to 20,000 bushels.[13]

The Omaha never took up arms against the U.S. Several members of the tribe fought for the Union during the American Civil War, as well as each subsequent war through today.

Beginning in the 1960s, the Omaha began to reclaim lands east of the Missouri River, in an area called Blackbird Bend. After lengthy court battles and several standoffs, much of the area has been recognized as part Omaha tribal lands.[14] The Omaha established their Blackbird Bend Casino on this reclaimed territory.[15]

Archaeology

In 1989, the Omaha reclaimed more than 100 ancestral skeletons from Ton-wo-tonga, which had been held by museums. They had been excavated during archaeological work of the 1930s and 1940s, from grave sites with burials before and after 1800. Before having ceremonial reburial of the remains on Omaha lands, the tribe's representatives arranged for research at the University of Nebraska to see what could be learned from their ancestors.[5]

Researchers found considerable differences in the community before and after 1800, as revealed in their bones and artifacts. Most significantly, they discovered that the Omaha were an equestrian Plains culture and buffalo hunters by 1770, making them the "first documented equestrian culture on the Northern Plains."[5] They also found that before 1800, the Omaha traded mostly in arms and ornaments. Men had many more roles in the patrilineal culture than did women: as "archers, warriors, gunsmiths, and merchants," including the major ceremonial roles. Sacred bundles from religious ceremonies were found buried only with men.[5]

Culture

In pre-settlement times, the Omaha had an intricately developed social structure that was closely tied to the people's concept of an inseparable union between sky (male principle) and earth (female); it was part of their creation story and their view of the cosmos. This union was viewed as critical to perpetuation of all living forms and pervaded Omaha culture. The tribe was divided into two moieties or half-tribes, the Sky People (Insta'shunda) and the Earth People (Hon'gashenu),[16] each led by a different hereditary chief, who inherited power from his father's line.[17]

Sky people were responsible for the tribe's spiritual needs and Earth people for the tribe's physical welfare. Each moiety was composed of five clans or gente, which also had differing responsibilities. Each gens had a hereditary chief, through the male lines, as the tribe had a patrilineal kinship system of descent and inheritance. Children were considered to be born to their father's clan. Individuals married persons from another gens, not within their own.[11][17]

The hereditary chiefs and clan structures still existed at the time the elders and chiefs negotiated with the United States to cede most of their land in Nebraska in exchange for protection and cash annuities. Only men born into hereditary lines through their fathers, or formally adopted by a male into the tribe, as Joseph LaFlesche (Iron Eye) was by the chief Big Elk in the 1840s, could become chiefs. Big Elk designated LaFlesche as his son and successor chief of the Weszinste.[11] LaFlesche, a man of mixed race, was the last recognized head chief selected by the traditional ways, and he was the only chief with any European ancestry.[18] He served for decades from 1853.

Although whites considered Logan Fontenelle a chief, the Omaha did not. They used him as an interpreter; he was of mixed-race with a white father, so was considered white, as he had not been adopted by a man of the tribe.[11]

Today the Omaha host an annual pow wow. At the celebration, a committee elects the Omaha Pow Wow Princess. She serves as a representative in the community and a role model for younger children.[19]

In the rite of passage of the Omaha boys enter the wilderness alone they fast and pray and should they dream of a woman's burden- strap (a tool used to help carry things), they feel compelled to dress and live in every way live as women. Such men are known as mixugo.[20]

Dwellings

As the tribe migrated westward from the Ohio River region in the 17th century, they adapted to the Plains environment. They replaced the Woodland custom of bark lodges with tipis (borrowed from the Sioux) for the buffalo hunting and summer season, and built earth lodges (borrowed from the Arikara,[21] called Sand Pawnee,[22]) for the winter. Tipis were used primarily during buffalo hunts and when they relocated from one village area to another. They used earth lodges as dwellings during the winter.

Omaha beliefs were symbolized in their dwelling structures. During most of the year, the Omaha lived in earth or sod lodges, ingenious structures with a timber frame and a thick sod covering. At the center of the lodge was a fireplace that recalled their creation myth. The earthlodge entrance was built to face east, to catch the rising sun and remind the people of their origin and migration upriver from the east.

The Huthuga, the circular layout of tribal villages, reflected the tribe's beliefs. Sky people lived in the northern half-circle of the village, the area that symbolized the heavens. Earth people lived in the southern half, which represented the earth. The circle opened to the east. Within each half of the village, the clans or gentes were located based on their members' tribal duties and relationship to other clans. Earth lodges were as large as 60 feet (18 m) in diameter and might hold several families, even their horses.

When the tribe removed to the Omaha Reservation about 1856, they initially built their village and earth lodges in the traditional patterns, with the half-tribes and clans in their traditional places in the layout.

Religion

The Omaha revere an ancient Sacred Pole, from before the time of their migration to the Missouri, made of cottonwood. It is called Umoⁿ'hoⁿ'ti (meaning "The Real Omaha") and considered to be a person.[17] It was kept in a Sacred Tent in the center of the village, which only men who were members of the Holy Society could enter. An annual renewal ceremony was related to the Sacred Pole.[16]

In 1888 Francis La Flesche, a young Omaha anthropologist, helped arrange for his colleague Alice Fletcher to have the Sacred Pole taken to the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University, for preservation of it and its stories, at a time when the tribe's continuity seemed threatened by pressure for assimilation. The tribe was considering burying the Pole with its last keeper after his death. The last renewal ceremony for the pole was held in 1875, and the last buffalo hunt in 1876.[17] La Flesche and Fletcher gathered and preserved stories about the Sacred Pole by its last keeper, Yellow Smoke, a holy man of the Hong'a gens.[16]

In the twentieth century, about 100 years after the Pole had been transferred, the tribe negotiated with the Peabody Museum for its return. The tribe planned to install the Sacred Pole in a cultural center to be built. When the museum returned the Sacred Pole to the tribe in July 1989, the Omaha held an August pow-wow in celebration and as part of their revival.[16]

The Sacred Pole is said to represent the body of a man. The name by which it is known, a-kon-da-bpa, is the word used to designate the leather bracer worn upon the wrist for protection from the bow string (of the weapon of bow and arrow). This name demonstrates that the pole was intended to symbolize a man, as no other creature could wear a bracer. It also indicated that the man thus symbolized was one who was both a provider for and a protector of his people.[17]

Films

- 1990 – The Return of the Sacred Pole. Produced and directed by Michael Farrell. Produced by KUON-TV with support from Native American Public Telecommunications

- 2018 – The Omaha Speaking. Directed by Brigitte Timmerman. Narrated by Tatanka Means. A Range Films Production.[23][24]

Communities

Notable Omaha people

- Blackbird, chief

- Big Elk (1770–1846/1853), chief, adopted Joseph LaFlesche and groomed him as chief

- Francis M. Cayou, football coach

- Logan Fontenelle (1825–1855), interpreter

- Rodney A. Grant (b. 1959), actor

- Joseph LaFlesche (Iron Eye, ca. 1820–1888), adopted and named by chief, only chief known to have European ancestry; last traditional chief of the Omaha

- Francis La Flesche (1857–1932), first Native American ethnologist

- Susan La Flesche Picotte (1865–1915), first Native American physician

- Susette LaFlesche Tibbles (1854–1903), author and indigenous rights activist

- Jeremiah Bitsui, actor

- Thomas L. Sloan (1863–1940), first Native American lawyer to argue before U.S. Supreme Court

- Hiram Chase (1861–1928), with Thomas L. Sloan, formed first Native American law firm in the U.S.

- Nathan Phillips (b. 1954), Native American activist

References

- ^ "Omaha Ponca Dictionary Index". omahaponca.unl.edu. Retrieved 2018-10-10.

- ^ "Winnebago Agency". www.bia.gov. Bureau of Indian Affairs.

- ^ "2020 Gazetteer Files". census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ "2020 Decennial Census: Omaha Reservation, NE--IA". data.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g Paulette W. Campbell, "Ancestral Bones: Reinterpreting the Past of the Omaha" Archived 2018-01-11 at the Wayback Machine, Humanities, November/December 2002, Volume 23/Number 6, accessed 26 August 2011

- ^ Mathews (1961), The Osages

- ^ John Joseph Mathews, The Osages: Children of the Middle Waters (University of Oklahoma Press 1961), pages 110, 128, 140, 282

- ^ a b c d (2007) "History at a glance" Archived 2008-10-29 at the Wayback Machine, Douglas County Historical Society. Retrieved 2/2/08.

- ^ Boughter, Betraying the Omaha, pp. 49–50

- ^ a b c d Judith A. Boughter, Betraying the Omaha Nation, 1790–1916, University of Oklahoma Press, 1998, pp. 61–62

- ^ a b c d e Melvin Randolph Gilmore, "The True Logan Fontenelle", Publications of the Nebraska State Historical Society, Vol. 19, edited by Albert Watkins, Nebraska State Historical Society, 1919, p. 64, at GenNet, accessed 25 August 2011

- ^ Gilmore, Melvin R.: "Methods of Indian Buffalo Hunts, with the Itinerary of the Last Tribal Hunt of the Omaha". Papers of the Michigan Academy of Science, Arts and Letters. Vol.XVI, (1931), pp. 17–32.

- ^ a b Jacob Vore, "The Omaha of Forty Years Ago", in Publications of the Nebraska State Historical Society, Vol. 19, edited by Albert Watkins, Nebraska State Historical Society, 1919, pp. 115–117, accessed 25 August 2011

- ^ Scherer, Mark R. (1998) "Imperfect Victory: The Legal Struggle for Blackbird Bend, 1966–1995", Annals of Iowa 57:38–71.

- ^ About Blackbird Bend, "Blackbird Bend Casino – About Blackbird Bend Casino". Archived from the original on 2014-05-21. Retrieved 2014-05-21.

- ^ a b c d Robin Ridington, "A Sacred Object as Text: Reclaiming the Sacred Pole of the Omaha Tribe", American Indian Quarterly 17(1): 83 – 99, 1993, reprinted at Umoⁿ'hoⁿ Heritage, Omaha Tribe Website

- ^ a b c d e Alice C. Fletcher, and Francis La Flesche, The Omaha Tribe, Washington, D.C.: Twenty-Seventh Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, Smithsonian Institution, 1911

- ^ "Joseph La Flesche: Sketch of the Life of the Head Chief of the Omaha", first published in the (Bancroft, Nebraska) Journal; reprinted in The Friend, 1889, accessed 23 August 2011

- ^ "Pow-Wow Princess Song". World Digital Library. 1983-08-13. Retrieved 2013-08-03.

- ^ Turner, Victor (1964). "Betwixt and Between: The Liminal period in Rites de passage". Proceedings of the American Ethnological Society 1964. West Publishing Company.

- ^ Fletcher, Alice C. and Francis La Flesche: The Omaha Tribe. Lincoln and London, 1992. P. 112.

- ^ Fletcher, Alice C. and Francis La Flesche: The Omaha Tribe. Lincoln and London, 1992. P. 102.

- ^ "The Omaha Speaking". The Omaha Speaking. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ Peters, Chris (5 July 2018). "The Omaha Tribe's language is fading. A new documentary hopes to help preserve it". Omaha World-Herald. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

Further reading

- R.F. Fortune: Omaha Secret Societies, Reprint from New York: Columbia University Press, 1932; New York: AMS Press, Inc., 1969

- Francis LaFlesche, The Middle Five: Indian Schoolboys of the Omaha Tribe. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1900/1963.

- Karl J. Reinhard, Learning from the Ancestors: The Omaha Tribe Before and After Lewis and Clark. University of Nebraska Press, 2003.

- Robin Ridington, "Omaha Survival: A Vanishing Indian Tribe That Would Not Vanish". American Indian Quarterly. 1987.

- Robin Ridington, "Images of Cosmic Union: Omaha Ceremonies of Renewal". History of Religions. 28 (2): 135-150, 1988

- Robin Ridington, "A Tree That Stands Burning: Reclaiming A Point of View as from the Center". Journal of the Steward Anthropological Society. 17 (1–2): 47–75, 1990 (Forthcoming in Paul Benson, ed. Anthropology and Literature, Urbana: University of Illinois Press.)

- Robin Ridington and Dennis Hastings. Blessing for a Long Time: The Sacred Pole of the Omaha Tribe. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997.

External links

- Irving, Washington. "Washington Irving's Astoria". Astoria or Anecdotes of an Enterprise Beyond the Rocky Mountains.

- National Park Service. "Lewis and Clark Historical Background".

- Campbell, Paulette W. (November–December 2002). "Ancestral Bones Reinterpreting the Past of the Omaha". Humanities, Vol. 23/Number 6. Archived from the original on 2018-01-11. Retrieved 2014-12-23.

- Omaha Indian Music, Library of Congress. Recordings of traditional Omaha music by Francis La Flesche from the 1890s, as well as recordings and photographs from the late 20th century.

- . . 1914.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.