New York Manumission Society

The New York Manumission Society was founded in 1785. The term "manumission" is from the Latin meaning "a hand lets go," inferring the idea of freeing a slave. John Jay, first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States as well as statesman Alexander Hamilton and the lexicographer Noah Webster, along with many slave holders among its founders. Its mandate was to promote gradual emancipation and to advocate for those already emancipated. New York ended slavery in 1827. The Society was disbanded in 1849, after its mandate was perceived to have been fulfilled.[1][2] In the courts and in the legislature the society battled against the slave trade, and for the eventual emancipation of all the slaves in the state. In 1787, they founded the African Free School to teach children of slaves and free people of color, preparing them for life as free citizens. The school produced leaders from within New York's Black community.[1]

Founding

The New-York Manumission Society was founded in 1785, under the full name "The New-York Society for Promoting the Manumission of Slaves, and Protecting Such of Them as Have Been, or May be Liberated". The organization originally comprised a few dozen friends, many of whom were themselves slaveholders at the time. The members were motivated in part by the rampant kidnapping of free blacks from the streets of New York, who were then sold into slavery.[3] Several of the members were Quakers.[1][3]

Meetings were held quarterly.[1] Robert Troup presided over the first meeting,[4] which was held on January 25, 1785, at the home of John Simmons, who had space for the nineteen men in attendance since he kept an inn. Troup, who owned two slaves, and Melancton Smith were appointed to draw up rules, and John Jay, who owned five slaves, was elected as the Society's first president.[3]

At the second meeting, held on February 4, 1785, the group grew to 31 members, including Alexander Hamilton.[2][3]

The Society formed a ways-and-means committee to deal with the difficulty that more than half of the members, including Troup and Jay, owned slaves (mostly a few domestic servants per household). The committee proposed a plan for gradual emancipation: members would free slaves younger than 28 when they reached the age of 35, slaves between 28 and 38 in seven years' time, and slaves over 45 immediately. This proposal failed however, and the committee was dissolved.[3]

Activities

Lobbying and boycotts

John Jay had been a prominent leader in the antislavery cause since 1777, when he drafted a state law to abolish slavery in New York. The draft failed, as did a second attempt in 1785. In 1785, all state legislators except one voted for some form of gradual emancipation. Yet, they could not agree on which civil rights would be given to the slaves once freed.

Jay brought prominent political leaders into the Society, and also worked closely with Aaron Burr, later head of the Democratic-Republicans in New York. The Society started a petition against slavery, which was signed by almost all the politically prominent men in New York, of all parties and led to a bill for gradual emancipation.Burr, in addition to supporting the bill, made an amendment for immediate abolition, which was voted down.

The Society was instrumental in having a state law passed in 1785 prohibiting the sale of slaves imported into the state, and making it easy for slaveholders to manumit slaves either by a registered certificate or by will. In 1788 the purchase of slaves for removal to another state was forbidden; they were allowed trial by jury "in all capital cases;" and the earlier laws about slaves were simplified and restated. The emancipation of slaves by the Quakers was legalized in 1798. At that date, there were still about 33,000 slaves statewide.[5]

The Society organized boycotts against New York merchants and newspaper owners involved in the slave trade. The Society had a special committee of militants who visited newspaper offices to warn publishers against accepting advertisements for the purchase or sale of slaves.

Another committee kept a list of people who were involved in the slave trade, and urged members to boycott anyone listed. According to historian Roger Kennedy:

Those [blacks] who remained in New York soon discovered that until the Manumission Society was organized, things had gotten worse, not better, for blacks. Despite the efforts of Burr, Hamilton, and Jay, the slave importers were busy. There was a 23 percent increase in slaves and a 33 percent increase in slaveholders in New York City in the 1790s.[6]

Accomplishments and legacy

African Free School

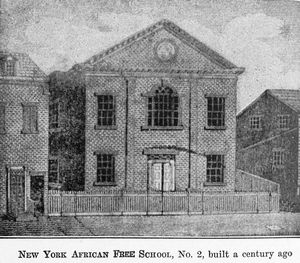

In 1787, the Society founded the African Free School in Williamsburgh, predating its consolidation into Brooklyn.[7] No schools in New York City were open to Black people. Brooklyn was still separate from New York at the time, and in 1815, a resident of the village of Brooklyn opened the first private school for black students at his home in the neighborhood of DUMBO. Peter Croger, a free black man, advertised an “African School” would be open during the day and evening for “those who wish [to] be taught the common branches of education.”[8] Eventually several other schools in other points in Brooklyn were established; African Free School No. 2 in 1839; also Colored School No. 3.[9][10][11]

Litigation

The New York courts and law enforcement zealously enforced the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793. Attempts by the Society to dispute the status or ownership of the detained "fugitives" met with little success.[12] In 1801, under a New York law that prohibited the transportation of slaves through the state, the Society sought to prevent a slave-holding household from disembarking on a sloop for Virginia. However, after city wardens broke up a free-black crowd outside the household's residence, in what press reported as a riot, the Society failed to pursue the freedom suit.[13]

Greater success attended the Society in the courts after it was joined and represented by two exiled United Irishmen, newly admitted to the New York bar, Thomas Addis Emmet and William Sampson. In 1805, in the Topham case, Emmet secured victory for the Society under the federal Slave Trade Act of 1794. He obtained a writ forbidding departure of a ship bound for Africa laden with cargo of rum and other spirits intended for the purchase of slaves.[12][14] Further success attended proceedings in 1806 to prevent a sloop leaving for the south with three free blacks on board, who had been seized to be sold as enslaved.[15]

In The Commissioners of the Almshouse v Alexander Whistelo (1808), involving a black man in a case of paternity, William Sampson, defended the integrity of "interracial" marriage, arguing that ‘‘every man must follow his own pleasure . . . neither philosophy nor religion have forbade such mixtures.’’[16] In Amos and Demis Broad (1809), Sampson succeeded in having a sadistically abused mother and her 3-year-old daughter, manumitted.[17] Sampson had nonetheless to lament that the law kept the woman from testifying on her own behalf: "the silence which fate, for I will not call it law, imposes on the slave who cannot tell us of his own complaint; gagged, and reduced to a state of a dumb brute . . . [is a] weighty obstacle to justice".[18]

Emmet continued to represent the Society, and to defend African Americans against the claims of their former masters, until 1827.[12]

Legislation

Beginning in 1785, the Society lobbied for a state law to abolish slavery in the state, as all the other northern states (except New Jersey) had done. Considerable opposition came from the Dutch areas upstate (where slavery was still popular),[19] as well as from the many businessmen in New York who profited from the slave trade. The two houses passed different emancipation bills and could not reconcile them. Every member of the New York legislature but one voted for some form of gradual emancipation, but no agreement could be reached on the civil rights of freedmen afterwards.[citation needed]

Some measure of success finally came in 1799[20][page needed] when John Jay, as Governor of New York State, signed the Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery into law; however it still ignored the subject of civil rights[which?] for freed slaves.[20][page needed][21][full citation needed] The resulting legislation declared that, from July 4 of that year, all children born to slave parents would be free. It also outlawed the exportation of current slaves to other states. However, the Act held the caveat that the children would be subject to apprenticeship. These same children would be required to serve their mother's owner until age twenty-eight for males, and age twenty-five for females. The law defined the children of slaves as a type of indentured servant, while scheduling them for eventual freedom.[20][page needed]

Another law was passed in 1817:

Whereas by a law of this State, passed the 31st of March, 1817, all slaves born between the 4th of July, 1799, and the 31st of March, 1817 shall become free, the males at 28, and females at 25 years old, and all slaves born after the 31st of March, 1817, shall be free at 21 years old, and also all slaves born before the 4th day of July, 1799 shall be free on the 4th day of July, 1827[22]

The last slaves in New York were emancipated by July 4, 1827; the process was the largest emancipation in North America before 1861.[23] Although the law as written did not set free those born between 1799 and 1817, many still children, public sentiment in New York had changed between 1817 and 1827, enough so that in practice they were set free as well. The press referred to it as a "General Enancipation". An estimated 10,000 enslaved New Yorkers were freed in 1827.[24]

Thousands of freedmen celebrated with a parade in New York. The parade was deliberately held on July 5, not the 4th.[25]

Contrasts to other anti-slavery efforts

The Society was founded to address slavery in the state of New York, while other anti-slavery societies directed their attention to slavery as a national issue. The Quakers of New York petitioned the First Congress (under the Constitution) for the abolition of the slave trade. In addition, Benjamin Franklin and the Pennsylvania Abolition Society petitioned for the abolition of slavery in the new nation, while the New York Manumission Society did not act. Hamilton and others believed that Federal action on slavery would endanger the compromise worked out at the Constitutional Convention, and, by extension, would endanger the new United States.[26]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c d Manumission Society (1785–1849). "New-York Manumission Society records". findingaids.library.nyu.edu. Manumission Society. Retrieved 2024-06-16.

- ^ a b Davis, Dorothy. "New York's Manumission (Free the Slaves!) Society & Its African Free School, 1785–1849". Education Update Online. Archived from the original on 2017-11-23. Retrieved 2006-12-12.

- ^ a b c d e Chernow, Ron (2005). Alexander Hamilton. Penguin Press. pp. 214–215. ISBN 978-0-14-303475-9.

- ^ Foner, Eric (2016). "Columbia and Slavery: A Preliminary Report" (PDF). Columbia and Slavery. Columbia University. pp. 22–25. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-06-20.

- ^ Nelson, Peter (1926). The American Revolution in New York: Its Political, Social and Economic Significance. Albany, The University of the state of New York. p. 237.

- ^ Kennedy, Roger G. (2000). Burr, Hamilton, and Jefferson: A Study in Character. Oxford University Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-19-513055-3.

- ^ New York Historical Society – Manumission (finding aid). New York University Library.

- ^ "HISTORY OF P.S. 67". thedorseyschool.org. THE CHARLES A. DORSEY SCHOOL P.S. 67. 2015. Retrieved 2024-06-16.

- ^ Carl Hancock Rux (2020-09-24). "Black to School: The History of Colored School No.1". myrtleavenue.org. Myrtle Avenue Brooklyn Partnership. Retrieved 2024-06-16.

- ^ "Black Gotham Archive African Free School No. 2". archive.blackgothamarchive.org. Black Gotham Archive at Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities. 2018-07-10. Retrieved 2024-06-16.

- ^ "WritLargeNYC: Colored School No. 2 1839 - present". writlarge.ctl.colombia.edu. Teacher's College Columbia University Center on History and Education Center for Teaching and Learning. 2019. Retrieved 2024-06-16.

- ^ a b c Landy, Craig A. (2014). "Society of United Irishmen Revolutionary and New-York Manumission Society Lawyer: Thomas Addis Emmet and the Irish Contributions to the Antislavery Movement in New York". New York History. 95 (2): 193–222. ISSN 0146-437X.

- ^ Jones, Martha S. (2011). "Time, Space, and Jurisdiction in Atlantic World Slavery: The Volunbrun Household in Gradual Emancipation New York". Law and History Review. 29 (4): (1031–1060) 1032-1033. ISSN 0738-2480.

- ^ Pfander, James (2023-01-01). "Public Law Litigation in Eighteenth Century America: Diffuse Law Enforcement in a Partisan World". Fordham Law Review. 92 (2): (469-497) 483-484.

- ^ White, Shane (1991). Somewhat More Independent: The End of Slavery in New York City, 1770–1810. Cited from p. 174 of the excerpt included in American Slavery, ed. James Miller, San Diego, Greenhaven Press, 2001. University of Georgia Press.

- ^ Harris (2004), p. 110

- ^ Landy, Craig A. (2014). "Society of United Irishmen Revolutionary and New-York Manumission Society Lawyer: Thomas Addis Emmet and the Irish Contributions to the Antislavery Movement in New York". New York History. 95 (2): (193–222) 219–220. ISSN 0146-437X.

- ^ Harris, Leslie M. (2004-08-01). In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626-1863. University of Chicago Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-226-31775-5.

- ^ Parmet, Herbert S.; Hecht, Marie B. (1967). Aaron Burr. New York, Macmillan. p. 76.

- ^ a b c McManus, Edgar J. (1968). History of Negro Slavery in New York. Syracuse University Press.

- ^ Jay, John; Jay, Sarah Livingston (2005). Selected Letters of John Jay and Sarah Livingston Jay. pp. 297–99. ISBN 9780786419555.

- ^ "July 4, 1827.—Jubilee from Domestic Slavery". Evening Post (New York, New York). July 3, 1827. p. 3 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Sudderth, Jake (2002). "John Jay and Slavery". Columbia University.

- ^ "General Slave Emancipation in New-zYork". North Star (Danville, Vermont). July 3, 1827. p. 3 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "From the New York Daily Advertiser, July 6". Hartford Courant (Hartford, Connecticut). July 9, 1827. p. 2 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ McDonald, Forrest (1982). Alexander Hamilton: A Biography. p. 177. ISBN 9780393300482.

Further reading

- Berlin, Ira; Harris, Leslie M., eds. (2005). Slavery in New York. New Press. ISBN 1-56584-997-3.

- Gellman, David N. (2006). Emancipating New York: The Politics of Slavery And Freedom, 1777–1827. Louisiana State Univ. Press. ISBN 0-8071-3174-1.

- Gellman, David N. (2001). "Pirates, Sugar, Debtors, and Slaves: Political Economy and the Case for Gradual Abolition in New York". Slavery & Abolition. 22 (2): 51–68. doi:10.1080/714005193. ISSN 0144-039X. S2CID 143335845.

- Gellman, David N. (2000). "Race, the Public Sphere, and Abolition in Late Eighteenth-century New York". Journal of the Early Republic. 20 (4): 607–636. doi:10.2307/3125009. ISSN 0275-1275. JSTOR 3125009.

- Harris, Leslie M. (August 2001). "African-Americans in New York City, 1626–1863". Department of History Newsletter. Emory University. Archived from the original on 2017-12-03. Retrieved 2006-12-11.

- Harris, Leslie M. (2003). In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626–1863.

- Horton, James Oliver (2004). "Alexander Hamilton: Slavery and Race in a Revolutionary Generation". New-York Journal of American History. 65 (3): 16–24. ISSN 1551-5486.

- Littlefield, Daniel C. (2000). "John Jay, the Revolutionary Generation, and Slavery". New York History. 81 (1): 91–132. ISSN 0146-437X.

- New-York Historical Society (2011). "Race and Antebellum New York City – New York Manumission Society". Examination Days: The New York African Free School Collection. Archived from the original on 2011-05-15.

- Newman, Richard S. (2002). The Transformation of American Abolitionism: Fighting Slavery in the Early Republic. Univ. of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-2671-5.

- Schaetzke, E. Anne (1998). "Slavery in the Genesee Country (Also Known as Ontario County) 1789 to 1827". Afro-Americans in New York Life and History. 22 (1): 7–40. ISSN 0364-2437.

External links

- The Records of the New-York Manumission Society 1785–1849 at the New York Historical Society

- Records of the New-York Manumission Society

- Jay Heritage Center[usurped]

- Memorials of Peter A. Jay