Nelson A. Miles

Nelson A. Miles | |

|---|---|

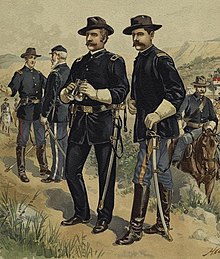

Nelson A. Miles as Commanding General / General-in-Chief of the U.S. Army, 1898 | |

| 1st Military Governor of Puerto Rico | |

| In office July 25, 1898 – October 18, 1898 | |

| President | William McKinley |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | John R. Brooke |

| Commanding General of the U.S. Army | |

| In office October 5, 1895 – August 8, 1903 | |

| President | Grover Cleveland William McKinley Theodore Roosevelt |

| Preceded by | John Schofield |

| Succeeded by | Samuel B. M. Young (as Chief of Staff of the US Army) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | August 8, 1839 Westminster, Massachusetts, US |

| Died | May 15, 1925 (aged 85) Washington, D.C., US |

| Resting place | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | Mary Hoyt Sherman (m. 1868; died 1904) |

| Awards | Medal of Honor |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Union (Civil War) United States |

| Branch/service | Union Army United States Army |

| Years of service | 1861–1865 (Union) 1865–1903 (Army) |

| Rank | Lieutenant General |

| Unit |

|

| Commands |

|

| Battles/wars |

|

Nelson Appleton Miles (August 8, 1839 – May 15, 1925) was a United States Army officer who served in the American Civil War (1861-1865), the later American Indian Wars (1840-1890), and the Spanish–American War, (1898). From 1895 to 1903, Miles served as the last Commanding General of the United States Army, before the office was transformed into the current Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army in 1903.

Early life

Nelson A. Miles was born on his family's farm in Westminster, Massachusetts on August 8, 1839, the son of Daniel Miles and Mary (Curtis) Miles.[1] He was raised and educated in Westminster, and attended the academy run by educator John R. Galt.[2] Having decided on a business career, as a teenager, he moved to Boston, where he worked as a clerk in the John Collamore & Company crockery store.[3]

While living in Boston, he also attended Comer's Commercial College, a business school that offered night courses.[4] With the outbreak of the American Civil War likely, Miles was among several young men in Boston who began to study drill and ceremony, tactics, and strategy under the tutelage of Eugene Salignac, who used the title "colonel" and claimed to be a French army veteran.[1][5]

Civil War

The war started in April 1861; on September 9, 1861, Miles enlisted in the Union Army and was commissioned as a first lieutenant in the 22nd Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, which was organized and commanded by Henry Wilson.[1] He was commissioned a lieutenant colonel of the 61st New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment on May 31, 1862.[1] He was promoted to the rank of colonel after the Battle of Antietam of September 1862.[1]

Other battles he participated in include Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville (during which he was shot in the neck and abdomen), the Overland Campaign, and the final Appomattox Campaign, and Wounded four times in battle. Following the war, two years later, on March 2, 1867, Miles was brevetted a brigadier general in the regular army in recognition of his earlier wartime actions of 1863 at Chancellorsville. He was again brevetted, this time to the rank of major general, for his documented actions at the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House in 1864. Three decades later, he received the Medal of Honor on July 23, 1892, for his gallantry at Chancellorsville. He was appointed brigadier general of volunteers as of May 12, 1864, for the Battles of the Wilderness and Battle of Spotsylvania Court House. Six months after the end of the Civil War, on October 21, 1865, he was appointed a major general of volunteers at the young age of 26.[6] After the war, he was commandant of Fort Monroe, Virginia at the mouth of the Hampton Roads harbor and the southern end of Chesapeake Bay and the James River, where former Confederate President, Jefferson Davis (1808-1889), was held prisoner. During his tenure at Fortress Monroe, General Miles was forced to defend himself against charges that Davis was being mistreated.

Indian Wars

In July 1866, Miles was appointed a colonel in the Regular Army, confirmed by the U.S. Senate.[7] The next year, in April 1867, he was appointed assistant commissioner of the North Carolina branch of the United States War Department's Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, (Freedmen's Bureau), serving under Bureau Commissioner, Brigadier General Oliver O. Howard (1830-1909).[8] On June 30, 1868, he married Mary Hoyt Sherman (daughter of Charles Taylor Sherman, niece of fellow Union Army General William T. Sherman and U.S. Senator John Sherman, and granddaughter of Charles R. Sherman).[9] In March 1869, he became commander of the 5th U.S. Infantry Regiment, a position he held for 11 years.[10]

Miles played a leading role in nearly all of the U.S. Army's campaigns of the later American Indian Wars against the native American Indian tribes of the Great Plains, of the Mid-West, among whom he was known as "Bearcoat" (for his characteristic bearskin fur coat). In 1874–1875, he was a field commander in the force that defeated the Kiowa, Comanche, and the Southern Cheyenne along the upper Red River of the South. Between 1876 and 1877, he participated in the campaign that scoured the Northern Plains after 5 companies of the 7th U.S. Cavalry Regiment under the command of Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer were massacred at the Battle of the Little Big Horn in June 1876, and forced the Lakota Sioux tribe under chiefs Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse and their native allies onto designated federal Indian reservations. In the winter of 1877, he drove his bluecoat mounted troops on a forced march across the eastern Montana Territory to intercept and stop the Nez Perce tribal band led by Chief Joseph (1840-1904), after the Nez Perce War, heading north to cross the border into British Canada. For the rest of his career, General Miles would quarrel with General Oliver O. Howard (1830-1909), who also led the pursuing expedition over taking credit for Chief Joseph's capture. Later while on the Yellowstone River, he developed expertise with the use of the heliograph for sending long-distance communications signals utilizing ancient principles of sunlight and mirrors, establishing a 140-mile-long (230 km) line of stations with heliographs connecting far-flung military posts of Fort Keogh and Fort Custer, in the Montana Territory in 1878.[11][12] The heliographs were supplied by Brig. Gen. Albert J. Myer (1828-1880), of the U.S. Army's Signal Corps.[13]

In December 1880, Miles was promoted to brigadier general in the Regular Army. He was then assigned to command the military Department of the Columbia (1881–1885) in Oregon and the Washington Territory, and subsequently the Department of Missouri (1885–1886). In 1886, Miles replaced General George R. Crook (1828-1890), as commander of forces fighting against Geronimo (1829-1909), a Chiricahua Apache renegade chief / guerrilla fighter leader, in the military's Department of Arizona in the old Arizona Territory in the Southwest. General Crook had relied heavily on Apache scouts in his efforts to capture Geronimo. Instead, Miles relied instead on white regular cavalry troops, who eventually traveled 3,000 miles (4,800 km) without success as they tracked Geronimo through the tortuous Sierra Madre Mountains of neighboring northern Mexico. Finally, young First Lieutenant Charles B. Gatewood (1853-1896), who had studied Apache culture and ways, succeeded in meeting with and negotiating a surrender of the war chief at a subsequent meeting arranged and held with General Miles, under the terms of which Geronimo and his few remaining followers agreed to temporarily spend two years in exile on a Florida reservation far to the east. Geronimo agreed on these terms, being unaware of the real plot behind the negotiations (that there was no real intent to let them go back to their native lands in Arizona and New Mexico). The exile included even the Chiricahuas Apache scouts who had worked for the army, in violation of Miles' original agreement with them. Miles denied Lt. Gatewood any credit for the negotiations and had him transferred far north to the Dakota Territory. During this campaign, Miles' special signals unit used the heliograph extensively, proving its worth in the field.[13] The special signals unit was under the command of Captain W. A. Glassford.[13] In 1888, Miles became the commander of the Army's Military Division of the Pacific and the Department of California, headquartered at The Presidio in San Francisco.

Two years later in April 1890, Miles was promoted to major general in the Regular Army and became the commander of the Military Division of the Missouri. The Ghost Dance movement of the Lakota Sioux people, which started in 1889, led to the Pine Ridge Campaign of the so-called Ghost Dance War and General Miles being brought back into the field. During the campaign, he commanded U.S. Army troops stationed near the several federal Indian reservations in the new state of South Dakota and hoped that Lakota chief Sitting Bull could be peacefully removed from the Standing Rock Indian Reservation. However, on December 15, 1890, Chief Sitting Bull was killed by Indian agency police attempting to arrest him, and 14 days later on December 29th, American cavalry troops surrounded and massacred hundreds of Lakota Sioux at Wounded Knee. Miles was not directly involved in the tragic massacre, and was critical of the Army's commanding officer of the reconstituted / reorganized and ill-fated 7th U.S. Cavalry Regiment in the field, Colonel James W. Forsyth (1833-1906). Just two days after the massacre, Miles wrote to his wife, describing it as "the most abominable criminal military blunder and a horrible massacre of women and children".[14] After his retirement from the Army a decade later, he fought for compensation payments to the Lakota Sioux survivors of the massacre. Overall however, he believed that the United States federal government should have authority over the native Indians, with the Lakota under military control.

Spanish–American War and later life

In his capacity as commander of the Department of the East from 1894 to 1895, Miles commanded the troops mobilized to put down the Pullman strike riots.[15] He was named Commanding General of the United States Army in 1895, a post he held during the Spanish–American War. Miles commanded forces at Cuban sites such as Siboney.

After the surrender of Santiago de Cuba by the Spaniards, he led the invasion of Puerto Rico,[16] landing in Guánica in what is known as the Puerto Rican Campaign. He served as the first head of the military government established on the island, acting as both heads of the army of occupation and administrator of civil affairs. Upon returning to the United States, Miles was a vocal critic of the Army's quartermaster general, Brigadier General Charles P. Eagan, for providing rancid canned meat to troops in the field during what was known as the Army beef scandal. He was promoted to the rank of lieutenant general in 1900 based on his performance in the war. Miles was an opponent of the Philippine–American War and supported an inquiry into the brutality of American troops in the Philippines. In response, President Roosevelt called Miles a hypocrite and reminded him of his complicity in the Wounded Knee massacre. Miles would release his own report on US atrocities in the Philippines to the public. He condemned the use of concentration camps and said that the use of torture was widespread and was undertaken with the knowledge of some senior officers.[17]

To show that he was still physically able to command, on July 14, 1903, less than a month before his 64th birthday, General Miles rode the 90 miles from Fort Sill to Fort Reno, Oklahoma, in eight hours' riding time (10 hrs 20 mins total), in temperatures between 90 and 100 °F (32 and 38 °C). The distance was covered on a relay of horses stationed at 10-mile intervals; the first 30 miles were covered in 2 hours, 25 minutes. This was the longest horseback ride ever made by a commanding general of the army.[18]

Called a "brave peacock" by President Theodore Roosevelt,[citation needed] Miles nevertheless retired from the army in 1903 upon reaching the mandatory retirement age of 64. Upon his retirement, the office of Commanding General of the United States Army was abolished by an Act of Congress and the Army Chief of Staff system was introduced. A year later, standing as a presidential candidate at the Democratic National Convention, he received a handful of votes.[citation needed] The Prohibition Party was going to give him their nomination, but an hour before balloting he sent a telegram to the convention stating that he did not want the nomination which went to Silas C. Swallow instead.[19] When the United States entered World War I in 1917, the 77-year-old general offered to serve, but President Woodrow Wilson turned him down.[citation needed]

Miles died in 1925 at the age of 85 from a heart attack while attending the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus in Washington, D.C., with his grandchildren. First Lady Grace Coolidge was also in attendance at the circus that day, and upon arriving at the showgrounds the general told circus owner John Ringling that he never missed a circus.[20] Nelson was one of the last surviving general officers who served during the Civil War on either side.[21] He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery in the Miles Mausoleum. It is one of only two mausoleums within the confines of the cemetery. George Burroughs Torrey painted his portrait.

Military awards

- Medal of Honor

- Civil War Campaign Medal

- Indian Campaign Medal

- Spanish Campaign Medal

- Army of Puerto Rican Occupation Medal

Medal of Honor citation

Rank and Organization:

- Colonel, 61st New York Infantry. Place and date: At Chancellorsville, Va., May 3, 1863. Entered service at: Roxbury, Mass. Birth: Westminster, Mass. Date of issue: July 23, 1892.

Citation:

- Distinguished gallantry while holding with his command an advanced position against repeated assaults by a strong force of the enemy; was severely wounded.[22]

Memberships

General Miles was a member of several hereditary and military societies, including the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS), serving as Commander-in-Chief from 1919 to 1925, the Grand Army of the Republic, Sons of the American Revolution and the Military Order of Foreign Wars. He was also an honorary member of the Massachusetts Society of the Cincinnati. He was also a member of the Union League Club of New York, where his portrait hung in the main bar area for many years.

Legacy

Miles City, Montana is named in his honor,[23] as is Miles Street and the Miles Neighborhood in Tucson, Arizona. Miles Canyon on the Yukon River near Whitehorse, Yukon, was named after him in 1883 by Lt. Frederick Schwatka during his exploration of the river system. A steamship, General Miles, was likely named for him. Nelson M. Holderman, himself a Medal of Honor recipient, was also named after Miles. Fort Miles at Cape Henlopen near Lewes, Delaware, was named for Miles on 3 June, 1941.

Miles' legacy as an Indian fighter has seen him portrayed by Kevin Tighe in the film Geronimo: An American Legend, by Hugh O'Brian in the film Gunsmoke: The Last Apache, and by Shaun Johnston in the film adaptation of Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. There is a bust of General Miles in the Massachusetts State Capitol in Boston. General Miles' son, Sherman Miles (1882–1966), was a career Army officer who graduated from West Point in 1905 and rose to the rank of major general during World War II. His daughter Cecelia was the wife of Colonel Samuel Reber II, and the mother of Miles and Samuel Reber III.

Dates of rank

| Insignia | Rank | Component | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Lieutenant | 22nd Massachusetts Infantry | 9 September 1861 | |

| Lieutenant Colonel | 61st New York Infantry | 31 May 1862 | |

| Colonel | 61st New York Infantry | 30 September 1862 | |

| Brigadier General | Volunteers | 12 May 1864 | |

| Brevet Major General | Volunteers | 25 August 1864 | |

| Major General | Volunteers | 21 October 1865 | |

| Colonel | 40th Infantry, Regular Army | 28 July 1866 | |

| Brevet Major General | Regular Army | 2 March 1867 | |

| Colonel | 5th Infantry, Regular Army | 15 March 1869 | |

| Brigadier General | Regular Army | 15 December 1880 | |

| Major General | Regular Army | 5 April 1890 | |

| Lieutenant General | Regular Army | 6 June 1900 | |

| Lieutenant General | Retired List | 8 August 1903 |

See also

- List of Medal of Honor recipients

- List of American Civil War Medal of Honor recipients: M–P

- List of American Civil War generals (Union)

- List of Massachusetts generals in the American Civil War

Notes

- ^ a b c d e Encyclopedia of Massachusetts, Biographical‒Genealogical. New York: The American Historical Society. 1916. p. 7 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Patriotic Leaders of To-Day: Lt.-Gen. Nelson A. Miles". The Guardian of Liberty. Chicago: The Guardians of Liberty. December 1917. p. 143 – via Google Books.

- ^ The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography. Vol. IX. New York: James T. White & Company. 1899. p. 26 – via Google Books.

- ^ Gates, Merrill E., ed. (1906). Men of Mark in America. Vol. II. Washington, D.C.: Men of Mark Publishing Company. p. 176 – via Google Books.

- ^ Miller, Richard F. (2005). Harvard's Civil War: A History of the Twentieth Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. Hanover, New Hampshire: University Press of New England. pp. 19–20. ISBN 978-1-5846-5505-3 – via Google Books.

- ^ Eicher, p. 389.

- ^ U.S. Senate (1887). Journal of the Executive Proceedings of the Senate of the United States. Vol. XV, Part I. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 42 – via Google Books.

- ^ Smithsonian Online Virtual Archives. "Historical Note: The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands". Records of the Assistant Commissioner for the State of North Carolina Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, 1865–1870. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- ^ Wooster, Robert (1996). Nelson A. Miles and the Twilight of the Frontier Army. University of Nebraska Press. pp. 50–51. ISBN 0803297750.

- ^ "Gen. Miles and the Signal Service". Fitchburg Sentinel. Fitchburg, MA. November 19, 1880. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Signal Service Station on Mount Hood". Daily Alta California. September 20, 1884. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- ^ Reade, Lt. Philip (January 1880). "About Heliographs". The United Service. 2: 91–108. Retrieved June 21, 2011.

- ^ a b c Coe, Lewis (1993) The Telegraph: A History of Morse's Invention and its Predecessors in the United States McFarland, Jefferson, N.C., p. 10, ISBN 0-89950-736-0

- ^ DeMontravel, Peter R. (1998). A Hero to His Fighting Men. Kent State University Press. p. 206. ISBN 9780873385947.

- ^ The Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars: A Political, Social, and Military History, Volume 1, p. 400

- ^ "Invasion of Puerto Rico". The Goldfields Morning Chronicle (Coolgardie, WA : 1896–1898). July 19, 1898. Retrieved October 29, 2019.

- ^ Ranson, Edward (1965). "Nelson A. Miles as Commanding General, 1895–1903". Military Affairs. 29 (4): 179–200. doi:10.2307/1984406. ISSN 0026-3931. JSTOR 1984406.

- ^ See newspaper reports from Washington, D.C. (Showing off his Stamina. General Miles making 90-mile horseback ride) and Kansas City, MO (General Miles made it in Triumph), July 14, 1903. Hot off the Press Long Riders Guild Academic Foundation. Retrieved October 11, 2015.

- ^ "Dr. Swallow Nominated". The Lancaster Examiner. July 2, 1904. p. 1. Archived from the original on December 18, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Gen. Nelson A. Miles Diesat Circus; Indian Fighter, 85, Falls Lifeless While Viewing Pageant, with Mrs. Coolidge Near by. Civil War "Boy General" Won Congressional Medal – Fought Also in Spanish-American War – of Family of Soldiers". The New York Times.

- ^ Warner, pp. 323–324, states that Miles was the "last survivor of the full rank major generals of Civil War vintage" and of all general officers, was outlasted only by John R. Brooke (died 1926) and Adelbert Ames (died 1933).

- ^ "MILES, NELSON A., Civil War Medal of Honor recipient". American Civil War website. November 8, 2007. Retrieved November 8, 2007.

- ^ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 208.

- ^ Heitman, Francis B. (1903). Historical Register and Dictionary of the United States Army, 1789–1903, Vol. 1. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. pp. 708–709.

References

- DeMontravel, Peter R. A Hero to His Fighting Men, Nelson A. Miles, 1839–1925. Kent, OH: The Kent State University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-87338-594-2.

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher. Civil War High Commands. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

- Miles, Nelson Appleton. Personal Recollections and Observations of General Nelson A. Miles. Chicago: Werner Co., 1896. OCLC 84296302.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964. ISBN 0-8071-0822-7.

- Greene, Jerome. American Carnage: Wounded Knee, 1890. University of Oklahoma Press, 2014. ISBN 978-0806144481

Further reading

- Freidel, Frank. The Splendid Little War. Short Hills, NJ: Burford Books, 1958. ISBN 0-7394-2342-8.

- Greene, Jerome A. Yellowstone Command: Colonel Nelson A. Miles and the Great Sioux War, 1876–1877. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2006, 1991. ISBN 080613755X

External links

- Works by Nelson Appleton Miles at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Nelson A. Miles at the Internet Archive

- Commanding Generals and Chiefs of Staff Archived May 5, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- Nelson A. Miles Collection Archived May 7, 2013, at the Wayback Machine US Army Heritage and Education Center, Carlisle, Pennsylvania

- David Leighton, "Tucson Street Smarts: Miles Street named for famed general," Arizona Daily Star, March 19, 2013

- Guide to the Nelson Appleton Miles Collection 1886 at the University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center