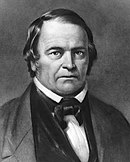

Nelson H. Barbour

| Part of a series on |

| Adventism |

|---|

|

|

|

Nelson H. Barbour (August 21, 1824 – August 30, 1905) was an Adventist writer and publisher, best known for his association with—and later opposition to—Charles Taze Russell.

Life

Nelson H. Barbour was born in Throopsville, New York, August 21, 1824, and died in Tacoma, Washington, August 30, 1905.[1]

Barbour was the son of David Barbour and the grandson of Friend Barbour. Both the family and official documents use the spelling "Barbour" and its alternative spelling "Barber".

He was related to a number of prominent New Yorkers including Dio Lewis. He attended Temple Hill Academy at Geneseo, New York, from 1839 to 1842. While at Temple Hill he also studied for the Methodist Episcopal ministry with an Elder Ferris, possibly William H. Ferris.[2]

Barbour was introduced to Millerism through the efforts of a Mr. Johnson who lectured at Geneseo, in the winter of 1842. Barbour associated with other Millerites living in that area. These included Owen Crozier, William Marsh, Daniel Cogswell and Henry F. Hill. Cogswell later became president of the New York Conference of the Advent Christian Church. Hill became a prominent author associated with the Evangelical Adventists.

Adventists in the Geneseo area met in Springwater to await the second coming in 1843. Their disappointment was profound, and Barbour suffered a crisis of faith. He later wrote: "We held together until the autumn of 1844. Then, as if a raft floating in deep water should suddenly disappear from under its living burden, so our platform went from under us, and we made for shore in every direction; but our unity was gone, and, like drowning men, we caught at straws."[3]

Barbour pursued a medical career, becoming a medical electrician—a therapist who treated disease through the application of electric current, which was seen as a valid therapy at the time.

He went to Australia to prospect for gold, returning via London in 1859. Barbour claimed to have preached during his time in Australia.[4] A ship-board discussion with a clergyman reactivated his interest in Bible prophecy. He consulted books on prophetic themes at the British Library and became convinced that 1873 would mark the return of Christ, based on ideas advanced by others since at least as early as 1823.

Returning to the United States, Barbour settled in New York City, continuing his studies in the Astor Library. When fully convinced, he wrote letters and visited those who he felt might best spread his message, though few were interested.

Barbour became an inventor and associated with Peter Cooper, the founder of Cooper Union. He patented several inventions. By 1863 he was in medical practice, dividing his time between Auburn and Rochester, New York. He returned to London in 1864 to demonstrate one of his inventions. He used his association with other inventors and scientists to spread his end-times doctrine, and some of his earliest associates in that belief were inventors and physicians.

He published something[clarification needed] as early as 1868, though it has been lost.[5] In 1871 he wrote and published a small book entitled Evidences for the Coming of the Lord in 1873, or The Midnight Cry, which had two printings. Barbour's articles also appeared in the magazine The World’s Crisis and Second Advent Messenger.

As 1873 approached, various groups began advocating it as significant. Jonas Wendell led one, another centered on the magazine The Watchman's Cry[clarification needed], and the rest were associated with Barbour. British Barbourites were represented by Elias H. Tuckett, a clergyman. Many gathered at Terry Island to await the return of Christ in late 1873. Barbour and others looked to the next year, which also proved disappointing.

Led by Benjamin Wallace Keith, an associate of Barbour's since 1867, the group adopted the belief in a two-stage, initially invisible presence. They believed that Christ had indeed come in 1874 and would soon become visible for judgments. Barbour started a magazine in the fall of 1873 to promote his views, calling it The Midnight Cry. It was first issued as a pamphlet, with no apparent expectation of becoming a periodical. He quickly changed the name to Herald of the Morning, issuing it monthly from January 1874.

showing Barbour as Editor.

In December 1875, Charles Taze Russell, then a businessman from Allegheny, received a copy of Herald of the Morning. He met the principals in the Barbourite movement and arranged for Barbour to speak in Philadelphia in 1876. Barbour and Russell began their association, during which Barbour wrote the book Three Worlds (1877) and published a small booklet by Russell entitled Object and Manner of Our Lord's Return. Beginning in 1878, they each wrote conflicting views on Ransom and Atonement doctrine. By May 3, 1879, Russell wrote that their "points of variance seem to me to be so fundamental and important that… I feel that our relationship should cease." In a May 22, 1879 letter to Barbour, Russell explicitly resigned: "Now I leave the 'Herald' with you. I withdraw entirely from it, asking nothing from you… Please announce in next No. of the 'Herald' the dissolution and withdraw my name [as assistant editor on the masthead]." In July 1879, Russell began publishing Zion's Watch Tower, the principal journal of the Bible Student movement. Several years after Russell's death, the magazine became associated with Jehovah's Witnesses and was renamed The Watchtower.[6]

By 1883 Barbour abandoned belief in an invisible presence and returned to more standard Adventist doctrine. He had organized a small congregation in Rochester in 1873.[7] At least by that year he left Adventism for Age-to-Come faith, a form of British Literalism. He changed the name of the congregation to Church of the Strangers. In later years the congregation associated with Mark Allen's Church of the Blessed Hope and called themselves Restitutionists. A photo of Nelson Barbour appeared in the Rochester Union and Advertiser in October 1895.

Barbour intermittently published Herald of the Morning until at least 1903, occasionally issuing statements critical of C. T. Russell. He wrote favorably though cautiously that he was persuaded to believe that 1896 was the date for Christ's visible return, an idea that had grown out of the Advent Christian Church. The last date set by Barbour for Christ's return was 1907.

By the time of his death the Rochester church numbered about fifty, with very minor interest elsewhere. In 1903 Barbour participated in a conference on Mob Spirit in America. He advocated the establishment of a predominately black state in the Southwestern United States.

Barbour died while on a trip to the west in 1905 of "exhaustion".[8]

After his death some of his articles from The Herald of the Morning were collected and published in book form as Washed in His Blood (1908).

Biography

The Rochester Union and Advertiser for October 5, 1895, page 12, offers the following information on Nelson Barbour:

Nelson H. Barbour was born at Toupsville, three miles from Auburn, N.Y., in 1824. At an early age the family moved to Cohocton, Stueben County, N. Y. From the age of 15 to 18, he attended school at Temple Hill Academy, Genseco, New York; at which place he united with the Methodist Episcopal Church, and began a preparation for the ministry under elder Ferris. Having been brought up among Presbyterians, however, and having an investigating turn of mind, instead of quietly learning Methodist theology he troubled his teacher with questions of election, universal salvation, and many other subjects, until it was politely hinted that he was more likely to succeed in life as a farmer than as a clergyman. But his convictions were strong that he must preach the gospel even if he could not work in any theological harness. And at 19, he began his life work as an independent preacher. Since which, all that is worth reporting in his life is inseparable from his theological growth. He could not believe in an all wise and loving Father, permitting the fall; then leaving man's eternal destiny to a hap-hazard scramble between a luke-warm [sic] Church and a zealous devil. On the contrary he believed the fall was permitted for a wise purpose; and that God has a definite plan for man, in which nothing is left to chance or ignorance.

Mr. Barbour believes that what he denominated the present babel of confusion in the churches is the result of false teaching and the literal interpretation of the parables.

The Church of the Strangers was organized in 1879. Mr. Barbour has preached in England, in several Australian colonies, in Canada, and many states of the Union. For the past twenty-two years he has published the Herald of the Morning in this city; claiming that in his 'call' to preach, he confered [sic] not with flesh and blood. Nor was he called to convert the world; but independent of creed, to search for the truth "as it is in Jesus," the "second man Adam," believing that the restored faith is a precurser [sic] of the millenium [sic] and "Times of restitution of all things."

References

- ^ An 1870 patent application by Barbour gives his middle name as Horatio. The New York Grave Index gives his name as Nelson Horatio Barbour. His middle name appears in the United States Library of Congress as Homer. B. Woodcroft: Alphabetical Index of Patentees and Applicants of Patents for Invention for the year 1870, page 79. Schulz & deVienne: Nelson Barbour: The Millennium's Forgotten Prophet, 2009, p. 4.

- ^ Elder Ferris' probable identity with William H. Ferris is discussed in Schulz & de Vienne, Nelson Barbour: The Millennium's Forgotten Prophet, pp. 11–12

- ^ Barbour, N. H.: Evidences for the Coming of the Lord in 1873, or The Midnight Cry, 1871, p. 26.

- ^ Rochester Union and Advertiser.

- ^ Letter from W. Valentine to Nelson Barbour & Barbour's reply: Herald of the Morning, August 1875, p. 47.

- ^ "Proclaiming the Lord's Return (1870–1914)", Jehovah's Witnesses—Proclaimers of God's Kingdom, p. 48.

- ^ Barbour discusses the move in the May 1879 Herald of the Morning.

- ^ Schulz & de Vienne, citing various obituaries including the original Washington State Death Record and The Auburn, New York, Citizen of October 20, 1905.

Further reading

- Penton, M. J. (1983). "The Eschatology of Jehovah's Witnesses: A Short, Critical Analysis". In Bryant, M. Darrol; Dayton, Donald W. (eds.). The Coming Kingdom: Essays in American Millennialism and Eschatology. Barrytown, New York: International Religious Foundation. pp. 169–208. ISBN 0-913757-00-4. OCLC 10881800.

External links

- Three Worlds Archived 2006-03-20 at the Wayback Machine, written by Barbour, and financed by Russell in 1877.

- Evidences for the Coming of the Lord in 1873, or The Midnight Cry Archived 2006-07-07 at the Wayback Machine Written by Barbour in 1871.

- Message to Herald of the Morning subscribers Archived 2019-12-31 at the Wayback Machine 1879 Pittsburgh, Pa; Zion's Watch Tower and Herald of Christ's Presence, July 1, 1879, Supplement

- Washed in the Blood Published anonymously but listed in the library of Congress card catalog as written by Nelson H. Barbour.

- Herald of the Morning Assorted Issues from 1875 to 1880.