Names of the Croats and Croatia

The non-native name of Croatia (Croatian: Hrvatska) derives from Medieval Latin Croātia, itself a derivation of the native ethnonym of Croats, earlier *Xъrvate and modern-day Croatian: Hrvati. The earliest preserved mentions of the ethnonym in stone inscriptions and written documents in the territory of Croatia are dated to the 8th-9th century, but its existence is considered to be of an earlier date due to lack of preserved historical evidence as the arrival of the Croats is historically and archaeologically dated to the 6th-7th century. The names of the Croats, Croatia and Croatian language with many derivative toponyms, anthroponyms and synonyms became widespread all over Europe.

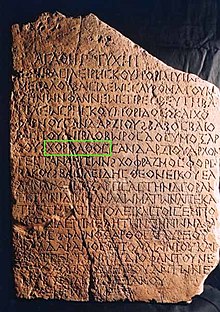

There exist many and various linguistical and historical theories on the origin of the ethnonym. It is usually considered not to be of Slavic but rather Iranian language origin. According to the most probable Iranian theory, the Proto-Slavic *Xъrvat- < *Xurwāt- derives from Proto-Ossetian / Alanian *xurvæt- or *xurvāt-, in the meaning of "one who guards" ("guardian, protector"), which was borrowed before the 7th century. The relation to the 3rd-century Scytho-Sarmatian form Khoroáthos (alternate forms comprise Khoróatos and Khoroúathos) attested in the Tanais Tablets, near the border of present day Ukraine and European Russia, although possible remains uncertain.

Earliest record

In 2005, it was archaeologically confirmed that the ethnonym Croatorum (half-preserved) is mentioned for the first time in a church inscription found in Bijaći near Trogir dated to the end of the 8th or early 9th century.[1]

The oldest known preserved stone inscription with full ethnonym "Cruatorum" is the 9th-century Branimir inscription found in Šopot near Benkovac, in reference to Duke Branimir, dated between 879 and 892, during his rule.[2] The inscription mentions:

- BRANIMIRO COM [...] DUX CRVATORVM COGIT [...]

The Latin charter of Duke Trpimir, dated to 852, has been generally considered the first attestation of the ethnonym "Chroatorum". However, the original of this document has been lost, and copy has been preserved in a 1568 transcript. Lujo Margetić proposed in 2002 that the document is in fact of legislative character, dating to 840.[3]

In the Trpimir charter, it is mentioned:

- Dux Chroatorum iuvatus munere divino [...] Regnum Chroatorum

The monument with the earliest writing in Croatian containing the native ethnonym variation xъrvatъ (IPA: [xŭrvaːtŭ]) is the Baška tablet from 1100, which reads: zvъnъmirъ kralъ xrъvatъskъ ("Zvonimir, king of Croats").[4]

Etymology

The exact origin and meaning of the ethnonym Hr̀vāt (Proto-Slavic *Xъrvátъ,[5][6] or *Xurwātu[7]) is still subject to scientific disagreement.[8] The first etymological thesis about the name of the Croats stems from Constantine Porphyrogennetos (tenth century), who connected the different names of the Croats, Βελοχρωβάτοι and Χρωβάτοι (Belokhrobatoi and Khrobatoi), with the Greek word χώρα (khṓra, "land"): "Croats in Slavic language means those who have many lands". In the 13th century, Thomas the Archdeacon considered that it was connected with the name of inhabitants of the Krk isle, which he gave as Curetes, Curibantes. In the 17th century, Juraj Ratkaj found a reflexion of the verb hrvati (se) "to wrestle" in the name.[9] A more contemporary theory believes that it might not be of native Slavic lexical stock, but a borrowing from an Iranian language.[10][11][12][13][14] Common theories from the 20th and 21st centuries derive it from an Iranian origin, the root word being a third-century Scytho-Sarmatian form attested in the Tanais Tablets as Χοροάθος (Khoroáthos, alternate forms comprise Khoróatos and Khoroúathos).[4][10][15]

In the 19th century, many different derivations were proposed for the Croatian ethnonym:

- Josef Dobrovský believed it to be linked to the root *hrev "tree", whereas Johann Kaspar Zeuss linked it to *haru "sword";

- Sylwiusz Mikucki connected it with Old-Indian šarv- "strike";

- Pavel Jozef Šafárik derived it from xrъbъtъ, xribъtъ, xribъ "ridge, highlanders", whereas Franz Miklosich said it derived from hrъv (hrŭv) "dance";

- Đuro Daničić considered its root to be *sar- "guard, protect";

- Fyodor Braun saw the German Harfada (Harvaða fjöllum from Hervarar saga ok Heiðreks), which would be the German name of the Carpathian Mountains, as the origin of an intermediate form Harvata;[16]

- Rudolf Much connected it to a Proto-Germanic word hruvat- "horned", or – as Z. Gołąb later proposed common noun *xъrvъ//*xorvъ "armor" as a prehistorical loanword from Germanic *hurwa-//*harwa- "horn-armor"; derivatives *xъrvati sę//*xъrviti sę "get armored, defend oneself" – "warriors clad with horn-armor", as a self-designation or exonym;[17][18]

- Henry Hoyle Howorth,[19] J. B. Bury,[20] Henri Grégoire,[21] considered that it derives from the personal name of Kubrat, the leader of the Bulgars and founder of Old Great Bulgaria.

The 20th century gave rise to many new theories regarding the origin of the name of the Croats:

- A. I. Sobolevski derived it from the Iranian words hu- "good", ravah- "space, freedom" and suffix -at-;

- Grigoriĭ Andreevich Ilʹinskiĭ derived it from *kher- "cut", as seen in the Greek word kárkharos "sharp", kharah "tough, sharp", and xorbrъ "brave";

- Hermann Hirt saw a connection with the name of a Germanic tribe Harudes (Χαροῦδες);

- Leopold Geitler, Josef Perwolf, Aleksander Brückner, Tadeusz Lehr-Spławiński and Heinz Schuster-Šewc linked the root hrv- to Slovak charviti sa "to oppose, defend" or via skъrv-/xъrv- to the Lithuanian šárvas "armor" and šarvúotas "armed, cuirassier", with suffix -at emphasizing the characteristic, giving the meaning of a "well armed man, soldier";

- Karel Oštir considered valid a connection with an unspecified Thraco-Illyrian word xъrvata- "hill";

- Max Vasmer first considered it as a loanword from Old-Iranian, *(fšu-)haurvatā- "shepherd, cattle guardian" (formed of Avestan pasu- "cattle" and verb haurvaiti "guard"), later also from Old-Iranian hu-urvatha- "friend" (also accepted by N. Zupanič).[9]

- Niko Zupanič additionally proposed Lezgian origin from Xhurava (community) and plural suffix -th, meaning "municipalities, communities".[22]

- M. Budimir saw in the name a reflexion of Indo-European *skwos "gray, grayish", which in Lithuanian gives širvas;

- S. K. Sakač linked it with the Avestan name Harahvaitī, which once signified the southwestern part of modern Afghanistan, the province Arachosia.[5] "Arachosia" is the Latinized form of Ancient Greek Ἀραχωσία (Arachosíā), in Old Persian inscriptions, the region is referred to as Harahuvatiš.[23] In Indo-Iranian it actually means "one that pours into ponds", which derives from the name of the Sarasvati River of Rigveda.[24] However, although the somewhat suggestive similarity, the connection to the name of Arachosia is etymologically incorrect;[24][15]

- G. Vernadsky considered a connection to the Chorasmí from Khwarezm,[25] while F. Dvornik a link to the Krevatades or Krevatas located in the Caucasus mentioned in the De Ceremoniis (tenth century).[25]

- V. Miller saw in the Croatian name the Iranian hvar- "sun" and va- "bed", P. Tedesco had a similar interpretation from Iranian huravant "sunny", while others from the Slavic god Khors;[26]

- Otto Kronsteiner suggested it might be derived from Tatar-Bashkir *chr "free" and *vata "to fight, to wage war";[5]

- Stanisław Rospond derived it from Proto-Slavic *chorb- + suffix -rъ in the meaning of "brave";

- Oleg Trubachyov derived it from *xar-va(n)t (feminine, rich in women, ruled by women), which derived from the etymology of Sarmatians name,[13][27] the Indo-Aryan *sar-ma(n)t "feminine", in both Indo-Iranian adjective suffix -ma(n)t/wa(n)t, and Indo-Aryan and the Indo-Iranian *sar- "woman", which in Iranian gives *har-.[27]

Among them most taken into account were (1) the Germanic derivation from the Carpathian Mountains which is by now considered as obsolete; (2) the Slavic and Germanic derivations about "well armed man"/"warriors clad with horn-armor" indicating that they stood out from the other Slavs in terms of weapons and armour, but it is not convincing because no other Slavic tribe is named after the objects of material culture. Etymologically the first was a Lithuanian borrowing from much younger Middle High German sarwes, while the second with hypothetical *hurwa-//*harwa- argues a borrowing from Proto-Germanic dialect of the Bastarnae in the sub-Carpathian or Eastern Carpathian region which isn't preserved in any Slavic or Germanic language; (3) and the prevailing Iranian derivations, Vasmer's *(fšu-)haurvatā- ("cattle guardian") and Trubachyov's *xar-va(n)t (feminine, rich in women, ruled by women).[10][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36]

While linguists and historians agreed or with Vasmer's or Trubachyov's derivation, according to Tadeusz Lehr-Spławiński and Radoslav Katičić the Iranian theses doesn't entirely fit with the Croatian ethnonym, as according to them, the original plural form was Hrъvate not Hъrvate,[37] and the vowel "a" in the Iranian harvat- is short, while in the Slavic Hrъvate it is long among others.[30][38] Katičić concluded that of all the etymological considerations the Iranian is the least unlikely.[8][10][38][39] Ranko Matasović also considered it of Iranian origin,[13] but besides confirming original forms as *Xъrvátъ (sl.) and *Xъrvate (pl.), dismissed Trubachyov's derivation because was semantically and historically completely unfounded, and concluded that the only derivation which met the criteria of adaptation of Iranian language forms to Proto-Slavic, as well as historical and semantical plausibility, it is the Vasmer's assumption but with some changes, as the Proto-Slavic *Xъrvat- < *Xurwāt- comes from Proto-Ossetian / Alanian *xurvæt- or *xurvāt-, in the meaning of "one who guards" ("guardian, protector"), which was borrowed before the 7th century, and possibly was preserved as a noun in Old Polish charwat (guard).[40] Matasović considered its relation to the 3rd-century name Khoroathos from Tanais as a coincidence.[41]

The Medieval Latin C(h)roatae and Greek form Khrōbátoi are adaptations of Western South Slavic plural pronunciation *Xərwate from late 8th and early 9th century, and came to Greek via Frankish source.[42] To the Proto-Slavic singular form are closest Old Russian xorvaty (*xъrvaty) and German-Lusatian Curuuadi from 11th and 12th century sources, while the old plural form *Xъrvate is correctly reflected in Old Russian Xrovate, Xrvate, Church Slavonic xarьvate and Old Croatian Hrvate.[43] The form Charvát in Old Czech came from Croatian-Chakavian or Old Polish (Charwaty).[44] The Croatian ethnonym Hr̀vāt (sl.) and Hrváti (pl.) in the Kajkavian dialect also appear in the form Horvat and Horvati, while in the Chakavian dialect in the form Harvat and Harvati.[45]

Distribution

Croatian place names can be found in northern Slavic regions such as Moravia (Czech Republic) and Slovakia, Poland, along the river Saale in Germany, in Austria and Slovenia, and in the south in Greece, Albania among others.[46]

In Germany along Saale river there were Chruuati near Halle in 901 AD, Chruuati in 981 AD,[47] Chruazis in 1012 AD,[47] Churbate in 1055 AD,[47] Grawat in 1086 AD,[47] Curewate (now Korbetha), Großkorbetha (Curuvadi and Curuuuati 881-899 AD) and Kleinkorbetha,[47] and Korbetha west of Leipzig;[48][49][5] In Moravia are Charwath,[50] or Charvaty near Olomouc, in Slovakia are Chorvaty and Chrovátice near Varadka.[48] The Charwatynia near Kashubians in district Wejherowo, and Сhаrwаtу or Klwaty near Radom in Poland among others.[30][50][44]

Thus in the Duchy of Carinthia one can find pagus Crouuati (954), Crauuati (961), Chrouuat (979) and Croudi (993) along upper Mura;[48][51] in Middle Ages the following place names have been recorded: Krobathen, Krottendorf, Krautkogel;[48] Kraut (before Chrowat and Croat) near Spittal.[48] In the Duchy of Styria there are toponyms such as Chraberstorf and Krawerspach near Murau, Chrawat near Laas in Judendorf, Chrowat, Kchrawathof and Krawabten near Leoben.[48][52] Along middle Mura Krawerseck, Krowot near Weiz, Krobothen near Stainz and Krobathen near Straganz.[48][53] In Slovenia there are also Hrovate, Hrovača, and Hrvatini.[48]

In the Southeastern Balkans, oeconyms Rvatska Stubica, Rvaši, Rvat(i) in Montenegro; several villages Hrvati and Gornji/Donji Hrvati in Bosnia and Herzegovina including Horvaćani (Hrvaćani Hristjanski) and Hrvatovići;[51] Rvatsko Selo, Hrvatska, and hamlet Hrvatske Mohve in Serbia;[54] North Macedonia has a place named Arvati (Арвати) situated near lower Prespa;[48] in Greece there is a Charváti or Kharbáti (Χαρβάτι) in Attica and Harvation or Kharbátion in Argolis, as well as Charváta (Χαρβάτα) on Crete;[48][49][44] and Hirvati in Albania,[48] among others in other countries.[54]

Anthroponyms

The ethnonym also inspired many anthroponyms which can be found in Eastern and Southeastern Europe. They are recorded at least since the 11th century in Croatia in the form of a personal name Hrvatin. Since the 14th century they can be found in the area of the Croatian capital city of Zagreb, in Bosnia and Herzegovina (especially in the area of East Herzegovina), as well as in the Dečani chrysobulls of Serbia, and since the 15th century in Montenegro, Kosovo, and North Macedonia.[54] In Poland the surnames Karwat, Carwad, Charwat, Carwath, Horwat, Horwath, Horwatowie are recorded since the 14th century in Kraków, Przemyśl and elsewhere, generally among the native Polish nobility, peasants, and local residents, but not among foreigners. They used it as a nickname, probably due to the influence of immigration from the Kingdom of Hungary.[55] Since the 16th century surname Harvat is recorded in Romania.[55]

It is mentioned in the form of the surnames Horvat, Horvatin, Hrvatin, Hrvatinić, Hrvatić, Hrvatović, Hrvet, Hervatić, H(e)rvatinčić, H(e)rvojević, Horvatinić, Horvačević, Horvatinović, Hrvović, Hrvoj, Rvat, and Rvatović.[51][54] Today Horvat is the most numerous surname in Croatia,[54] and the second most numerous in Slovenia (where the forms Hrovat, Hrovatin, and Hrvatin also exist), while Horváth is the most numerous surname in Slovakia and one of the most numerous in Hungary. In the Czech Republic, variation Charvat is found.

The male personal names Hrvoje, Hrvoj, Hrvoja, Horvoja, Hrvojhna, Hrvatin, Hrvajin, Hrvo, Hrvojin, Hrvojica, Hrvonja, Hrvat, Hrvad, Hrvadin, Hrviša, Hrvoslav, and Rvoje are derived from the ethnonym, as are the female names Hrvatica, Hrvojka, Hrvatina, and Hrvoja. Today the given name Hrvoje is one of the most common in Croatia.[54]

Synonyms

Throught history were used several synonyms for the Croats, their country and language, see the list below. In other cases, the Croatian ethnonym was also used in the sense of the "Illyrian costume" meant "pohârvātjen" in lexicon by Joakim Stulić (1810),[56] and the "Hungarian or Croatian costume" (alla croata),[57] the Cavalleria Croata in the Venetian Dalmatia,[58] the lingua croatica for the Glagolitic script (so-called St. Jerome's script) and in general for the Illyrian language (and foundation of the San Girolamo dei Croati and related Pontifical Croatian College of St. Jerome in Rome).[59][60]

- Croat(s) (Harvat, Horvat, Hervat, Croata and other variations)

- Dalmatinci (Dalmatians) - lexicon by Faust Vrančić (1595, 1605),[61] lexicon by Albert Szenczi Molnár (1604) the "Horvat" means "Croata, Dalmata, Illyricus",[62] lexicon by Andrija Jambrešić (1742).[63]

- Slovinci, Slovinjani (Slavs) - at least since the time of Croatian duke Domagoj (Sclavorum duce, mid-9th century), lexicon by Joakim Stulić (1806).[64]

- Iliri (Illyrians) - lexicon by Albert Szenczi Molnár (1604), lexicon by Jakov Mikalja (1649),[65][56] lexicon by Ivan Belostenec (17th century, publ. 1740), lexicon by Andrija Jambrešić (1742),[66] lexicon by Joakim Stulić (1806, 1810).[64][56]

- Liburni (Liburnians) - lexicon by Joakim Stulić (1806).[67]

- Vlachs (ethnic, social class), Morlachs and Ćići - became umbrella exonyms used by Venetians, Austrians and Ottomans for a social class, immigrants, and hinterland population of South Slavs in Dalmatia, Lika and Istria neverthless of their actual ethnic origin and identity, including for Croats.[68][69][70][71] From it emerged sub-ethnic identity of Vlahi in Istria.[72]

- Uskoks and Hajduks - people who were usually active as irregular soldiers in Dalmatia, Senj and Slavonia.[70][73][74]

- Bunjevci - a sub-ethnic group of Croats in Dalmatia, Lika and Bačka.[75]

- Šokci - a sub-ethnic group of Croats in Slavonia, Srijem, Baranja and Bačka.[76] Bartol Kašić in 1613 recorded that they speak "lingua croata".[77]

- Predavci - sub-ethnic identity of Catholic Croats and Bosnians in the 17th century continental part of Croatia (Slavonian Military Frontier and Varaždin Generalate), probably coming from Ottoman Bosnia Eyalet, and the term meaning refugees who surrended to someone (verb "predati"). In 1635 they were mentioned as "Bosnenis Croatae ex Turicia sponti venientes qui vulgo Praedavcis vocaventur", 1640 as "Catholici quoque Bosnenses Praedavci", in 1641 "Bosnenses catholici vulgo Praedavczy", 1651 as "catholici Bosnenses siue Praedauty", and 1662 as "Praedavcy, hoc est hominis Catholici Sclavonicae aut Croatiae nationis".[78]

- Bošnjani - ethnic identity of the people of medieval Bosnia (Christian and Muslim), for whom in the late 16th century Ottoman historian Gelibolulu Mustafa Ali wrote to be a territorial term while the people living there belong to the "Croatian nation" and are "tribe of Croats".[79]

- Tótok - in lexicon by Albert Szenczi Molnár (1604) a "Tót" means "Sclavus, Dalmata, Illyricus", a "Totorszag" (Tótsag) is "Dalmatia, Sclavonia, Illyrica, Illyricum" and "Totorszagi" language is "Dalmaticus".[62][80]

- Raci - umbrella exonym used between 15th and 18th century by the Hungarians for South Slavs who immigrated to the Southern Pannonian Plain (in Hungary), besides mostly Serbian Orthodox population, included Catholics (Croats); in lexicon's of Molnar, Mikalja and Stulli the terms Rascians/Serbs and Rascia/Serbia were not recorded as narrow synonyms for Slavs/Dalmatians/Illyrians and Slavonia/Dalmatia/Illyria,[81][56] but in broader context sometimes were identified as well in foreign documents.

- Bezjaci, Bazgoni and Fućki - sub-ethnic identity in continental part of Croatia, and Istria, who speak Kajkavian dialect in Croatia, and Northern Chakavian and Buzet dialect in Istria.[71][82][83]

- Fućki - sub-ethnic identity in Istria.[71]

- Kraljevci - sub-ethnic identity in Istria.[71][84][85]

- Benečani - sub-ethnic identity in Istria.[71][86]

- Boduli - sub-ethnic identity for people of the island of Krk, also Northern and Central Adriatic islands in general, in comparison to the population on the mainland of Kvarner and Dalmatia.[87]

- Croatia (Horvat orsag, Hervatska, Hervatia, Croazia and other variations)

- S(c)lavonia - since the 12th century was a synonym of the Kingdom of Croatia and Dalmatia, hence the Hungarian title of the Duke of Slavonia, the Pope letters referring to Croatia as "Sclavonia" and so on.[88]

- Dalmatia - at least since the time of Croatian duke Borna (early 9th century), lexicon by Fausto Veranzio (1595, 1605).[61]

- Illyria (Illyricum) - lexicon by Albert Szenczi Molnár (1604),[62] lexicon by Jakov Mikalja (1649).[65][56]

- Liburnia - at least since the time of Croatian duke Borna (early 9th century), lexicon by Joakim Stulić (1806).[67]

- Banadego - a 16th century Venetian term for the Northern Dalmatian hinterland which once was part of the Kingdom of Croatia and governed by Ban of Croatia, but then part of Ottoman Dalmatia (Croatian vilayet which became part of the Sanjak of Klis).[89]

- Croatian language (harvatski/harva(s)cki, horvatski, hrovatski, hervatski/hervaski and other variations)

- Dalmatinski (Dalmatian) - lexicon by Fausto Veranzio (1595, 1605);[61][90] lexicon by Jakov Mikalja (1649) the "Dalmaticus" with "Illyricus" and "Slovinski" is synonym for the same language,[91] which itself would correspond with the Croatian name.[56]

- Slovinski (Slavic) - poet Mavro Vetranović (1530s),[92] lexicons by Pavao Ritter Vitezović (1700) and Ivan Tanzlingher Zanotti (1704) and Ardelio della Bella (1728), statement that there's "one language although in three names [ilirički, slovinjski, arvacki]" by Filip Grabovac (1747),[93] lexicon by Joakim Stulić (1801, 1810).[56]

- Ilirski (Illyrian) - by Teofil Kristek and Alfonso Carrillo in the late 16th century,[94] grammar text by Lovro Šitović (1713),[92] lexicons by Pavao Ritter Vitezović (1700) and Ivan Tanzlingher Zanotti (1704) and Ardelio della Bella (1728), lexicon by Andrija Jambrešić (1742),[66] work Cvit razgovora naroda i jezika iliričkoga aliti arvackoga (1747) by Filip Grabovac,[93] in the mid-18th century Venetian bilingual declarations the "Illirico" was usually translated as "H(a)rvatski" (less "Slovinski" and "Ilirički"),[95] lexicon by Joakim Stulić (1801, 1810).[56]

- Bosanski (Bosnian) - Primož Trubar (1557) stated that the Croatian language is spoken in all of Croatia and Dalmatia, and by many Muslims (Turks) in Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well court in Istanbul, and perceived dalmatinski and bosanski as idioms of a language spoken by Croats.[96]

Official name of Croatia

Throughout its history, there were many official political names of Croatia in the 20th century. When Croatia was part of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, the entity was known as Banovina Hrvatska (Banovina of Croatia). After Yugoslavia was invaded in 1941, it became known as Nezavisna Država Hrvatska (Independent State of Croatia) as a puppet state of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. The present Croatian state became known as Federalna Država Hrvatska (Federal State of Croatia) when the country became part of the second Yugoslav state in 1944 following the third session of ZAVNOH. From 1945, the state became Narodna Republika Hrvatska (People's Republic of Croatia) and renamed again to Socijalistička Republika Hrvatska (Socialist Republic of Croatia) in 1963. After the constitution was adopted in December 1990, it was renamed to Republika Hrvatska (Republic of Croatia) and the name was retained when Croatia declared independence on June 25, 1991.

See also

References

Notes

- ^ "Kulturna kronika: Dvanaest hrvatskih stoljeća". Vijenac (in Croatian) (291). Zagreb: Matica hrvatska. 28 April 2005. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- ^ Mužić 2007, pp. 195–198.

- ^ Antić, Sandra-Viktorija (November 22, 2002). "Fascinantno pitanje europske povijesti" [Fascinating question of European history]. Vjesnik (in Croatian).

- ^ a b Gluhak 1989, p. 131.

- ^ a b c d Gluhak 1989, p. 130.

- ^ Gluhak 1993.

- ^ Matasović 2019, pp. 82, 85, 87, 94.

- ^ a b Budak 2018, pp. 98.

- ^ a b Gluhak 1989, p. 129f..

- ^ a b c d Rončević, Dunja Brozović (1993). "Na marginama novijih studija o etimologiji imena Hrvat" [On some recent studies about the etymology of the name Hrvat]. Folia onomastica Croatica (in Croatian) (2): 7–23. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ Gluhak 1989, p. 130–134.

- ^ Gluhak 1993, p. 270.

- ^ a b c Matasović 2008, p. 44.

- ^ Matasović 2019, pp. 81.

- ^ a b Matasović 2019, pp. 89.

- ^ Gołąb 1992, p. 325.

- ^ Gluhak 1989, p. 129.

- ^ Gołąb 1992, p. 326–328.

- ^ Howorth, H. H. (1882). "The Spread of the Slaves - Part IV: The Bulgarians". The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 11: 224. doi:10.2307/2841751. JSTOR 2841751.

It was a frequent custom With the Hunnic hordes to take their names from some noted leader, and it is therefore exceedingly probable that on their great outbreak the followers of Kubrat should have called themselves Kubrati, that is, Croats.I have argued in a previous paper of this series that the Croats or Khrobati of Croatia were so called from a leader named Kubrat or Khrubat. I would add here an addition to what I have there said, viz., that the native name of the Croats, given variously as Hr-wati, Horwati, cannot surely be a derivative of Khrebet, a mountain chain, as often urged, but is clearly the same as the well known man's name Horvath, familiar to the readers of Hungarian history and no doubt the equivalent of the Khrubat or Kubrat of the Byzantine writers, which name is given by them not only to the stem father of the Bulgarian kings, but to one of the five brothers Who led the Croat migration

- ^ Bury, J. B. (1889). A History of the later Roman empire from Arcadius to Irene (395-800). Vol. II. p. 275.

- ^ Madgearu, Alexandru; Gordon, Martin (2008). The Wars of the Balkan Peninsula: Their Medieval Origins. Scarecrow Press. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-8108-5846-6.

Henri Gregoire has tried to identify this Chrovatos with Kuvrat, the ruler of the Protobulgarians who rebelled against the Avars, recorded by other sources in the first third of the seventh century. As a matter of fact, now it is certain that Kuvrat lived in the North-Pontic steppes, not in Pannonia. He was the father of Asparuch, the ruler of the Protobulgarian group that immigrated to Moesia. Chrovatos was an invented eponym hero, like other such mythical ancestors of the European peoples.

- ^ Sakač, Stjepan K. (1937), "O kavkasko-iranskom podrijetlu Hrvata" [About Caucasus-Iranian origin of Croats], Renewed Life (in Croatian), 18 (1), Zagreb: Filozofski institut Družbe Isusove

- ^ "The same region appears in the Avestan Vidēvdāt (1.12) under the indigenous dialect form Haraxvaitī- (whose -axva- is typical non-Avestan)."Schmitt, Rüdiger (1987), "Arachosia", Encyclopædia Iranica, vol. 2, New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul, pp. 246–247

- ^ a b Katičić 1999, p. 12.

- ^ a b Marčinko 2000, p. 184.

- ^ Овчинніков О. Східні (2000). хорвати на карті Європи (in Ukrainian) // Археологічні студії /Ін-тут археології НАНУ, Буков. центр археол. досл. при ЧДУ. – Вип. 1. – Київ; Чернівці: Прут, p. 159

- ^ a b Gluhak 1989, p. 131f..

- ^ Gluhak 1989, p. 129–138.

- ^ Vasmer, Max. "хорват". Gufo.me. Этимологический словарь Макса Фасмера.

мн. -ы, др.-русск. хървати – название вост.-слав. племени близ Перемышля (Пов. врем. лет; см. Ягич, AfslPh 11, 307; Барсов, Очерки 70), греч. местн. нн. Χαρβάτι – в Аттике, Арголиде (Фасмер, Slaven in Griechen. 319), сербохорв. хр̀ва̑т, ср.-греч. Χρωβατία "Хорватия" (Конст. Багр., Dе adm. imp. 30), словен. раgus Crouuati, в Каринтии (Х в.; см. Кронес у Облака, AfslPh 12, 583; Нидерле, Slov. Star. I, 2, 388 и сл.), др.-чеш. Charvaty – название области в Чехии (Хроника Далимила), серболуж. племенное название Chruvati у Корбеты (Миккола, Ursl. Gr. I, 8), кашуб. местн. н. Charwatynia, также нариц. charwatynia "старая, заброшенная постройка" (Сляский, РF 17, 187), др.-польск. местн. н. Сhаrwаtу, совр. Klwaty в [бывш.] Радомск. у. (Розвадовский, RS I, 252). Древнее слав. племенное название *хъrvаtъ, по-видимому, заимств. из др.-ир. *(fšu-)haurvatā- "страж скота", авест. pasu-haurva-: haurvaiti "стережет", греч. собств. Χορόαθος – надпись в Танаисе (Латышев, Inscr. 2, No 430, 445; Погодин, РФВ 46, 3; Соболевский, РФВ 64, 172; Мейе–Вайан 508), ср. Фасмер, DLZ., 1921, 508 и сл.; Iranier 56; Фольц, Ostd. Volksboden 126 и сл. Ср. также Конст. Багр., Dе adm. imp. 31, 6–8: Χρώβατοι ... οἱ πολλην χώραν κατέχοντες. Менее убедительно сближение с лит. šarvúotas "одетый в латы", šárvas "латы" (Гайтлер, LF 3, 88; Потебня, РФВ I, 91; Брюкнер 176; KZ 51, 237) или этимология от ир. hu- "хороший" и ravah- "простор, свобода" (Соболевский, ИОРЯС 26, 9). Неприемлемо сближение с Καρπάτης ὄρος "Карпаты" (Птолем.), вопреки Первольфу (AfslPh 7, 625), Брауну (Разыскания 173 и сл.), Погодину (ИОРЯС 4,1509 и сл.), Маркварту (Streifzüge XXXVIII), Шрадеру – Нерингу (2, 417); см. Брюкнер, AfslPh 22, 245 и сл.; Соболевский, РФВ 64, 172; Миккола, AfslPh 42, 87. Неубедительна этимология из герм. *hruvаt-"рогатый": др.-исл. hrútr "баран" (Мух, РВВ 20,13).

- ^ a b c Lehr-Spławiński, Tadeusz (1951). "Zagadnienie Chorwatów nadwiślańskich" [The problem of Vistula Croats]. Pamiętnik Słowiański (in Polish). 2: 17–32.

- ^ Łowmiański, Henryk (2004) [1964]. Nosić, Milan (ed.). Hrvatska pradomovina (Chorwacja Nadwiślańska in Początki Polski) [Croatian ancient homeland] (in Croatian). Translated by Kryżan-Stanojević, Barbara. Maveda. pp. 24–43. OCLC 831099194.

- ^ Browning, Timothy Douglas (1989). The Diachrony of Proto-Indo-European Syllabic Liquids in Slavic. University of Wisconsin--Madison. p. 293.

- ^ Gołąb 1992, p. 324–328.

- ^ Popowska-Taborska, Hanna (1993). "Ślady etnonimów słowiańskich z elementem obcym w nazewnictwie polskim". Acta Universitatis Lodziensis. Folia Linguistica (in Polish). 27: 225–230. doi:10.18778/0208-6077.27.29. hdl:11089/16320. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ^ Majorov 2012, pp. 86–100, 129.

- ^ Matasović 2019, pp. 86–97.

- ^ Gluhak 1990, p. 229.

- ^ a b Katičić 1999, p. 11.

- ^ Marčinko 2000, p. 193.

- ^ Matasović 2019, pp. 90–95.

- ^ Matasović 2019, pp. 89, 93.

- ^ Matasović 2019, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Matasović 2019, pp. 84–85.

- ^ a b c Matasović 2019, pp. 84.

- ^ Velagić, Zoran (1997), "Razvoj hrvatskog etnonima na sjevernohrvatskim prostorima ranog novovjekovlja" [Development of the Croatian ethnonym in the Northern-Croatian territories of the early modern period], Migration and Ethnic Themes (in Croatian), 3 (1–2), Bjelovar: 54

- ^ Goldstein 2003.

- ^ a b c d e Marčinko 2000, p. 183.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Gračanin 2006, p. 85.

- ^ a b Vasmer 1941.

- ^ a b Marčinko 2000, p. 182.

- ^ a b c Leopold, Auburger (2019). "Putovima hrvatskoga etnonima Hrvat. Mario Grčević. Ime "Hrvat" u etnogenezi južnih Slavena. Zagreb ‒ Dubrovnik: Hrvatski studiji Sveučilišta u Zagrebu ‒ Ogranak Matice hrvatske u Dubrovniku, 2019., 292 str". Filologija (in Croatian). 73. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ^ Marčinko 2000, p. 181.

- ^ Marčinko 2000, p. 181-182.

- ^ a b c d e f Vidović, Domagoj (2016). "Etnonim Hrvat u antroponimiji i toponimiji". Hrvatski Jezik (in Croatian). 3 (3). Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ^ a b Łowmiański, Henryk (2004) [1964]. Nosić, Milan (ed.). Hrvatska pradomovina (Chorwacja Nadwiślańska in Początki Polski) [Croatian ancient homeland] (in Croatian). Translated by Kryżan-Stanojević, Barbara. Maveda. pp. 105–107. OCLC 831099194.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Grčević 2019, p. 208.

- ^ Grčević 2019, p. 79–80.

- ^ Grčević 2019, p. 90.

- ^ Štefanić, Vjekoslav (1976). "Nazivi glagoljskog pisma". Slovo (in Croatian) (25–26). Zagreb: Old Church Slavonic Institute: 17–76.

- ^ Grčević 2019, p. 168–174.

- ^ a b c Vrančić 1595, p. 138.

- ^ a b c Molnár 1604.

- ^ Jambrešić 1742, p. 171.

- ^ a b Stulić 1806a, p. 504.

- ^ a b Mikalja 1649, p. 129.

- ^ a b Jambrešić 1742, p. 382.

- ^ a b Stulić 1806a, p. 209.

- ^ Croatian Encyclopaedia (2011), Vlasi, LZMK

- ^ Croatian Encyclopaedia (2011), Morlaci, LZMK

- ^ a b Kursar, Vjeran (2013). "Being an Ottoman Vlach: On Vlach Identity(ies), Role and Status in Western Parts of the Ottoman Balkans (15th-18th Centuries)" (PDF). OTAM. 34. Ankara: 115–161.

- ^ a b c d e Blagonić, Sandi (2013). Od Vlaha do Hrvata. Austrijsko-mletačka politička dihotomija i etnodiferencijski procesi u Istri (in Croatian). Zagreb: Naklada Jesenski i Turk. p. 17–19, 67–79. ISBN 9789532224344.

- ^ S. Blagonić (2005). "Vlahi". Istrian Encyclopedia. LZMK.

- ^ Croatian Encyclopaedia (2013), Uskoci, LZMK

- ^ Croatian Encyclopaedia (2013), Hajduci, LZMK

- ^ Croatian Encyclopaedia (2011), Bunjevci, LZMK

- ^ Croatian Encyclopaedia (2011), Šokci, LZMK

- ^ Bara, Mario (2022). "Etnonim Šokac: imenovanje, ishodište i rasprostiranje" [Ethnonym Šokac: naming, origin and distribution]. Šokačka rič 19: Slavonski dijalekt i sociolingvistika (in Croatian). Vinkovci: Zajednica kulturno-umjetničkih djelatnosti Vukovarsko-srijemske županije. p. 335. ISBN 978-953-8366-02-4. Retrieved 18 January 2025.

- ^ Petrić, Hrvoje (2014). "Predavci - prilog poznavanju podrijetla stanovništva u Varaždinskom generalatu". Cris (in Croatian). XVI (1): 43–55.

- ^ Grčević 2019, p. 81.

- ^ Vidmarović, Đuro (2010). "Zvonimir Bartolić i Hrvati u susjednim zemljama s posebnim osvrtom na pomurske Hrvate u Mađarskoj". Kaj (in Croatian). 43 (1–2): 63–64.

- ^ Stulić 1806b, p. 303.

- ^ Croatian Encyclopaedia (2011), Bezjaci, LZMK

- ^ S. Blagonić (2005). "Fućki". Istrian Encyclopedia. LZMK.

- ^ S. Blagonić (2005). "Kraljevci". Istrian Encyclopedia. LZMK.

- ^ S. Blagonić (2005). "Bazgoni". Istrian Encyclopedia. LZMK.

- ^ S. Blagonić (2005). "Benečani". Istrian Encyclopedia. LZMK.

- ^ Croatian Encyclopaedia (2011), Boduli, LZMK

- ^ Grčević 2019, p. 169.

- ^ Ivetic, Egidio (2022). Povijest Jadrana: More i njegove civilizacije [History of the Adriatic: A Sea and Its Civilization] (in Croatian). Srednja Europa, Polity Press. p. 143. ISBN 9789538281747.

- ^ Grčević 2019, p. 172–173.

- ^ Mikalja 1649, p. 624.

- ^ a b Grčević 2019, p. 206.

- ^ a b Grčević 2019, p. 209.

- ^ Grčević 2019, p. 171.

- ^ Šimunković 1996, p. 12.

- ^ Grčević 2019, p. 167.

Primary sources

- Vrančić, Faust (1595), Dictionarium quinque nobilissimarum Europæ linguarum, Latinæ, Italicæ, Germanicæ, Dalmatiæ, & Vulgaricæ (in Latin), Novi Liber

- Molnár, Albert Szenczi (1604), Dictionarium Latinovngaricvm and Dictionarivm Vngarico-Latinvm (in Latin), Hutter

- Mikalja, Jakov (1649), Blago Jeziga Slovinskoga ... Thesaurus linguæ Illyricæ; sive, Dictionarium, Illyricum in quo verba Illyrica Italice et Latine redduntur (in Latin)

- Jambrešić, Andrija (1742), Lexicon Latinum interpretatione Illyrica, Germanica, et Hungarica locuples: in usum potissimum studiosae juventutis digestum (in Latin)

- Stulić, Joakim (1806a), Rjecsosloxje slovinsko-italiansko-latinsko u komu donosuse upotrebljenia, urednia, mucsnia istieh jezika krasnoslovja nacsini, izgovaranja i prorjecsja A-O (in Latin), Martekini

- Stulić, Joakim (1806b), Rjecsosloxje slovinsko-italiansko-latinsko u komu donosuse upotrebljenia, urednia, mucsnia istieh jezika krasnoslovja nacsini, izgovaranja i prorjecsja P-Z (in Latin), Martekini

Secondary sources

- Budak, Neven (2018), Hrvatska povijest od 550. do 1100. [Croatian history from 550 until 1100] (in Croatian), Leykam international, pp. 86–118, ISBN 978-953-340-061-7, archived from the original on 2022-10-03, retrieved 2018-06-03

- Gluhak, Alemko (1989), "Podrijetlo imena Hrvat" [Origin of the name Croat], Jezik: Časopis Za Kulturu Hrvatskoga Književnog Jezika (in Croatian), 37 (5), Zagreb: Jezik (Croatian Philological Society): 129–138

- Gluhak, Alemko (1990), Porijeklo imena Hrvat [Origin of the name Croat] (in Croatian), Zagreb, Čakovec: Alemko Gluhak

- Gluhak, Alemko (1993), Hrvatski etimološki rječnik [Croatian etymological dictionary] (in Croatian), Zagreb: August Cesarec, ISBN 953-162-000-8

- Gołąb, Zbigniew (1992), The Origins of the Slavs: A Linguist's View, Columbus: Slavica, ISBN 9780893572310

- Goldstein, Ivo (2003), Hrvatska povijest [Croatian history] (in Croatian), Zagreb: Novi Liber, ISBN 953-6045-22-2

- Gračanin, Hrvoje (2006), Kratka povijest Hrvatske za mlade I. - od starog vijeka do kraja 18. stoljeća [Short history of Croatia for youth I. - from the old age till the end of 18th century] (in Croatian), Zagreb: Sysprint, ISBN 953-232-111-X

- Grčević, Mario (2019), Ime "Hrvat" u etnogenezi južnih Slavena [The name "Croat" in the ethnogenesis of the southern Slavs], Zagreb, Dubrovnik: Hrvatski studiji Sveučilišta u Zagrebu – Ogranak Matice hrvatske u Dubrovniku, ISBN 978-953-7823-86-3

- Katičić, Radoslav (1999), Na kroatističkim raskrižjima [At Croatist intersections] (in Croatian), Zagreb: Hrvatski studiji, ISBN 953-6682-06-0

- Majorov, Aleksandr Vjačeslavovič (2012), Velika Hrvatska: etnogeneza i rana povijest Slavena prikarpatskoga područja [Great Croatia: ethnogenesis and early history of Slavs in the Carpathian area] (in Croatian), Zagreb, Samobor: Brethren of the Croatian Dragon, Meridijani, ISBN 978-953-6928-26-2

- Marčinko, Mato (2000), "Tragovi i podrijetlo imena Hrvat" [Traces and the origin of Croatian name], Indoiransko podrijetlo Hrvata [Indo-Iranian origin of Croats] (in Croatian), Naklada Jurčić, ISBN 953-6462-33-8

- Matasović, Ranko (2008), Poredbenopovijesna gramatika hrvatskoga jezika [A Comparative and Historical Grammar of Croatian] (in Croatian), Zagreb: Matica hrvatska, ISBN 978-953-150-840-7

- Matasović, Ranko (2019), "Ime Hrvata" [The Name of Croats], Jezik (Croatian Philological Society) (in Croatian), 66 (3), Zagreb: 81–97

- Šimunković, Ljerka (1996), Mletački dvojezični proglasi u Dalmaciji u 18. stoljeću (in Croatian), Split: Književni Krug, ISBN 9789531630412

- Vasmer, Max (1941), Die Slaven in Griechenland [The Slavs in Greece] (in German), Berlin: Verlag der Akademie der Wissenschaften