Odissi music

| Oṛiśī Sangīta |

| Odissi music |

|---|

|

| Composers |

| Shāstras |

| Compositions |

| Instruments |

| Indian classical music |

|---|

|

| Concepts |

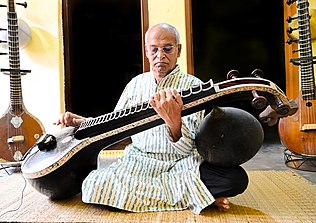

Odissi music (Odia: ଓଡ଼ିଶୀ ସଙ୍ଗୀତ, romanized: oṛiśī sangīta, Odia: [oɽisi sɔŋgit̪ɔ] ⓘ) is a genre of classical music originating from the eastern state of Odisha. It is played on traditional instruments like the mardala, veena, and bansuri. Rooted in the ancient ritual music tradition dedicated to Lord Jagannatha, Odissi music has a rich history spanning over two thousand years, distinguished by its unique sangita-shastras (musical treatises), a specialized system of Ragas and Talas, and a distinctive style of performance. While some Indian classical music like Carnatic music and Hindustani music, traditions evolved separately over centuries, Odissi music has retained its classical purity and its characteristic devotion-centered compositions. Odissi compositions are largely written in Sanskrit and Odia.[1][2][3]

The various aspects of Odissi music include Odissi prabandha, Chaupadi, Chhanda, Champu, chautisā, janāna, Mālasri, Bhajana, Sarimāna, Jhulā, Kuduka, Koili, Poi, Boli, and more. Presentation dynamics are roughly classified into four: raganga, bhabanga, natyanga and dhrubapadanga. Some great composer-poets of the Odissi tradition are the 12th-century poet Jayadeva, Balarama Dasa, Atibadi Jagannatha Dasa, Dinakrusna Dasa, Kabi Samrata Upendra Bhanja, Banamali Dasa, Kabisurjya Baladeba Ratha, Abhimanyu Samanta Singhara and Kabikalahansa Gopalakrusna Pattanayaka.[4]

According to Bharata Muni's Natya Shastra, Indian classical music has four significant branches: Avanti, Panchali, Odramagadhi and Dakshinatya. Of these, Odramagadhi exists in the form of Odissi music. Odissi music crystallised as an independent style during the time of the early medieval Odia poet Jayadeva, who composed lyrics meant to be sung, set to ragas and talas unique to the local tradition.[5] However, Odissi songs were written even before the Odia language developed. Odissi music has a rich legacy dating back to the 2nd century BCE, when king Kharavela, the ruler of Odisha (Kalinga), patronized this music and dance.[6]

The traditional artforms of Odisha such as Mahari, Gotipua, Prahallada Nataka, Radha Prema Lila, Pala, Dasakathia, Bharata Lila, Khanjani Bhajana, etc. are all based on Odissi music. Odissi is one of the classical dances of India from the state of Odisha; it is performed with Odissi music.[7]

History

Ritual music of Jagannatha Temple

Odissi music is intimately and inextricably associated with the Jagannatha temple of Puri. The deity of Jagannatha is at the heart of Odisha's culture, and Odissi music was originally the music offered as a sevā or service to Jagannatha. Every night during the Badasinghara or the last ritual of the deity, the Gitagovinda of Jayadeva is sung, set to traditional Odissi ragas & talas. This tradition has continued unbroken since the time of Jayadeva, who himself used to sing in the temple. After the time of the poet, the singing of the Gitagovinda according to the authentic Odissi ragas & talas was instated as a mandatory sevā at the temple, to be performed by the Maharis or Devadasis, systematically recorded in inscriptions, the Mādalā Pānji and other official documents that describe the functioning of the temple. To this date, the Jagannatha temple remains the fountainhead of Odissi music and the most ancient & authentic compositions (including a few archaic Odia chhandas and jananas by Jayadeva himself) survive in the temple tradition, although the Devadasis are no more found owing to their systematic eradication by the British government.

Prehistoric music

Ancient Odisha had a rich culture of music, which is substantiated by many archaeological excavation throughout the state of Odisha. At Sankarjang in the Angul district, the initial spade work exposed the cultural stratum of the Chalcolithic period (400 BC onward). From here, polished stone celts and hand-made pottery have been excavated. Some of the Celts are narrow but large in size. Thus they are described as Bar-celts. On the basis of bar-celts discovered in Sankarjung it could be argued that they were an earlier musical instrument in India. Scholars have referred to these as the earliest discovered musical instruments of South East Asia.[8]

Kharabela & Ancient Caves

There are vivid sculptures of musical instruments, singing and dancing postures of damsels in the Ranigumpha Caves in Khandagiri and Udayagiri at Bhubaneswar. These caves were built during the reign of the Jain ruler Kharabela of Kalinga in the 2nd century BC.[1] In inscriptions, Kharabela has been described as an expert in classical music (gandhaba-beda budho) and a great patron of music (nata-gita-badita sandasanahi).[9] Madanlal Vyas describes him as an expert who had organized a music programme where sixty four instruments were played in tandem. Kharabela was an emperor of the Chedi dynasty. Chedi was the son of Kousika, a Raga that is said to have been created by sage Kasyapa according to Naradiya Sikhya. The ancient musicologists of Odisha, like Harichandana belonged to the Naradiya school. The Raga Kousika is an extremely popular raga in the Odissi tradition, even until date.[1]

One of the caves of Udayagiri is known as the Bajaghara Gumpha, literally meaning 'hall of musical instruments'. It is designed such that any musical recital inside is amplified by the acoustics of the cave.[9]

Sculpture

In the temples of Odisha, oldest among them dating to the 6th century AD, such as Parasuramesvara, Muktesvara, Lingaraja and Konarka, there are hundreds of sculptures depicting musical performances and dancing postures.

Natya Shastra of Bharata Muni

Bharata's Natya Shastra is the most respected ancient treatise on Indian music & dance. Bharata in his seminal work has mentioned four different 'pravrittis' of natya (which includes both music & dance). The classification into pravrittis can be roughly said to be a stylistic classification, based on unique features of the regional styles that were distinctive enough in Bharata's time. The four pravrittis mentioned are Avanti, Dakshinatya, Panchali and Odramagadhi (or Udramagadhi). Odra is an ancient name of Odisha. Parts of ancient Kalinga, Kangoda, Dakhina Kosala, Tosali, Matsya Desa, Udra now constitute the state of Odisha. The classical music that prevailed in these regions was known as Udramagadhi. The post-Jayadeva text Sangita Ratnakara also makes a reference to the same. In the present times, it is this very system that goes under the rubric Odissi music.[1][9]

Tradition

Charyapada and Buddhist Music

For a long period Buddhism was the major religion of Odisha. The Vajrayana and Sahajayana branches of Buddhism were particularly influential, and scholars opine that Odisha or Oddiyana was the birth place of Vajrayana itself. Between the seventh and eleventh centuries, the Charya Gitika of Buddhist Mahasiddhas or Siddhacharyas were written and composed. Many of the Mahasiddhas were born in Odisha and wrote in a language that is extremely close to present-day Odia. Some of these songs were ritually sung on the ratha of Jagannatha during the Ratha Jatra.[1]

The Charyapadas or Charya songs usually consist of five or six padas. The last pada bears the name of the poet. The ragas to sing them have been indicated by the authors themselves, but no mention of tala is found. The ragas used by the Mahasiddhas continued to be popular in Odissi music for centuries afterwards, and remain important to this day. Many of the raga names as written bear significant resemblance with the raga nomenclature of Odisha & the pronunciations of raga names in the Odissi tradition, such as the mention of Baradi and not Varali. Some of the ragas mentioned in the Charyapadas are :

| Raga name as mentioned in the Charyapadas | Present-day raga name in Odissi music |

|---|---|

| Aru | |

| Bangāla | Bangāla |

| Barādī | Barādī |

| Bhairabī | Bhairabī |

| Debakrī | Debakirī |

| Deśākha | Deśākhya |

| Dhanāśrī | Dhanāśrī |

| Gabadā | Gaudā |

| Gunjarī | Gujjarī |

| Kāhnu Gunjarī | |

| Kāmoda | Kāmoda |

| Mallārī | |

| Mālasī | Mālaśrī |

| Mālasī Gabudā | Mālaśrī Gaudā |

| Rāmakrī | Rāmakerī |

| Śābarī | Śābarī |

Jayadeva and Gita Govinda

The Gitagovinda written by 12th-century poet Jayadeva is known to be one of the earliest, if not the earliest Indian song where the author has indicated with precision the exact raga and tala (mode of singing and the rhythm) of each song. This makes it one of the earliest texts of Indian classical music. Many of the ragas indicated in the Gitagovinda continue to be highly popular in Odissi music even now, and some of the talas mentioned in it are exclusive to the tradition of Odissi music.[9]

These indications have been compiled below according to the ashtapadi number, based on the important ancient copies of the Gita Govinda and its commentaries such as Sarvangasundari Tika of Narayana Dasa (14th century), Dharanidhara's Tika (16th century), Jagannatha Mishra's Tika (16th century), Rasikapriya of Rana Kumbha (16th century) and Arthagobinda of Bajuri Dasa (17th century).[10]

- Mālava, Mālavagauḍa or Mālavagauḍā

- Maṅgala Gujjarī or Gurjarī

- Basanta

- Rāmakirī or Rāmakerī

- Gujjarī or Gurjarī

- Guṇḍakirī or Guṇḍakerī or Mālavagauḍa

- Gujjarī or Gurjarī

- Karṇṇāṭa

- Deśākhya or Deśākṣa

- Deśī Barāḍi or Deśa Barāḍi or Pañchama Barāḍi

- Gujjarī or Gurjarī

- Guṇḍakirī or Guṇḍakerī

- Mālava or Mālavagauḍā

- Basanta

- Gujjarī or Gurjarī

- Barāḍi or Deśa Barāḍi or Deśī Barāḍi

- Bhairabī

- Gujjarī or Gurjarī or Rāmakerī

- Deśī or Deśa Barāḍi

- Basanta

- Barāḍi or Deśa Barāḍi

- Barāḍi

- Rāmakirī or Rāmakerī or Bibhāsa

- Rāmakirī or Rāmakerī

Most of the ragas and talas indicated by Jayadeva, with the exception of one or two, continue to be in practice in the tradition of Odissi music.[10]

The poet Jayadeva is known to have started the Mahari or Devadasi tradition at the Jagannatha temple of Puri, where every night the Gitagovinda is ritually sung & enacted in front of Jagannatha, continuing to this day. In the Jayabijaya Dwara inscription of Prataparudra Deba, the singing of Gitagovinda and adherence to the traditional Odissi ragas indicated by the poet has been referred to as mandatory. The Maharis were also banned from learning any other songs except the Gitagovinda ; this was considered an 'act of defiance towards Jagannatha'.[9]

Pt. Raghunath Panigrahi is known for his contributions in popularising the Gitagovinda through Odissi music & Odissi dance across the globe. Scholar-musicians such as Guru Gopal Chandra Panda have also attempted to reconstruct melodies of the ashtapadis of the Gita Govinda in adherence to the poet's original indications, and based on extant traditional rhythmic & melodic patterns in Odissi music.[10]

Gopala Nayaka

During the reign of Alauddin Khilji, Gopala Nayaka had an important role of popularising old Indian music. Some scholars from Odisha in the first part of the 20th century have written about local legend that states Gopala Nayaka was from Odisha.[11]

After the reign of Mukunda Deba in the 16th century, Odissi music suffered during the Maratha rule in Odisha during the 17th and 18th century AD.

British rule

During the 18th and 19th centuries, Odissi music was chiefly patronised by local kings of princely states of Odisha. This included the Gajapati of Puri as well as the rulers of the kingdoms of Paralakhemundi, Mayurbhanj, Ghumusara, Athagada, Athagada Patana, Digapahandi (Badakhemundi), Khallikote, Sanakhemundi, Chikiti, Surangi, Jeypore, Ali, Kanika, Dhenkanal, Banapur, Sonepur, Baramba, Nilgiri, Nayagarh, Tigiria, Baudh, Daspalla, Bamanda (Bamra), Narasinghapur, Athamallik as well as places with a significant Odia population and cultural history such as Tarala (Tharlakota), Jalantara (Jalantrakota), Manjusa (Mandasa), Tikili (Tekkali) and Sadheikala (Seraikela). Rulers often patronised poet-composers and skilled musicians, vocalists and instrumentalists. Musicians were appointed in royal courts and honoured with land or other rewards. Many kings were themselves skilled musicians and poets, such as Gajapati Kapilendra Deba of Puri or Biswambhara Rajendradeba of Chikiti.

Treatises

| ||||||

| Music of India | ||||||

| Genres | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Traditional

Modern |

||||||

| Media and performance | ||||||

|

||||||

| Nationalistic and patriotic songs | ||||||

|

||||||

| Regional music | ||||||

|

||||||

Several dozens of treatises on music written in Odisha have been found. It is known that at least from the 14th century onwards, there was a continuous tradition of musicology in the state. Many of the texts have been critically edited and published by the Odisha Sangeet Natak Akademi and the Department of Culture, Odisha. Of these, the core texts of Odissi music are:[1][12][13]

- Gita Govinda of Jayadeva (12th century)

- Sangita Sara of Hari Nayaka (14th century)

- Gita Prakasa of Krusnadasa Badajena Mahapatra (15th century)

- Sangita Narayana of Gajapati Narayanadeba, king of Paralakhemundi - written by Kaviratna Purusottama Misra (17th century)

- Sangitarnava Chandrika of Nilakantha of Kalakala

- Sangita Muktabali of Harichandana, king of Kanika

- Natya Manorama of Raghunatha Ratha (also called Sangita Manorama)

- Sangita Sarani of Kaviratna Narayana Mishra of Paralakhemundi

- Sangita Kamoda of Kavibhusana Gopinatha Patra of Paralakhemundi

- Kalankura Nibandha of Kalankura Muni

- Sangita Sadananda of Sadananda Kabisurjya Brahma

- Sangitasara Boli of Bandhu Binakara

- Gitaprakasa Boli of Giri Gadadhara Dasa

- Lakhyana Chandrodaya of Kabichandra Raghunatha Parichha of Paralakhemundi

- Sangita Kamada

- Sangita Kaumudi of unknown authorship

- Sangita Nirnaya of Bira Narayana

- Sangita Chintamani of Kamalalochana Khadgaraya

Jayadeva, the 12th century Sanskrit saint-poet, the great composer and illustrious master of classical music, has immense contribution to Odissi music. During his time Odra-Magadhi style music got shaped and achieved its classical status. He indicated the classical ragas prevailing at that time in which these were to be sung. Prior to that there was the tradition of Chhanda. A number of treatises on music have been found,[14][15] the earliest of them dating back to 14th century.

The musicologists of Odisha refer to a variety of ancient texts on music such as Bharata Muni's Natyashastra, Vishnu Purana, Shiva Samhita, Brahma Samhita, Narada Samhita, Parasurama Samhita, Gita Govinda, Kohaliya, Hari Nayaka's Sangitasara, Matanga Tantra, Mammatacharya's Sangita Ratnamala, Kalankura Nibandha, Panchama Sara Samhita, Raga Viveka, Sangita Chandrika, Sangita Kaumudi, Sangita Siromani, Vanmayaviveka, Shivavivekaprabandha, Sangita Damodara and more. The aforesaid texts are thus known to have been in vogue in Odisha during the post-15th century period.[1]

Characteristics

Odissi Sangita comprises four shastric classifications i.e. Dhruvapada, Chitrapada, Chitrakala and Panchali, described in the above-mentioned texts. The Dhruvapada is the first line or lines to be sung repeatedly. Chitrapada means the arrangement of words in an alliterative style. The use of art in music is called Chitrakala. Kabisurjya Baladeba Ratha, the renowned Odia poet wrote lyrics, which are the best examples of Chitrakala. All of these were Chhanda (metrical section) contains the essence of Odissi music. The Chhandas were composed by combining Bhava (theme), Kala (time), and Swara (tune). The Chautisa represents the originality of Odissi style. All the thirty four (34) letters of the Odia alphabet from 'Ka' to 'Ksa' are used chronologically at the beginning of each line.

A special feature of Odissi music is the padi, which consists of words to be sung in Druta Tala (fast beat).[16] Odissi music can be sung to different talas: Navatala (nine beats), Dashatala (ten beats) or Egaratala (eleven beats). Odissi ragas are different from the ragas of Hindustani and Karnataki classical music.

The primary Odissi mela ragas are Kalyana, Nata, Sri, Gouri, Baradi, Panchama, Dhanasri, Karnata, Bhairabi and Sokabaradi.[17]

Some of the distinctive and authentic ragas of the Odissi music tradition are : Abhiri, Amara, Ananda, Anandabhairabi, Ananda Kamodi, Ananda Kedara, Arabhi, Asabari, Bangala, Baradi, Basanta, Bhairabi, Bichitra Desakhya, Bichitradesi, Bichitra Kamodi, Chakrakeli, Chalaghanta Kedara, Chhayatodi, Chintabhairaba, Chinta Kamodi, Debagandhari, Debakiri, Desa Baradi, Desakhya, Desapala, Dhanasri, Dhannasika, Gauda, Gaudi, Ghantaraba, Gundakeri, Kali, Kalyana, Kalyana Ahari, Kamoda, Kamodi, Kaphi, Karnata, Kausiki, Kedara, Kedaragauda, Kedara Kamodi, Karunasri, Khambabati, Khanda Bangalasri, Khandakamodi, Kolahala, Krusna Kedara, Kumbhakamodi, Kusuma Kedara, Lalita, Lalita Basanta, Lalita Kamodi, Lalita Kedara, Lilataranga, Madhumangala, Madhumanjari, Madhura Gujjari, Madhusri, Madhu Saranga, Madhyamadi, Malasri, Malasrigauda, Mangala, Mangala Dhanasri, Mangala Gujjari, Mangala Kamodi, Mangala Kausiki, Mangala Kedara, Mallara, Manini (Malini), Marua, Megha, Meghaparnni, Misramukhari, Mohana, Mohana Kedara, Mukhabari (Mukhari), Nagaballi, Nagadhwani, Nalinigauda, Nata, Nata Kedara, Natanarayana, Natasaranga, Panchama, Punnaga, Punnaga Baradi, Pahadia Kedara, Panchama Baradi, Paraja, Rajahansi Chokhi, Ranabije, Rasakamodi, Rasamandara, Rasamanjari, Sabari, Saberi, Sankarabharana, Sindhukamodi, Sokabaradi, Sokakamodi, Soma, Sri, Suddhadesi, Surata, Suratha Gujjari, Todi.[18][19][20]

Odissi music is sung through Raganga, Bhabanga and Natyanga, Dhrubapadanga followed by Champu, Chhanda, Chautisa, Pallabi, Bhajana, Janana, and Gita Govinda.

Odissi music has codified grammars, which are presented with specified Raagas. It has also a distinctive rendition style. It is lyrical in its movement with wave-like ornamentation (gati andolita). The pace of singing in Odissi is not very fast nor too slow (na druta na bilambita), and it maintains a proportional tempo (sama sangita) that is very soothing.

Though there has been cross-cultural influence between Hindustani music and Persian music, Odissi music has remained relatively unaffected.[1]

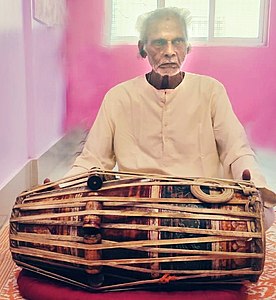

Mardala

The Mardala is a percussive instrument native to the state of Odisha. It is traditionally used as the primary percussive instrument with Odissi music.[2] The Mardala is different from other instruments that might have similar names in the Indian subcontinent due to its unique construction, acoustic features and traditional playing technique.[21]

Raghunatha Ratha, an ancient musicologist of Odisha extols the Mardala in his treatise, the Natya Manorama as:[22]

ānaddhe marddaḻaḥ śreṣṭho |

Among the membranophones, |

The Jagannatha temple of Puri has for centuries had a Mardala servitor. This was known as the 'Madeli Seba' and the percussionist was ritually initiated into the temple by the Gajapati ruler. The Mardala used to be the accompanying instrument to the Mahari dance, the ancestor of present-day Odissi dance, one of the major classical dance forms of India. In hundreds of Kalingan temples across the state of Odisha, including famous shrines such as Mukteswara and Konarka, the Mardala features prominently, usually in a niche of an alasakanya playing the instrument. There is a pose by the name mardalika replicating the same stance in Odissi dance.

The playing of the Mardala is based on the tala-paddhati or rhythmic system of Odissi music. A tala is a rhythmic structure in Indian music. The talas in use in Odissi music are distinctive, and are not found in other systems of Indian music. The regional terminology used in the Mardala's context are kalā, ansā, māna, aḍasā, bhaunri, bhaunri aḍasā, tāli, khāli, phānka, bāṇi, ukuṭa, pāṭa, chhanda, bhangi, etc.[16] The sabda-swara pata, a traditional component based on the Mardala's beats was integrated into Odissi dance by Guru Deba Prasad Das.[23] Though several hundred talas are defined in treatises, some are more common : ekatāli, khemaṭā or jhulā, rūpaka, tripaṭā, jhampā, āḍatāli, jati, āditala, maṭhā.[24] Other talas that are also used are nihsāri, kuḍuka, duāḍamāna, sarimāna, upāḍḍa, paḍitāla, pahapaṭa, aṭṭatāla, āṭhatāli and jagannātha. The talas have a characteristic swing that is typical of and universally found in Odissi music.

The Mardala is intimately associated with the Jagannatha temple and thus has a very esteemed position in the culture of Odisha. Many Gurus have worked for carrying forward the legacy of the instrument. Adiguru Singhari Shyamsundar Kar, Guru Banamali Maharana, Guru Kelucharan Mahapatra, Guru Padmanabha Panda, Guru Basudeba Khuntia, and Guru Mahadev Rout were among the great Gurus of Mardala in the 20th century.

Guru Rabinarayan Panda, Guru Janardana Dash, Guru Dhaneswar Swain, Guru Sachidananda Das, Guru Bijaya Kumar Barik, Guru Jagannath Kuanr are among modern-day exponents of the Mardala. Many veteran Gotipua masters have also excelled in the Mardala : Guru Birabara Sahu, Guru Lingaraj Barik, Guru Maguni Das and others.

As a solo instrument

The role of the Mardala as a solo instrument has been presented for the last few decades with great success, apart from its better-known role as an accompaniment in the ensemble for Odissi music and dance.[25] The solo performances follow a specific rule or pranali : starting with a jamana, then proceeding onto chhanda prakarana, ragada, etc.[26] Guru Dhaneswar Swain is known for his pioneering efforts to promote solo performances of the Mardala and bring other traditional percussion instruments of Odisha onto the concert stage.[27][28][29] Guru Dhaneswar Swain, the first solo Mardala player who had presented an extended solo performance on the Mardala under the guidance of Guru Banamali Maharana, was the very first of its kind.

Ensemble

The traditional ensemble accompanying an Odissi music recital is said to be 'binā benu mardala' : Bina or Veena, Benu or Flute and the Mardala. These form the three primary classes of instruments described in the shastras : tat or stringed, susira or wind and anaddha or percussive. All three instruments have been depicted in the stone temples & caves of Odisha built over the last two millennia. The three instruments were also officially appointed as sebāyatas in the Jagannatha Temple of Puri as described in the Madala Panji. Apart from these three instruments, some other traditional accompanying instruments are the gini, karatāla, khola or mrudanga, jodināgarā, mahurī or mukhabīnā, jalataranga etc. At least since the 18th century, other instruments such as the violin (behelā) and Sitar have also been employed.[9] The harmonium has become popular from the early twentieth century.

While the flute and Mardala continue to be popular, the Odissi Bina is no longer as widespread as it once used to be. Some of the exponents of the Odissi Bina were Sangitacharya Adwaita Guru and Gayaka Siromani Andha Apanna Panigrahi. The Odissi Bina (Veena) was preserved by Acharya Tarini Charan Patra in the twentieth century and is now kept alive by his disciple Guru Ramarao Patra.[30]

Relation with other classical music

At one time the Kalinga Empire extended all the way up to the river Kaveri and incorporated major parts of Karnataka. Gajapati Purusottama Deva of Odisha conquered Kanchi and married the princess. Some raagas specific to Odisha are "Desakhya", "Dhanasri", "Belabali", "Kamodi", "Baradi" etc. Additionally, some Odissi raagas bear the same names as Hindustani or Carnatic raagas, but have different note combinations. Furthermore, there are many raagas that have the same note combinations in Hindustani, Carnatic and Odissi styles, but are called by different names. Each stream, however, has its own distinct style of rendition and tonal development despite the superficial similarity in scale.

Odissi music in modern times

The great exponents[14][15] of Odissi music in modern times are Adiguru Singhari Shyamsundar Kar, Astabadhani Acharya Tarini Charan Patra, Banikantha Nimai Charan Harichandan, Gokul Srichandan, Nrusinghanath Khuntia, Lokanath Rath, Lokanath Pala, Mohan Sundar Deb Goswami, Markandeya Mahapatra, Kashinath Pujapanda, Kabichandra Kalicharan Pattnaik, Sangita Sudhakara Balakrushna Dash, Radhamani Mahapatra, Bisnupriya Samantasinghar, Bhubaneswari Mishra, Padmashree Shyamamani Devi, Dr. Gopal Chandra Panda, Padmakesari Dr. Damodar Hota, Padmashree Prafulla Kar, Padmashree Suramani Raghunath Panigrahi, Ramarao Patra (Bina/Veena),Sangita Gosain, Ramhari Das who have achieved eminence in classical music.[30]

Classicality

The renowned scholar and cultural commentator Jiwan Pani mentions four parameters that any system of music has to satisfy in order to be called 'classical' or shastric :

- The tradition must be over a century old.

- The system must be based on one or more written shastras or treatises.

- There must be a number of ragas at the core of the system.

- The ragas at the core of the system and other acquired ragas must be delineated in a distinctive style.

Jiwan Pani further goes on to illustrate in his works each of these aspects with respect to Odissi music. The tradition of Odissi music is nearly a millennium old, there are several ancient musical treatises produced in the state of Odisha for several centuries, there are unique ragas and a distinctive manner of rendition. Pani further argues :[31]

From the discussions above, it is evident that Odissi music is a distinctive shastric (classical) system. Again, it is now accepted that Odissi dance is undoubtedly a shastric style. Undoubtedly, music is the life breath of dance. Therefore, it will not be logical to say that the body, that is the Odissi dance, is shastric, but its life, that is, the music, is not shastric.

Other scholars such as Pandit Dr. Damodar Hota[32] and Professor Ramhari Das have raised concerns over the apathy of the government & resultant lack of patronage towards preservation and popularisation of classical music traditions other than the two major systems.[33] Dr. Hota also points to the distortion of Odissi Music as some dance musicians since the 1950s catered their music solely to the revived dance form using Hindustani and Carnatic music as reference points instead of cultivating knowledge and mastery of the distinctive classicism and performance aspects of Odissi Music. Odissi music was not as well known as Odissi dance to musicians & dancers outside Odisha, which led to an appropriation of musical integrity and composition of dance music without adhering to the Odissi tradition. Performing Odissi dance to non-Odissi music was heavily criticised by traditional Gurus of both Odissi dance & Odissi music; it was seen as a disruption of the Odia tradition in which Odia language & literature blended harmoniously with Odissi music & Odissi dance.

Most recently, in order to popularize the Odissi music the State Government's Culture Department has undertaken a massive programme named 'Odissi Sandhya' to be performed in all major cities of the country. The programme is being executed through Guru Kelu Charan Mohapatra Odissi Research Centre in association with different cultural organizations located in different parts of the country, like Central Sangeet Natak Academy, Eastern Zonal Cultural Centre, Kolkata, and Prachin Kalakendra, Chandigarh.

Exponents

- Sangitacharya Mahanta Sri Adwaita Guru

- Guru Gokula Chandra Srichandana

- Gayaka Siromani Apanna Panigrahi

- Natyacharya Kabichandra Kali Charan Patnaik

- Astabadhani Acharya Tarini Charan Patra

- Sangita Sudhakara Balakrushna Dash

- Suramani Raghunath Panigrahi

- Bhajana Samrata Bhikari Charan Bal

- Vidushi Shyamamani Devi

- Guru Gopal Chandra Panda

- Guru Ramhari Das

Gurus of Odissi Mardala

- Eminent Gurus of Odissi Mardala

- Guru Birabara Sahu, veteran Gotipua exponent

- Guru Basudeba Khuntia

- Guru Rabinarayan Panda

- Guru Maguni Das, veteran Gotipua exponent

- Guru Banamali Maharana, who received a 2004 Sangeet Natak Akademi Award for his contribution to Odissi Music and the Mardala

- Guru Mahadeba Rout, recipient of Odisha Sangeet Natak Akademi Award and 'Pandita' epithet from the Government of Odisha

- Guru Janardana Dash

- Guru Dhaneswar Swain, recipient of Sangeet Natak Akademi Award in the year 2013 for his contribution to Odissi Music and Mardala

- Guru Sachidananda Das, Odisha Sangeet Natak Akademi awardee

- Guru Bijaya Kumar Barik

- Guru Jagannath Kuanr

- Guru Chintamani Raut

- Guru Maheswar Mohapatra

- Guru Gouranga Charan Mahala

See also

- Jayadeva

- Gita Govinda

- Mardala

- Music of Odisha

- Damodar Hota

- Gopal Chandra Panda

- Ramhari Das

- Dhaneswar Swain

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Parhi, Kirtan Narayan (2009). "Odissi Music : Retrospect and Prospect". In Mohapatra, PK (ed.). Perspectives on Orissa. New Delhi: Centre for study in civilizations. pp. 613–626.

- ^ a b Parhi, Kirtan Narayan (2017). The Classicality of Orissi Music. India: Maxcurious Publications Pvt. Ltd. p. 383. ISBN 978-81-932151-2-8.

- ^ Ho, Meilu (2013-05-01). "Connecting Histories: Liturgical Songs as Classical Compositions in Hindustānī Music". Ethnomusicology. 57 (2): 207–235. doi:10.5406/ethnomusicology.57.2.0207. ISSN 0014-1836.

- ^ Patnaik, Kabichandra Kali Charan. A Glimpse into Orissan Music. Bhubaneswar, Odisha: Government of Orissa. p. 2.

- ^ Tripathī, Kunjabihari (1963). The Evolution of Oriya Language and Script. Utkal University. p. 22. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ Mohanty, Gopinath (August 2007). "Odissi - The Classic Music" (PDF). Orissa Review. Culture Department, Government of Odisha. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 10, 2009. Retrieved February 7, 2010.

- ^ Rath, Shantanu Kumar. Mishra (ed.). "Odia Lokanatakaku Ganjamara Abadana" ଓଡ଼ିଆ ଲୋକନାଟକକୁ ଗଞ୍ଜାମର ଅବଦାନ [Role of Ganjam in Odisha's performing art traditions]. Rangabhumi (in Odia). 9. Bhubaneswar: Odisha Sangeet Natak Akademi, Department of Culture, Government of Odisha: 52–64.

- ^ Patra, Sushanta Kumar; Patra, Benudhar. "Archaeology and the maritime history of ancient Orissa" (PDF). Odisha Historical Research Journal. XLVII (2): 107–118. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-10-29.

- ^ a b c d e f Das, Ramhari (2004). Odissi Sangeetara Parampara O Prayoga ଓଡ଼ିଶୀ ସଙ୍ଗୀତର ପରମ୍ପରା ଓ ପ୍ରୟୋଗ [The tradition and method of Odissi music] (in Odia). Bhubaneswar, Odisha: Kaishikee Prakashani.

- ^ a b c Panda, Gopal Chandra (1995). Sri Gita Gobinda Swara Lipi [Notated music of the Gita Govinda] (in Odia). Bhubaneswar: Smt. Bhagabati Panda.

- ^ Samanta, Basudeba (1927). Sangita Kalakara. Manjusa: Srinibasa Rajamani.

- ^ Badajena Mahapatra, Krusnadasa (1983). Panigrahi, Nilamadhab (ed.). Geeta Prakash. Bhubaneswar: Odisha Sangeet Natak Akademi.

- ^ Kavi, M. Ramakrishna (1999). Bharatakosa (A Dictionary to Technical Terms with definitions on Music and Dance Collected from the Works of Bharata and Others). Munshiram Manoharlal. ASIN B00GS1O0H4.

- ^ a b "Culture Department". Orissaculture.gov.in. Archived from the original on 2012-04-03. Retrieved 2012-05-26.

- ^ a b "Orissa Dance & Music". Orissatourism.net. Archived from the original on 2012-05-20. Retrieved 2012-05-26.

- ^ a b Hota, Damodar (2005). Sangita Sastra (in Odia). Vol. 1 (2 ed.). Bhubaneswar: Swara-Ranga. pp. 90–100.

- ^ Parhi, Kirtan Narayan (2007). Odisi Sangita: Kichi Jana Ajana Tathya [Odissi music: Some known and unknown facets] (in Odia). Ink Odisha, Bhubaneswar.

- ^ Panda, Gopal Chandra (December 2011). Odisi Raga Darpana (in Odia). Bhubaneswar.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Odisi Raga Sarani. Bhubaneswar: Odissi Research Centre. 2004.

- ^ Panda, Gopal Chandra (2004). Odisi Raga Ratnabali ओडिसी राग रत्नावली (in Hindi). Bhubaneswar: Bhagavatī Prakāśanī. OCLC 225908458.

- ^ Mohanty, Gopinath (August 2007). "Odissi - The Classical Music". Orissa Review. Culture Department, Government of Orissa: 108–111.

- ^ Ratha, Raghunatha (1976). Patnaik, Kali Charan (ed.). Natyamanorama (in Sanskrit). Bhubaneswar, Odisha: Odisha Sangeet Natak Akademi.

- ^ Chakra, Shyamhari (3 November 2016). "Celebrating an alternate style of Odissi". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- ^ Hota, Damodar (2012). Udra Paddhatiya Sangita (in Odia). Vol. 2. Bhubaneswar: Swara-Ranga. pp. 18–19.

- ^ Chakra, Shyamhari. "Moment of victory for Odissi Mardal". The Samikshya. Archived from the original on 22 May 2022. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ^ Vidyarthi, Nita (6 February 2014). "His own beat". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 22 June 2020. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- ^ Nicodemus, Paul (10 October 2020). "Dhaneswar Swain: A Maestro of Odissi Mardal". The Dance India. Archived from the original on 2020-10-31. Retrieved 2020-12-07.

- ^ "Dhaneswar Swain". Sangeet Natak Akademi. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ^ Chakra, Shyamhari (2020-11-23). "The missionary mardal maestro". The Samikhsya. Archived from the original on 2020-11-24. Retrieved 2020-12-07.

- ^ a b "72-year-old Veena player of Odisha reviving the glory of the instrument". The New Indian Express. 31 August 2019. Archived from the original on 2020-12-05. Retrieved 2020-11-27.

- ^ Pani, Jiwan (2004). Back to the Roots: Essays on Performing Arts of India. New Delhi: Manohar. ISBN 81-7304-560-7.

- ^ Rajan, Anjana (24 April 2009). "Dissenting Note". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- ^ Vidyarthi, Nita (17 October 2013). "Raising his voice". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 28 July 2020.