Mushaf of Ali

| Quran |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Ali |

|---|

|

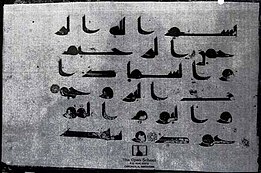

The Mushaf of Ali is a codex of the Quran (a mushaf) that was collected by one of its first scribes, Ali ibn Abi Talib (d. 661), the cousin and son-in-law of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. Ali is also recognized as the fourth Rashidun caliph (r. 656–661) and the first Shia imam. By some Shia accounts, the codex of Ali was rejected for official use after the death of Muhammad in 632 CE for political reasons. Some early Shia traditions also suggest differences with the official Uthmanic codex, though the prevalent overarching Shia view is that the text of codex of Ali identically matched the Uthmanic codex, save for the order of its content. The Twelver Shia believe that the codex of Ali is in possession of their last imam, Muhammad al-Mahdi, who would reveal the codex (and its authoritative commentary by Ali) when he reappears at the end of time to eradicate injustice and evil.

Existence

It is widely believed that Ali ibn Abi Talib, cousin and son-in-law of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, compiled his own transcript of the Quran, the central religious text in Islam. The recension of Ali was perhaps the earliest of its kind.[1][2][3][4] An exception is the Sunni traditionist Abu Dawud al-Sijistani (d. 889) who contends that Ali only memorized the Quran.[3] There are indeed reports that Ali and some other companions of Muhammad collected the verses of the Quran in writing during the lifetime of the prophet,[5] while some other Shia and Sunni reports indicate that Ali prepared his codex immediately after the death of Muhammad in 632 CE.[6][7][3] This preoccupation of Ali with his codex thus justifies in some Sunni sources his widely-rumored absence in the Saqifa meeting where Abu Bakr (r. 632–634) was elected caliph after Muhammad died. The Islamicist Hossein Modarressi therefore suggests that this latter group of reports was circulated to imply consensus over the choice of Abu Bakr.[6]

In his codex, Ali may have arranged the verses in the order by which they were revealed to Muhammad,[8][9] according to the Sunni scholars Ibn Sa'd (d. 845), al-Dhahabi (d. 1348), and al-Suyuti (d. 1505),[9] and the early historian Ibn al-Nadim (d. c. 995).[3] Their account, however, may not be consistent with other reports about the codex, including those by the Shia-leaning historian al-Ya'qubi (d. 897–898) and the Sunni historian al-Shahrastani (d. 1153).[9] The codex of Ali may have also included additional information, either esoteric interpretations (ta'wil) of the verses, according to the Shia scholars al-Kulayni (d. 941), al-Mufid (d. 1022), and al-Tabarsi (d. 1153),[3] or information on the abrogated verses of the Quran, according to al-Suyuti.[9]

The codex of Ali, however, was not widely circulated.[3] By some Shia accounts, Ali offered his codex for official use after the death of Muhammad but was turned down.[9] Such reports are given by al-Ya'qubi and the Shia traditionist Ibn Shahrashub (d. 1192), among others.[10] Alternatively, Modarressi speculates that Ali offered his codex for official use to Uthman (r. 644–656) during his caliphate but the caliph rejected it in favor of other variants available to him. This rejection may have in turn compelled Ali to withdraw his codex in protest, similar to Abd-Allah ibn Mas'ud, another companion who stood aloof when Uthman prepared his recension.[11] As for its fate, it is believed in Twelver Shia that the codex of Ali has been handed down from every imam to his successor, as part of the esoteric knowledge available to the Twelve Imams.[12][13][14] The codex would be finally revealed with the reappearance of their Hidden Imam, Muhammad al-Mahdi,[15] who is expected to eradicate injustice and evil at the end of time.[16]

Differences with the Uthmanic codex

Some Sunni reports allege that the official Uthmanid codex of the Quran is incomplete,[17] as detailed in Fada'il al-Qur'an by the Sunni exegete Abu Ubaid al-Qasim bin Salam (d. 838), among others.[18] Supporting Ali's right to the caliphate after Muhammad, Shia polemists readily cited such reports to charge that explicit references to Ali had been removed from the Quran by senior companions for political reasons.[19]

Yet the accusation that some words and verses were altered or omitted in the Uthmanid codex also appears in Shia tradition.[20][13][21] Such reports can be found in Kitab al-Qira'at by the ninth-century Shia exegete Ahmad ibn Muhammad al-Sayyari,[17][22] even though he has been widely accused of connections to the Ghulat (lit. 'exaggerators' or 'extremists'),[23][24] and a letter ascribed to the Twelver imam Hasan al-Askari (d. 873–874) denounces him as untrustworthy.[23] As the faithful recension of the Quran, the codex of Ali is thus said to have been longer than the official one, with explicit references to Ali and his descendants and supporters,[13] although the actual differences between the two recensions are rarely discussed in sources.[3] This view was popular before the Buyid Era (r. 934–1062) among the Shia scholars,[25] including al-Qummi (d. 919) and probably al-Kulayni (d. 941).[26][25][27] By contrast, any difference between the two codices is rejected by Sunnis because Ali did not impose his recension during his caliphate. The Shia counterargument is that Ali deliberately remained silent about this divisive matter.[28] Fearing persecution for themselves and their followers, the Shia imams who followed Ali may have also adopted religious dissimulation (taqiya) about this issue. In some letters attributed to them by al-Kulayni, the Shia imams also reportedly advised their followers to be content with the Uthmanid codex until the reappearance of al-Mahdi.[29]

Alternatively, the recension of Ali may have matched the Uthmanic codex, save for the ordering of its content,[15] but it was rejected for political reasons because it also included the partisan commentary of Ali,[30] who is often counted among the foremost exegetes of the Quran.[31][3] This is close to the views of al-Mufid (d. 1022), Sharif al-Murtada (d. 1044), and al-Tusi (d. 1067), who were all prominent Twelver theologians of the Buyids period.[32][20] The implication that the Uthmanid codex is faithful has been the prevalent Shia view ever since,[33][3] with some exceptions like the Twelver traditionist Mohsen Fayz Kashani (d. 1777), who nevertheless held that the Uthmanid codex does not miss any legal injunctions.[34] Some Shia scholars have thus questioned the authenticity of those traditions that allege textual differences with the Uthmanid codex, tracing them to the Ghulat,[35][36] or to early Sunni traditions,[36] while Sunnis have in turn accused Shias of originating the falsification claims and blamed them for espousing such views, often indiscriminately.[36][37] The Twelver jurist Abu al-Qasim al-Khoei (d. 1992) and some others have similarly reinterpreted the traditions that may suggest the alteration of the Quran.[38][3] For instance, a tradition ascribed to Ali suggests that a fourth of the Quran is about the House of Muhammad, or the Ahl al-Bayt, while another fourth is about their enemies. The Uthmanic codex certainly does not meet this description but the inconsistency can be explained by another Shia tradition, which states that the verses of the Quran about the virtuous are primarily directed at the Ahl al-Bayt, while those verses about the evildoers are directed first at their enemies.[39]

Footnotes

- ^ Lalani 2006, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Esack 2005, p. 89.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Pakatchi 2015.

- ^ Tabatabai 1975, pp. 42, 63n41.

- ^ Modarressi 1993, p. 16–17.

- ^ a b Modarressi 1993, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Amir-Moezzi 2009, p. 14.

- ^ Lalani 2006, p. 30.

- ^ a b c d e Modarressi 2003, p. 2.

- ^ Modarressi 1993, p. 13.

- ^ Modarressi 1993, p. 14.

- ^ Momen 1985, p. 150.

- ^ a b c Amir-Moezzi 2009, p. 24.

- ^ Amir-Moezzi 2009, pp. 29–30.

- ^ a b Amir-Moezzi 1994, p. 89.

- ^ Amir-Moezzi 1998.

- ^ a b Modarressi 1993, pp. 22, 25–26.

- ^ Amir-Moezzi 2009, p. 16.

- ^ Modarressi 1993, p. 23.

- ^ a b Bar-Asher.

- ^ Momen 1985, pp. 172–173.

- ^ Kohlberg 2009, pp. 31–32.

- ^ a b Kohlberg 2009, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Modarressi 1993, p. 32.

- ^ a b Amir-Moezzi 2009, p. 26.

- ^ Modarressi 1993, p. 33.

- ^ Momen 1985, p. 81.

- ^ Esack 2005, p. 90.

- ^ Amir-Moezzi 1994, pp. 88–89, 204n455.

- ^ Amir-Moezzi 2009, p. 25.

- ^ Lalani 2006, p. 29.

- ^ Amir-Moezzi 2009, p. 27.

- ^ Momen 1985, pp. 77, 81.

- ^ Ayoub 1988, pp. 185, 190.

- ^ Amir-Moezzi 2009, p. 28.

- ^ a b c Modarressi 1993, pp. 36–39.

- ^ Momen 1985, p. 74.

- ^ Ayoub 1988, p. 191.

- ^ Modarressi 1993, p. 29.

References

- Amir-Moezzi, Mohammad Ali (1994). The Divine Guide In Early Shi'ism: The Sources of Esotericism in Islam. Translated by Streight, David. State University of New York Press. ISBN 0791421228.

- Amir-Moezzi, Mohammad Ali (1998). "Eschatology iii. Imami Shiʿism". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. VIII/6. pp. 575–581.

- Amir-Moezzi, Mohammad Ali (2009). "Information, Doubts and Contradictions in Islamic Sources". In Kohlberg, Etan; Amir-Moezzi, Mohammad Ali (eds.). Revelation and Falsification. Brill. pp. 12–23. ISBN 9789004167827.

- Ayoub, Mahmoud M. (1988). "The Speaking Qur'an and the silent Qur'an: A Study of the Principles and Development of Imāmī Shī'ī tafsīr". In Rippin, Andrew (ed.). Approaches to the History of the Interpretation Of The Qur'ān. Clarendon Press. pp. 177–198. ISBN 0198265468.

- Bar-Asher, Meir M. "Shīʿism and the Qurʾān". In McAuliffe, Jane Dammen (ed.). Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān. Brill Reference Online.

- Esack, Farid (2005). The Qur'an: A User's Guide. Oneworld. ISBN 9781851683543.

- Kohlberg, Etan (2009). "Life and Works of al-Sayyārī". In Kohlberg, Etan; Amir-Moezzi, Mohammad Ali (eds.). Revelation and Falsification. Brill. pp. 30–37. ISBN 9789004167827.

- Lalani, Arzina R. (2006). "'Ali ibn Abi Talib". In Leaman, Oliver (ed.). The Qur'an: An encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 28–32. ISBN 9780415326391.

- Modarressi, Hossein (2003). Tradition and Survival: A Bibliographical Survey of Early Shi'ite Literature. Vol. 1. Oneworld. p. 2. ISBN 9781851683314.

- Modarressi, Hossein (1993). "Early Debates on the Integrity of the Qur'ān: A Brief Survey". Studia Islamica. 77. JSTOR: 5–39.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Momen, Moojan (1985). An Introduction to Shi'i Islam. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780853982005.

- Pakatchi, A. (2015). "'Alī b. Abī Ṭālib 4. Qur'ān and Ḥadīth Sciences". In Daftary, F. (ed.). Encyclopaedia Islamica. Translated by Valey, M.I. doi:10.1163/1875-9831_isla_COM_0252.

- Tabatabai, Sayyid Mohammad Hosayn (1975). Shi'ite Islam. Translated by Nasr, Seyyed Hossein. State University of New York Press. ISBN 0873953908.

Further reading

- Kara, Seyfeddin (2024). "Codex of ʿAli". Encyclopedia of the Quran. Brill.