Mother Brook

| Mother Brook | |

|---|---|

A sculpture at Mill Pond Park along the banks of Mother Brook | |

| |

| Etymology | First man-made canal in the United States[1][2] |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Massachusetts |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Charles River |

| • location | Dedham, Massachusetts |

| • coordinates | 42°15′18″N 71°09′53″W / 42.25500°N 71.16472°W Location of the USGS Hydrologic Unit, .4 mi downstream from diversion from Charles River[4] |

| • elevation | 97 ft (30 m) approximate using MapMyRun[3] |

| Mouth | Neponset River |

• location | Hyde Park, Massachusetts |

• coordinates | 42°15′08″N 71°07′23″W / 42.25222°N 71.12306°W |

• elevation | 55 ft (17 m) approximate using MapMyRun[3] |

| Length | 3.6 mi (5.8 km) approximate using MapMyRun[3] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Hyde Park, Massachusetts |

| • average | 23 cu ft/s (0.65 m3/s) |

| • minimum | 0 cu ft/s (0 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 350 cu ft/s (9.9 m3/s) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Hyde Park, Massachusetts[4] |

Mother Brook is a stream that flows from the Charles River in Dedham, Massachusetts, to the Neponset River in the Hyde Park section of Boston, Massachusetts.[2] Mother Brook was also known variously as East Brook and Mill Creek in earlier times.[5][6] Digging the brook made Boston and some surrounding communities an island, accessible only by crossing over water,[7][8][9] making Mother Brook "Massachusetts' Panama Canal."[10]

Dug by English settlers in 1639 to power a grist mill, it is the oldest such canal in North America.[6][11][12][13][a] Mother Brook was important to Dedham as its only source of water power for mills, from 1639 into the early 20th century.[20] For 300 years, it was "the industrial heart" of Dedham.[29]

Today, Mother Brook is part of a flood-control system that diverts water from the Charles River to the Neponset River. The brook's flow is under the control of the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation and is used for flood control on the Charles.[30] There are three remaining dams on the stream, plus a movable floodgate that controls flow from the Charles into Mother Brook.

The brook has given its name to the modern day Mother Brook Community Group,[30][31][b] the Mother Brook Arts and Community Center,[33] Riverside Theatre Works,[34] and the erstwhile Mother Brook Club[35] and Mother Brook Coalition.[36]

Early history

Origins

Dedham, Massachusetts was first settled in 1635 and incorporated in 1636. The settlers needed a mill for grinding corn as hand mills took too much effort.[37][9][38] Wind mills had been tried, but the wind was too unreliable and the North End, where a windmill was moved to in 1632, was too far away.[9] In 1633, the first water powered grist mill was established in Dorchester along the Neponset River at a dam he erected just about the tidal basin.[9][c]

By the late 1630s, the closest watermill was in Watertown, 17 miles away by boat.[38][37] Small amounts of grain could also be milled into flour using labor intensive handmills.[39][d] Neither transporting the grain to distant mills nor producing small amounts in a handmill were attractive options, and so the colonists looked into creating their own mill.[39]

Abraham Shaw who, like many other Dedhamites, came from Watertown, arrived in Dedham in 1637.[20][14] He was granted 60 acres (24 ha) of land as long as he erected a watermill, which he intended to build on the Charles River near the present day Needham Street bridge.[20][40][9][41][29][e] Every man in the town was required to help bring the large millstone to Dedham from Watertown.[20][40][9][41][39][f] Shaw died in 1638 before he could complete his mill, however, and his heirs were not interested in building the mill.[14][12][9][41][29]

Although the initial settlement was adjacent to the Charles, in this vicinity it is slow-moving, with little elevation change that could provide power for a water wheel. A small stream, then called East Brook, ran close by the Charles River, about 100 rods (1,600 feet; 500 metres) from present day Washington Street behind Brookdale Cemetery, and emptied into the Neponset River.[43][12][44] In the spring, the Charles would occasionally flood into a swamp at Purchase Meadow between its banks and East Brook.[45][37][29]

Additionally, East Brook had an elevation change of more than 40 feet on its 3.5 mile run from near the early Dedham settlement to the Neponset River, which was sufficient to drive a water mill.[9][46] However, East Brook had a low water flow insufficient to power a mill.[9][29] The drop in the first mile alone is 45 ft (14 m).[47]

Creation of Mother Brook

A year after Shaw's death the town was still without a mill.[20] A committee was formed and "an audacious plan" was devised to "divert some of the plentiful water from the placid Charles into the steep but scarce East Brook.[9][20][6][41][29] The 4,000 foot ditch was ordered to be dug at public expense by the town on March 25, 1639,[5][20][12][9][41][29][g] and a tax was levied on settlers to pay for it.[9] The settlers may have been influenced by the draining of the Fens in The Wash, an area in England near many of their hometowns.[41][48]

The town was so confident in this course of action that the work began before they found a new miller to replace Shaw.[9] There is no record of who dug it or how long it took.[20][6][29][h] The labor pool would be confined to the 30 men who headed households in the town at the time, plus various servants and other male relatives.[50][41] Tools would have included iron spades, axes, and shovels.[51] Oxen may also have been employed.[48] The earth, clay, rocks, and other excavated materials were then transported overland to create a damn and a mill pond.[48] A sill was also created to control the flow of the water from the Charles into Mother Brook.[48]

While it is unknown when exactly it was completed, there was water running through it by July 14, 1641.[49][6][44][41][29] Orignially called "the Ditch," has been known as Mother Brook since at least 1678.[9][51] There is no record of any celebration that may have taken place upon its completion.[41][29] At a meeting on July 14, 1641, Jonathan Fairbanks, Francis Chickering, and John Dwight were charged with laying out a cartway from the village to the mill.[52]

The work was completed amidst all the other work being done to establish a town out of the wilderness: felling trees, building homes, planting crops, clearing fields, and more.[41][48] Its creation has been called "an inspiring expression of profound communal purpose."[53]

The first mill

The town also offered an incentive of 60 acres of land to whoever would construct and maintain a corn mill, as long as the mill was ready to grind corn by "the first of the 10th month"[i.e. December].[20][9][12][29][i]

The first corn mill was erected in 1641 by John Elderkin, a recent arrival from Lynn, at a dam on East Brook next to the present day Condon Park and near the intersection of Bussey St and Colburn St.[20][54][12][55] Elderkin was given 3 acres of land next to the Brook in return.[51][6] Elderkin was in high demand as a skilled builder and, in 1642, only months after opening the mill, moved out of town.[51][56][j] He sold all of his land to Nathaniel Whiting.[51]

This was the first public utility in the nation.[2] Early settlers could grind their corn at the mill, and in return paid a tithe to help maintain the mill.[2] The town relinquished rights to the brook in 1682[57] and placed an historical marker on the site in 1886.[58]

In 1642, Elderkin sold half of his rights to Whiting and the other half to John Allin, Nathan Aldis, and John Dwight.[9][59][6][56][37][k] They operated the mill "in a rather stormy partnership" until 1649 when Whiting became the sole owner.[56][59][9] The town was displeased with the "insufficient performance" of the mill under Whiting's management.[60][9] In 1652, Whiting sold his mill and all his town rights to John Dwight, Francis Chickering, Joshua Fisher, and John Morse for 250 pounds, but purchased it back the following year.[59]

Whiting and his wife, Hannah, had 14 children. [61] Five generations of his descendants ran their mill from 1641 until 1823, when it was sold.[37][49][61] The family controlled other land along Mother Brook until the 1830s.[61]

Conflict with a second mill

Whiting took sole possession of the mill in 1649 and, that same year, the town began discussing the construction of a second mill.[61] In January 1653, the town offered land to Robert Crossman if he would build a mill on the Charles where Shaw had originally intended.[60] Crossman refused, but Whiting was so displeased by the prospect of a second mill that he offered to sell his mill back to the town for 250 pounds.[60]

For 15 years, there were "many complaints being made by several inhabitants of much damage by deficient grinding of corn at the present mill."[61] As Whiting's performance did not improve, the town wanted an alternative. Daniel Pond and Ezra Morse were then given permission by the town in 1664 to erect a new grist mill on the brook above Whiting's, at the intersection of present day Maverick and High Streets, so long as it was completed by June 24, 1665.[59][62][63][9][61] The new mill was running by 1666, with Morse as the sole proprietor.[64] The new mill was closer to the town center than Whiting's.[61]

Whiting was upset by the competition for both water and customers[9] and, "never one to forgive and forget, Whiting made something of a crusade of opposition" to the new mill.[63][61] Records show that the town spent "considerable time" trying to resolve the issue.[59][61][l] After meeting with the Selectmen, both agreed to live in peace and not interfere with the business of the other.[67][68] Two years later Morse was instructed to not hinder the water flow to such an extent that it would make milling difficult for Whiting.[59][69][9]

The town resolved that "in time of drought or want of water, the water shall in no such time be raised so high by the occasion of the new mill, that the water be thereby hindered of its free course or passage out of the Charles River to the mill. The proprietors of the old mill are at the same time restricted from raising the water in their pond so high as to prejudice the new mill by flowage of backwater."[9] At the same time, Whiting was also told to repair leaks in his own dam before complaining about a lack of water.[59][69][9]

Trouble and disputes, including a lawsuit, continued between the two for 40 years until 1678 when the Town Meeting voted not to hear any more complaints from Whiting.[70][68] Even after Whiting died in 1682, his heirs tried to sue but lost.[68]

In 1699, with the town fed up, Morse's dam was removed, and Morse was given 40 acres of land near the Neponset River at Tiot in compensation.[71][68][9] This seems to have been Morse's idea.[67] He would go on to open a new mill there, in what is today Norwood, Massachusetts, next to a sawmill that Joshua Fisherand Eleazer Lusher opened in 1664.[9][72][m]

At some point in the early 1700s a new leather mill was constructed by Joseph Lewis,[n] Whiting's son-in-law, at the site of the old Morse dam.[76][9][6][68]

New mills at the third privilege

The next mill was constructed in 1682 at present day Saw Mill Lane.[71] Originally requested by Jonathan Fairbanks and James Draper, the privilege was granted to Whiting and Draper instead, likely to avoid any more problems with Whiting.[77][68][71][9] The fulling mill, the first textile mill in Dedham, did not require a dam and the downstream location thus did not pose a threat to Whiting.[68][9]

Whiting died on January 15, 1682, the day the selectmen granted him the privilege.[78][68][79] A condition was attached to this permission, however, that if the town wanted to erect a corn mill on the brook that they may do so, unless Draper and Whiting did so at their own expense.[80][68] Whiting's son, Timothy, signed the agreement with Draper and his son.[68] This mill, like the one above it, was held by the descendants of Nathaniel Whiting for 180 years.[71][9]

A grist mill and a saw mill were later built on the site and were powered by the same waterwheel.[81] The sawmill was built by Timothy Whiting in 1699, but the date of the grist mill's construction was not recorded.[81] One of Whiting's mills burned in 1700, and so the town loaned him 20 pounds to rebuild.[76][67]

Fourth privilege

A fourth mill was established, at present day Stone Mill Drive, just down stream from the third in 1787[82] by two of Whiting's descendants.[9] For a short period of time it produced copper cents, and then was used to manufacture paper.[82] A third of Whiting's descendants opened a wire factory on the same site.[9]

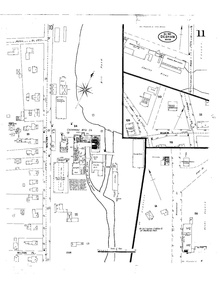

Industrialization of Mother Brook

Eventually, dams and mills were constructed at different times at five locations called "privileges"[o] in Dedham and in what is now the Readville section of Hyde Park, which was originally part of Dedham.[6][83] The first three privileges were granted in the 17th century for purposes that were essential to the local farming community.[83] By 1799, there were two grist mills which were capable of running "in the driest season of the year," two saw mills, a wire mill, and several paper mills with another under construction.[84]

The fourth and fifth privileges were granted in the 18th and 19th centuries, and were for manufacturing.[83] By the mid-19th century, all five privileges had large, industrial textile mills on them.[83]

Mother Brook provided water power at various times for industrial mills of several types, for the manufacture of cotton, wool, paper, wire, and carpets. They also produced corn, fulled cloth, stamped coins, sawed lumber, cut and headed nails, manufactured paper, wove cloth, and leather.[37] The damming of the waterway effected those downstream who wanted to use the water for agriculture, livestock, or other purposes.[83]

By the 1830s, the mills along Mother Brook had been in heavy use for 200 years.[81] They were built very simply to begin with, and after two centuries had become "exceedingly dilapidated relics that attracted the attention of local artists."[81] These artists viewed them as "picturesque artifacts of a simplier and more peaceful past," in contrast to the more modern mills that were spewing smoke and dumping pollutants into the water.[81]

There were mills operating on Mother Brook until some time in the 20th century. At least one mill located on Mother Brook was equipped with a steam engine as an energy source, probably to supplement the water power when the water supply was insufficient but possibly to supplant the water power entirely. The brook may also have served for cooling the steam machinery.

From Mother Brook and the Neponset River out to the Boston Harbor, it was estimated that there was between $2,000,000 and $5,000,000 worth of manufacturing property along the banks in 1886.[8]

Merchant's Woolen Company

By the 1850s, the Merchant's Woolen Company had monopolized all of the water in Mother Brook.[85] In 1870, they were the largest taxpayer in town[86] and, when the New York Times wrote about them in 1887, it described the company as "one of the largest [industrial operations] in the state."[53] The company was no longer under local ownership during this time.[53]

Second privilege

The leather mill was replaced in 1807 by the Norfolk Cotton Manufactory. The local men[87] who invested the funds for the large, wooden, spinning mill,[9] Samuel Lowder, Jonathan Avery, Rueben Guild, Calvin Guild, Pliny Bingham, William Howe, and others,[76] have been described as a "daring group of investors."[86] The mill spun imported bales of cotton, which was then put out to be woven.[86] The fabric was then returned to the mill, finished, and shipped out.[86] As cotton was still new in New England, "the inhabitants felt a degree of pride in having a cotton factory in their town, and whenever their friends from the interior visited them, the first thing thought of was to mention that there was a new cotton factory in the town, and that they must go and see its curious and wonderful machinery."[9]

It was a prosperous company, esteemed by the community, and the annual meetings of the company were marked by festivities.[76] From 1808 through the next decade, the company advertised for labor in the local papers as the work required more manpower than the part-time grist and saw mills that were on the brook before.[86] The company would lend out machines to workers so they could work from home to clean and blend the raw cotton fiber.[87]

During this time period the owners of mills downstream also complained that the Norfolk Cotton Manufactory did not provide enough water downstream for them to use.[88] The complaints continued, despite the creation of a committee in 1811 to look into the matter.[89]

The War of 1812 brought ruin to the company, however, when cheap imports flooded the market.[76][87] The mill was purchased by Benjamin Bussey, "a man of excellent business capacity,"[90] in 1819 for a sum far below cost.[76] Bussey also purchased a mill on the street that now bears his name[91] from the Dedham Worsted Company[p] only three years after they opened. Agreement was made then on the level of the water, and was marked by drill holes in rocks along the banks still visible in 1900.[89]

Fourth privilege

The fourth privilege was used for a variety of purposes in the 19th century, including copper cents, paper, cotton, wool, carpets, and handkerchiefs. In the 1780s another mill, connected by the same wheel, was constructed on the site to produce wire[82] for the new nation's nascent textile industry.[86] The first mill on this site burned in 1809, but was rebuilt with a new raceway and foundation.[82]

The second mill began producing nails in 1814, and five years later its owner, Ruggles Whiting of Boston, sold it to the owner of the first mill, George Bird, who began using the whole site to manufacture paper.[82] In 1823 it switched to cotton, using the machinery of the former Norfolk Cotton Company. In 1835 a new stone mill was erected.[92] It stands today, and was converted into a condominium complex in 1986–87.[6] Unlike the other mills, which were constructed in a strictly utilitarian style, this factory boasted a date stone reading "1835" and a dome-roofed cupola over the mill bell.[86] Together they stood as a testament to the primacy of the mills in the neighborhood.[86][93]

The mill at the fourth privilege, under the ownership of Bussey and with his agent, George H. Kuhn, was among the first to install water-powered broad looms.[93] The looms enabled raw wool to enter the mills, be spun into thread, and then weaved into finished fabric, all under a single roof.[93]

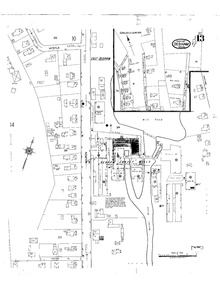

Fifth privilege

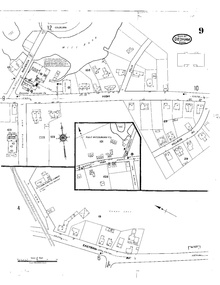

In 1814 a fifth privilege was granted in what was then Dedham, but is today the Readville neighborhood in Hyde Park.[92] Readville, known as early as 1655 known as the Low Plain and then Dedham Low Plain,[9] was settled the same year the privilege was granted[94] when the Dedham Manufacturing Company built a mill there. James Read, one of the original proprietors, was the namesake of the neighborhood when it officially became Readville on October 8, 1847.[9]

Conflict with Charles River mills

As Dedham became industrialized and its economic activity increasingly depended on its water power, so did other communities in the Charles River valley. This led to conflict between the mills on Mother Brook and those using the Charles River downstream from the diversion to Mother Brook.[92] As early as 1767, mill owners in Newton and Watertown petitioned officials for relief from the Mother Brook diversion.[92] A sill was installed to determine the percentage of water diverted into Mother Brook and the percentage to remain in the Charles.[92]

In 1895 it was said that Mother Brook was the

most audacious attempt of robbery ever recorded in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. It was the effort made by Dedham ... to actually steal the river Charles. ... The bold pirates built a canal from the headwaters of the Charles across to the Neponset river, and by widening and deepening this 'mother brook' they were gradually robbing their neighboring town of its beautiful waterway.[95]

Because water diverted from the Charles River through Mother Brook increased the flow in lower sections of the Neponset River, mill owners on the Neponset joined with the Mother Brook mill owners in their defense of the diversion. After a special act of the Great and General Court[96][97][98] the mill owners incorporated as the Mother Brook Mill-owners Association[99] on September 1, 1809.[88] Mill owners on the Charles had formed a similar corporation to advocate for themselves a few months earlier.[97][98] They argued that deviating the flow of the Charles "from its natural course" into Mother Brook violated their rights, and that as a public resource that it deserved state protection.[98]

The Mother Brook Mill-owners Association and their counterpart on the Charles went to the Supreme Judicial Court in March 1809, and petitioned for Commissioners of Sewers[q] to determine the proper amount of water to be diverted into Mother Brook.[97][98] The 1767 sill could not be located, and a new method was established.[97] The Court ruled that one quarter of the Charles could flow into Mother Brook.[9] The Mother Brook mill owners were not happy with this solution, and successfully petitioned the Court to stay their order limiting the amount of water flowing into the Brook.[9]

The Sewer Commission did not present its findings to the Court for 12 years, however, at which time the Mother Brook owners objected and the report of the Commissioners was set aside.[100][101] In 1825, after another court battle, it was determined that the previous agreement was no longer viable due to the length of time taken to file the report and evidence not considered at the time.[102] Work on the issue resumed from 1829 to 1831, and the dispute was finally settled by an agreement among the mill owners on December 3, 1831.[9][103][6] This agreement established that one-third of the Charles River flow would be diverted to Mother Brook, and two-thirds would remain in the Charles for use by downstream owners.[90][37][6] This agreement, which was reaffirmed in 1955,[58] "brought peace to the valley" after decades of conflict.[104] This agreement is still in effect as of 2017.[9]

In 1915 it was estimated that one-third of the water of the Charles River ran through the brook,[5] while in 1938 it was said to be one-half.[105] In 1993, an average of 51 million gallons per day flowed from the Charles into Mother Brook, although that flow can be altered depending on water levels further downstream.[106]

Life along Mother Brook

In the 1800s, as the region and country became more prosperous, mills began to be used for the first time to produce goods not used solely by Dedhamites and those in the immediate area.[76][107] They were so profitable that by the 1820s, landowning farmers were worried about losing control of Town politics.[9][r] The growth of the industrial part of the town was so great that it was said that the factories, dye houses, dwellings, and other buildings associated with the operation of just one privilege "of themselves constitute a little village."[86]

Mill Village

Initially, the mills that sprouted up along Mother Brook only employed two or three people each, and were largely run seasonally.[109] The grist mills would be busiest in the autumn after the harvest, and the saw mills in the winter and spring when leaveless trees could be cut down and transported by sled over snow.[109]

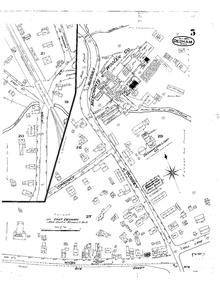

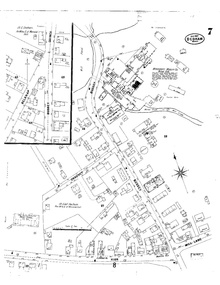

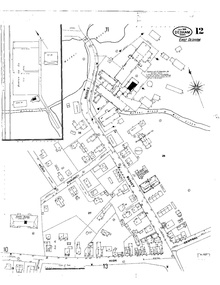

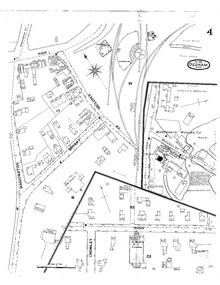

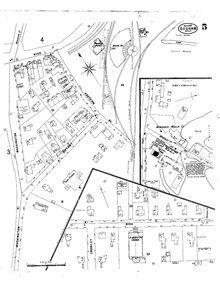

The development of industry spurred the production of housing in the area for the mill workers, and churches, shops, and other businesses followed.[6] For over 100 years, what is today know as East Dedham was one of the most productive and populous areas of town.[85] Maps from the middle of the 19th century show a thickly settled area with a commercial center, homes, stores, and churches.[85]

In 1799, there were three inns, several "elegant mansion-homes," and a number of other houses "very decent in appearance."[84] The population of this Mill Village was growing and the people, about 10 of whom had "the advantage of a learned education," were described as "industrious, affable, and charitable."[84] The East Dedham Firehouse was built in 1855 to protect the area.[6]

In 1870, the Merchant's Woolen Company owned two houses on High Street, five on Maverick, ten on Curve, and two "long houses" on Bussey St.[86] These houses were rented to employees.[86] Several of the homes built during this time to house workers still exist as of 2020.[93] During times of peak production, Merchant's Woolen Company employed about 1,000 people, almost all of whom were immigrants.[85]

Benjamin Bussey build a number of boarding houses, including what is today 305 and 315 High Street and 59 Maverick Street.[93] The two buildings on High Street were originally connected by an ell.[93] In 1829, the ten men who lived in them paid $1.50 per week and the 15 "girls" each paid $1.25.[93]

Immigrants

The mills began to attract immigrants from Europe and Canada who came to America seeking employment and a better life.[85][107] In 1827, it was clear that the industrialization of the waterway was going to attract new workers to work in the mills.[53] The Irish came beginning with the Great Famine in the 1840s, and the Germans followed in the 1850s.[107] Italians and other immigrants began arriving in large numbers at the end of the century.[107]

Working conditions

Working in harsh conditions, many of those who came to Dedham only stayed for a short period of time and then moved on.[107] Mill employees worked six days a week, 12 hours a day, starting at first light.[85]

In the early part of the century, there were only two holidays a year: the Fourth of July and Thanksgiving.[85] When Catholics began arriving, they refused to work on Christmas.[85] At first Protestants performed the dirty tasks such as cleaning the privies that the Catholic employees typically did, but around 1860 it became a holiday for all.[85]

20th century and the decline of industry

In 1900,[14] and even 1915, after "275 years of constant usefulness," the brook made up "the source of the principal business of the town [of Dedham]."[20] Though the mills remained open into the 20th century, they were not immune from the larger economic forces at play. In the late 1800s they began "losing ground in the national economic picture, inexorably sliding into an increasingly marginal sort of operation, and finally succumbing entirely to the slump which followed the First World War."[110] Beginning in the 1910s and 1920s they began to close as the textile industry was in decline,[9] and by 1986 the cotton mills and brick factories that once lined the brook were "long-gone."[111][6]

In the 1960s, the pond at the fifth privilege had been drained, and the land owner wanted to build a strip mall on the site.[9] The Department of Conservation and Recreation purchased the land instead.[9] They cleaned up a junkyard, dredged out silt and fill, rebuilt the dam, and published a plan to promote boating, hiking, and other outdoor activities on the site.[9] It also spoke about building a bathhouse, assuming the water quality improved.[9] When the Dedham Mall was built in the 1960s, part of the Brook was piped underground.[6]

The sill placed at the mouth has since been replaced with a mechanical floodgate that can be raised or lowered depending on water levels in the Charles.[9] There is a small brick building on the site with the floodgate controls.[9] It was proposed in 1978 to use the three remaining dams on the bridge to generate hydroelectric power.[112] In 2009, the Dedham Selectmen proposed designating the brook as an historic waterway to better qualify for grants.[113]

Pollution

During the early 1900s, the state Board of Health began enforcing pollution regulations that prevented additional manufacturing enterprises from setting up along the brook, having "resolutely set its decision against the pollution of this stream."[10][114] One plant was required to install an expensive filtration system to clean its liquid waste before dumping it in the waterway.[114]

In 1910 the water being pumped by the Town of Hyde Park at Mother Brook was deemed unsafe for use without first boiling,[115] and in 1911 that Town applied to be hooked up to the metropolitan water system.[116] By 1944 the Neponset was said to be "loaded with putrefacation."[10]

When marshlands were reclaimed in the 1960s[117] it was for partially for the purposes of flood control.[118] One of those reclaimed areas was where the Dedham Mall now stands, very near the headwaters of the brook. The runoff from that 150-acre (61 ha) development, however, flowed into the brook and then the Neponset, which could not handle the extra water during heavy rains.[119]

By the mid-20th century, "after over 300 years of industrial use, the Mother Brook was intensely polluted." Gasoline, PCPs, and even raw sewerage had been dumped into the Brook over the years.[9] An oil spill of 1,300 gallons was discovered near Milton Street in 1975,[120][121][9] and gasoline was discovered bubbling into the brook in 1990.[122] L. E. Mason Co. was fined $250,000 by the Environmental Protection Agency for dumping trichloroethylene into the brook from 1986 to 1994.[123] The company was also known to dump zinc, fats, oils and greases into the waterway.[123]

During the 1990s a science teacher at Dedham High School and her chemistry students ran water quality tests on the brook.[124][125] She found that water quality is good, though fecal coliform counts allow only partial body contact.[125] While great progress has been made, in 2017 Mother Brook remained one of the most polluted tributaries to the Neponset River.[9] Unlike most waterways in the Neponset watershed, Mother Brook is less polluted during heavy rains than during drier times, due to the abundance of clean Charles River water flowing into it.[9]

Cleanups and maintenance

After centuries of industrialization and dumping, Mother Brook became quite polluted.[30] Cleanups have been organized by a number of groups in recent decades.[30][126]

In 2007, the brook was redirected under Hyde Park Avenue by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts to clean up the PCBs that had previously been dumped into the water.[127] That cleanup led to a federal lawsuit over who would pay for the cost of the remediation.[127] Ten years later, in 2017, the Department of Conservation and Recreation unveiled plans to remove several trees and overgrown vegetation close to the diversion point at the Charles River in order to stabilize and protect the dam controlling the flow of water from the river into the brook.[128]

Modern day

Today along the banks of the brook are walking trails, a picnic area, a canoe launch,[30] Condon Park, a handicapped accessible playground, and more. The Mother Brook Community Group won a grant from Dedham Savings to turn the old Town Beach at the intersection of Bussey and Colburn Street into a passive park with an observation deck, benches, landscaping and a stone path. Mill Pond Park opened on July 12, 2014.[129][130] The Community Group has also opened more areas of the Brook back up to fishing, and the catches are safe to eat in moderate amounts.[30]

In 1961, an incinerator was opened at the site of the old bathhouse.[131] It was eventually converted into a trash transfer station, but was shut down in 2019.[131] After closing, the Town's Department of Public Works used it for storage and, in 2024, a survey was taken of Town residents of what they wanted to see in a future use of the site.[131]

At the 2015 Fall Annual Town Meeting, the town established the Mother Brook 375th Anniversary Committee. Serving on it were Dan Hart, Nicole Keane, Brian Keaney, Vicky L. Krukeberg, Charlie Krueger, Gerri Roberts, and Jean Ford Webb.[6]

National Register of Historic Places

In the 2010s, the Mother Brook Community Group, the East Dedham neighborhood association, began a campaign to get Mother Brook listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[44][132][133][134] The results of the first phase of the effort, an architectural study of the Brook and adjourning areas, was completed by Heritage Consultants and presented in January 2020.[44][132][133][134] The consultants discovered over 70 buildings, areas, and structures still standing that relate in some way to the history of the mills.[44] They include

- 202 Bussey St. which was originally built circa 1855 as the Merchant Woolen Company's Factory Mill Number 2.[44] It originally housed a carpenter's shop with spinning machines on the upper floors.[44]

- Two private homes on Maverick and High Streets that were built as boarding houses for workers of the Maverick Woolen companies circa 1825.[44] Room and board at these establishments cost $1.50 a week for men and $1.25 in 1829 when there were ten men and 15 women living there.[44]

- Brookdale Cemetery, which was built to accommodate a swelling population that moved to town to work in the mills.[44]

The consultant's research was submitted to the Massachusetts Historical Commission who will determine whether Mother Book qualifies for the National Register listing.[44]

Accidents and floods

Floods

In 1886, waters flooded their banks and put the dams, and the one at Merchant's Mill especially, in danger of breaching.[135][136] There were fears that a dam in Dover would give way, and the resulting rush of water would destroy the Dedham dam.[8] Prior to this Merchant's Mill was considered impregnable.[8] It was one of the greatest floods Dedham Center had ever seen.[136]

Streets in the Manor section of Dedham had water two to three feet deep when the brook flooded in March 1936.[137] Rain and melting snow caused the Charles and Mother Brook to flood their banks in 1948, putting some parts of Dedham under water.[138]

Ice chunks at two of the dams caused flooding in 1955.[139] Firefighters sprayed high pressure water at the ice jam off Milton Street, and a crane scooped out debris from the dam and broke the ice at Maverick Street.[139] The water level dropped two feet that day as a result.[139]

Later that year, during the worst floods in New England's history, 150 people in Hyde Park had to evacuate their homes after flood waters from Mother Brook and the Neponset River collapsed preventative embankments.[140] Mayor John Hynes led an inspection party to survey the damage.[141] Roads, including the V.F.W. Parkway, were flooded in Dedham.[142] That fall the state approved $2 million for flood control in Mother Brook and the Neponset.[143][144][145] Another $2 million was approved by the Massachusetts House of Representatives in 1960.[146]

A team of 120 men descended on Hyde Park at the junction of the Neponset and Mother Brook with 1,200 sandbags to prevent flooding in March 1958.[147] The water was already threatening homes and roads in January of that year.[148] At least "a couple hundred" residents along the Charles, Neponset, and Mother Brook had to be evacuated when those rivers flooded in 1968.[149] The worst area in town was along Bussey St, along the brook.[149]

1938 flood

In 1938, while much of the Charles and Neponset Rivers were flooding their banks and causing $3,000,000 in damage,[150] the area around Mother Brook was unharmed in the early days of the surge.[105] Dams along the brook controlled the heavy flow of water[151] which were said to be 15,000 cubic feet per second.[152] It was close to the level of the 1936 flood, but six inches below the flood of 1920.[152]

Scores of homes in low-lying areas eventually had their basements flooded,[152] and the wooden bridge at Maverick Street was threatened.[153] Sandbags, an oil truck, and granite slabs were placed on the bridge to keep it from washing away.[154] The Boston Envelope Company, located next to the bridge, had their first floor flooded.[154]

Three young men who tried to canoe down the Charles during the 1938 flood were overturned in a whirlpool and were swept down the swollen Mother Brook.[150] They were saved after an East Street rescuer ran 500 yards and tossed them a garden hose.[155]

Drownings and rescues

Over the years there have been a number of accidents on the brook, including some resulting who drowned.[s] In December 1905, a 12-year-old boy named James Harnett drowned while skating across ice only half an inch thick on Mill Pond.[169] His brother William, 17, rushed to save him, but both ended up in the water.[169] The older brother was saved by a human chain of other skaters, while the younger boy's body was recovered by police an hour later.[169]

An 8-year-old boy fell through the ice and was under water for 20 minutes in 1980.[170] A passing motorist[170] and three others[171] dove in the brook, but were not able to locate him.[170] A WHDH radio traffic helicopter broke the ice with its pontoons, allowing Boston firefighters to spot and recover David Tundidor's body.[170] He was in a medically induced coma,[172] but died four days later.[171]

Others have been more fortunate, and were able to be rescued.[t] After sneaking out of the house in July 1899, 13-year-old William Dennen dove off a bridge near his house on Emmett Ave to save the life of 7-year-old Mary Bouchard, who had fallen in.[179] John F. McGraw, a 33-year-old Scottish immigrant, attempted suicide by drowning in the brook in 1916.[180] After going over a dam and landing in shallow water, the father of three climbed onto shore and was taken to the psychiatric hospital for evaluation.[180] Paul Flanagan, 23, survived for 3.5 hours in the water after his car plunged into the brook in February 1983.[181] He was brought to Norwood Hospital with hypothermia and was later released.[181]

Two boys claimed to have found a human leg in the brook in 1937,[182] but police could not find either the leg or the body.[183]

Other events

In April 1878, a "balky horse" sent six people into the brook, but none were injured.[184] A similar incident occurred in 1837 when a thirsty horse brought himself, the teamster driving him, and the load of paper he was carrying from the mills in Dedham to Braintree into the brook.[185]

Moments after leaving Dedham Square for Forest Hills in 1911, a streetcar jumped the track on Washington Street and dangled 35 passengers over the brook.[186] Only two minor injuries were reported.[186] A cat was saved from a flooded culvert in 1938 by a team of neighborhood boys after the Dedham Fire Department was unable to do so.[187] A 13-year-old boy, William Sullivan, was kneeling on a raft in 1956 behind Brookdale Cemetery when his friend accidentally shot him in the leg with a .32 caliber gun.[188]

Mills

First privilege

The first privilege was located next to present day Condon Park, corner of Bussey St and Colburn St.

| Year | Owner | Manager | Product | Notes | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1641[43] | John Elderkin | John Elderkin | Corn | ||

| 1642[59] | 50%: Nathaniel Whiting, 50% John Allin, Nathaniel Aldis, John Dwight | ||||

| 1649[59] | Nathaniel Whiting | Nathaniel Whiting | |||

| 1652[59] | John Dwight, Francis Chickering, Joshua Fisher, John Morse | Sold for 250 pounds | |||

| 1653[59] | Nathaniel Whiting | Nathaniel Whiting | |||

| 1821[76] | Dedham Worsted Company | Worsted | |||

| 1824[82][189][190] | Benjamin Bussey | Thomas Barrows was superintendent and George H Kuhn was treasurer.[189] | Wool | Bussey erected machine shops, dye houses, and dwellings at both of his mills. Privileges 1 and 2 under common ownership during this time. | |

| 1843[90] | J. Wiley Edmunds | ||||

| 1843[90] | Maverick Woolen Company | Thomas Barrows[u] | |||

| 1863[90] | Merchants Woolen Company |  | |||

| 1895[193] | Edward D. Thayer[v] |  | |||

| 1909[194][195][196][197] | Hodge's Finishing Company | Fred H. Hodges[w] | Bleach and Finish Cotton Pieces;[194] Metal and Rubber Faced Type[198] | Employed 50 people, had six boilers, produced 35,000 yards per day, and had an office in New York City at 320 Broadway.[194] |  |

| 1938–Present Day[9] | Condon Park | N/A | After closing, the Hodges' factory sat empty for 20 years.[107] The walls of the Hodge's factory were knocked into the foundation and Condon Park was constructed over it.[132][107] As of 2020, Mill #2 at 202 Bussey St is all that remains of the complex.[107] It housed the carpentry shop on the first floor and spinning frames on the upper levels.[107] |   |

Second privilege

The second privilege was located at present day Maverick Street.

| Year | Owner | Manager | Product | Notes | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1664[59] | Ezra Morse | Ezra Morse | Corn | Removed in 1699[71] | |

| Early 1700s[76][9][199][68] | Joseph Lewis | Leather | |||

| 1807[76][199] | Norfolk Cotton Manufactory | Cotton | Ruined by War of 1812 | ||

| 1819[76][200][190] | Benjamin Bussey | Thomas Barrows was superintendent and George H Kuhn was treasurer.[189] | Wool | Bussey erected machine shops, dye houses, and dwellings at both of his mills. Privileges 1 and 2 under common ownership after 1824. | |

| 1843[90] | J. Wiley Edmunds | ||||

| 1843[90] | Maverick Woolen Company | Thomas Barrows[x] | |||

| 1863[90] | Merchants Woolen Company |  | |||

| 1895[193] | Edward D. Thayer |  | |||

| Between 1909[114] & 1917[202] | Dedham Finishing Company |  | |||

| 1936[203][y][200] | Boston Envelope Company | Envelopes | Could produce 800,000 envelopes a day when it opened.[203] The company owned and maintained a park on the other side of Maverick Street, at the corner of High.[200] Mill Pond, which sits downstream from the factory, would become colored when the factory dumped die into the water.[107] | ||

| Present Day[9] | AliMed | Medical products and supplies |  |

Third privilege

The third privilege was located at present day Saw Mill Lane.

| Year | Owner | Manager | Product | Notes | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1682[71][9] | Nathaniel Whiting and James Draper | There were several mills on the site. The first was for fulling, which by the mid 1800s was partially used for cabinet making and possibly hat making.[75] Later were added a grist mill and, around 1700, a saw mill.[204] | Whiting died on the day the selectmen granted him the rights to erect a mill on the site.[78] Whiting's descendants owned the mill for over 180 years. | ||

| 1682-1863[205] | Descendants of Nathaniel Whiting | ||||

| 1863[205] | Edmunds and Colby[z] | ||||

| 1864[205][206] | Thomas Barrows | Between 1868 and 1885, first Charles C. Sanderson then Goding Brothers |  | ||

| 1872[205] | Merchants Woolen Company | ||||

| 1875[205] | Royal O. Storrs & Company | ||||

| 1883[205] | Merchants Woolen Company | Saw and grist mill | When they went out of business, it was the first time in 240 years there was no grist mill on Mother Brook | ||

| 1885[109] | The old mills were torn down, the dam removed, and the privilege merged with the fourth privilege. | ||||

| 1894[207][109] | J. Eugene Cochrane | N/A | Closed and merged with the fourth privilege. | Third and fourth privileges under common ownership. By this time, there was little left of the former mills except the raceways and a few wheels left standing in the water. | |

| 1897[208] | Cochrane Manufacturing Company | ||||

| Present day[9] | Strip mall and Dunkin Donuts |

Fourth privilege

The fourth privilege's first mill was located at present day Stone Mill Drive.

| Year | Owner | Manager | Product | Notes | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1787[82][209] | Joseph Whiting, Jr., Paul Moses, Aaron Whiting | Copper blanks to be turned into pennies | |||

| ~1790[82][209] | Hermann Mann | Paper | |||

| 1804[82][209] | George Bird | Burned and rebuilt in 1809 | |||

| 1823[82][200] | George Bird and Frederick A. Taft | Norfolk Manufacturing Company | Cotton | Taft was an experienced cotton manufacturer from Uxbridge, Massachusetts.[93] He consolidated several properties at the site in the 1820s using investors from Boston and gave control to his brother, Ezra W. Taft, a Dedham resident.[93] By 1827, between 200 and 300 workers produced 50 to 60 bolts of cloth each week.[93] The machines ran 14 hours a day.[93] Used the machinery of the Norfolk Cotton Factory at the first privilege. | |

| 1830[82] | Norfolk Manufacturing Company | John Lemist and Frederick A. Taft | |||

| 1832[210] | John Lemist and Ezra W. Taft | In 1835, the stone mill which now stands upon the site was erected using Dedham Granite[93] and was supplied with new machinery for the manufacture of cotton goods.[210] The original building stood three stories high and measured 100' long by 40' wide.[93] It had a gable roof with a clerestory monitor that brought light into the attic.[93] The stone bell tower was capped with columns supporting a domed cupola.[93] The Corporation prospered under Mr Taft's management.[210] By the middle of the century it was producing 650,000 yards of cotton a year.[93] Ezra W. Taft continued to be the agent and manager of the corporation for about 30 years.[210] An unused building nearby was used by Edward Holmes and Thomas Dunbar beginning in 1846 for their wheelwright business using steam power.[211] Taft's paper mill mill burned on July 17, 1846.[212] | |||

| ~1835[92][213][214] | James Reed and Ezra W. Taft | ||||

| 1863[205][200] | Thomas Barrows[aa] | Wool | Barrows enlarged the mill[205][214] and installed turbines and a steam engine.[15] | ||

| 1872[205] | Merchants Woolen Company | ||||

| 1875[205] | Royal O. Storrs and Frederick R. Storrs | Went out of business | |||

| 1882[205] | Merchants Woolen Company | ||||

| 1894[207][200] | J. Eugene Cochrane | Carpets and handkerchiefs | Third and fourth privileges under common ownership | ||

| 1897[208] | Cochrane Manufacturing Company | Norfolk Mills |  | ||

| After 1917[15][114][217] | Closed |  | |||

| Before 1927[218][219][220] | United Waste Company | Wool, reclaimed fabric,[220] and cloth recycling[15] | This was the final industrial use of the property.[200] | ||

| 1930s[214] | Shoddy wool | ||||

| 1986[15][221][214][6] | Bergmeyer Development Co. | Re-purposed for 86 condominiums[ab] | Purchase price was $1.6 million.[15] A 25' waterfall runs through the complex.[30] Fires burned various sections of the complex in the 1980s.[107] |  | |

| Present day | Stone Mill Condominiums[9][107] |    |

The fourth privilege's second mill was located at present day Stone Mill Drive.

| Year | Owner | Manager | Product | Notes | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ~1787[82][209] | Ruggles Whiting | Wire | |||

| 1814[82][209] | Nails | ||||

| 1819[82] | George Bird | Paper | Bird already owned the first mill at the fourth privilege |

Fifth privilege

The fifth privilege was located at the corner of Knight St. and River St. in Readville.[222]

| Year | Owner | Manager | Product | Notes | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1814[92][9] | Dedham Manufacturing Company | Cotton | Original buildings made of wood | ||

| 1867[208] | Nine men[ac] | ||||

| 1875[208] | Smithfield Manufacturing Company | Built brick mills, and lost them to the mortgager | |||

| 1879[208] | Royal C. Taft | ||||

| 1879[208] | B.B. & R. Knight Cotton | Manchaug Company | Rebuilt the dam, put in new wheels, and made other improvements. | ||

| 1922[223] | Francis W. Smith | The mill was expected to be closed and leveled.[ad] | The main building of the plant is of brick, measuring 331 feet long by 59 feet wide on average.[225] The sale included several other parcels and buildings, including tenements and a superintendent's house.[223][ae] | ||

| Condominiums[107] | |||||

| Present day[9] | Part of Stony Brook Reservation |

Bridges

Today, after diverting from the Charles, Mother Brook immediately runs under a bridge on Providence Highway. When it was constructed, a tablet was erected on the bridge commemorating the brook.[226] Shortly thereafter it runs under a culvert at the Dedham Mall before appearing again at the transfer station and running to the Washington Street Bridge. It then crosses under Maverick Street, Bussey Street, and Saw Mill Lane, sites of three old mills. Within the Mother Brook Condominium complex, just downstream from Centennial Dam, the brook runs under a small bridge that connects North Stone Mill Drive and South Stone Mill Drive. After entering Hyde Park, it runs under bridges at River Street and Reservation Road, before merging with the Neponset.

Various improvements to the bridges have been proposed and carried out over the years by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, the Town of Dedham, the City of Boston, and private interests.[af]

Recreation

For many years, Mother Brook was a popular boating, bathing, and ice skating destination.[20][245][9][6] According to one contemporary, in the winters of the 1870s and 1880s the "youth then gathered on the ice [to ice skate] must have numbered in the hundreds."[6]

Swimming

A public bath house was constructed in 1898 at a cost of $700 on what is today Incinerator Road at the Dedham Mall.[246][131] The Brook would be dredged in this area occasionally to create better swimming conditions and the Town maintained the beach area.[131]

While Dedham had a Commissioner of Mother Brook[152] during the early 20th century, the Planning Board was responsible for the recreation aspects of the brook, appointing a special police officer and life-saver,[131][247] and running swimming and diving competitions.[248]

In 1907, afternoons on Tuesdays and Fridays were set aside for women's use.[245] Girls 16 and under were allowed in free, while those older were charged 5 cents.[245] The youngest member of the Parks Commission, J. Vincent Reilly, taught crowds of more than 200 how to swim.[245]

While the Town provided a dock in the water for bathers to jump off of, some would jump off of the New York, New Haven, and Hartford railroad bridge that ran across the Brook on its way to Dedham station.[131]

The bathhouse burned down in 1923,[249] and a proposal in 1924 to rebuild it was expected to receive an unfavorable recommendation from the Warrant Committee.[250] A new one was constructed in 1925.[131]

By the 1940s, games and swim meets were held at the bathhouse at the end the summer.[131] The swimming competitions drew crowds of 800.[251] The bathhouse closed at the end of the summer of 1952 out of concerns that the water was too polluted.[131]

The swimming area at present day Mill Pond Park was considered a perk of working at the Boston Envelope Company in 1936.[203]

Boating and fishing

A canoeist in 1893 wrote of his trip down the brook that upon entering from the Charles he

bid adieu to the flat marshlands and broad views of the farther river, for the little brook caries us thought varied scenery now by a barnyard with it lowing cattle, ducks splashing and dibbing in the water and a dilapidated old carryall backed into the stream, left to wash itself, and then into the cool woodlands, where we can almost touch the banks on either hand. And the green alder bushes arch over our heads, forming a cool and shady tunnel.

The water is so shallow that we see plainly the brilliantly colored pebbles on the bottom and daintly hued little fish darting hither and thither. It is a busy, brawling stream and hurries on to join the Neponset, industriously turning the numerous mills on the way.[252]

In at least the 1930s[253] and 1940s,[254] the state Division of Fish and Game stocked the brook with trout for fishing. The banks were lined with fishermen during parts of 1941.[255]

Open space and parks

Future Supreme Court justice Louis D. Brandeis wrote to William Beltran De Las Casas, the Chairman of the Metropolitan Park Commission, in 1905, asking him to consider including the brook in the Metropolitan Park System of Greater Boston.[256] He said "unique in the metropolitan district. It is quite like the Main woods."[256] He added that if it was added, though it is separated from the rest of the parks, "the future interests of our metropolitan park system would in my opinion be greatly subserved."[256] De Las Cas agreed with Brandeis, but the mill owners in the area threatened to sue to prevent the action, and the costs of taking it by eminent domain were high.[256]

In 1915 it was said that well-kept gardens could be seen along both sides of the length of the brook.[19][20]

In 1968 the Metropolitan Park Commission applied for an "Open Spaces Grant" from the federal government, during which time part of the area near the headwaters were being drained to build the Dedham Mall.[256] The Boston Natural Areas Fund conserved a lot along the brook in 1980 as "green relief from massed buildings and pavement."[257] The City of Boston built a new park on Reservation Road in 1999, shoring up the banks of the brook while they worked.[258] The project on the six acre site included a skateboard park, a landscaped nature area along the brook, and a cleanup of contaminants.[259][260]

Notes

- ^ This canal has been described as the first man-made canal in the United States since at least the 1840s.[14][1][2][5][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26] Remains of much older canals dug by the Hohokam people have been uncovered in Arizona, although these are irrigation canals, not power or hydraulic canals like Mother Brook.[27][28]

- ^ The Mother Brook Community Group was founded in 2008.[32]

- ^ As of 2017, this site is where the Adams Street bridge crosses the river.[9]

- ^ A handmill likely brought over from England by John Farrington is today in the collection of the Dedham Museum and Archive.[39]

- ^ The site was discovered in the 1840s when excavations on the site uncovered the remnants of a millrace.[29]

- ^ Another condition of the grant was that if Shaw ever sold the mill, the town would have the right of first refusal to purchase it back from him.[42]

- ^ "Ordered yt a Ditch shalbe made at a comon charge thrugh purchashed medowe unto ye East brooke yt may bother be a ptieon fence in ye same; as also may serve for a course unto a water mille; yt it shall be found fitting to set a mille upon ye sayd brooke by ye judgement of a workman for yt purpose."[20][9][6]

- ^ Whiting family history claims it was done by Nathaniel Whiting.[49]

- ^ Before the adaptation of the Gregorian calendar in the United States, the year did not begin in January.

- ^ He went on to build mills, meetinghouses, and wharves around New England.[51]

- ^ Allin was the minister, Aldis the deacon, and Dwight was Whiting's father-in-law.[60]

- ^ The third paragraph of the Town Covenant stated: "That if at any time differences shall rise between parties of our said town, that then such party or parties shall presently refer all such differences unto some one, two or three others of our said society to be fully accorded and determined without any further delay, if it possibly may be."[65][66]

- ^ Fisher's mill is now on the seal of Walpole, Massachusetts.[73][74]

- ^ Neiswander has the Lewis' first name as John.[68] He was a landowner on Mother Brook as early as 1680.[75] His house was at the third privilege, next to the grist mill.[75]

- ^ A privilege would be called a "permit" in modern parlance.[83]

- ^ Incorporated principally by William Phillips and Jabez Chickering.[76]

- ^ Elijah Brigham of Westboro, Jonas Kendall of Leominster, and Loammi Baldwin of Cambridge were appointed by the Court in October 1809.[97]

- ^ There were two competing power structures for the farmers, the "influx of lawyers, politicians, and people on county business," after Dedham was named the shiretown in 1793,[108] and those who owned and worked in the mills.[9]

- ^ Deaths include Michael Ansbro in 1892,[156] John J. Carroll in 1948,[157] Timothy Neville in 1967,[158] and James Colburn.[159] Many were children, including 8-year-old William Hickey in 1899,[160] 14-year-old James Cox in 1969,[161] 2-year-old Fritz Wende in 1927,[162] a 6-year-old boy in 1946,[163] 14-year-old Daniel Linehan in 1951,[164] 2-and-a-half-year-old James Cunningham in 1959,[165] and 13-year-old William Molineaux in 1972.[166] Several children died after winter ice broke, plunging them into the cold water. These include an 8-year-old boy in 1895,[167] and a 7-year-old boy in 1929.[168]

- ^ Those who were rescued include Katie Murray, a 20-year-old, in August 1875,[173] and a six-year-old boy was rescued after falling in August 1878 by Arthur Bacon, "a young man who has previously acted in a like noble manner."[174] Also saved was 11-year-old Thomas Mahoney in 1919,[175] 14-year-old Maud Conant in 1925,[176] and a 12-year-old boy floating on a bale of cotton waste in 1953.[177] In 2009, a man was rescued by the Dedham Fire Department after his homemade boat went over the damn that separates the Charles from the brook.[178]

- ^ In 1851, Barrows was the wealthiest mill owner in town.[191] He was a vice president of the dinner celebrating Dedham's 250th anniversary.[192]

- ^ It was closed by 1909.[114]

- ^ Chas. О. Brightman, Pres Fred H. Hodges, Sec and Supt.; Frank B. Hodges, Treas. and Buyer.[194]

- ^ William H. Mann was the bookkeeper. He lived on Court Street. He also played the organ at the First Church and Parish in Dedham, St. Paul's Church, and at the Baptist Church in East Dedham.[201]

- ^ It closed before 1976 as Hanson refers to it as "the old Boston Envelope Company Building."[63]

- ^ "The third privilege owned by the Whiting heirs was purchased under an assignment of William Whiting to Messrs Colburn & Endicott by Messrs Edmunds & Colby in 1863 at which time the Merchants Woolen Company was formed."[205]

- ^ Barrows had an estate on High Street that was torn down in 1959 to make room for St. Mary's parking lot.[215][216]

- ^ The general contractor was the Kaplan Corp., the landscape architects was Weinmayr Associates, and the financing was provided by the Mutual Bank.[15]

- ^ A company of men composed of Tully D. Bowen, Earle P. Mason, Henry Waterman, John A. Taft, Stephen Harris, Cyrus Harris, Joseph Woods, John A. Adams, and Benjamin Sibley[208]

- ^ It was, in fact, closed sometime prior to 1927, as were many others, in a "textile depression."[224]

- ^ The equipment in the main building included an automatic opener, five lapper machines, 108 cards, 7 drawing frames, 29 fly frames, 77 spinning frames, 5 pair of mules, 15 spooling frames, and warper frames, a slasher, 508 plain looms, cloth room equipment, a waste picker house unit, machine shop equipment, etc. In addition there was a quantity of cotton machinery which was never a part of this plant and was encased and marked for shipment to Japan, including openers, cards ring, spinning frames, mules winders, reels, and bobbins.[225]

- ^ See, for example:[227][228][229][230][231][232][233][234][235][236][237][238][239][240][241][242][243][244]

References

- ^ a b Hayward, J. (1847). A Gazetteer of Massachusetts. Hayward. p. 135.

- ^ a b c d e "Where Growth Centers". The Salina Evening Journal. Salina, Kansas. November 6, 1922. p. 13. Retrieved March 17, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "Mother Brook in Dedham, MA". MapMyRun. Retrieved 2013-09-16.

- ^ a b "USGS 01104000 MOTHER BROOK AT DEDHAM, MA". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2013-09-16.

- ^ a b c d "What People Talk About". The Boston Daily Globe. May 22, 1915. p. 10. Retrieved March 17, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u In Celebration of the Construction of the Mother Brook in Dedham, Dedham Historical Society, September 2016

- ^ "Wants of the City". The Boston Post. April 24, 1874. p. 3. Retrieved March 17, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d "The Floods". The Fitchburg Sentinel. Fitchburg, Massachusetts. February 16, 1886. p. 2. Retrieved March 17, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk Sconyers, Jake and Stewart, Nikki (December 18, 2017). "Episode 59: Corn, Cotton, and Condos; 378 Years on the Mother Brook". Hub History (Podcast). Retrieved December 26, 2017.

{{cite podcast}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c "Rivers of Massachusetts". The Boston Globe. Jul 27, 1944. p. 12. ProQuest 840010705. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ Tager, Jack; Herman, Jennifer L. (December 1, 2008). Massachusetts Encyclopedia (2008–2009 ed.). North American Book Dist LLC. p. 201. ISBN 9781878592651.

Dedham is watered by Charles River on its western border, by Neponset River on the east, and by Mother Brook (a canal or artificial river of about three miles in length passing from the Charles to the Neponset); this was the first canal made in the United States, completed within ten years after the first settlement of Boston.

- ^ a b c d e f Hanson 1976, p. 27.

- ^ Parr 2009, p. 18.

- ^ a b c d Worthington 1900, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g Yudis, Anthony J. (January 31, 1987). "Neglected Mill at Dedham Brook Revived as Condos". The Boston Globe. p. 35. ProQuest 294394528. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- ^ Gaffin, Adam (2008). "Mother Brook". Boston Online. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-03-29.

- ^ McGuire, Michael J. (March 25, 2015). "March 25, 1639: First U.S. Water Power Canal". Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ^ "INDUSTRIES: Business History of Utilities". Business History. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ^ a b "Mother Brook". The Broad Ax (First ed.). Salt Lake City, Utah. May 8, 1915. p. 2. Retrieved March 17, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "America's First Canal". The Boston Daily Globe. January 10, 1915. p. 69. Retrieved March 17, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Mother Brook Canal: Still Useful After All These Years". New England Historical Society. 25 March 2014. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- ^ Bacon, Edwin Munroe (1918). Walks and Rides in the Country Round about Boston: Covering Thirty-six Cities and Towns, Parks and Public Reservations, Within a Radius of Twelve Miles from the State House. S.J. Clarke publishing Company. p. 357.

- ^ History of Norfolk County, Massachusetts, 1622-1918. Vol. 1. S.J. Clarke publishing Company. 1918. p. 362.

- ^ Up-to-date Guide Book of Greater Boston. Murphy. 1904. p. 129.

mother brook first canal.

- ^ Nason, Elias; Jones Varney, George (1890). A Gazetteer of the State of Massachusetts: With Numerous Illustrations. Vol. 1. Heritage Books. ISBN 9780788410437.

- ^ Jobin, William R. (June 26, 1998). Sustainable Management for Dams and Water. CRC Press. p. 55. ISBN 9781574440621.

- ^ "Hohokam Canals: Prehistoric Engineering". The Arizona Experience. Archived from the original on September 14, 2012.

- ^ Maugh II, Thomas H. (24 May 2009). "Native American irrigation canals unearthed in Arizona are earliest known in Southwest". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on April 11, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Neiswander 2024, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e f g Preer, Robert (September 6, 2009). "Brook Cleanup has Local Spirit Flowing". The Boston Globe. p. South 1. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- ^ "Mother Brook Community Group". Mother Brook Community Group. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ "Mother Brook Community Group to hold annual meeting on Dec. 10 at 7 p.m. at MBACC". The Dedham Times. Vol. 32, no. 48. November 29, 2024. p. 7.

- ^ "Mother Brook Arts and Community Center". Mother Brook Arts and Community Center. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ Fox, Jeremy C. (October 8, 2012). "Staging a Comeback". The Boston Globe. p. B1. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- ^ "Harney Won At Pool". The Boston Post. January 29, 1897. p. 3. Retrieved March 17, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ McLaughlin, Jeff (May 5, 1996). "Rediscovering the Neponset River". The Boston Globe. p. South Weekly 1. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g Straight, Stephan. "Diversion of Streams to Furnish Power for Water Wheels" (PDF). Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society. 51 (1): 43–47. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 4, 2015. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- ^ a b Neiswander 2024, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d Neiswander 2024, p. 8.

- ^ a b Hanson 1976, p. 26.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Neiswander, Judy (April 17, 2020). "Tales from Mother Brook: Part 1 - Beginnings". The Dedham Times. p. 6.

- ^ Hanson 1976, p. 26-27.

- ^ a b Worthington 1900, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Phase One of Mother Brook Corridor Study completed". The Dedham Times. Vol. 28, no. 8. February 21, 2020. p. 10.

- ^ Lamson 1839, p. 56.

- ^ Neiswander 2024, p. 9, 11.

- ^ "Questions We Are Often Asked - Part II". Dedham Historical Society News-letter (July 2015): 3.

- ^ a b c d e Neiswander 2024, p. 11.

- ^ a b c Whiting, J.F. (May 27, 1915). "What People Talk About". The Boston Daily Globe. p. 10. Retrieved March 17, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Neiswander 2024, p. 9, 10.

- ^ a b c d e f Neiswander 2024, p. 10.

- ^ Neiswander 2024, p. 9-10.

- ^ a b c d Neiswander 2024, p. 3.

- ^ Worthington 1900, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Neiswander 2024.

- ^ a b c Hanson 1976, p. 31.

- ^ Worthington 1900, p. 15.

- ^ a b Informational sign placed at Mother Brook Playground at Condon Park by the Dedham Civic Pride Committee.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Worthington 1900, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d Hanson 1976, p. 53.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Neiswander 2024, p. 13.

- ^ Lamson 1839, pp. 56–7.

- ^ a b c Hanson 1976, p. 54.

- ^ Neiswander 2024, p. 13-14.

- ^ "Dedham Covenant". Ashbrook Center at Ashland University. Retrieved March 18, 2015.

- ^ Brown, Richard D.; Tager, Jack (2000). Massachusetts: A concise history. University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 1558492496.

- ^ a b c Lamson 1839, p. 57.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Neiswander 2024, p. 14.

- ^ a b Hanson 1976, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Hanson 1976, p. 55, 86.

- ^ a b c d e f Worthington 1900, p. 4.

- ^ Neiswander 2024, p. 14, 18-19.

- ^ "History of Walpole, Massachusetts, 1635−". Walpole Historical Society. Archived from the original on 2008-06-10. Retrieved 2008-04-23.

- ^ Greaves, Maude. "History of Walpole". Archived from the original on 2008-06-10. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ^ a b c Neiswander 2024, p. 16.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Worthington 1900, p. 5.

- ^ Hanson 1976, p. 102.

- ^ a b Cutter, William Richard (1910). Genealogical and Personal Memoirs Relating to the Families of the State of Massachusetts. Lewis historical Publishing Company. pp. 1875–1876. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ Dwight, Benjamin Woodbridge (1874). The History of the Descendants of John Dwight, of Dedham, Mass. J. F. Trow & son, printers and bookbinders. pp. 99–100. ISBN 978-1-981482-65-8.

- ^ Lamson 1839, p. 58.

- ^ a b c d e Neiswander 2024, p. 15.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Worthington 1900, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e f Neiswander 2024, p. 12.

- ^ a b c Neiswander 2024, p. 20.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Neiswander 2024, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Tritsch 1986, p. 13.

- ^ a b c Dedham Historical Society 2001, p. 37.

- ^ a b Worthington 1900, p. 9.

- ^ a b Worthington 1900, p. 10.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Worthington 1900, p. 11.

- ^ Wilson, Mary Jane (2006). "Benjamin Bussey, Woodland Hill, and the Creation of the Arnold Arboretum" (PDF). Arnoldia. 64 (1). Arnold Arboretum, Harvard University: 2–9. doi:10.5962/p.250991.

- ^ a b c d e f g Worthington 1900, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Neiswander, Judy (May 1, 2020). "Tales from Mother Brook: Part 3 - The Early Mills". The Dedham Times. Vol. 28, no. 18. p. 6.

- ^ Howley, Kathleen (September 5, 1998). "Boston's tiny Readville had a big role in the Civil War". The Boston Globe. p. E1. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- ^ "Emerson was a Hermit". The Boston Globe. September 1, 1895. p. 28. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ An act to incorporate certain Proprietors of Meadow-Lands (Chapter 77 of the Acts of 1797). March 3, 1798. Retrieved March 18, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Worthington 1900, p. 8.

- ^ a b c d Steinberg 2004, p. 47.

- ^ "R.O. Storrs & Co". The Inter Ocean. Chicago, Illinois. October 24, 1882. p. 1. Retrieved March 17, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Worthington 1900, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Steinberg 2004, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Worthington 1900, p. 8-9.

- ^ Worthington 1900, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Steinberg 2004, p. 48.

- ^ a b "Flood Menaces Greater Boston". The North Adams Transcript. North Adams, Massachusetts. July 26, 1938. p. 1. Retrieved March 17, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Dumanoski, Dianne (June 21, 1993). "The Charles River Low water stirs fears for future". The Boston Globe. p. 25. ProQuest 294783517. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Neiswander, Judy (May 15, 2020). "Tales from Mother Brook: Part 5 - Citizens". The Dedham Times. Vol. 28, no. 20. p. 8.

- ^ "A Capsule History of Dedham". Dedham Historical Society. 2006. Archived from the original on October 6, 2006. Retrieved 2006-11-10.

- ^ a b c d Neiswander 2024, p. 19.

- ^ Hanson 1976, p. 244.

- ^ Taylor, Jerry (May 16, 1986). "Dedham: Town Recalls its Roots Upon 250the Birthday". The Boston Globe. p. 22. ProQuest 294368862. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- ^ Kenney, Robert (May 14, 1978). "Suburbs". The Boston Globe. p. 38. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ Morgan Bolton, Michele (December 14, 2008). "Community Briefing". The Boston Globe. p. South 2. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e "Dedham's Policy is to "Sit Tight"". The Boston Globe. April 2, 1909. p. 11. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ "Water at Hyde Park Criticized". The Boston Globe. December 2, 1910. p. 1. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ "Vote Nearly Unanimous". The Boston Globe. March 24, 1911. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ Harrington, Joe (December 22, 1963). "Dedham 'Making' New Land for Building". The Boston Globe. p. A22. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ Ayers, James (July 23, 1967). "Conservationists Expect Fight Over Proposed Wetlands Bill". The Boston Globe. p. 20. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ Moore, Henry (March 24, 1968). "Rain Clouds' Silver Lining". The Boston Globe. p. 68. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ "New England News in Brief". The Boston Globe. July 18, 1975. p. 4. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ "Charles River cleaned up but oil remains in pipes". The Boston Globe. July 20, 1975. p. 6. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ "Gas Leak Fouls Mother Brook". The Boston Globe. March 30, 1990. p. 49. ProQuest 294522233. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- ^ a b Allen, Scott (May 21, 1995). "Hyde Park firm to pay $250,000 pollution fine". The Boston Globe. p. 35. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- ^ "Water". The Boston Globe. September 22, 1996. p. South Weekly 3. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- ^ a b "Adopt Your Watershed". United States Environmental Protection Agency. October 21, 2008. Retrieved October 28, 2015.

- ^ Heisler, Joe (December 8, 2002). "A Shopping Menace". The Boston Globe. p. City Weekly 4. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- ^ a b Gaffin, Adam (February 19, 2020). "Feds look at designating Neponset River from Hyde Park to Dorchester as a Superfund cleanup site". Universal Hub. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ^ Martin, E.F. (July 14, 2017). "DCR to Protect Mother Brook Diversion Point". The Dedham Times. Vol. 25, no. 28. p. 5.

- ^ "Grand Opening of Mill Pond Park" (photo). Mother Brook Community Group. July 16, 2014. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- ^ LeBlanc, Lisa (July 2, 2014). "Grand Opening of Mill Pond Park". Dedham Patch. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Parr, Jim (March 11, 2024). "A Short History of the Dedham Incinerator". Dedham Tales. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ a b c "MBACC Hosts Mother Brook Corridor Study~ January 21, 2020". Dedham Visionary Access Corporation. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ^ a b "MOTHER BROOK CORRIDOR STUDY" (pptx). Heritage Consultants. January 21, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ^ a b "Mother Brook Corridor Study". Town of Dedham. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ^ "New England Flood". The Marion Star. Marion, Ohio. February 19, 1886. p. 2. Retrieved March 17, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "The Dedham Floods". The Fitchburg Sentinel. Fitchburg, Massachusetts. February 17, 1886. p. 3. Retrieved March 17, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Jafsie Traces Kidnap Ladder". The Boston Globe. March 17, 1936. p. 1. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ "Flood Fears". Nashua Telegraph. March 23, 1948. p. 4. Retrieved March 17, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "Firemen, Crane Break Ice Jam at Dedham Dam". The Boston Globe. January 9, 1955. p. 25. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ "Flood Areas Begin Mop Uo". The Boston Globe. August 22, 1955. p. 1. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ "Hynes Offers City Aid to Flood Victims Here". The Boston Globe. August 23, 1955. p. 1. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ "Local Rivers Slacken Pace". The Boston Globe. August 25, 1955. p. 7. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ "Prorogation Rush Seems to Inspire Adroit Legislating". The Boston Globe. September 4, 1955. p. 21. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ "McCormack Asks Flood Control Study of Neponset". The Boston Globe. November 23, 1955. p. 32. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ "Neponset River Control Includes Land Saving". The Boston Globe. November 27, 1955. p. 6C. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ "Nod Given Flood Plan". The Boston Globe. September 30, 1960. p. 9. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ "Charles Nearing Crest". The Boston Globe. January 28, 1958. p. 1. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ "Areas Troubled By Overflowing Bay State Rivers". The Boston Globe. January 29, 1958. p. 1. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ a b "Town-by-Town Survey of Trouble Spots on Rising Rivers". The Boston Globe. March 21, 1968. p. 15. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ a b "N.E. Floods Cost $3,000,000". The Boston Globe. July 25, 1938. p. 1. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ "Rains Threaten Serious Floods". The Boston Globe. July 25, 1938. p. B1. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ a b c d "Flood Germs Close Beaches". The Boston Globe. July 27, 1938. p. 1. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ "Cloudbursts Added to Floods". The Boston Globe. July 28, 1938. p. 1. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ a b "Worst of Flood Past at Dedham And Needham; Rise at Newton". The Boston Globe. July 29, 1938. p. 1. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ "Three Escape Death in Capsize of Canoe". The Boston Globe. July 25, 1938. p. 1. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ "He was Micheal Ansbro". The Boston Globe. Apr 15, 1892. p. 12. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ "Mystery of Missing Bergen Show Solved: Phone Wires Crossed". The Boston Globe. April 13, 1948. p. 26. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ "Dedham Man Found Drowned". The Boston Globe. August 16, 1967. p. 33. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ "The Coburn Estate". The Boston Weekly Globe. May 11, 1881. p. 7. Retrieved March 17, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Hyde Park Boy Drowned". The Boston Globe. July 4, 1899. p. 7. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ "Boy is Drowned in Mother Brook". The Boston Globe. June 27, 1916. p. 8. Retrieved March 18, 2015.

- ^ "Child, 2, Drowns in Dedham Brook". The Boston Globe. May 21, 1927. p. 5. Retrieved March 18, 2015.

- ^ "West Roxbury Brook Dragged for Boy, 6, Missing Two Days". The Boston Globe. August 7, 1946. p. 1. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ "Boy, 14, Drowns Despite Efforts of Hyde Park Pal". The Boston Globe. July 24, 1951. p. 2. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ "4 Drowned, 2 Killed on N.E. Roads". The Boston Globe. July 19, 1959. p. 22. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ Cowen, Peter (January 27, 1972). "E. Dedham youth, 13, drowns in Hyde Park as raft capsizes". The Boston Globe. p. 3. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ "News of the Week". Newport Mercury. Newport, Rhode Island. February 2, 1895. p. 5. Retrieved March 17, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Dedham Boy Coaster Drowned Under Ice". The Boston Globe. February 15, 1929. p. 23. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Lad Saved by Human Chain". The Boston Daily Globe. December 17, 1905. p. 91. Retrieved March 17, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d Dwyer, Timothy (March 5, 1980). "A Struggle to Save Boy, 8, Under Water 20 minutes". The Boston Globe. p. 1. ProQuest 293930227. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- ^ a b "David Tundidor, 8, Hyde Park Boy Who Fell Through Ice March 4, Dies". The Boston Globe. March 22, 1980. p. 1. ProQuest 293944684. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- ^ McLaughlin, Loretta (March 6, 1980). "Deepening His Coma to Save David". The Boston Globe. p. 1. ProQuest 293932235. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- ^ "Suburban Short Notes". The Boston Post. August 14, 1875. p. 3. Retrieved March 17, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Dedham". The Boston Globe. August 29, 1878. p. 4. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ "Dives from Bridge and Rescues Boy". The Boston Globe. June 5, 1919. p. 5. Retrieved March 18, 2015.

- ^ "Swept Over Dam by Swift Current". The Boston Globe. June 6, 1925. p. 3. Retrieved March 18, 2015.

- ^ Long, Tom (February 27, 2004). "Merrill Siegan, 81, One of City's First Community Service Officers". The Boston Globe. p. C.24. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- ^ Keaney, Brian (March 18, 2009). Mother Brook rescue. myDedhamNews.com. Retrieved March 17, 2015.