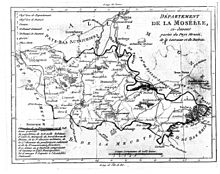

Moselle (department)

Moselle | |

|---|---|

Prefecture building of the Moselle department, in Metz | |

Location of Moselle in France | |

| Coordinates: 49°02′02″N 6°39′43″E / 49.03389°N 6.66194°E | |

| Country | France |

| Region | Grand Est |

| Treaty of Versailles | 28 June 1919 |

| Prefecture | Metz |

| Subprefectures | Forbach Sarrebourg Sarreguemines Thionville |

| Government | |

| • President of the Departmental Council | Patrick Weiten[1] (UDI) |

| Area | |

• Total | 6,216 km2 (2,400 sq mi) |

| Population (2022)[2] | |

• Total | 1,050,721 |

| • Rank | 23rd |

| • Density | 170/km2 (440/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Department number | 57 |

| Arrondissements | 5 |

| Cantons | 27 |

| Communes | 725 |

| ^1 French Land Register data, which exclude estuaries, and lakes, ponds, and glaciers larger than 1 km2 | |

| Part of a series on |

| Lorraine |

|---|

|

Moselle (French pronunciation: [mɔzɛl] ⓘ) is the most populous department in Lorraine, in the northeast of France, and is named after the river Moselle, a tributary of the Rhine, which flows through the western part of the department. It had a population of 1,046,543 in 2019.[3] Inhabitants of the department are known as Mosellans.

History

On 4 March 1790 Moselle became one of the original 83 departments created during the French Revolution.

In 1793, France annexed the enclaves of Manderen, Momerstroff, and the County of Kriechingen – all possessions of princes of the Duchy of Luxemburg – a state of the Holy Roman Empire, and incorporated them into the Moselle department. In 1795, the seigneurie de Lixing was also integrated into the Moselle department. One of its first prefects was the comte de Vaublanc, from 1805 to 1814.

By the Treaty of Paris of 1814 following the first defeat and abdication of Napoleon, France had to surrender almost all the territory it had conquered since 1792. In northeastern France, the Treaty did not restore the 1792 borders, however, but defined a new frontier to put an end to the convoluted nature of the border, with all its enclaves and exclaves. As a result, France ceded the exclave of Tholey (now in Saarland, Germany) as well as a few communes near Sierck-les-Bains (both territories until then part of the Moselle department) to Austria. On the other hand, the Treaty confirmed the French annexations of 1793, and furthermore, the south of the Napoleonic department of Sarre was ceded to France, including the town of Lebach, the city of Saarbrücken, and the rich coal basin nearby. France thus became a net beneficiary of the Treaty of Paris: all the new territories ceded to her being far larger and more strategically useful than the few territories ceded to Austria. All these new territories were incorporated into the Moselle department, and giving Moselle a larger area than it had had since 1790.

However, with the return of Napoleon (March 1815) and his final defeat at the Battle of Waterloo (June 1815), the Treaty of Paris in November 1815 imposed much harsher conditions on France. Tholey and the communes around Sierck-les-Bains were still to be ceded as agreed in 1814, but the south of the Sarre department with Saarbrücken was withdrawn from France. In addition, France had to cede to Austria the area of Rehlingen (now in Saarland) as well as the strategic fort-town of Saarlouis and the territory around it, all territories and towns which France had controlled since the 17th century, and which had formed part of the Moselle department since 1790. At the end of 1815, Austria transferred all these territories to Prussia, making for the first time a shared border for those two states.

Thus, by the end of 1815, the Moselle department finally had the limits that it would keep until 1871. It was slightly smaller than at its creation in 1790, the incorporation of the Austrian enclaves not compensating for the loss of Saarlouis, Rehlingen, Tholey, and the communes around Sierck-les-Bains. Between 1815 and 1871, the department had an area of 5,387 km2 (2,080 sq mi). Its prefecture (capital) was Metz. It had four arrondissements: Metz, Briey, Sarreguemines, and Thionville.

After the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, almost all of the Moselle department, along with Alsace and portions of the Meurthe and Vosges departments, went to the German Empire by the Treaty of Frankfurt on the grounds that most of the population in those areas spoke German dialects. Bismarck omitted only one-fifth of Moselle (the arrondissement of Briey in the extreme west of the department) from annexation, (Bismarck later regretted his decision when it was discovered that the region of Briey and Longwy had rich iron-ore deposits.) The Moselle department ceased to exist on 18 May 1871, and the eastern four-fifths of Moselle was annexed to Germany merged with the also German-annexed eastern third of the Meurthe Department into the German Department of Lorraine, based in Metz, within the newly established Imperial State of Alsace-Lorraine. France merged the remaining area of Briey with the truncated Meurthe department to create the new Meurthe-et-Moselle department (a new name chosen on purpose to remind people of the lost Moselle department) with its préfecture at Nancy.

In 1919, following the French victory in the First World War, Germany returned Alsace-Lorraine to France under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles. However, it was decided not to recreate the old separate departments of Meurthe and Moselle by reverting to the old department borders of before 1871. Instead, Meurthe-et-Moselle was left untouched, and the annexed part of Lorraine (Bezirk Lothringen) was reconstituted as the new department of Moselle. Thus, the Moselle department was reborn, but with quite different borders from those before 1871. Having lost the area of Briey, it had now gained the areas of Château-Salins and Sarrebourg which before 1871 had formed one-third of the Meurthe department and which had been part of the Reichsland of Alsace-Lorraine since 1871.

The new Moselle department now reached its current area of 6,216 km2 (2,400 sq mi), larger than the old Moselle because the areas of Château-Salins and Sarrebourg were far larger than the area of Briey and Longwy.

When the Second World War was declared on 3 September 1939, around 30% of Moselle's territory lay between the Maginot Line and the German frontier.[4] 302,732 people, around 45% of the department's population, were evacuated to departments in central and western France during September 1939. Of those evacuated, around 200,000 returned after the war.[4]

In spite of the 22 June 1940 armistice, Moselle was again annexed by Germany in July of that year by becoming part of the Gau Westmark. Adolf Hitler considered Moselle and Alsace parts of Germany, and as a result the inhabitants were drafted into the German Wehrmacht.

Several organized groups were formed in resistance to the German occupation, notably the Groupe Mario, led by Jean Burger, and the Groupe Derhan. During these years more than 10,000 Mosellans were deported to camps, many to the Sudetenland, for publicly opposing the annexation.[5]

The United States Army liberated Moselle from Nazi Germany in the Battle of Metz in September 1944, although combat continued in the northeastern part of the department until March 1945. Moselle was returned to French governance in 1945 with the same frontiers as in 1919.

The department was hit particularly hard during the war: the American bombardments in the spring of 1944 caused widespread collateral damage; 23% of the communes in Moselle were 50% destroyed, and 8% of the communes were than 75% destroyed.[6]

As a result of German aggression during the war, the French Government actively discouraged the German heritage of the region, and the local German Lorraine Franconian dialects ceased to be used in the public realm. In recent years there has been a revival of the old dialects and distinct Franco-German culture of the region with the onset of open borders between France and Germany as members of the European Union's Schengen Treaty.

Geography

Moselle is part of the current region of Grand Est and is surrounded by the French departments of Meurthe-et-Moselle and Bas-Rhin, as well as Germany (states of Saarland and Rhineland-Palatinate) and Luxembourg in the north. Parts of Moselle belong to Parc naturel régional de Lorraine.

The following are the most important rivers:

The department is geographically organized around the Moselle valley. The region was long considered a march between Alsace and the north, remaining relatively poor until the 19th century, and was consequently less urbanized and populous than other regions at the time.

Environment

The environment has undergone heavy industrialization linked to iron deposits in Lorraine, which have artificialized valleys and river banks. Industries have created vast land holdings in the valleys by buying land from agriculturists and profiting from water rights.

Questions of environmental degradation were politicized at the end of the 19th century. Since then, one academic has argued that a consensus has been reached in the region regarding pollution, which is seen as the price of continuing the steel industry.[7]

Principal towns

The most populous commune is Metz, the prefecture. As of 2019, there are 8 communes with more than 15,000 inhabitants:[3]

| Commune | Population (2019) |

|---|---|

| Metz | 118,489 |

| Thionville | 40,778 |

| Montigny-lès-Metz | 21,879 |

| Forbach | 21,597 |

| Sarreguemines | 20,635 |

| Yutz | 17,143 |

| Hayange | 16,005 |

| Saint-Avold | 15,415 |

Economy

In the 19th century, Moselle's economy was characterized by heavy industry, especially steel and iron works. After the weakening of these industries at the end of the 20th century, the department has tried to promote new economic activities based on industry and technology, such as the Cattenom Nuclear Power Plant.

The Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Moselle created the "Achat-Moselle" website in the 2000s to address issues of e-commerce and in-person commerce. The site helps local businesses to create pages showcasing their services, boosting their visibility and potential activity.[8]

Demographics

The inhabitants of the department are called Mosellans in French.

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Figures before 1872 are for the old department of Moselle. Sources:[9][10] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The population has remained relatively stable since World War II and now exceeds 1 million, located mostly in the urban area around Metz and along the river Moselle.

If the Moselle department still existed in its limits of between 1815 and 1871, its population at the 1999 French census would have been 1,089,804 inhabitants. The current Moselle department, whose limits were set in 1919, had less population, with only 1,023,447 inhabitants. This is because the industrial area of Briey and Longwy lost in 1871 is more populated than the rural areas of Château-Salins and Sarrebourg gained in 1919. The southern part of the department, especially around Saulnois, has remained more rural.

A significant minority of inhabitants of the department (fewer than 100,000) speak a German dialect known as platt lorrain or Lothringer Platt (see Lorraine Franconian and Linguistic boundary of Moselle). The German dialect is found primarily in the northeast section of the department, which borders Alsace, Luxembourg, and Germany. Four sites in Moselle were included in the Atlas Linguarum Europae, to investigate the Germanic dialects used in these areas: Arzviller, Guessling, Petit-Réderching and Rodemack.[11]

Linguistically, Platt can be further subdivided into three varieties, going from east to west: Rhenish Franconian, Moselle Franconian, and Luxembourgish.

Politics

The president of the Departmental Council is Patrick Weiten, elected in 2011.

Presidential elections 2nd round

| Election | Winning Candidate | Party | % | 2nd Place Candidate | Party | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | Emmanuel Macron | LREM | 50.46 | Marine Le Pen | FN | 49.54 | |

| 2017[12] | Emmanuel Macron | LREM | 57.66 | Marine Le Pen | FN | 42.34 | |

| 2012 | Nicolas Sarkozy | UMP | 53.50 | François Hollande | PS | 46.50 | |

| 2007 | Nicolas Sarkozy | UMP | 56.56 | Ségolène Royal | PS | 43.44 | |

| 2002[12] | Jacques Chirac | RPR | 78.11 | Jean-Marie Le Pen | FN | 21.89 | |

| 1995[13] | Jacques Chirac | RPR | 51.30 | Lionel Jospin | PS | 48.70 | |

Current National Assembly Representatives

Culture

Eastern Moselle has preserved a number of local traditions, notably the Kirb festivals celebrated in October in rural areas, Mardi Gras parades in Sarreguemines, and the August mirabelle festival in Metz which includes a variety of cultural activities.

The Opéra-Théâtre de Metz, is the oldest active theater in France and has continuously operated from the 18th century. Metz also has a number of concert halls that offer diverse events such as comedy shows and symphony orchestras.

Thionville is home to the NEST (Nord-Est Théâtre).

Law

Moselle and Alsace to its east have their own laws in certain fields. The statutes in question date primarily from the period 1871–1919 when the area was part of the German Empire. With the return of Alsace-Lorraine to France in 1919, many in central government assumed that the recovered territories would be subject to French law.

Local resistance to a total acceptance of French law arose because some of Bismarck's reforms included strong protections for civil and social rights. After much discussion and uncertainty, Paris accepted in 1924 that pre-existing German law would apply in certain fields, notably hunting, economic life, local government relationships, health insurance, and social rights. Many of the relevant statues continue to be referred to in the original German, as they have never been formally translated.

One major difference with French law is the absence of the formal separation between church and state: several mainstream denominations of the Christian church as well as the Jewish faith[15] benefit from state funding, despite principles applied rigorously in the rest of France.

Tourism

Over the past twenty years the Conseil départemental de la Moselle has encouraged the development of tourism in the department. The creation of more hotels, camp sites, hiking trails, bicycle paths, and other tourist services have significantly increased the number of tourists in Moselle.

The Conseil départemental de la Moselle created an "Organ Trail" to display a number of the department's 650 organs, many of which were built in the area and have historic significance. The oldest organ in the department dates is in the cathedral Saint-Étienne de Metz and dates from 1537. In the 19th century, Moselle had 17 operational organ factories, although only five exist in the present day.

Moselle has numerous chateaux, manors, and fortified manors, dating largely from the 17th and 18th centuries, many of which are partially destroyed.

- Statue of Abraham de Fabert, in Metz

- Rodemack, one of the most beautiful villages of France

- Citadel of Bitche

- Medieval heritage site of Hombourg-Haut

See also

- Arrondissements of the Moselle department

- Cantons of the Moselle department

- Communes of the Moselle department

- German exonyms (Moselle)

References

- ^ "Répertoire national des élus: les conseillers départementaux". data.gouv.fr, Plateforme ouverte des données publiques françaises (in French). 4 May 2022.

- ^ "Populations de référence 2022" (in French). The National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies. 19 December 2024.

- ^ a b Populations légales 2019: 57 Moselle, INSEE

- ^ a b Le Marrec, Bernard, Gérard (1990). Les années noires, la Moselle annexée par Hitler. Éditions Serpenoises. p. 133. ISBN 2-87692-062-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Alfred Wahl (direction), "Les résistances des Alsaciens-Mosellans durant la Seconde Guerre mondiale (1939-1945)", Metz, Centre régional universitaire lorrain d’histoire, 2006, compte-rendu du colloque organisé les 19 et 20 novembre 2004 à Strasbourg par les Universités de Metz et de Strasbourg et la Fondation entente franco-allemande

- ^ "Bilan", in 1944-1945, Les années Liberté, Le Républicain Lorrain, Metz, 1994 (p. 54)

- ^ Garcier, Roman. ""La pollution industrielle de la Moselle française. Naissance, développement et gestion d'un problème environnemental, 1850-2000"". Thesis.

- ^ "Magasins et commerces de Moselle - Achat Moselle". www.achat-moselle.com.

- ^ "Historique de la Moselle". Le SPLAF.

- ^ "Évolution et structure de la population en 2016". INSEE.

- ^ Eder, Birgit (2003). Ausgewählte Verwandtschaftsbezeichnungen in den Sprachen Europas. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. p. 299. ISBN 3631528736.

- ^ a b l'Intérieur, Ministère de. "Présidentielles". interieur.gouv.fr/Elections/Les-resultats/Presidentielles.

- ^ "Résultats de l'élection présidentielle de 1995 par département - Politiquemania". www.politiquemania.com.

- ^ Nationale, Assemblée. "Assemblée nationale ~ Les députés, le vote de la loi, le Parlement français". Assemblée nationale.

- ^ In Moselle these are the Diocese of Metz, the CIM, the EPCAAL and the EPRAL.

Further reading

- Carrol, Alison. The Return of Alsace to France, 1918-1939 (Oxford University Press, 2018).

- Zanoun, Louisa. "Language, Regional Identity and the Failure of the Left in the Moselle Département, 1871-1936." European History Quarterly 41.2 (2011): 231–254.

- Zanoun, Louisa. "Interwar politics in a French border region: the Moselle in the period of the Popular Front, 1934-1938." (PhD Diss. The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), 2009) online.

External links

- (in French) Prefecture website

- (in French) Departmental Council website

- (in French) Moselle-annuaire.fr, Moselle's Websites Directory