Monument to the Fighters of the Revolution

The Monument to the Fighters of the Revolution (Russian: Памятник Борцам Революции) is a memorial on the Field of Mars in Saint Petersburg. It marks the burial places of some of those who died during the February and October Revolutions in 1917, and casualties who died between 1917 and 1933 in the Russian Civil War or otherwise in the establishment of Soviet power. It contains the first eternal flame in Russia.

The Field of Mars was selected by the Petrograd Soviet as the site for the ceremonial burials of those who had died during the February Revolution, which had toppled the tsarist autocracy. 184 bodies were interred in communal graves at the centre of the field, and a competition was announced for the design of a monument to those buried there. The competition was won by architect Lev Rudnev and consisted of granite walls forming the corners of a square enclosing a central space. Other prominent figures in the early Soviet government, and those who had died fighting to establish Soviet power, were buried on the site, as were those who died during the October Revolution. The monument, and the Field of Mars in general, became a pantheon to those who had died in the service of the state. Large granite tablets at the end of each wall carried epitaphs by People's Commissar of Education Anatoly Lunacharsky, extolling the virtues and sacrifices of those buried there. The Field of Mars was for a time renamed the "Victims of Revolution Square", and was sometimes called "The Square of the Graves of the Victims of the Revolution".

Burials ceased after 1933, though the monument continued to be developed. Used for vegetable gardens and the site of artillery batteries during the siege of Leningrad, the name "Field of Mars" was restored in 1944, and the square was repaired after the war. The central space of the memorial, which had been covered with a circular lawn and floral displays, was replaced with a paved square in the late 1950s, with the first eternal flame in Russia at the centre, lit in 1957. The flame has been used as the source of eternal flames elsewhere in the city and in Russia, including the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier near the Moscow Kremlin Wall.

Location and design

Since the founding of the city, the space occupied by the Field of Mars had been at times the site of parks, pleasure gardens, festivities, and military parades.[1] The monument occupies the centre of the field and consists of four L-shaped walls of grey granite enclosing a central square.[2] The enclosed square contains the communal graves of some of those who died during the February and October Revolutions. Additional graves are around the enclosed area, marked by 12 plaques listing the names of the prominent Soviet figures buried there. The middle of the space is marked with a paved surface, with an eternal flame in the centre.[2]

Revolutionary burials

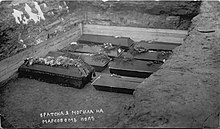

After the February Revolution, the Petrograd Soviet decided to create an honorary communal burial ground for those who had been killed in the unrest. The option of interment in an existing cemetery was rejected, with the argument that the burial site had to be "important, eloquent, a place of pilgrimage within the city centre."[3] Various locations were proposed: Kazan and Palace Squares, the Summer and Tauride Gardens, and the Field of Mars.[1] The Soviet initially selected Palace Square as the location for the graves but changed this to the Field of Mars after representations from prominent artists, including Maxim Gorky.[2][3][4] An important consideration was the plan to site the putative Constituent Assembly on the Field of Mars, which would then overlook a monument to those who had died in the revolution.[1] Architects Yevgeny-Karl Schröter, Lev Rudnev, Sigizmund Dombrovsky, and A. L. Shilovsky oversaw the preparations of four large L-shaped communal graves in the centre of the Field of Mars.[1]

The burials were scheduled to take place on 5 April [O.S. 23 March] 1917, but prior to this news circulated that there would not be any funeral rites.[4] Relatives of the dead hurried to claim and bury them in other cemeteries with the traditional rites.[1] The accepted death toll of the 'victims of February' was 1,382, of whom 869 were soldiers who had mutinied, and 237 were workers.[3] Ultimately only 184 victims were buried on the Field of Mars, comprising 86 soldiers, 9 sailors, 2 officers, 32 workers, 6 women, 23 people for whom social status could not be determined, and 26 unknown dead.[1] The city soviet declared 5 April a day off work, and nearly a million citizens turned out to join the funeral processions, which carried the dead from the hospitals and chapels across the city, accompanied by the singing of La Marseillaise and the revolutionary hymn You Fell Victim to a Fateful Struggle.[3][5] The graves had been prepared by blasting trenches in the frozen ground, with the lowering of each coffin marked by a cannon shot from the Peter and Paul Fortress.[4] By one estimate some 800,000 people attended the funerals.[1][4] No clergy were allowed to officiate or participate in the ceremonies. Historian Richard Stites remarks that the funerals were the "first secular outdoor ceremony in Russian history, the first major non-oppositional and all-class ceremony in the lifetime of the Provisional Government, and the only one also without a central charismatic figure as a focus."[5] Nevertheless, when some of the coffins, which had been draped in red material, were uncovered for burial, they found to be inlaid with Orthodox crosses.[3] Following the funerals the Bolshevik newspaper Pravda carried pieces by leading party members Lev Kamenev and Alexandra Kollontai calling for the response to the deaths to be the securing and building of new freedoms in a democratic Russia.[3]

Creation of the memorial

A competition for the design of the memorial was opened almost immediately after the funerals had taken place.[6] A commission was set up to judge the entries, consisting of prominent architects, artists and writers, including: Ivan Fomin, Alexandre Benois, Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, Mstislav Dobuzhinsky, Ivan Bilibin, Alexander Blok, Maxim Gorky, and Anatoly Lunacharsky.[4][7] Eleven designs were submitted. One envisaged a huge tetrahedral metal pyramid with a female figure at the top, symbolising the freedom of the Russian people. Another proposed the creation of a giant cube, angled on inverted truncated pyramids, while yet another version was for a high four-tiered tower with rooms built into it. Variations on creating a 32-meter-high (105 ft) column along the lines of Auguste de Montferrand's Alexander Column were also presented.[7] The commission rejected most of the entrants on the grounds of being disproportionate to the scale of the location and likely to distort the city's historical appearance.[7] The design selected was that put forward by Lev Rudnev, to the "Fighters of the Revolution".[2][4][6] Modest in comparison to some of the proposals, it had the advantage at a time of straitened finances of re-using materials from the Salniy Buyan, a collection of storage yards and warehouses along the river Pryazhka, which had been dismantled before the war as part of the expansion of the neighbouring shipyard.[7][8] Large granite blocks were thus readily available. The monument to the "Fighters of the Revolution" was opened on 7 November 1919.[2] It consisted of four large L-shaped granite walls enclosing an open space at the centre of the Field of Mars. Epitaphs by Anatoly Lunacharsky, People's Commissar of Education, were inscribed on eight large tablets placed at the end of each wall.[1][4][2][6] The design of the inscriptions was carried out by artists Vladimir Konashevich and Nikolai Tyrsa, with the construction of the monument overseen by Lev Ilyin.[2][4]

Soviet pantheon

The burials of the dead of the February Revolution started a trend for the Field of Mars to become a pantheon of those who died in the service of the revolution and the achievement of Soviet power.[2] The first individual burial, that of V. Volodarsky, took place on 23 June 1918. Volodarsky, a member of the Presidium of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee, had been assassinated three days earlier.[1] Other interments that year included Moisei Uritsky, chairman of the Petrograd Cheka who was assassinated in August 1918, and Semyon Nakhimson, who was killed in the Yaroslavl Uprising in July 1918.[1][9] Further burials took place later that year, when a number of the dead of the October Revolution were interred.[1] On the first anniversary of the October Revolution the Field of Mars was renamed the "Victims of Revolution Square" and was sometimes called "The Square of the Graves of the Victims of the Revolution."[1][4] Individual burials continued over the next few years, with the Civil War commander A. S. Rakov in 1919 and All-Russian Central Executive Committee member Semyon Voskov in 1920.[1][4] Other communal interments were the eight members of the Finnish Communist Party killed in the Kuusinen Club Incident in 1920, seven officers of the 3rd Petrograd Rifle Regiment killed when the regiment defected in 1919, and four members of the Latvian Riflemen killed during the Yaroslavl rising in 1920.[10][11][12]

The layout of the square was further developed following the installation of the monument, with gardens and pathways to the design of Ivan Fomin.[1] The redesign was completed in 1921, and on 25 October the square was transferred to the city's Garden and Park Administration. In 1922 the Comintern and the All-Russian Central Executive Committee proposed creating a monument to the October Revolution, but the project was never carried out.[1] The last burial on the square, that of the secretary of the Leningrad city committee of the CPSU Ivan Gaza, took place on 8 October 1933.[1][4] The graves are marked with granite plaques, some with a single name, others with multiple names. Another plaque states "Here are buried those who died in the days of the February Revolution and the leaders of the Great October Socialist Revolution who fell in battles during the Civil War".[4]

Postwar

The square was laid out with vegetable gardens during summer 1942 to help feed the city during the siege of Leningrad, and also hosted an artillery battery.[13] The square's former name, the Field of Mars, was restored on 13 January 1944.[1] It underwent further reconstruction between 1947 and 1955, and in 1957 a new design for the central area of the memorial by Solomon Maiofis resulted in a paved square with an eternal flame lit on 6 November 1957, in memory of the victims of various wars and revolutions.[1][2][4][13] The flame, lit from the open-hearth furnace of the Kirov Factory, was the first eternal flame in Russia.[1][4] The flame from the Field of Mars was also used to light the eternal flame at the Piskaryovskoye Memorial Cemetery on 9 May 1960, and at other memorials in Saint Petersburg.[1] The flame was delivered to Moscow in 1967 and on 8 May it was used to light the eternal flame on the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier near the Kremlin Wall.[1][4]

The square was once more reconstructed between 1998 and 2001. Over 3,800 new bushes and trees were planted, and the paths and lawns were repaired. The monument to the "Fighters of the Revolution" was also restored, being relit on 14 November 2003 with a flame once again taken from the Kirov Factory's furnace.[1] By the early 2000s, with parking and transport around the city becoming problematic, proposals have occasionally been made to build a car park under the Field of Mars. The presence of graves has led residents to oppose these plans.[1] By April 2014 the names on the granite slabs were becoming indistinct. Experts from the State Museum of Urban Sculpture carried out maintenance involving the preventative washing of the granite walls and plaques, and repairing the text of the inscriptions.[2]

Named burials

| Image | Name | Born | Died | Occupation | Monument | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Dmitriy Avrov | 1890 | 1922 | Revolutionary, military leader in the Russian Civil War. Member of the presidium of the army executive committee and the Commissioner of the 1st Army of the Northern Front, Commander of the Petrograd Military District, Commander of the 7th Army. |  |

[14] |

| Indrikis Daibus | 1920 | Member of the Latvian Riflemen. Killed in the Yaroslavl Uprising. |  |

[10] | ||

| Dorofeyev | 1919 | Battalion commissar of the 3rd Petrograd Rifle Regiment. Killed by White forces in the regiment mutiny on 29 May 1919. |  |

[11] | ||

| Viktor Gagrin | 1892 | 1919 | Commander of a regiment of the Bashkir division in the Russian Civil War. Killed in action. |  |

[15] | |

| Ivan Gaza | 1894 | 1933 | Political and military leader. Deputy of the Petrograd Soviet. Fought on armoured trains during the Russian Civil War. Party member of the Kirov Plant. Secretary of the Moscow-Narva District Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. |  |

[16] | |

| Nikandr Grigoriev | 1890 | 1919 | Printhouse worker. Head of the 1st partisan detachment of printers, fought against Finnish counterrevolutionaries in the Russian Civil War. Commissioner of the 2nd Infantry Division of the 7th Army. Killed in battle against Nikolai Yudenich's forces. |  |

[15] | |

|

Tuomas W. Hyrskymurto | 1881 | 1920 | Finnish Communist, organizer of the Finnish Communist Party. Killed in the Kuusinen Club Incident. |  |

[12] |

| Väinö E. Jokinen | 1879 | 1920 | Finnish Communist, journalist, member of the Parliament of Finland for the Social Democratic Party of Finland. Secretary of the Finnish People's Delegation, of the Finnish Socialist Workers' Republic during the Finnish Civil War. Killed in the Kuusinen Club Incident. |  |

[12] | |

| Kalinin | 1919 | Battalion commissar of the 3rd Petrograd Rifle Regiment. Killed by White forces in the regiment mutiny on 29 May 1919. |  |

[11] | ||

| Ferdinand T. Kettunen | 1889 | 1920 | Finnish Communist, member of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, steward of the Finnish Communist Party's military organization. Killed in the Kuusinen Club Incident. |  |

[12] | |

| Ivan Kotlyakov | 1885 | 1929 | A founder of the Kursk branch of the Russian Social-Democratic Labor Party. Party organizer, member of the City Duma, deputy of mayor Mikhail Kalinin. Member of Petrograd Council and Provincial Executive Committee, head of the Council of the National Economy of the Northern Region, head of the Leningrad Regional and City Finance Department. |  |

[17] | |

| Aleksandr Kupshe | 1887 | 1919 | Commissar of the 3rd Petrograd Rifle Regiment. Killed by White forces in the regiment mutiny on 29 May 1919. |  |

[11][18] | |

|

Mikhail Lashevich | 1884 | 1928 | Soviet military and party leader, member of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, later Bolshevik. Red Army commander during the Russian Civil War, member of the Revolutionary Military Council, Deputy Commissar for War. |  |

[17] |

| Karl Liepin | 1920 | Member of the Latvian Riflemen. Killed in the Yaroslavl Uprising. |  |

[10] | ||

| Vladimir Likhtenshtadt | 1882 | 1919 | Russian revolutionary (SR-maximalist, Menshevik, then communist), translator. Commissar of the 6th Division headquarters of the 7th Army. Captured and shot by White forces. |  |

[15] | |

| Konsta Lindqvist | 1877 | 1920 | Finnish Communist, member of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, member of the Finnish Communist Party's military organization and industrial committee. Killed in the Kuusinen Club Incident. |  |

[12] | |

| Kotya Mgebrov-Chekan | 1913 | 1922 | Child actor and agitator. Read revolutionary poems and performed in plays of Proletkult. Killed in a tram accident. |  |

[19] | |

| Lev Mikhailov | 1872 | 1928 | Bolshevik, used the pseudonym "Politicus", chairman of the first legal Petersburg Committee of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, member of the presidium of the Petrograd Provincial Executive Committee, diplomatic representative to various countries and regions, Executive Secretary of the All-Union Society of the Old Bolsheviks, delegate to party congresses. |  |

[17] | |

| Semyon Nakhimson | 1885 | 1918 | Latvian revolutionary, member of the Social Democratic Organization of Latvia. Member of the Petrograd Committee of the Russian Social-Democratic Labor Party (Bolsheviks), member of the Central Executive Committee of the Petrograd Soviet, member of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee. Military commissar of the Yaroslavl Military District. Killed in the Yaroslavl Uprising. |  |

[20] | |

| Pekar | 1919 | Communist. Killed by White forces in the mutiny on 29 May 1919. |  |

[11] | ||

| Emil Peterson | 1920 | Member of the Latvian Riflemen. Killed in the Yaroslavl Uprising. |  |

[10] | ||

|

Jukka Rahja | 1887 | 1920 | Finnish Communist, member of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, member of the Finnish Communist Party. Killed in the Kuusinen Club Incident. |  |

[12] |

| Aleksandr Rakov | 1919 | Head of the Vyborg Military Revolutionary Committee, Commissioner of the 2nd Petrograd Brigade. Killed by White forces in the regiment mutiny on 29 May 1919. |  |

[11] | ||

| Jussi Sainio | 1880 | 1920 | Finnish Communist, trade union organiser and politician. Member of the Finnish Communist Party. Killed in the Kuusinen Club Incident. |  |

[12] | |

| Liisa Savolainen | 1897 | 1920 | Finnish Communist, a founder of the Finnish Communist Party. Killed in the Kuusinen Club Incident. |  |

[12] | |

| Sergeyev | 1919 | Battalion commissar of the 3rd Petrograd Rifle Regiment. Killed by White forces in the regiment mutiny on 29 May 1919. |  |

[11] | ||

| Rudolf Sivers | 1892 | 1918 | Bolshevik, Red Army commander in the Russian Civil War. Fought in South Russia, commanded the 1st Special Ukrainian Brigade as part of the 9th Army. Mortally wounded in battle. |  |

[21] | |

| Pyotr Solodukhin | 1892 | 1920 | Bolshevik, Red Army commander in the Russian Civil War. Delegate to the Petrograd Soviet. Fought in South Russia, killed in battle. |  |

[20] | |

| Pavel Tavrin | 1919 | Commander of the 3rd Petrograd Rifle Regiment. Killed by White forces in the regiment mutiny on 29 May 1919. |  |

[11] | ||

|

Nikolay Tolmachyov | 1895 | 1919 | Bolshevik, Red Army commissar during the Russian Civil War. Member of the Ural regional party committee, chief political commissar of the 3rd Army, organizer of the first political departments of the Red Army. Died during battles with the White forces. |  |

[22] |

|

Grigori Tsiperovich | 1871 | 1932 | Bolshevik economist and trade unionist. Alternate member of the Executive Committee of the Communist International, Petrograd Economic Council, Commissariat for Foreign Affairs. |  |

[23] |

|

Moisei Uritsky | 1873 | 1918 | Member of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, later Menshevik, Mezhraiontsy group, Bolshevik from 1917. Chief of the Petrograd Cheka, member of the Central Committee. Assassinated by Leonid Kannegisser in 1918. |  |

[24] |

| Juho Viitasaari | 1891 | 1920 | Finnish Communist, a founder of the Finnish Communist Party, Red Guards officer. Killed in the Kuusinen Club Incident. |  |

[12] | |

|

V. Volodarsky | 1891 | 1918 | Member of the Mezhraiontsy group, elected to the Petrograd City Duma. Public speaker and agitator. Member of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee. Assassinated in 1918 by Grigory Ivanovich Semyonov. |  |

[25] |

|

Semyon Voskov | 1888 | 1920 | Member of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party. Food Commissioner of the Union of Communes of the Northern Region, served in the Russian Civil War. Commissar of the 9th rifle division. |  |

[26] |

|

Konstantin Yeremeyev | 1874 | 1931 | Revolutionary, Soviet party and military leader, journalist. Commander of the Voronezh fortified area. Co-founder and deputy head of the State Publishing House, first editor of Krokodil. Member of the Revolutionary Military Council of the Baltic Fleet, member of the Revolutionary Military Council of the USSR, head of the Political Directorate of the Baltic Fleet. |  |

[27] |

| Yulii Zostyn | 1920 | Member of the Latvian Riflemen. Killed in the Yaroslavl Uprising. |  |

[10] |

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w "Марсово поле". walkspb.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 30 June 2019. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Памятник "Борцам революции" на Марсовом поле" (in Russian). State Museum of Urban Sculpture. Archived from the original on 30 December 2018. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Merridale, Catherine (2001). Night of Stone: Death and Memory in Russia. London: Granta Books. pp. 119–121. ISBN 1-86207-452-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Борцам революции, памятник". encspb.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ a b Stites, Richard (1989). Revolutionary Dreams: Utopian Vision and Experimental Life in the Russian Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 81–82. ISBN 9-780195-055375.

- ^ a b c "В ознаменование великого переворота, преобразившего Россию. Часть 2" (in Russian). Правительство Санкт-Петербурга: Комитет по государственному контролю, использованию и охране памятников истории и культуры. Archived from the original on 28 February 2019. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ a b c d "Памятник Борцам Революции". walkspb.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 30 June 2019. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ "Царицын луг - Марсово поле". citywalls.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ Merridale, Catherine (2001). Night of Stone: Death and Memory in Russia. London: Granta Books. p. 182. ISBN 1-86207-452-6.

- ^ a b c d e Drozdova, Nadezhda (29 January 2018). "Кто похоронен на Марсовом поле? Латышские стрелки" (in Russian). Nevskie Novosti. Archived from the original on 6 July 2018. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Drozdova, Nadezhda (7 November 2017). "Кто похоронен на Марсовом поле? Александр Раков, Павел Таврин, Пекар, Дорофеев, Калинин, Сергеев" (in Russian). Nevskie Novosti. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Drozdova, Nadezhda (6 April 2019). "Кто похоронен на Марсовом поле? Раскол финских коммунистов" (in Russian). Nevskie Novosti. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ a b "Field of Mars". SaintPetersburg.com. Archived from the original on 2019-06-08. Retrieved 2019-06-28.

- ^ Drozdova, Nadezhda (28 October 2018). "Кто похоронен на Марсовом поле? Дмитрий Авров" (in Russian). Nevskie Novosti. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ a b c Drozdova, Nadezhda (28 August 2017). "Кто похоронен на Марсовом поле? К столетию Великой Октябрьской революции" (in Russian). Nevskie Novosti. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ Drozdova, Nadezhda (2 February 2018). "Кто похоронен на Марсовом поле? Иван Газа" (in Russian). Nevskie Novosti. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ a b c Drozdova, Nadezhda (11 September 2017). "Кто похоронен на Марсовом поле? Лев Михайлов, Михаил Лашевич и Иван Котляков" (in Russian). Nevskie Novosti. Archived from the original on 15 January 2019. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ Drozdova, Nadezhda (18 October 2017). "Кто похоронен на Марсовом поле? "Александр Купше был товарищем моего отца"" (in Russian). Nevskie Novosti. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ Drozdova, Nadezhda (13 June 2018). "Кто похоронен на Марсовом поле? Артист-агитатор Котя Мгебров-Чекан" (in Russian). Nevskie Novosti. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ a b Drozdova, Nadezhda (4 September 2017). "Кто похоронен на Марсовом поле? Семён Нахимсон и Пётр Солодухин" (in Russian). Nevskie Novosti. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ Drozdova, Nadezhda (23 November 2017). "Кто похоронен на Марсовом поле? Рудольф Сиверс" (in Russian). Nevskie Novosti. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ Drozdova, Nadezhda (4 December 2017). "Кто похоронен на Марсовом поле? Николай Толмачёв" (in Russian). Nevskie Novosti. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ Drozdova, Nadezhda (27 April 2018). "Кто похоронен на Марсовом поле? Григорий Цыперович" (in Russian). Nevskie Novosti. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ Drozdova, Nadezhda (6 March 2017). "Кто похоронен на Марсовом поле? Моисей Урицкий" (in Russian). Nevskie Novosti. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ Drozdova, Nadezhda (7 November 2018). "Кто похоронен на Марсовом поле? В. Володарский-Гольдштейн" (in Russian). Nevskie Novosti. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ Drozdova, Nadezhda (29 December 2018). "Кто похоронен на Марсовом поле? Семён Восков" (in Russian). Nevskie Novosti. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ Drozdova, Nadezhda (5 September 2018). "Кто похоронен на Марсовом поле? Константин Еремеев" (in Russian). Nevskie Novosti. Retrieved 18 June 2019.