Monmouthshire and Brecon Canal

The Monmouthshire and Brecon Canal (Welsh: Camlas Sir Fynwy a Brycheiniog) is a small network of canals in South Wales. For most of its currently (2018) navigable 35-mile (56 km) length[1] it runs through the Brecon Beacons National Park, and its present rural character and tranquillity belies its original purpose as an industrial corridor for coal and iron, which were brought to the canal by a network of tramways and/or railroads, many of which were built and owned by the canal company.

The "Mon and Brec" was originally two independent canals – the Monmouthshire Canal from Newport to Pontymoile Basin (including the Crumlin Arm) and the Brecknock and Abergavenny Canal running from Pontymoile to Brecon. Both canals were abandoned in 1962, but the Brecknock and Abergavenny route and a small section of the Monmouthshire route have been reopened since 1970. Much of the rest of the original Monmouthshire Canal is the subject of a restoration plan, which includes the construction of a new marina at the Newport end of the canal.

The Monmouthshire Canal

| Monmouthshire Canal Navigation Act 1792 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Long title | An Act for making and maintaining a Navigable Cut or Canal from or from some Place near Pontnewynydd into the River Usk, at or near the Town of Newport, and a Collateral Cut or Canal from the same, at or near a Place called Cryndau Farm, to or near to Crumlin Bridge, all in the County of Monmouth; and for making and maintaining Railways or Stone Roads, from such Cuts or Canals to several Iron Works and Mines in the Counties of Monmouth and Brecknock. |

| Citation | 32 Geo. 3. c. 102 |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 11 June 1792 |

This canal was authorised by an act of Parliament, the Monmouthshire Canal Navigation Act 1792 (32 Geo. 3. c. 102), passed on 11 June 1792, which created the Company of Proprietors of the Monmouthshire Canal Navigation and empowered it to raise £120,000 by the issuing of shares, and a further £60,000 if required. The act stated that the canal would run from Pontnewynydd to the River Usk near Newport, and would include a branch from Crindau to Crumlin Bridge. The company also had powers to construct railways from the canal to any coal mines, ironworks or limestone quarries which were within eight miles (13 km) of it.[2]

| Monmouthshire Canal Navigation Act 1797 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Long title | An act for extending the Monmouthshire canal navigation; and for explaining an act, passed is the thirty-second year of the reign of his present Majesty, for making the said canal. |

| Citation | 37 Geo. 3. c. 100 |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 4 July 1797 |

| Monmouthshire Canal Navigation Act 1802 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Long title | An Act for making and maintaining certain Railways, to communicate with the Monmouthshire Canal Navigation; and for enabling the Company of Proprietors of that Navigation to raise a further Sum of Money to complete their Undertaking; and for explaining and amending the Acts passed in the Thirty-second and Thirty-seventh Years of His present Majesty's Reign, relating thereto. |

| Citation | 42 Geo. 3. c. cxv |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 26 June 1802 |

Construction of the canal was supervised by Thomas Dadford Jr.,[3] and further acts of Parliament were obtained as the work progressed. An act of 4 July 1797, the Monmouthshire Canal Navigation Act 1797 (37 Geo. 3. c. 100), gave the company powers to extend the navigation, which resulted in the Newport terminus being moved southwards to Potter Street,[4] while a third act of 26 June 1802, the Monmouthshire Canal Navigation Act 1802 (42 Geo. 3. c. cxv), authorised specific railways, and allowed the company to raise additional finance.[2]

The main line, which opened in February 1796, was 12.5 miles (20.1 km) long, and ran from Newport to Pontnewynydd, via Pontymoile, rising by 447 feet (136 m) through 42 locks. The 11 miles (18 km) Crumlin Arm left the main line at Crindau, rising 358 feet (109 m) through 32 locks to Crumlin (including the Cefn flight of Fourteen Locks), and was opened in 1799.[2] In the late 1840s, a short extension joined the canal to Newport Docks, and hence to the River Usk.[3] Because the canal was isolated from other similar undertakings, Dadford was free to set the size of the locks, and they were designed to take boats with a maximum width of 9 feet 2 inches (2.79 m), a length of 63 feet (19 m) and a draught of three feet (0.91 m).

On the main line, railway branches were constructed from near Pontypool to Blaen-Din Works and Trosnant Furnace. From Crumlin a railway was built to Beaufort Iron Works, which was 10 miles (16 km) long and rose by 619 feet (189 m), and there were additional branches to Sorwy Furnace, Nantyglo Works, and the Sirhowy Railway at Risca.[2]

The Brecknock and Abergavenny Canal

| Brecknock and Abergavenny Canal Act 1793 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Long title | An Act for making and maintaining a Navigable Canal from the Town of Brecknock to the Monmouthshire Canal, near the Town of Pontypool, in the County of Monmouth, and for making and maintaining Railways and Stone Roads from such Canal to the several Iron Works and Mines in the Counties of Brecknock and Monmouth. |

| Citation | 33 Geo. 3. c. 96 |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 28 March 1793 |

This canal was first proposed in 1792 as a separate venture, to link Brecon to the River Usk near Caerleon. The Monmouthshire proprietors invited their potential competitors to alter the plans to create a junction with the Monmouthshire Canal at Pontymoile near Pontypool[5] and share the navigation from there to Newport. An act of Parliament, the Brecknock and Abergavenny Canal Act 1793 (33 Geo. 3. c. 96), was passed on 28 March 1793, allowing the newly formed canal company to raise £100,000 in shares, with an additional £50,000 if required, and to construct railways to link the canal to mines, quarries and iron works.[2]

Initially work concentrated on the railways, with John Dadford overseeing the construction of lines from the collieries at Gellifelen to Llangrwyney Forge, and on to the Abergavenny to Brecon turnpike road. The line was opened in 1794, and later served the canal at Gilwern.[3] It was not until 1795 that Thomas Dadford was appointed as the engineer for the canal itself and construction began in earnest at Penpedairheol near Crickhowell. Work began in 1796 and by late 1797, the canal was open from Gilwern to Llangynidr in Brecknockshire and much of the rest was in hand.[3] However costs, as usual, were higher than expected and, in 1799 Dadford stated that further money was needed to complete the section from Clydach to Brecon. Benjamin Outram was called in to inspect the work and to advise on substituting a railway between Gilwern and Pont-y-Moel. Outram recommended several improvements, in particular the partial rebuilding of the Ashford Tunnel. He was also somewhat critical of the existing railways.

| Brecknock and Abergavenny Canal Act 1804 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Long title | An Act for enabling the Company of Proprietors of the Brecknock and Abergavenny Canal to raise a further Sum of Money for completing the said Canal, and the Works thereunto belonging, and for altering and enlarging the Powers of an Act made in the Thirty-third Year of His present Majesty, for making the said Canal. |

| Citation | 44 Geo. 3. c. xxix |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 3 May 1804 |

| Text of statute as originally enacted | |

The canal was completed and opened to Talybont-on-Usk in late 1799 and through to Brecon in December 1800. Dadford died in 1801, and was replaced as engineer by Thomas Cartwright.[3] The canal company obtained another act of Parliament, the Brecknock and Abergavenny Canal Act 1804 (44 Geo. 3. c. xxix), on 3 May 1804, to authorise the raising of more capital,[2] and the section to Govilon, near Abergavenny was completed in 1805, but the company failed to raise the finance authorised by the 1804 act, and so construction stopped. The company then concentrated on running the canal and railways so far opened, and was running 20 boats by 1806, carrying coal and limestone as their main cargoes.[3]

By 1809 the Monmouthshire Canal was threatening litigation over the uncompleted connection from Gilwern. Help came from Richard Crawshay, the Merthyr Tydfil ironmaster and a major force on the Glamorganshire Canal, who provided a loan of £30,000. This sum enabled the canal company to appoint William Crosley to complete the work, which opened in February 1812.[3]

From the Pontymoile junction, the Brecknock and Abergavenny runs through Llanfoist near Abergavenny and Talybont, ending at a basin in Brecon. The canal is 33 miles (53 km) long and is level for the first 23 miles (37 km) to Llangynidr, where there are five locks.[5] Two miles (3.2 km) below Brecon, the canal crosses the River Usk on an aqueduct at Brynich, and a final lock brings the total rise to 68 ft (21 m).[2] The River Usk provides the main water supply for the canal.[5] A weir near the Brecon Promenade controls the water levels on the river, and one-half mile (0.80 km) of underground culvert brings water through the town to the Theatre Basin.[6] Additional water is taken from a number of streams, where part of the flow is diverted into the canal and the rest flows under an aqueduct to reach the River Usk.[5]

Monmouthshire and Brecon Canal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The tramroads

The Welsh canals were in the main constructed along narrow valleys, where the terrain prevented the easy construction of branches to serve the industries which were located along their routes, but they had the advantage that their enabling acts of Parliament allowed tramways to be constructed, the land for which could be obtained by compulsory purchase, as if the tramway was part of the canal itself. This led to the development of an extensive network of tramways, to serve the many coal and ironstone mines which developed in the area. Dadford was an exponent of "edge rails", where flanged wheels ran on bar section rails, similar to modern railway practice, rather than wheels with no flanges running on L-shaped tram-plates.[3]

Following Dadford's demise, Benjamin Outram was consulted on a number of matters, and recommended that the railways should be converted from edge rails to tram plates. Many of them were converted in this way, but this alteration was not always successful, with users of the Crumlin Bridge to Beaufort Ironworks tramway complaining in 1802 that they had incurred considerable cost to make the transition, only to find that the new tramway was unusable due to poor construction. In 1806, the loaded weights of wagons were reduced, in an attempt to reduce the number of broken tramplates.[4] Ultimately, many of the tramways were converted to standard gauge railways, and so reverted to the flanged wheel system.

The canal acts obtained by the Monmouthshire Canal Company authorised tramways to Aberbeeg, Beaufort, Ebbw Vale, Blaenavon, Blaendare, Nantyglo, Sirhowy and Trosnant.[3] In some cases, these were named specifically because they were longer than 8 miles (13 km) and were not therefore covered by the general provisions of the original act. At least 21 tramways are known to have connected to the Monmouthshire Canal, with a further 13 connecting to the Brecknock and Abergavenny Canal.[4] Some works were eventually connected to both canals. The Beaufort Ironworks was originally connected to Crumlin Bridge by the Ebbw Vale tramway, but the incentives for through trade which the Monmouthshire Canal Company had offered to the Brecknock and Abergavenny Company meant that carriage was cheaper if the goods originated on the northern canal, and so a second tramway was constructed along the heads of the valleys to Gilwern.[3]

Llanhiledd Tramroad

In 1798, the canal company agreed with Sir Richard Salusbury to build a line connecting his collieries to the head of the canal at Crumlin and Llanhilleth. It was not until 1800, however, that Outram was asked to survey the line. The twin track tramway connected by means of an inclined plane to the existing line from the Beaufort Ironworks. Outram's designs were not followed to the letter, probably to save costs, and he expressed his dismay at this.

Monmouthshire Canal Tramway

In 1800, the owners of Sirhowy Ironworks were granted permission to exploit the minerals under Bedwellty Common and build a tramroad to join the canal, with the erection of a works (which was later Tredegar Ironworks).

The Monmouthshire Canal Navigation Act 1802 (42 Geo. 3. c. cxv) sanctioned the construction of tramroads to places within 8 miles (13 km) of the canal, and they therefore built 8 miles (13 km) of tramroad from Newport to a point near Wattsville and Cwmfelinfach. The Sirhowy Tramroad from the Sirhowy Ironworks was built by the ironmasters, to a point one mile (1.6 km) from the canal company section. The mile between crossed the land of Sir Charles Morgan, Baron Tredegar of Tredegar House, who agreed to build the connection across Tredegar Park, in return for tolls for goods crossing his land. This section became known as the "golden mile",[7] because it proved to be quite lucrative for Sir Charles.

The tramroad was constructed between 1802 and 1805[8] or 1806.[9] Branches would be built to the limestone quarries at Trefil (the Trefil Tramroad) and to the Union Ironworks at Rhymney. Two more branches, from Llanarth and Penllwyn to Nine Mile Point Colliery were added in 1824.[9] A major feature of the line was the 'Long Bridge' at Risca, 930 feet (280 m) long with 33 arches each of 24-foot (7.3 m) span averaging 28 feet (8.5 m) high. The bridge was abandoned in 1853, to eliminate the sharp curves at either end, when part of the line was converted to standard gauge, and was demolished in 1905.[10] Conversion of the whole line to standard gauge was completed in 1863, and the Sirhowy Tramroad became the Sirhowy Railway Company in 1865.[9]

Hay Railway

The Hay Railway received authorisation in an act of Parliament, the Hay Railway Act 1811 (51 Geo. 3. c. cxxii), on 25 May 1811. Construction of its winding 24-mile long route took nearly five years and the line was opened on 7 May 1816.[11] The tramway was built to a gauge of 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm). The railway adopted the use of cast-iron L-shaped tramroad plates in its construction. The vertical portions of the two plates were positioned inside the wheels of the tramway wagons and the plates were spiked to stone blocks for stability. The size of the stones, and their spacing, was such that the horses could operate unimpeded.[12] From 1 May 1820, the Hay Railway was joined at its Eardisley terminus, in an end on junction, by the Kington Tramway. Together, the two lines totalled 36 miles in length, comprising the longest continuous plateway to be completed in the United Kingdom.[13]

The Hay Railway operated through rural areas on the borders of England and Wales and was built to transport goods and freight. Passengers were not carried on any official basis. The Hay Railway was absorbed into the Hereford, Hay and Brecon Railway in 1860 and the line was converted to standard gauge[14] for operation by steam locomotives.

Decline and re-opening

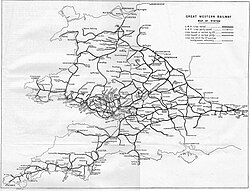

With their network of feeder railways, the canals were profitable. Coal traffic rose from 3,500 tons in 1796 to 150,000 tons in 1809,[15] but the arrival of the railways brought serious decline, and in the 1850s, several schemes to abandon the canals were proposed. The Monmouthshire Company, which had become the Monmouthshire Railway and Canal Company under an act of Parliament[which?] obtained in 1845,[16] bought out the Brecknock and Abergavenny Canal Company in 1865, but the move came too late, and the Monmouthshire Canal gradually closed, while the Brecon line was retained as a water feeder.[5] Control of the canals passed to the Great Western Railway in 1880, and they were consequently nationalised in 1948.[17]

The section of canal from Pontymoile to Pontnewynydd was converted into a railway in 1853, with the loss of 11 locks, and more significantly, much of the water supply to the lower canal.[3] Following the conversion, the next part of the canal to close was the section from Newport to the docks, which lasted until 1879. The rest of the Newport section, to the northern portal of Barrack Hill Tunnel, was closed in 1930, and the Cwmbran section followed in 1954.[18] The Crumlin branch was abandoned as a commercial waterway in 1930,[19] but was retained in water. In February 1946, a serious breach occurred at Abercarn, 2.5 miles (4.0 km) from Crumlin, and although this section of the canal had not been used for 16 years, the breach was repaired. However, the branch was closed just three years later in 1949,[16] and the section from Pontywaun to Crumlin was filled in and used as the route for the A467 road in 1968/9. The rest of the canal was formally abandoned in 1962, but within two years, restoration had begun.[5] Funding for the restoration became available as a result of the National Parks legislation. This was designed to help The Broads in Norfolk and Suffolk, but that area was not designated as a national park, whereas the Brecon Beacons were,[18] and the canal was seen as a valuable amenity in an area of natural beauty. The canal was reopened to Pontymoile in 1970.[6]

The Brecon to Pontypool section was one of seven stretches of canal, formerly designated as 'remainder waterways', which were re-classified by the Transport Act 1968. Under the act, a total of 82 route miles (132 km) were upgraded to cruising waterway standard.[18] The Cefn Flight of Fourteen locks has been recognised as being of international significance, and is on Cadw's list of scheduled monuments.[19]

Restoration of the old Monmouthshire Canal began in 1994, when Torfaen Borough Council raised Crown Bridge in Sebastopol, to give sufficient height for navigation again. The section to Five locks was restored over the next two years, and was formally opened on 24 May 1997 by the Mayor of Torfaen.[3] A new basin at the top of the locks marks the end of the navigable section.

All of the canal route within the jurisdiction of the City of Newport was designated as a conservation area on 21 January 1998. Twenty one of the structures of the canal now have Grade II listed building status.[15] At the Brecon end, the canal terminates at the Theatre Basin, as a result of a project to rebuild the Brecknock Boat Company wharf, which was abandoned and infilled in 1881. Funding was provided by the Welsh Office, the Welsh Arts Council and various private sector bodies. The old wharf buildings have been re-used by the Brecon Theatre, and access is provided by a new canal bridge, named after the engineer Thomas Dadford.[5]

The next section to be opened for navigation was a 2-mile (3.2 km) stretch running from Pentre Lane bridge, just above Tamplin Lock, down through Tyfynnon, Malpas and Gwasted locks to Malpas junction, and then up through Gwasted Lock on the Crumlin branch, to the bottom end of Waen Lock. Work started in January 2008, and was completed in time for the Welsh Waterways Festival held at the end of May 2010. The Inland Waterways Association National Trailboat Festival was held at the same time, and a slipway was rebuilt at Bettws Lane, just below Malpas Lock, to enable the trailboats to be launched easily.[20] Bettws Lane bridge was itself rebuilt to provide more headroom for boats, using grants from the European Regional Development Fund and the Local Regeneration Fund. The grants were secured in 2004, and the bridge was formally opened by the Mayor of Newport on 1 March 2007.[21]

The trust was awarded a grant of £854,500 in 2012 by the Heritage Lottery Fund, to enable the eight locks near Ty Coch to be restored. It will also be used to train people in the skills needed to restore historic canals, and to enable lock gates to be made locally using traditional working methods.[22]

The canal today

Communities on or near the canal include:

On the main arm:

- Brecon [1]

- Talybont-on-Usk [2]

- Llangynidr [3]

- Crickhowell [4]

- Gilwern [5]

- Govilon [6]

- Abergavenny [7]

- Goetre [8]

- Pontypool [9]

- Cwmbran [10]

- Newport [11]

On the Crumlin arm:

Access

Much of the canal towpath[23] is easily walkable[24] along the entire route.[25] The towpath from Brecon to Pontymoile is passable by cyclists over its whole length.[26] The Taff Trail cycle route follows the canal for a few miles from Brecon, but the path after that is not suitable for cyclists with road bikes. National Cycle Network Routes 47 and 49 follow the canals between Cross Keys and Pontypool.

October 2007 breach

On 16 October 2007 a serious breach occurred when part of the canal bank near Gilwern collapsed, causing a number of houses to be evacuated.[27] Eight people were rescued by local fire and emergency services, and the A4077 road between Crickhowell and Gilwern was closed for a period which was expected to be several weeks. Two families were provided with temporary accommodation, and twenty-three hire boats were also affected with cranes being brought in to help them back to their bases.[28]

Contractors Noel Fitzpatrick working for British Waterways managed to reopen the road within a week of the breach occurring. British Waterways announced on 5 November 2007 that a 16-mile (26 km) stretch of the canal from Llanover to Llangynidr would be drained completely, so that a full inspection of the canal structure could be carried out. They stated that they were working with boat owners to move all boats to parts of the canal which would not be affected by this drainage, but that the towpath would remain open during this phase.[29] Subsequently, they announced that a full geotechnical survey would be carried out, and that they expected the stretch to be closed for up to a year.[30] Water levels on this section were reduced significantly, but engineers were then faced with the task of moving upwards of 100,000 fish before it could be drained fully.[31]

At a meeting at Crickhowell on 20 December 2007, British Waterways announced the preliminary results of the investigations: there were over 90 leaks on the section from Talybont to Gilwern, with less leakage on the stretch from Llanover to Goytre Wharf. A press release in February 2008 announced that the total cost of restoration was likely to be around £15 million, with major investment required in the 2008/9 financial year, to repair the breach and to deal with other areas identified as being of top priority. The aim of the work would be to ensure that the canal would be safe and fully open from March 2009, but further work would be required during the following three winters to complete the process. Their actions earned British Waterways the praise of Rhodri Glyn Thomas of the Welsh Assembly, who applauded their "courageous decision" to manage the breach in the way that they had.[32] The repaired canal was officially reopened on 29 March 2009, when a ribbon was cut by Huw Irranca-Davies, the waterways minister, and Rhodri Morgan, the first minister.[33]

Restoration

The canal is located within the boundaries of a number of local authorities, and such bodies are increasingly aware of the benefits and regeneration that a canal restoration project can bring. To this end, the Monmouthshire and Brecon Canals Regeneration Partnership was created as a collaborative effort between the Monmouthshire, Brecon and Abergavenny Canals Trust, Torfaen County Borough Council, Newport City Council, Caerphilly County Borough Council, the Forestry Commission and British Waterways. The partnership submitted a bid to the Big Lottery Living Landmarks Fund for £25 million, this being 75 percent of the estimated cost of restoring the main line from Barrack Hill to Cwmbran, including the construction of a new aqueduct to take the canal over Greenforge Way, and of restoring the Crumlin Branch from Malpas Junction to the bottom of the Cefn flight of Fourteen Locks, including improvements to its water supply. The bid reached the development stage, and the partnership successfully obtained a grant of £250,000 to enable them to undertake a full cost and engineering study for the proposed community based regeneration of the waterway.[34] The partnership continues to meet to discuss the way forward to completing the restoration.[35]

Restoration of the top lock of the Cefn Flight (lock 21) was completed by volunteers in 2003. The Canals Trust and Newport City Council made a joint presentation to the Heritage Lottery Fund for £700,000 to restore the next four locks of the flight, and this was granted on 23 March 2007.[36] The regeneration of the Cefn flight (Fourteen Locks) is a separate project from the main scheme; contractors will work down the flight, while a voluntary team led by the Canals Trust and Waterway Recovery Group will work up from lock 3 on the Allt-yr-yn locks.

There are also plans to connect the southern end of the canal to the River Usk by means of a marina in Crindau. The Crindau Gateway Project is an urban regeneration project for the area around the southern terminus of the canal, which has received £75,000 in funding from the Welsh Assembly to consider the provision of a marina as part of the scheme.[37] A link from the marina to the River Usk would be provided by way of Crindau Pill, an inlet from the river which would be made navigable. This would create sustainability for the project.

As of February 2015, Caerphilly County Borough Council plan to develop the canal corridor from Fourteen Locks to Cwmcarn Forest Drive, and fully restore this part of the canal with a new marina in Risca.[38]

The Canals Trust has taken over the lease of the Canal Centre at Fourteen Locks. An extension has been completed, which houses a meeting room (available for groups to hire) and also a community run tea room. The Canal Centre is now a base for the trust and its restoration work at the centre of the community.

The Welsh Waterways Festival 2010

Organised by the volunteers of the Mon & Brec Canals Trust, the 2010 Welsh Waterways Festival, which included the IWA National Trailboat festival was held at Newport at the end of May 2010. Over 30 boats attended from all over the UK. The boats were able to cruise from Barrack Hill to Pentre Lane in Torfaen Borough for the first time in 84 years, using restored locks at Malpas, Ty Fynnon, and Tamplin. Over 15,000 members of the public turned up over the four days of the festival, which was a tremendous success for Newport and its canal.

See also

- Canals of the United Kingdom

- History of the British canal system

- Monmouthshire and Brecon Canal Tramroads

Bibliography

- Awdry, Christopher (1990). Encyclopaedia of British Railway Companies. Sparkford: Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 1-8526-0049-7. OCLC 19514063. CN 8983.

- Edwards, Lewis A. (1985). Inland Waterways of Great Britain (6th Ed). Imray Laurie Norie & Wilson. ISBN 978-0-85288-081-4.

- Gladwin, D.D. J.M.; Gladwin, J.M. (1991). The Canals of the Welsh Valleys And Their Tramroads. Oakwood Press. ISBN 978-0-85361-412-8.

- McKnight, Hugh (1975). The Shell Book of Inland Waterways. David & Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-8239-4.

- Nicholson (2006). Nicholson Guides Vol 4: Four Counties and the Welsh Canals. Harper Collins Publishers. ISBN 978-0-00-721112-8.

- Norris, John (2007). The Monmouthshire and Brecon Canal (5th Ed.). privately published. ISBN 978-0-9517991-4-7.

- Priestley, Joseph (1831). Historical Account of the Navigable Rivers, Canals, and Railways of Great Britain. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- Simmons, Jack; Biddle, Gordon (1997). The Oxford Companion to British Railway History From 1603 to the 1990s (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-211697-0.

- Ware, Michael E (1989). Britain's Lost Waterways. Moorland Publishing Co Ltd. ISBN 978-0-86190-327-6.

References

- ^ "Monmouthshire & Brecon Canal". Canal and River Trust. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Priestley 1831, pp. 453–455

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Norris 2007

- ^ a b c Gladwin & Gladwin 1991

- ^ a b c d e f g Nicholson 2006

- ^ a b "Monmouthshire and Brecon Canal". Brecon Beacons National Park. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021.

- ^ "Chronicle: Tramroads". Caerphilly County Borough Council. Archived from the original on 29 October 2017.

- ^ "Context for papers in Gwent Records Office". Archives Network Wales.

- ^ a b c "Crosskeys Local History Site". Archived from the original on 12 February 2007.

- ^ "Risca Industrial History Museum". Archived from the original on 21 February 2020.

- ^ Awdry 1990, p. 80

- ^ Simmons & Biddle 1997, pp. 134–135

- ^ Simmons & Biddle 1997, p. 134

- ^ Baughan 1980, page 205

- ^ a b "Conservation". City of Newport. Archived from the original on 10 May 2012.

- ^ a b Ware 1989

- ^ McKnight 1975

- ^ a b c Edwards 1985

- ^ a b "Regeneration: Canals". City of Newport. Archived from the original on 7 February 2012.

- ^ "Welsh Waterways Festival 2010". Newport City Council. Archived from the original on 3 May 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- ^ "Bettws Lane Bridge". Newport City Council. Archived from the original on 3 May 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- ^ "Heritage Lottery Fund winners and losers". Waterways World. June 2012. p. 38. ISSN 0309-1422.

- ^ SO3104 : Bridge over the Monmouthshire & Brecon Canal, near to Croes y Pant geograph.org.uk, accessed 10 March 2019

- ^ SO3104 : Sheep grazing alongside the Monmouthshire & Brecon Canal, near to Croes y Pant geograph.org.uk, accessed 10 March 2019

- ^ SO3104 : Bridge over the Monmouthshire & Brecon Canal, near to Penperlleni geograph.org.uk, accessed 10 March 2019

- ^ "Brecon to Cwmbran along the Monmouthshire and Brecon Canal Towpath". www.cycleroute.com. Archived from the original on 29 September 2020. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- ^ "Homes evacuated in canal collapse". BBC Wales. 16 October 2007. Archived from the original on 18 October 2007.

- ^ "Canal breach plans are drawn up". BBC Wales. 21 October 2007. Archived from the original on 23 October 2007.

- ^ "Monmouthshire and Brecon Canal Inspections". British Waterways. 7 November 2007. Archived from the original on 15 December 2010.

- ^ "Update – Mon & Brec Canal Closure". British Waterways. 13 November 2007. Archived from the original on 27 November 2008.

- ^ "Newsroom: Experts to rehouse 100,000 fish". British Waterways. 11 December 2007. Archived from the original on 27 November 2008.

- ^ "Newsroom: Canal repairs are just the beginning". British Waterways. 4 February 2008. Archived from the original on 27 November 2008.

- ^ "The Reed Warbler (Newsletter)" (PDF). Monmouthshire, Brecon and Abergavenny Canals Trust. May 2009. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2011.

- ^ "Living Links report". City of Newport. Archived from the original on 8 June 2011.

- ^ ST2193 : Canal End Cwmcarn ca. 2006, near to Pontywaun geograph.org.uk, accessed 10 March 2019

- ^ "Historic canal stretch to reopen". BBC Wales. 23 March 2007.

- ^ "Crindau Gateway Urban Regeneration Project". Archived from the original on 27 August 2007.

- ^ "Crumlin Arm Action Plan 2015" (PDF). Caerphilly County Borough Council. p. 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

External links

Media related to Monmouthshire and Brecon Canal at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Monmouthshire and Brecon Canal at Wikimedia Commons- Monmouthshire, Brecon and Abergavenny Canals Trust

- British Waterways Guide

- a 1911 Sunday school and Chapel outing on the canal

- Canal Junction website on the Mon & Brec

- ITV programme on the Brecon and Mon Canal with beautiful pictures

- Sustrans cycle route - Newport to Pontymoel basin

- images & map of mile markers & GWR boundary posts seen along the MonBrec canal