Mongol conquest of the Jin dynasty

| Mongol conquest of the Jin dynasty | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Mongol conquest of China | |||||||

An illustration of the Battle of Yehuling | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

Total: 180,000–210,000

|

| ||||||

| Mongol–Jin War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 蒙金戰爭 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 蒙金战争 | ||||||

| |||||||

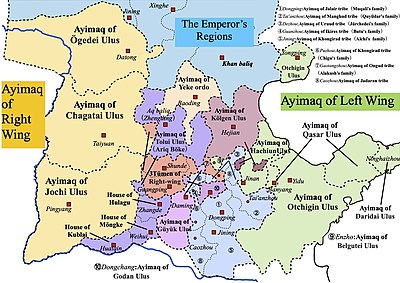

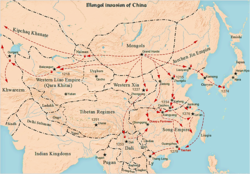

The Mongol conquest of the Jin dynasty, also known as the Mongol–Jin War, was fought between the Mongol Empire and the Jurchen-led Jin dynasty in Manchuria and North China. The war, which started in 1211, lasted over 23 years and ended with the complete conquest of the Jin dynasty by the Mongols in 1234.

Background

The Jurchen rulers of the Jin dynasty collected tribute from some of the nomadic tribes living on the Mongol steppes and encouraged rivalries among them. When the Mongols were unified under Khabul in the 12th century, the Jurchens encouraged the Tatars to destroy them, but the Mongols were able to drive Jin forces out of their territory. The Tatars eventually captured Khabul's successor, Ambaghai, and handed him over to the Jin imperial court. Emperor Xizong of the Jin dynasty had ordered Ambaghai executed by crucifixion (nailed to a wooden mule). The Jin dynasty also conducted regular punitive expeditions against the Mongol nomads, either enslaving or killing them.

In 1210, a delegation arrived at the court of Genghis Khan (r. 1206–27) to proclaim the ascension of Wanyan Yongji to the Jin throne and demanded the submission of the Mongols as a vassal state. Because the Jurchens had defeated the powerful steppe nomads and allied with the Keraites and the Tatars, they claimed sovereignty over all the tribes of the steppe. High court officials in the Jin government defected to the Mongols and urged Genghis Khan to attack the Jin dynasty. But fearful of a trap or some other nefarious scheme, Genghis Khan refused. Upon receiving the order to demonstrate submission, Genghis Khan reportedly turned to the south and spat on the ground; then he mounted his horse, and rode toward the north, leaving the stunned envoy choking in his dust. He gave the Jin emperor a very insulting message which the envoy dared not repeat upon his return to the Jin court. His defiance of the Jin envoys was tantamount to a declaration of war between the Mongols and Jurchens.[4]

After Genghis Khan returned to the Kherlen River, in early 1211, he summoned a kurultai. By organising a long discussion, everyone in the community was included in the process. The Khan prayed privately on a nearby mountain. He removed his hat and belt, bowed down before the Eternal Sky, and recounted the generations of grievances his people held against the Jurchens and detailed the torture and murder of his ancestors. He explained that he had not sought this war against the Jurchens. At the dawn on the fourth day, Genghis Khan emerged with the verdict: "The Eternal Blue Sky has promised us victory and vengeance".[5]

Wanyan Yongji, angry on hearing how Genghis Khan behaved, sent the message to the Khan that "Our Empire is like the sea; yours is but a handful of sand ... How can we fear you?"[6]

Mongol conquest under Genghis Khan

When the conquest of the Tangut-led Western Xia empire started, there were multiple raids between 1207 and 1209.[7] When the Mongols invaded Jin territory in 1211, Ala 'Qush, the chief of the Ongut, supported Genghis Khan and showed him a safe road to the Jin dynasty's heartland. The first important battle between the Mongol Empire and the Jin dynasty was the Battle of Yehuling at a mountain pass in Zhangjiakou which took place in 1211. There, Wanyan Jiujin, the Jin field commander, made a tactical mistake in not attacking the Mongols at the first opportunity. Instead, he sent a messenger to the Mongol side, Shimo Ming'an, who promptly defected and told the Mongols that the Jin army was waiting on the other side of the pass. At this engagement, fought at Yehuling, the Mongols massacred thousands of Jin troops. While Genghis Khan headed southward, his general Jebe travelled even further east into Manchuria and captured Mukden (present-day Shenyang). The Khitan leader Liu-ke had declared his allegiance to Genghis in 1212 and conquered Manchuria from the Jin.

When the Mongol army besieged the Jin central capital, Zhongdu (present-day Beijing), in 1213, Li Ying, Li Xiong and a few other Jin generals assembled a militia of more than 10,000 men who inflicted several defeats on the Mongols. The Mongols smashed the Jin armies, each numbering in the hundreds of thousands, and broke through Juyong Pass and Zijing Gap by November 1213.[8] From 1213 until early 1214, the Mongols pillaged the entire North China plain. In 1214, Genghis Khan surrounded the court of the Golden Khan in Zhongdu.[9] The Jin general Hushahu had murdered the emperor Wanyan Yongji and enthroned Wanyan Yongji's nephew, Emperor Xuanzong. When the Mongols besieged Zhongdu, the Jin government temporarily agreed to become a tributary state of the Mongol Empire, presenting to Genghis Khan Jurchen Princess Qiguo, daughter of Jurchen Jin emperor Wanyan Yongji. But when the Mongols withdrew in 1214, believing the war was over after being given a large tribute by the Jurchens, Li Ying wanted to ambush them on the way with his forces (which had grown to several tens of thousands). However, the Jin ruler, Emperor Xuanzong, was afraid of offending the Mongols again so he stopped Li Ying. Emperor Xuanzong and the general Zhuhu Gaoqi then decided to shift the capital south to Kaifeng, above the objections of many courtiers including Li Ying. From then on, the Jin were strictly on the defensive and Zhongdu fell to the Mongols in 1215.

Jurchen Princess Qiguo was married to Genghis Khan in exchange for relieving the Mongol siege upon Zhongdu (Beijing) in the Mongol conquest of the Jin dynasty.[10]

After the shift of the Jin capital to Kaifeng, the Jin chancellor Wanyan Chenghui and general Moran Jinzhong were left to guard Zhongdu. At this point, one of the Jin armies defected to the Mongols and launched an attack on Zhongdu from the south, taking Lugou Bridge. Genghis Khan then dispatched his troops to attack Zhongdu again, led by the surrendered Khitan generals Shimo Ming'an, Yelü Ahai and Yelü Tuhua. Moran Jinzhong's second-in-command, Pucha Qijin, surrendered to the Mongols with all the troops under him, throwing Zhongdu into crisis. Emperor Xuanzong then sent reinforcements north: Yongxi leading the troops from Zhending and Zhongshan (numbers not given), and Wugulun Qingshou leading 18,000 imperial guards, 11,000 infantry and cavalry from the southwestern route, and 10,000 soldiers from Hebei Province, with Li Ying in charge of the supply train. Zhongdu fell to the Mongols on June 1, 1215. Then they systematically rooted out all resistance in Shanxi, Hebei and Shandong provinces from 1217 to 1223. Genghis Khan did however need to turn his attention to the east in 1219, due to another event in Central Asia and Persia.

Muqali's advance

In 1223, the Mongol general Muqali had struck into Shaanxi Province, attacking Chang'an when Genghis Khan was attacking Khwarezmia. The garrison in Chang'an, 200,000 under Wanyan Heda, was too strong and Muqali had to turn to besieging Feng County with 100,000 men. The siege dragged on for months and the Mongols were harassed by local militia, while Jin reinforcements were about to arrive. Muqali then died of illness, and the Mongols retreated. This was the siege in which the Western Xia troops supporting the Mongols gave up and went home, incurring the wrath of Genghis Khan. In the wars against the Mongols, therefore, the Jin relied heavily on subjects or allies like the Uighurs, Tanguts and Khitans to supply cavalry.

Mongol conquest under Ögedei Khan

When Ögedei Khan succeeded his father, he rebuffed Jin offers of peace talks but the Jin officers murdered Mongol envoys.[11]

Jin armies under Emperor Aizong successfully stopped several Mongol offensives, with major victories in the process, such as at the Battle of Dachangyuan in 1229, Battle of Weizhou (1230), Battle of Daohuigu (1231).

The Kheshig commander Doqolqu was dispatched to attempt a frontal attack on Tong Pass, but Wanyan Heda defeated him and forced Subutai to withdraw in 1230. In 1231, the Mongols attacked again and finally took Fengxiang. The Jin garrison in Chang'an panicked and abandoned the city, pulling back to Henan Province with all the city's population. One month later, the Mongols decided to use a three-pronged attack to converge on Kaifeng from north, east and west. The western force under Tolui would start from Fengxiang, enter Tong Pass, and then pass through Song territory at the Han River (near Xiangyang) to reemerge south of Kaifeng to catch the Jurchens by surprise.

Wanyan Heda learned of this plan and led 200,000 men to intercept Tolui. At Dengzhou, he set an ambush in a valley with several tens of thousands of cavalry hidden behind the crest of either mountain, but Tolui's spies alerted him and he kept his main force with the supply train, sending only a smaller force of light cavalry to skirt around the valley and attack the Jin troops from behind. Wanyan Heda saw that his plan had been foiled and prepared his troops for a Mongol assault. At Mount Yu, southwest of Dengzhou, the two armies met in a pitched battle. The Jin army had an advantage in numbers, and fought fiercely. The Mongols then withdrew from Mount Yu by about 30 li, and Tolui changed his strategy. Leaving a part of his force to keep Wanyan Heda occupied, he sent most of his men to strike northwards at Kaifeng in several dispersed contingents to avoid alerting Heda.

On the way from Dengzhou to Kaifeng, the Mongols easily took county after county, and burnt all the supplies they captured so as to cut off Wanyan Heda's supply lines. Wanyan Heda was forced to withdraw, and ran into the Mongols at Three-peaked Hill in Junzhou. At this point, the Jin troops on the Yellow River were also diverted southwards to meet Tolui's attack, and the Mongol northern force under Ögedei Khan seized this opportunity to cross the frozen river and join up with Tolui – even at this point, their combined strength was only about 50,000. By 1232, the Jurchen ruler, Emperor Aizong, was besieged in Kaifeng. They together smashed the Jin forces. Ögedei Khan soon departed, leaving the final conquest to his generals.

Mongol–Song alliance

In 1233, Emperor Aizong dispatched diplomats to implore the Song for supplies. Jin envoys reported to the Song that the Mongols would invade the Song after they were done with the Jin – a forecast that would later be proven true – but the Song ignored the warning and rebuffed the request. They instead formed an alliance with the Mongols against the Jin. The Song provided supplies to the Mongols in return for parts of Henan.

The fall of the Jin dynasty

Wanyan Heda's army still had more than 100,000 men after the battle at Mount Yu, and the Mongols adopted a strategy of exhausting the enemy. The Jin troops had little rest all the way from Dengzhou, and had not eaten for three days because of the severing of their supply lines. Their morale was plummeting and their commanders were losing confidence. When they reached Sanfengshan (Three-peaked Hill), a snowstorm suddenly broke out, and it was so cold that the faces of the Jin troops went as white as corpses, and they could hardly march. Rather than attack them when they were desperate with their backs to the wall, the Mongols left them an escape route and then ambushed them when they let down their guard during the retreat. The Jin army collapsed without a fight, and the Mongols pursued the fleeing Jin troops relentlessly. Wanyan Heda was killed, and most of his commanders also lost their lives. After the Battle of Sanfengshan, Mongol troops took the city of Yuzhou. Kaifeng was doomed and Emperor Aizong soon abandoned the city and entered Hebei Province in a vain attempt to reestablish himself there. Thousands of people offered a stubborn resistance to the Mongols, who entrusted the conduct of the attack to Subutai, the most daring of all their commanders. Emperor Aizong was driven south again, and by this time Kaifeng had been taken by the Mongols so he established his new capital at Caizhou (present-day Runan County, Henan Province). Subutai wished to massacre the whole of the population. But Yelü Chucai was more humane, and under his advice Ögedei Khan rejected the cruel proposal.

The Jurchens used fire arrows against the Mongols during the defence of Kaifeng in 1232. The Mongols adopted this weapon in later conquests.[12]

In 1233, after Emperor Aizong had abandoned Kaifeng and failed to raise a new army for himself in Hebei, he returned to Henan and established his base in Guide (present-day Anyang). Scattered Jin armies began to gather at Guide from the surrounding region and Hebei, and the supplies in the city could no longer feed all these soldiers. Thus Emperor Aizong was left with only 450 Han Chinese troops under the command of Pucha Guannu and 280 men under Ma Yong to guard the city, and dispersed the rest of the troops to forage in Su (in Anhui Province), Xu (present-day Xuzhou, Jiangsu Province), and Chen (present-day Huaiyang, Henan Province).

Pucha Guannu then launched a coup with his troops, killing Ma Yong and more than 300 other courtiers, as well as about 3,000 officers, palace guards and civilians who refused to cooperate with him. He made Emperor Aizong a puppet ruler and became the real master of the Jin imperial court. At this point the Mongols had arrived outside Guide and were preparing to besiege the city. The Mongol general Sajisibuhua had set up camp north of the city, on the bank of a river. Guannu then led his 450 troops out on boats from the southern gate at night, armed with fire-lances. They rowed along the river by the eastern side of the city, reaching the Mongol camp early in the morning. Emperor Aizong watched the battle from the northern gate of the city, with his imperial boat prepared for him to flee to Xuzhou if the Jin troops were defeated.

The Jin troops assaulted the Mongol camp from two directions, using their fire-lances to throw the Mongols into a panic. More than 3,500 Mongols drowned in the river while trying to flee, and the Mongol stockades were all burned to the ground. Sajisibuhua was also killed in the battle. Pucha Guannu had achieved a remarkable victory and was promoted by Emperor Aizong. But Guide was not defensible in the long term, and the other courtiers urged Emperor Aizong to move to Caizhou, which had stronger walls and more provisions and troops. Pucha Guannu opposed the move, afraid that his power base would be weakened and arguing that Caizhou's advantages had been overstated.

The Han Chinese general Shi Tianze led troops to pursue Emperor Aizong as he retreated, and destroyed an 80,000-strong Jin army led by Wanyan Chengyi (完顏承裔) at Pucheng (蒲城).

Three months later, Emperor Aizong used a plot to assassinate Guannu, and then quickly began preparations to move to Caizhou. By the time new reports reached him that Caizhou was still too weak in defences, troops and supplies, he was already on the way there. The fate of the Jin dynasty was then sealed for good, despite the earlier victory against great odds at Guide.

The Southern Song dynasty, wishing to give the Jin dynasty the coup de grâce, declared war upon the Jurchens, and placed a large army in the field. The remainder of the Jin army took shelter in Caizhou, where they were closely besieged by the Mongols on one side and the Song army on the other. Driven thus into a corner, the Jurchens fought with the courage of despair and long held out against the combined efforts of their enemies. At last, Emperor Aizong saw that the struggle could not be prolonged, and he prepared himself to end his life. When the enemy breached the city walls, Emperor Aizong committed suicide after passing the throne to his general Wanyan Chenglin. Wanyan Chenglin, historically known as Emperor Mo, ruled for less than a day before he was finally killed in battle. Thus the Jin dynasty came to an end on February 9, 1234.

There are great men of the vanquished Jin who have gotten mixed up in odd jobs falling as low as butchering and peddling, or leaving to become Yellow Caps. All of them are still referred to by their old government [titles]. The family of Pacification Commissioner Wang has a number of men who push carts and are called 'Transport Commissioner' or 'Attendant Courtier.' In Changchun Palace, 'Palace of Long Spring,' there are many gentlemen of the vanquished Jin court, who by being there avoid baijiao, escape taxes and corvée labor, and receive clothing and food. It is to a great extent the cause for the people's sorrow and distress.[13]

— Zhao Gong

Mongol policies

James Waterson cautioned against attributing the population drop in northern China to Mongol slaughter since much of the population may have moved to southern China under the Southern Song or died of disease and famine as agricultural and urban city infrastructure were destroyed.[14] The Mongols spared cities from massacre and sacking if they surrendered, such as Kaifeng, which was surrendered to Subetai by Xu Li,[15] Yangzhou, which was surrendered to Bayan by Li Tingzhi's second in command after Li Tingzhi was executed by the Southern Song,[16] and Hangzhou, which was spared from sacking when it surrendered to Kublai Khan.[17] Han Chinese and Khitan soldiers defected en masse to Genghis Khan against the Jurchen Jin dynasty.[18] Towns which surrendered were spared from sacking and massacre by Kublai Khan.[19] The Khitan reluctantly left their homeland in Manchuria as the Jin moved their primary capital from Beijing south to Kaifeng and defected to the Mongols.[20]

Many Han Chinese and Khitans defected to the Mongols to fight against the Jin dynasty. Two Han Chinese leaders, Shi Tianze and Liu Heima (劉黑馬),[21] and the Khitan Xiao Zhala (蕭札剌) defected and commanded the three tumens in the Mongol army.[22] Liu Heima and Shi Tianze served Genghis Khan's successor, Ögedei Khan.[23] Liu Heima and Shi Tianxiang led armies against Western Xia for the Mongols.[24] There were four Han tumens and three Khitan tumens, with each tumen consisting of 10,000 troops. The three Khitan generals Shimo Beidi'er (石抹孛迭兒), Tabuyir (塔不已兒), and Xiao Zhongxi (蕭重喜; Xiao Zhala's son) commanded the three Khitan tumens and the four Han generals Zhang Rou (張柔), Yan Shi (嚴實), Shi Tianze and Liu Heima commanded the four Han tumens under Ögedei Khan.[25][26][27][28] Shi Tianze, Zhang Rou, Yan Shi and other Han Chinese who served in the Jin dynasty and defected to the Mongols helped build the structure for the administration of the new Mongol state.[29]

The Mongols valued physicians, craftsmen and religious clerics and ordered them to be spared from death and brought to them when cities were taken in northern China.[30]

The Han Chinese nobles Duke Yansheng and Celestial Masters continued possessing their titles in the Mongol empire and Yuan dynasty since the previous dynasties.

See also

Notes

- ^ 800,000 infantry and 150,000 elite cavalry spread across the Great Wall

References

- ^ Haywood, John; Jotischky, Andrew; McGlynn, Sean (1998). Historical Atlas of the Medieval World, AD 600–1492. Barnes & Noble. p. 3.21. ISBN 978-0-760-71976-3.

- ^ Mongol Warrior 1200–1350 Publisher: Osprey Publishing

- ^ a b Sverdrup, Carl (2010). "Numbers in Mongol Warfare". Journal of Medieval Military History. 8. Boydell Press: 109–117. doi:10.1515/9781846159022-004. ISBN 978-1-843-83596-7.

- ^ Weatherford, Jack (2004), "2: Tale of Three Rivers", Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World, New York: Random House/Three Rivers Press, p. 83, ISBN 978-0-609-80964-8

- ^ The Secret History of the Mongols

- ^ Meng Ta Peu Lu, Aufzeichnungen über die Mongolischen Tatan von Chao Hung, 1221, p. 61.

- ^ Weatherford 2004 p. 85

- ^ Atwood, Christopher Pratt (2004). Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. Facts on File. p. 277. ISBN 9780816046713.

- ^ Weatherford 2004 p. 96.

- ^ Broadbridge, Anne F. (2018). Women and the Making of the Mongol Empire (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-1108636629.

- ^ Herbert Franke; Denis Twitchett; John King Fairbank (1994). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States. Cambridge University Press. p. 263.

- ^ Gloria Skurzynski (2010). This Is Rocket Science: True Stories of the Risk-Taking Scientists Who Figure Out Ways to Explore Beyond Earth (illustrated ed.). National Geographic Books. p. 1958. ISBN 978-1-4263-0597-9.

In A.D. 1232 an army of 30,000 Mongol warriors invaded the Chinese city of Kai-fung-fu, where the Chinese fought back with fire arrows ... Mongol leaders learned from their enemies and found ways to make fire arrows even more deadly as their invasion spread toward Europe. On Christmas Day 1241 Mongol troops used fire arrows to capture the city of Budapest in Hungary, and in 1258 to capture the city of Baghdad in what is now Iraq.

- ^ Garcia 2012, pp. 337–338.

- ^ Waterson, James (2013). Defending Heaven: China's Mongol Wars, 1209–1370. Casemate Publishers. ISBN 978-1783469437.

- ^ Waterson, James (2013). Defending Heaven: China's Mongol Wars, 1209–1370. Casemate Publishers. ISBN 978-1783469437.

- ^ Waterson, James (2013). Defending Heaven: China's Mongol Wars, 1209–1370. Casemate Publishers. ISBN 978-1783469437.

- ^ Balfour, Alan H.; Zheng, Shiling (2002). Balfour, Alan H. (ed.). Shanghai (illustrated ed.). Wiley-Academy. p. 25. ISBN 0471877336.

- ^ Waterson, James (2013). Defending Heaven: China's Mongol Wars, 1209–1370. Casemate Publishers. ISBN 978-1783469437.

- ^ Coatsworth, John; Cole, Juan Ricardo; Hanagan, Michael P.; Perdue, Peter C.; Tilly, Charles; Tilly, Louise (2015). Global Connections. Vol. 1 of Global Connections: Politics, Exchange, and Social Life in World History (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 356. ISBN 978-0521191890.

- ^ Man, John (2013). Genghis Khan: Life, Death, and Resurrection. Macmillan. ISBN 978-1466861565.

- ^ Collectif (2002). Revue bibliographique de sinologie 2001. Éditions de l'École des hautes études en sciences sociales. p. 147.

- ^ May, Timothy Michael (2004). The Mechanics of Conquest and Governance: The Rise and Expansion of the Mongol Empire, 1185–1265. University of Wisconsin--Madison. p. 50.

- ^ Schram, Stuart Reynolds (1987). Foundations and Limits of State Power in China. European Science Foundation by School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. p. 130.

- ^ Gary Seaman; Daniel Marks (1991). Rulers from the steppe: state formation on the Eurasian periphery. Ethnographics Press, Center for Visual Anthropology, University of Southern California. p. 175.

- ^ "窝阔台汗己丑年汉军万户萧札剌考辨--兼论金元之际的汉地七万户 A Study of XIAO Zha-la the Han Army Commander of 10,000 Families in the Year of 1229 during the Period of Khan (O)gedei". wanfangdata.com.cn. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ "窝阔台汗己丑年汉军万户萧札剌考辨-兼论金元之际的汉地七万户-国家哲学社会科学学术期刊数据库". Nssd.org. Archived from the original on 2020-04-13. Retrieved 2018-02-26.

- ^ "新元史/卷146" [New Yuan History/Volume 146]. Wikisource (in Chinese).

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-05-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Chan, Hok-Lam (1997). "A Recipe to Qubilai Qa'an on Governance: The Case of Chang Te-hui and Li Chih". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 7 (2). Cambridge University Press: 257–283. doi:10.1017/S1356186300008877. S2CID 161851226.

- ^ Shinno, Reiko (2016). "2 The Mongol conquest and the new configuration of power, 1206–76". The Politics of Chinese Medicine Under Mongol Rule. Needham Research Institute Series (illustrated ed.). Routledge. pp. 24–29. ISBN 978-1317671602.

Bibliography

- Garcia, Chad D. (2012), A New Kind of Northerner[ISBN missing]