Mojave Desert

| Mojave Desert Hayyikwiir Mat'aar (Mohave) Desierto de Mojave (Spanish) | |

|---|---|

Sand dunes in Death Valley | |

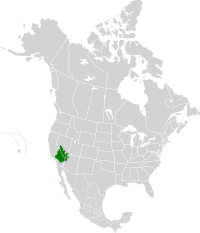

Location within North America | |

| Ecology | |

| Realm | Nearctic |

| Biome | Deserts and xeric shrublands |

| Borders | |

| Bird species | 230[1] |

| Mammal species | 98[1] |

| Geography | |

| Area | 81,000 km2 (31,000 sq mi) |

| Country | United States |

| States | |

| Coordinates | 35°N 116°W / 35°N 116°W |

| Rivers | Colorado River, Mojave River |

| Climate type | Cold desert (BWk) and hot desert (BWh) |

| Conservation | |

| Conservation status | Relatively Stable/Intact[2] |

The Mojave Desert (/moʊˈhɑːvi, mə-/ ⓘ;[3][4][5] Mohave: Hayikwiir Mat'aar;[6] Spanish: Desierto de Mojave) is a desert in the rain shadow of the southern Sierra Nevada mountains and Transverse Ranges in the Southwestern United States.[7][2] Named for the indigenous Mohave people, it is located primarily in southeastern California and southwestern Nevada, with small portions extending into Arizona and Utah.[8][2]

The Mojave Desert, together with the Sonoran, Chihuahuan, and Great Basin deserts, form a larger North American desert. Of these, the Mojave is the smallest and driest. It displays typical basin and range topography, generally having a pattern of a series of parallel mountain ranges and valleys. It is also the site of Death Valley, which is the lowest elevation in North America. The Mojave Desert is often colloquially called the "high desert", as most of it lies between 2,000 and 4,000 feet (610 and 1,220 m). It supports a diversity of flora and fauna.

The 54,000 sq mi (140,000 km2) desert supports a number of human activities, including recreation, ranching, and military training.[9] The Mojave Desert also contains various silver, tungsten, iron and gold deposits.[10]: 124

The spelling Mojave originates from the Spanish language, while the spelling Mohave comes from modern English. Both are used today, although the Mojave Tribal Nation officially uses the spelling Mojave. Mojave is a shortened form of Hamakhaave, an endonym in their native language, which means "beside the water".[11]

Geography

The Mojave Desert is a desert bordered to the west by the Sierra Nevada mountain range and the California montane chaparral and woodlands, and to the south and east by the Sonoran Desert. The boundaries to the east of the Mojave Desert are less distinctive than the other boundaries because there is no presence of an indicator species, such as the Joshua tree (Yucca brevifolia),[13] which is endemic to the Mojave Desert. The Mojave Desert is distinguished from the Sonoran Desert and other deserts adjacent to it by its warm temperate climate, as well as flora and fauna such as ironwood (Olneya tesota), blue Palo Verde (Parkinsonia florida), chuparosa (Justicia californica), spiny menodora (Menodora spinescens), desert senna (Cassia armata), California dalea (Psorothamnus arborescens), California fan palm (Washingtonia filifera) and goldenhead (Acamptopappus shockleyi). Along with these other factors, these plants differentiate the Mojave from the nearby Sonoran Desert.[2]

The Mojave Desert is bordered by the San Andreas Fault to the southwest and the Garlock fault to the north. The mountains elevated along the length of the San Andreas fault provide a clear border between the Mojave Desert and the coastal regions to the west.[10] The Garlock fault separates the Mojave Desert from the Sierra Nevada and Tehachapi mountains, which provide a natural border to the Mojave Desert. There are also abundant alluvial fans, which are called bajadas, that form around the mountains within the Mojave Desert and extend down toward the low altitude basins,[13] which contain dried lake beds called playas, where water generally collects and evaporates, leaving large volumes of salt. These playas include Rogers Dry Lake and China Lake. Dry lakes are a noted feature of the Mojave landscape.[2] The Mojave Desert is also home to the Devils Playground, about 40 miles (64 km) of dunes and salt flats going in a northwest-southeasterly direction. The Devil's Playground is a part of the Mojave National Preserve and is between the town of Baker, California and the Providence Mountains. The Cronese Mountains are within the Devil's Playground.

There are very few surface rivers in the Mojave Desert, but two major rivers generally flow underground. One is the intermittent Mojave River, which begins in the San Bernardino mountains and disappears underground in the Mojave Desert.[14] The other is the Amargosa River, which flows partly underground through the Mojave Desert along a southward path.[15] The Manix, Mojave, and the Little Mojave lakes are all large but shallow.[13]: 7 Soda Lake is the principal saline basin of the Mojave Desert. Natural springs are typically rare throughout the Mojave Desert,[13]: 19 but there are two notable springs, Ash Meadows and Oasis Valley. Ash Meadows is formed from several other springs, which all draw from deep underground. Oasis Valley draws from the nearby Amargosa River.

Climate

Extremes in temperatures throughout the seasons characterize the climate of the Mojave Desert. Freezing temperatures and strong winds are not uncommon in the winter, as well as precipitation such as rain and snow in the mountains. In contrast, temperatures above 100 °F (38 °C) are not uncommon during the summer months.[16] There is an annual average precipitation of 2 to 6 inches (51 to 152 mm), although regions at high altitudes such as the portion of the Mojave Desert in the San Gabriel mountains may receive more rain.[10][8] Most of the precipitation in the Mojave comes from the Pacific Cyclonic storms that are generally present passing eastward in November to April.[10] Such storms generally bring rain and snow only in the mountainous regions, as a result of the effect of the mountains, which creates a drying effect on its leeward slopes.[10]

During the late summer months, there is also the possibility of strong thunderstorms, which bring heavy showers or cloudbursts. These storms can result in flash flooding.[17]

The Mojave Desert has not historically supported a fire regime because of low fuel loads and connectivity. However, in the last few decades, invasive annual plants such as some within the genera Bromus, Schismus and Brassica have facilitated fires by serving as a fuel bed. This has significantly altered many areas of the desert. At higher elevations, fire regimes are regular but infrequent.[18]

| Climate data for Furnace Creek, Death Valley, California (1991–2020 normals,[a] extremes 1911–present). Elevation −190 ft (−58 m). | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 90 (32) |

102 (39) |

108 (42) |

113 (45) |

122 (50) |

131 (55) |

134.1 (56.7) |

131 (55) |

125 (52) |

118 (48) |

98 (37) |

89 (32) |

134.1 (56.7) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 78.4 (25.8) |

85.1 (29.5) |

95.4 (35.2) |

106.0 (41.1) |

113.6 (45.3) |

122.0 (50.0) |

125.9 (52.2) |

123.4 (50.8) |

118.1 (47.8) |

106.2 (41.2) |

90.0 (32.2) |

77.8 (25.4) |

126.7 (52.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 67.2 (19.6) |

73.7 (23.2) |

82.6 (28.1) |

91.0 (32.8) |

100.7 (38.2) |

111.1 (43.9) |

117.4 (47.4) |

115.9 (46.6) |

107.7 (42.1) |

93.3 (34.1) |

77.4 (25.2) |

65.6 (18.7) |

92.0 (33.3) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 54.9 (12.7) |

61.3 (16.3) |

69.8 (21.0) |

77.9 (25.5) |

87.8 (31.0) |

97.5 (36.4) |

104.2 (40.1) |

102.3 (39.1) |

93.4 (34.1) |

78.9 (26.1) |

64.0 (17.8) |

53.4 (11.9) |

78.8 (26.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 42.5 (5.8) |

49.0 (9.4) |

57.1 (13.9) |

64.8 (18.2) |

75.0 (23.9) |

84.0 (28.9) |

91.0 (32.8) |

88.7 (31.5) |

79.1 (26.2) |

64.4 (18.0) |

50.5 (10.3) |

41.1 (5.1) |

65.6 (18.7) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 30.5 (−0.8) |

36.1 (2.3) |

42.8 (6.0) |

49.8 (9.9) |

58.5 (14.7) |

67.9 (19.9) |

78.3 (25.7) |

75.3 (24.1) |

65.4 (18.6) |

49.5 (9.7) |

35.9 (2.2) |

29.0 (−1.7) |

28.0 (−2.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 15 (−9) |

20 (−7) |

26 (−3) |

35 (2) |

42 (6) |

49 (9) |

62 (17) |

65 (18) |

41 (5) |

32 (0) |

24 (−4) |

19 (−7) |

15 (−9) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.37 (9.4) |

0.52 (13) |

0.25 (6.4) |

0.10 (2.5) |

0.03 (0.76) |

0.05 (1.3) |

0.10 (2.5) |

0.10 (2.5) |

0.20 (5.1) |

0.12 (3.0) |

0.10 (2.5) |

0.26 (6.6) |

2.20 (56) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 2.4 | 2.9 | 2.0 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.6 | 16.0 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 217 | 226 | 279 | 330 | 372 | 390 | 403 | 372 | 330 | 310 | 210 | 186 | 3,625 |

| Source: NOAA[19][20] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Las Vegas, Nevada (1991–2020 normals,[b] extremes 1937–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 77 (25) |

87 (31) |

92 (33) |

99 (37) |

109 (43) |

117 (47) |

117 (47) |

116 (47) |

114 (46) |

103 (39) |

87 (31) |

78 (26) |

117 (47) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 68.7 (20.4) |

74.2 (23.4) |

84.3 (29.1) |

93.6 (34.2) |

101.8 (38.8) |

110.1 (43.4) |

112.9 (44.9) |

110.3 (43.5) |

105.0 (40.6) |

94.6 (34.8) |

80.5 (26.9) |

67.9 (19.9) |

113.6 (45.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 58.5 (14.7) |

62.9 (17.2) |

71.1 (21.7) |

78.5 (25.8) |

88.5 (31.4) |

99.4 (37.4) |

104.5 (40.3) |

102.8 (39.3) |

94.9 (34.9) |

81.2 (27.3) |

67.1 (19.5) |

56.9 (13.8) |

80.5 (26.9) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 49.5 (9.7) |

53.5 (11.9) |

60.8 (16.0) |

67.7 (19.8) |

77.3 (25.2) |

87.6 (30.9) |

93.2 (34.0) |

91.7 (33.2) |

83.6 (28.7) |

70.4 (21.3) |

57.2 (14.0) |

48.2 (9.0) |

70.1 (21.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 40.5 (4.7) |

44.1 (6.7) |

50.5 (10.3) |

56.9 (13.8) |

66.1 (18.9) |

75.8 (24.3) |

82.0 (27.8) |

80.6 (27.0) |

72.4 (22.4) |

59.6 (15.3) |

47.3 (8.5) |

39.6 (4.2) |

59.6 (15.3) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 29.8 (−1.2) |

32.9 (0.5) |

38.7 (3.7) |

45.2 (7.3) |

52.8 (11.6) |

62.2 (16.8) |

72.9 (22.7) |

70.8 (21.6) |

60.8 (16.0) |

47.4 (8.6) |

35.2 (1.8) |

29.0 (−1.7) |

27.4 (−2.6) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 8 (−13) |

16 (−9) |

19 (−7) |

31 (−1) |

38 (3) |

48 (9) |

56 (13) |

54 (12) |

43 (6) |

26 (−3) |

15 (−9) |

11 (−12) |

8 (−13) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.56 (14) |

0.80 (20) |

0.42 (11) |

0.20 (5.1) |

0.07 (1.8) |

0.04 (1.0) |

0.38 (9.7) |

0.32 (8.1) |

0.32 (8.1) |

0.32 (8.1) |

0.30 (7.6) |

0.45 (11) |

4.18 (106) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.2 (0.51) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 3.1 | 4.1 | 2.8 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 3.0 | 25.8 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 45.1 | 39.6 | 33.1 | 25.0 | 21.3 | 16.5 | 21.1 | 25.6 | 25.0 | 28.8 | 37.2 | 45.0 | 30.3 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 22.1 (−5.5) |

23.7 (−4.6) |

23.9 (−4.5) |

24.1 (−4.4) |

28.2 (−2.1) |

30.9 (−0.6) |

40.6 (4.8) |

44.1 (6.7) |

37.0 (2.8) |

30.4 (−0.9) |

25.3 (−3.7) |

22.3 (−5.4) |

29.4 (−1.5) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 245.2 | 246.7 | 314.6 | 346.1 | 388.1 | 401.7 | 390.9 | 368.5 | 337.1 | 304.4 | 246.0 | 236.0 | 3,825.3 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 79 | 81 | 85 | 88 | 89 | 92 | 88 | 88 | 91 | 87 | 80 | 78 | 86 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity, dew point and sun 1961–1990)[21][22][23] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Searchlight, Nevada. (Elevation 3,550 ft (1,080 m)) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 77 (25) |

81 (27) |

90 (32) |

94 (34) |

102 (39) |

110 (43) |

111 (44) |

110 (43) |

107 (42) |

98 (37) |

86 (30) |

75 (24) |

111 (44) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 53.7 (12.1) |

58.4 (14.7) |

65.0 (18.3) |

73.1 (22.8) |

82.5 (28.1) |

92.7 (33.7) |

97.6 (36.4) |

95.4 (35.2) |

89.0 (31.7) |

77.0 (25.0) |

63.6 (17.6) |

54.4 (12.4) |

75.2 (24.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 35.6 (2.0) |

38.3 (3.5) |

41.8 (5.4) |

48.0 (8.9) |

55.9 (13.3) |

64.8 (18.2) |

71.4 (21.9) |

69.6 (20.9) |

63.9 (17.7) |

53.9 (12.2) |

43.0 (6.1) |

36.4 (2.4) |

51.9 (11.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 7 (−14) |

11 (−12) |

20 (−7) |

27 (−3) |

30 (−1) |

40 (4) |

52 (11) |

51 (11) |

41 (5) |

23 (−5) |

15 (−9) |

8 (−13) |

7 (−14) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.92 (23) |

0.96 (24) |

0.77 (20) |

0.40 (10) |

0.20 (5.1) |

0.11 (2.8) |

0.91 (23) |

1.08 (27) |

0.61 (15) |

0.52 (13) |

0.43 (11) |

0.79 (20) |

7.70 (196) |

| Source: The Western Regional Climate Center[24] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Mount Charleston Lodge, Nevada. (Elevation 7,420 ft (2,260 m)) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 70 (21) |

69 (21) |

73 (23) |

79 (26) |

86 (30) |

93 (34) |

98 (37) |

93 (34) |

90 (32) |

83 (28) |

79 (26) |

69 (21) |

98 (37) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 44.0 (6.7) |

43.4 (6.3) |

48.8 (9.3) |

54.8 (12.7) |

64.4 (18.0) |

74.1 (23.4) |

79.4 (26.3) |

78.2 (25.7) |

71.7 (22.1) |

61.4 (16.3) |

51.6 (10.9) |

44.3 (6.8) |

59.7 (15.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 19.2 (−7.1) |

19.8 (−6.8) |

23.5 (−4.7) |

28.2 (−2.1) |

36.4 (2.4) |

44.1 (6.7) |

52.0 (11.1) |

50.6 (10.3) |

43.5 (6.4) |

34.5 (1.4) |

26.0 (−3.3) |

19.4 (−7.0) |

33.1 (0.6) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −11 (−24) |

−15 (−26) |

1 (−17) |

7 (−14) |

16 (−9) |

17 (−8) |

31 (−1) |

30 (−1) |

17 (−8) |

9 (−13) |

1 (−17) |

−18 (−28) |

−18 (−28) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.83 (72) |

3.51 (89) |

1.92 (49) |

1.23 (31) |

0.70 (18) |

0.29 (7.4) |

2.13 (54) |

1.89 (48) |

1.69 (43) |

1.96 (50) |

1.31 (33) |

3.61 (92) |

23.09 (586) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 18.2 (46) |

29.3 (74) |

13.2 (34) |

8.3 (21) |

1.0 (2.5) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1.6 (4.1) |

5.2 (13) |

20.0 (51) |

97.1 (247) |

| Source: The Western Regional Climate Center[25] | |||||||||||||

Cities and regions

While the Mojave Desert is generally sparsely populated, it has increasingly become urbanized in recent years.[8][2] The metropolitan areas include Las Vegas, the largest urban area in the Mojave and the largest urban area in Nevada with a population of about 2.3 million.[26] St. George, Utah, is the northeasternmost metropolitan area in the Mojave, with a population of around 180,000 in 2020, and is located at the convergence of the Mojave, Great Basin, and Colorado Plateau. The Los Angeles exurban area of Lancaster-Palmdale has more than 400,000 residents, and the Victorville area to its east has more than 300,000 residents.[8] Smaller cities or micropolitan areas in the Mojave Desert include Helendale, Lake Havasu City, Kingman, Laughlin, Bullhead City and Pahrump. All have experienced rapid population growth since 1990. The California portion of the desert also contains Edwards Air Force Base and Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake, noted for experimental aviation and weapons projects.[27][28]

The Mojave Desert has several ghost towns. The most significant are the silver and copper-mining town of Calico, California, and the old railroad depot of Kelso, California. Some of the other ghost towns are more modern, created when U.S. Route 66 (and the lesser-known U.S. Route 91) was abandoned in favor of the construction of Interstates. CA SR 14, Interstate 15, Interstate 40, CA SR 58, CA SR 138, US Route 95, and US Route 395 are the main highways that traverse the Mojave Desert.[29]

Geology

The exposed geology of the Death Valley presents a diverse and complex set of at least 23 formations of sedimentary units, two major gaps in the geologic record called unconformities, and at least one distinct set of related formations geologists call a group. The oldest rocks in the area that now includes Death Valley National Park are extensively metamorphosed by intense heat and pressure and are at least 1700 million years old. These rocks were intruded by a mass of granite 1400 Ma (million years ago) and later uplifted and exposed to nearly 500 million years of erosion.[30]: 631

The rock that forms the Mojave Desert was created under shallow water in the Precambrian,[13]: 21 [10]: 115 forming thick sequences of conglomerate, mudstone, and carbonate rock topped by stromatolites, and possibly glacial deposits from the hypothesized Snowball Earth event.[31]: 44 Rifting thinned huge roughly linear parts of the supercontinent Rodinia enough to allow sea water to invade and divide its landmass into component continents separated by narrow straits.[30]: 632 A passive margin developed on the edges of these new seas in the Death Valley region.[30]: 634 Carbonate banks formed on this part of the two margins only to be subsided as the continental crust thinned until it broke, giving birth to a new ocean basin. An accretion wedge of clastic sediment then started to accumulate at the base of the submerged precipice, entombing the region's first known fossils of complex life.

During the Paleozoic era, the area that is now the Mojave was again likely submerged under a greater sea.[10]: 116 The passive margin switched to active margin in the early-to-mid Mesozoic when the Farallon Plate under the Pacific Ocean started to dive below the North American Plate, initiating a subduction zone; volcanoes and uplifting mountains were produced as a result.[30]: 635 Erosion over many millions of years formed a relatively featureless plain.

Stretching of the crust under western North America started around 16 Ma and is thought to be caused by upwelling from the subducted spreading-zone of the Farallon Plate. This process continues into the present and is thought to be responsible for producing the Basin and Range province. By 2 to 3 million years ago this province had spread to the Death Valley area, ripping it apart and giving birth to Death Valley, Panamint Valley and surrounding ranges. These valleys partially filled with sediment and, during colder periods during the current ice age, with lakes. Lake Manly was the largest of these lakes; it filled Death Valley during each glacial period from 240,000 years ago to 10,000 years ago. By 10,500 years ago these lakes were increasingly cut off from glacial melt from the Sierra Nevada, starving them of water and concentrating salts and minerals. The desert environment seen today developed after these lakes dried up.

The Mojave Desert is a source of various minerals and metallic materials. Due to the climate, there is an accumulation of weathered bedrock, fine sand and silt, both sand and silt sediments becoming converted into colluvium.[32] The deposits of gold, tungsten, and silver have been mined frequently prior to the Second World War.[10]: 124 Additionally, there have been deposits of copper, tin, lead-zinc, manganese, iron, and various radioactive substances but they have not been mined for commercial use.[10]: 124

Ecology

Flora

The flora of the Mojave Desert consists of various endemic plant species, notably the Joshua Tree, which is a notable endemic and indicator species of the desert. There is more endemic flora in the Mojave Desert than almost anywhere in the world.[2] Mojave Desert flora is not a vegetation type, although the plants in the area have evolved in isolation because of the physical barriers of the Sierra Nevadas and the Colorado Plateau. Predominant plants of the Mojave Desert include all-scale (Atriplex polycarpa), creosote bush (Larrea tridentata), brittlebush (Encelia farinosa), desert holly (Atriplex hymenelytra), white burrobush (Hymenoclea salsola), and most notably, the Joshua tree (Yucca brevifolia). Additionally, the Mojave Desert is also home to various species of cacti, such as silver cholla (Cylindropuntia echinocarpa), Mojave prickly pear (O. erinacea), beavertail cactus (O. basilaris), and many-headed barrel cactus (Echinocactus polycephalus). Less common but distinctive plants of the Mojave Desert include ironwood (Olneya tesota), blue Palo Verde (Parkinsonia Florida), chuparosa (Justicia californica), spiny menodora (Menodora spinescens), desert senna (Cassia armata), California dalea (Psorothamnus arborescens), and goldenhead (Acamptopappus shockleyi). The Mojave Desert is generally abundant in winter annuals.[13]: 11 The plants of the Mojave Desert each generally correspond to an individual geographic feature. As such, there are distinctive flora communities within the desert.[33]

- A depiction of cassia armata, which is particularly characteristic of the Mojave

- California Dalea, an indicator species of the Mojave Desert

- Goldenhead (Acamptopappus shockleyi) an indicator species of the Mojave

- Silver cholla (Opuntia echinocarpa), a common species of cacti in the Mojave

- A creosote bush, which is common in the Mojave

Fauna

Notable species of the Mojave Desert include bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis), mountain lions (Puma concolor), black-tailed jackrabbits (Lepus californicus), and desert tortoises (Gopherus agassizii).[2] Various other species are particularly common in the Mojave Desert, such as the LeConte's thrasher (Toxostoma lecontei), banded gecko (Coleonyx variegatus), desert iguana (Dipsosaurus dorsalis), chuckwalla (Sauromalus obesus), and regal horned lizard (Phrynosoma solare).[2] Species of snake include the rosy boa (Lichanura trivirgata), Western patch-nosed snake (Salvadora hexalepis), and Mojave rattlesnake (Crotalus scutulatus).[2] These species can also occur in the neighboring Sonoran and Great Basin deserts.

The animal species of the Mojave Desert have generally fewer endemics than its flora. However, endemic fauna of the Mojave Desert include Kelso Dunes jerusalem cricket (Ammopelmatus kelsoensis), the Kelso Dunes shieldback katydid (Eremopedes kelsoensis), the Mohave ground squirrel (Spermophilus Mohavensis) and Amargosa vole (Microtus californicus scirpensis).[34] The Mojave fringe-toed lizard (Uma Scoparia) is not endemic, but almost completely limited to the Mojave Desert. There are also aquatic species that are found nowhere else,[35] such as the Devils Hole pupfish, limited to one hot spring near Death Valley.[36]

In society

History

Before the European colonization of North America, tribes of Native Americans, such as the Mohave, were hunter-gatherers living in the Mojave Desert.[37]

European explorers started exploring the deserts beginning in the 18th century. Francisco Garcés, a Franciscan friar, was the first explorer of the Mojave Desert in 1776.[38] Garcés recorded information about the original inhabitants of the deserts.

Later, as American interests expanded into California, American explorers started probing the California deserts. Jedediah Smith traveled through the Mojave Desert in 1826, finally reaching the San Gabriel Mission.[39][40]

Human development

In recent years, human development in the Mojave Desert has become increasingly present. Human development at the major urban and suburban centers of Las Vegas and Los Angeles has had an increasingly damaging effect on the wildlife of the Mojave Desert.[2] An added demand for landfill space as a result of the large metropolitan centers of Las Vegas and Los Angeles also has the real potential to drastically affect flora and fauna of the Mojave Desert. Agricultural development along the Colorado river, close to the Eastern boundary of the Mojave Desert, also causes habitat loss and degradation.[8][2] Areas that are particularly affected by human development include Ward Valley and Riverside county. The United States military also maintains installations in the Mojave Desert, making the Mojave a critical training location for the United States Department of Defense.[9] The Mojave Desert has long been a valuable resource for people, and as its human population grows, its importance will only grow. Miners, ranchers, and farmers rely on the desert for a living.[35] The Mojave is also used by the state of California to meet renewable energy objectives. Large tracts of the desert are owned by federal agencies and are leased at low cost by wind and solar energy companies, although these renewable developments can cause their own environmental impact and disturb cultural landscapes and visual resources.[41] Desert Sunlight Solar Farm, one of the largest solar farms in the world, was built approximately five miles from Joshua Tree National Park. An endangered Yuma clapper rail was found dead at the site in 2014, spurring efforts from conservation groups to protect birds from the so-called lake effect, a phenomenon in which birds can mistake the reflective glare of solar panels for a body of water.[42]

Tourism

The Mojave Desert is one of the most popular spots for tourism in North America, primarily because of the international destination of Las Vegas. The Mojave is also known for its scenery, playing host to Death Valley National Park, Joshua Tree National Park, and the Mojave National Preserve. Lakes Mead, Mohave, and Havasu provide water sports recreation, and vast off-road areas entice off-road enthusiasts. The Mojave Desert also includes three California State Parks, the Antelope Valley California Poppy Reserve, in Lancaster, Saddleback Butte State Park, in Hi Vista and Red Rock Canyon State Park. Mojave Narrows Park, operated by San Bernardino County, is a former ranch along the Mojave River.[43]

Several attractions and natural features are in the Calico Mountains. Calico Ghost Town, in Yermo, is administered by San Bernardino County. The ghost town has several shops and attractions and inspired Walter Knott to build Knott's Berry Farm. The Bureau of Land Management also administers Rainbow Basin and Owl Canyon.

Conservation status

The Mojave Desert has a relatively stable and intact conservation status. The Mojave Desert is one of the best protected distinct ecoregions in the United States,[2] as a result of the California Desert Protection Act, which designated 69 wilderness areas and established Death Valley National Park, Joshua Tree National Park, and the Mojave National Preserve.[44] However, the southwest and central east portions of the Mojave Desert are particularly threatened as a result of off-road vehicles, increasing recreational use, human development, and agricultural grazing.[2] The World Wildlife Fund lists the Mojave Desert as relatively "stable/intact".[2]

Various habitats and regions of the Mojave Desert have been protected by statute. Notably, Joshua Tree National Park, Death Valley National Park, and the Mojave National Preserve by the California Desert Protection Act of 1994. (Pub.L. 103–433). Various other federal and state land agencies have protected regions within the Mojave Desert. These include Antelope Valley California Poppy Reserve, which protects the fields of California poppies, Mojave Trails National Monument, Desert Tortoise Natural Area, Arthur B. Ripley Desert Woodland State Park, Desert National Wildlife Refuge, Lake Mead National Recreation Area, Providence Mountains State Recreation Area, Red Cliffs National Conservation Area, Red Rock Canyon State Park, Saddleback Butte State Park, Snow Canyon State Park and Valley of Fire State Park. In 2013, the Mojave Desert was further protected from development by the Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan (DRECP), in which the Bureau of Land Management designated 4.2 million acres of public land as protected wilderness as part of the National Conservation Lands of the California Desert.[45]

Cultural significance

The Mojave Desert has served as a backdrop for a number of films. The 2010 video game Fallout: New Vegas takes place in the Mojave Desert, or "Mojave Wasteland" as it is known in its post-apocalyptic future. At least seven music videos were recorded in the Mojave Desert:

- "Say You'll Be There" by the Spice Girls[46]

- "Goodbye" by Mimi Webb[47][48]

- "Bodies" by Robbie Williams

- "Burden in My Hand" by Soundgarden

- “Breathless” by The Corrs

- "What Took You So Long?" by Emma Bunton

- "Desert Rose" by Sting

- "That Don't Impress Me Much" by Shania Twain

Photographs related to U2's 1987 album The Joshua Tree were taken in the Mojave Desert.[49]

Notes

- ^ Mean maxima and minima (i.e. the highest and lowest temperature readings during an entire month or year) calculated based on data at said location from 1991 to 2020.

- ^ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the highest and lowest temperature readings during an entire month or year) calculated based on data at said location from 1991 to 2020.

References

- ^ a b "The Atlas of Global Conservation". maps.tnc.org. Archived from the original on March 5, 2012. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Mojave desert". World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2003) [1917]. Peter Roach; James Hartmann; Jane Setter (eds.). English Pronouncing Dictionary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-3-12-539683-8.

- ^ "Mojave". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- ^ "Mojave". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Munro, P., et al. A Mojave Dictionary. Los Angeles: UCLA, 1992

- ^ "The Mojave Desert". Blue Planet Biomes.

- ^ a b c d e "Mojave Desert". Encyclopædia Britannica. March 25, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ a b "Mojave Desert". Nature. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Dibblee, TW Jr (1967). Areal geology of the western Mojave Desert, California. United States Geological Survey. doi:10.3133/pp522. Professional Paper 522.

- ^ "Mojave Indian Fact Sheet". bigorrin.org. Retrieved March 9, 2022.

- ^ "Mojave Desert Biome". Blue Planet Biomes. Retrieved July 23, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Rundel, Philip W; Gibson, Arthur C (2005). Ecological communities and processes in a Mojave Desert ecosystem. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ "Mojave River". Western Rivers Conservancy. February 2020.

- ^ Lovgren, Stefan (June 11, 2021). "Life on the Amargosa—a desert river faced with drought". National Geographic. Archived from the original on June 11, 2021.

- ^ "Weather – Mojave National Park Reserve". National Park Service.

- ^ Hereford, Richard; Webb, Robert H; Longpre, Claire I (2004). "Precipitation History of the Mojave Desert Region, 1893–2001". United States Geological Survey. Fact Sheet 117-03.

- ^ Brooks, Matthew L; Matchett, JR (2006). "Spatial and temporal patterns of wildfires in the Mojave Desert, 1980–2004". Journal of Arid Environments. 67: 148–164. Bibcode:2006JArEn..67..148B. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2006.09.027.

- ^ "NOWData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991-2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 12, 2021.

- ^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991-2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "WMO Climate Normals for LAS VEGAS/MCCARRAN, NV 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "Seasonal Temperature and Precipitation Information". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved March 24, 2013.

- ^ "Seasonal Temperature and Precipitation Information". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

- ^ "Las Vegas City, Nevada". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

- ^ "History of the Air Force Flight Test Center" (PDF). 1961. K286.69-37, IRIS Number 489391.

- ^ "Naval Air Weapons Station, China Lake". The California State Military Museum. Retrieved August 17, 2013.

- ^ "Freeways and Highways". Digital-Desert.com. Retrieved December 31, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Harris, Ann G.; Tuttle, Esther; Tuttle, Sherwood D. (1997). Geology of National Parks (5th ed.). Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7872-5353-0.

- ^ Collier, Michael (1990). An Introduction to the Geology of Death Valley. Death Valley, California: Death Valley Natural History Association. LCN 90-081612.

- ^ Persico, L.P.; McFadden, L.D.; McAuliffe, J.R.; Rittenour, T.M.; Stahlecker, T.E.; Dunn, S.B.; Brody, S.A.T. (September 30, 2021). "Late Quaternary geochronologic record of soil formation and erosion: Effects of climate change on Mojave Desert hillslopes (Nevada, USA)". Geology. 50 (1): 54–59. doi:10.1130/G49270.1. ISSN 0091-7613. S2CID 244264071.

- ^ "Section 322A Mojave Desert". Digital-Desert.com. Retrieved December 31, 2024.

- ^ Neuwald, JL (2010). "Population isolation exacerbates conservation genetic concerns in the endangered Amargosa vole, Microtus californicus scirpensis". Biological Conservation. 143 (9): 2028–2038. Bibcode:2010BCons.143.2028N. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2010.05.007.

- ^ a b "Mojave Desert". The Nature Conservancy. Retrieved October 25, 2022.

- ^ "Supplemental Finding for the Devils Hole Pupfish (Cyprinodon diabolis), within the Recovery Plan for the Endangered and Threatened Species of Ash Meadows, Nevada" (PDF). US Fish and Wildlife Service. December 2019.

- ^ "History & Culture". Mojave National Preserve. National Park Service.

- ^ "Fr. Francisco Garces". Profiles in Mojave Desert History. Digital-Desert.

- ^ Gilbert, Bil (1973). The Trailblazers. Time-Life Books. pp. 96–100, 107.

- ^ Smith, Alson J. (1965). Men Against the Mountains: Jedediah Smith and the South West Expedition of 1826–1829. New York: John Day Co.

- ^ Bernhard, Meg (November 3, 2021). "'Is this really green?' The fight over solar farms in the Mojave Desert". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Roth, Sammy (August 14, 2014). "Lawsuit over desert solar plants' bird deaths". The Desert Sun.

- ^ Aaker, Therese (July 22, 2012). "Statue Dedicated to Kemper Campbell Ranch owner, former mayor Jean DeBlasis". Victorville Press Dispatch.

- ^ Wheat, Frank (1999). California desert miracle : the fight for desert parks and wilderness. San Diego, Calif.: Sunbelt Publications. ISBN 0-932653-27-8. OCLC 39677747.

- ^ Bureau of Land Management. "National Conservation Lands of the California Desert".

- ^ Desborough, James; Patterson, Emma (September 24, 2016). "EXCLUSIVE: The Spice Girls shoot that kicked off 'girl power' and the S&M secret that nearly scuppered it all". Daily Mirror. Retrieved January 27, 2023.

- ^ @mimiwebb (May 27, 2022). "outside LA, isn't it cool?" (Tweet). Retrieved January 27, 2023 – via Twitter.

- ^ Mimi Webb (May 26, 2022). "Mimi Webb – Goodbye (Official Music Video)". Retrieved January 27, 2023 – via YouTube.

- ^ "I Love The U2 Album "The Joshua Tree", Do U2?". Desert USA. July 7, 2014. Retrieved April 10, 2023.

External links

- The Nature Explorers Mojave Desert Expedition – 1 hour 27 minute ecosystem video in July

- Mojave Desert images at bioimages.vanderbilt.edu

- Mojave Desert Catalog Project