Miguel de Cervantes

Miguel de Cervantes | |

|---|---|

![This portrait, attributed to Juan de Jáuregui,[a] is unauthenticated. No authenticated image of Cervantes exists.[1][2]](Https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/09/Cervantes_J%C3%A1uregui.jpg/220px-Cervantes_J%C3%A1uregui.jpg) This portrait, attributed to Juan de Jáuregui,[a] is unauthenticated. No authenticated image of Cervantes exists.[1][2] | |

| Born | September 29, 1547 Alcalá de Henares, Spain |

| Died | 22 April 1616 (aged 68)[3] Madrid, Spain |

| Resting place | Convent of the Barefoot Trinitarians, Madrid |

| Occupation | Soldier, tax collector, accountant, purchasing agent for Navy (writing was an avocation which did not produce much income) |

| Language | Early Modern Spanish |

| Literary movement | Renaissance literature, Mannerism, Baroque |

| Notable works | Don Quixote Entremeses Novelas ejemplares |

| Spouse | Catalina de Salazar y Palacios |

| Children | Isabel c. 1584 (illegitimate)[4] |

| Signature | |

| |

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (/sɜːrˈvæntiːz, -tɪz/ sur-VAN-teez, -tiz;[5] Spanish: [miˈɣel de θeɾˈβantes saaˈβeðɾa]; 29 September 1547 (assumed) – 22 April 1616 NS)[6] was a Spanish writer widely regarded as the greatest writer in the Spanish language and one of the world's pre-eminent novelists. He is best known for his novel Don Quixote, a work considered as the first modern novel.[7][8][9] The novel has been labelled by many well-known authors as the "best book of all time"[b] and the "best and most central work in world literature".[10][9]

Much of his life was spent in relative poverty and obscurity, which led to many of his early works being lost. Despite this, his influence and literary contribution are reflected by the fact that Spanish is often referred to as "the language of Cervantes".[11]

In 1569, Cervantes was forced to leave Spain and move to Rome, where he worked in the household of a cardinal. In 1570, he enlisted in a Spanish Navy infantry regiment, and was badly wounded at the Battle of Lepanto in October 1571 and lost the use of his left arm and hand. He served as a soldier until 1575, when he was captured by Barbary pirates; after five years in captivity, he was ransomed, and returned to Madrid.

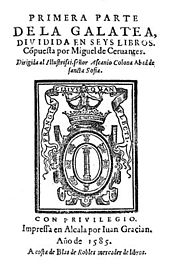

His first significant novel, titled La Galatea, was published in 1585, but he continued to work as a purchasing agent, and later as a government tax collector. Part One of Don Quixote was published in 1605, and Part Two in 1615. Other works include the 12 Novelas ejemplares (Exemplary Novels); a long poem, the Viaje del Parnaso (Journey to Parnassus); and Ocho comedias y ocho entremeses (Eight Plays and Eight Interludes). The novel Los trabajos de Persiles y Sigismunda (The Travails of Persiles and Sigismunda), was published posthumously in 1616.

The cave of Medrano (also known as the casa de Medrano) in Argamasilla de Alba, which has been known since the beginning of the 17th century, and according to the tradition of Argamasilla de Alba, was the prison of Miguel de Cervantes and the place where he conceived and began to write his famous work "Don Quixote de la Mancha".[12][13][14][15][16][17][18]

Biography

Despite his subsequent renown, much of Cervantes' life is uncertain, including his name, background and what he looked like. Although he signed himself Cerbantes, his printers used Cervantes, which became the common form. In later life, Cervantes used Saavedra, the name of a distant relative, rather than the more usual Cortinas, after his mother.[19] Historian Luce López-Baralt claimed that it comes from the word shaibedraa that in Arabic dialect means "one-handed", his nickname during his captivity.[20]

Another area of dispute is his religious background. It has been suggested that not only Cervantes' father but also his mother may have been New Christians.[21][22] Anthony Cascardi writes, "While the family might have had some claim to nobility they often found themselves in financial straits. Moreover, they may have been of converso origin, that is, converts to Catholicism of Jewish ancestry. In the Spain of Cervantes' days, this meant living under clouds of official suspicion and social mistrust, with far more limited opportunities than were enjoyed by members of the 'Old Christian' caste."[23] According to Charles D. Presberg, there is no wide following for the view that Cervantes had converso origins.[24] Cuban writer Roberto Echevarría asserts that the claims of Cervantes' converso origins are based on "very flimsy evidence", namely Cervantes' lack of social and financial progression in a time when such rewards were denied to most Spaniards regardless of social group.[25]

It is generally accepted Miguel de Cervantes was born around 29 September 1547, in Alcalá de Henares. He was the second son of barber-surgeon Rodrigo de Cervantes and his wife, Leonor de Cortinas (c. 1520–1593).[26] Rodrigo came from Córdoba, Andalusia, where his father Juan de Cervantes was an influential lawyer.

1547 to 1566: Early years

Rodrigo was frequently in debt, or searching for work, and moved constantly. Leonor came from Arganda del Rey, and died in October 1593, at the age of 73; surviving legal documents indicate she had seven children, could read and write, and was a resourceful individual with a keen eye for business. When Rodrigo was imprisoned for debt from October 1553 to April 1554, she supported the family on her own.[27]

Cervantes' siblings were Andrés (born 1543), Andrea (born 1544), Luisa (born 1546), Rodrigo (born 1550), Magdalena (born 1554) and Juan. They lived in Córdoba until 1556, when his grandfather died. For reasons that are unclear, Rodrigo did not benefit from his will and the family disappears until 1564 when he filed a lawsuit in Seville.[28]

Seville was then in the midst of an economic boom, and Rodrigo managed rented accommodation for his elder brother Andres, who was a junior magistrate. It is contended that Cervantes attended the Jesuit college in Seville, where one of the teachers was Jesuit playwright Pedro Pablo Acevedo, who moved there in 1561 from Córdoba.[29] However, legal records show his father got into debt once more and in 1566 the family moved to Madrid.[30]

1566 to 1580: Military service and captivity

In the 19th century, a biographer discovered an arrest warrant for a Miguel de Cervantes, dated 15 September 1569, who was charged with wounding Antonio de Sigura in a duel.[31] Although disputed at the time, largely on the grounds such behaviour was unworthy of so great an author, it is now accepted as the most likely reason for Cervantes leaving Madrid.[32]

He eventually made his way to Rome, where he found a position in the household of Giulio Acquaviva, an Italian bishop who spent 1568 to 1569 in Madrid, and was appointed Cardinal in 1570.[33] When the 1570 to 1573 Ottoman–Venetian War began, Spain formed part of the Holy League, a coalition formed to support the Venetian Republic. Possibly seeing an opportunity to have his arrest warrant rescinded, Cervantes went to Naples, then part of the Crown of Aragon.[34]

The military commander in Naples was Álvaro de Sande, a friend of the family, who gave Cervantes a commission in the Tercio of Sicily[35] under the Marqués de Santa Cruz. At some point, he was joined in Naples by his younger brother Rodrigo.[34] In September 1571, Cervantes sailed on board the Marquesa, part of the Holy League fleet under Don John of Austria, illegitimate half brother of Phillip II of Spain; on 7 October, they defeated the Ottoman fleet at the Battle of Lepanto.[36]

This landmark sea battle, the most significant naval conflict since the Roman Battle of Actium (32 B.C.), stopped Muslim incursion into Europe, and for the first time allowed European Christians to feel that they were not to be overrun by Islam.

According to his own account, although suffering from malaria, Cervantes was given command of a 12-man skiff, a small boat used for assaulting enemy galleys. The Marquesa lost 40 dead, and 120 wounded, including Cervantes, who received three separate wounds, two in the chest, and another that rendered his left arm useless, this last wound is the reason why he later was called "El Manco de Lepanto" (English: "The one-handed man of Lepanto", "The one-armed man of Lepanto"), a title that followed him for the rest of his life. His actions at Lepanto were a source of pride to the end of his life,[c] while Don John approved no less than four separate pay increases for him.[38]

In Journey to Parnassus, published two years before his death in 1616, Cervantes claimed to have "lost the movement of the left hand for the glory of the right".[39] As with much else, the extent of his disability is unclear, the only source being Cervantes himself, while commentators cite his habitual tendency to praise himself.[d][41] However, they were serious enough to earn him six months in the Civic Hospital at Messina, Sicily.[42]

Although he returned to service in July 1572 in the Tercio de Figueroa,[43] records show his chest wounds were still not completely healed in February 1573.[44] Based mainly in Naples, he joined expeditions to Corfu and Navarino, and took part in the 1573 occupation of Tunis and La Goulette, which were recaptured by the Ottomans in 1574.[45] Despite Lepanto, the war overall was an Ottoman victory, and the loss of Tunis a military disaster for Spain. Cervantes returned to Palermo, where he was paid off by the Duke of Sessa, who gave him letters of commendation.[46]

In early September 1575, Cervantes and Rodrigo left Naples on the galley Sol; as they approached Barcelona on 26 September, their ship was captured by Ottoman corsairs, and the brothers taken to Algiers, to be sold as slaves, or – as was the case of Cervantes and his brother – held for ransom, if this would be more lucrative than their sale as slaves.[47] Rodrigo was ransomed in 1577, but his family could not afford the fee for Cervantes, who was forced to remain.[48] Turkish historian Rasih Nuri İleri found evidence suggesting Cervantes worked on the construction of the Kılıç Ali Pasha Complex, which would mean he spent at least part of his captivity in Istanbul.[49][50][51] This is yet to be proven and no evidence has been published on the matter.[52]

By 1580, Spain was occupied with integrating Portugal, and suppressing the Dutch Revolt, while the Ottomans were at war with Persia; the two sides agreed a truce, leading to an improvement of relations.[53] After almost five years, and four escape attempts, in 1580 Cervantes was set free by the Trinitarians, a religious charity that specialised in ransoming Christian captives, and returned to Madrid.[54]

1580 to 1616: Later life and death

While Cervantes was in captivity, both Don John and the Duke of Sessa died, depriving him of two potential patrons, while the Spanish economy was in dire straits. This made finding employment difficult; other than a period in 1581 to 1582, when he was employed as an intelligence agent in North Africa, little is known of his movements prior to 1584.[55]

In April of that year, Cervantes visited Esquivias, to help arrange the affairs of his recently deceased friend and minor poet, Pedro Laínez. There he met Catalina de Salazar y Palacios (c. 1566 – 1626), eldest daughter of the widowed Catalina de Palacios; her husband died leaving only debts, but the elder Catalina owned some land of her own. This may be why in December 1584, Cervantes married her daughter, then between 15 and 18 years old.[56] The first use of the name Cervantes Saavedra appears in 1586, on documents related to their marriage.[19]

Shortly before this, his illegitimate daughter Isabel was born in November. Her mother, Ana Franca, was the wife of a Madrid innkeeper; they apparently concealed it from her husband, but Cervantes acknowledged paternity.[57] When Ana Franca died in 1598, he asked his sister Magdalena to take care of his daughter.[58]

In 1587, Cervantes was appointed as a government purchasing agent, Commissary of the Royal Galleons in Seville, obtaining wheat and oil for the doomed Spanish Armada.[59] He became a tax collector in 1592 and was briefly jailed for 'irregularities' in his accounts, but quickly released.[59] Several applications for positions in Spanish America were rejected i.e. to the Council of Indies in 1590, though modern critics note images of the colonies appear in his work.[39]

From 1596 to 1600, he lived primarily in Seville, then returned to Madrid in 1606, where he remained for the rest of his life.[60] In later years, he received some financial support from the Count of Lemos, although he was not included in the retinue Lemos took to Naples when appointed Viceroy in 1608.[39] In July 1613, he joined the Third Order Franciscans, then a common way for Catholics to gain spiritual merit.[61] It is generally accepted Cervantes died on 22 April 1616 (NS; the Gregorian calendar had superseded the Julian in 1582 in Spain and some other countries); the symptoms described, including intense thirst, correspond to diabetes, then untreatable.[62]

In accordance with his will, Cervantes was buried in the Convent of the Barefoot Trinitarians, in central Madrid.[63] His remains went missing when moved during rebuilding work at the convent in 1673, and in 2014, historian Fernando de Prado launched a project to rediscover them.[64]

In January 2015, Francisco Etxeberria, the forensic anthropologist leading the search, reported the discovery of caskets containing bone fragments, and part of a board, with the letters 'M.C.'.[65] Based on evidence of injuries suffered at Lepanto, on 17 March 2015 they were confirmed as belonging to Cervantes along with his wife and others.[66] They were formally reburied at a public ceremony in June 2015.[67]

Supposed likenesses

No authenticated portrait of Cervantes is known to exist. The one most often associated with the author is attributed to Juan de Jáuregui, but both names were added at a later date.[68] The El Greco painting in the Museo del Prado, known as Retrato de un caballero desconocido (Portrait of an Unknown Gentleman), is cited as 'possibly' depicting Cervantes, but there is no evidence for this.[69] It has been suggested that the portrait The Nobleman with his Hand on his Chest, also by El Greco, may possibly depict Cervantes.[70]

However, The Prado itself, while mentioning, in passing, that "specific names have been proposed for the sitter, including that of Cervantes",[71] and even "that the painting could be a self-portrait [of El Greco]",[71] goes on to state that "Without doubt, the most convincing suggestion has connected this figure with the Second Marquis of Montemayor, Juan de Silva y de Ribera, a contemporary of El Greco who was appointed military commander of the Alcázar in Toledo by Philip II and Chief Notary to the Crown, a position that would explain the solemn gesture of the hand, depicted in the act of taking an oath."[71]

The portrait by Luis de Madrazo, at the Biblioteca Nacional de España, painted in 1859, was based on his imagination.[72] The image that appears on Spanish euro coins of €0.10, €0.20 and €0.50 is based on a bust, created in 1905.[73]

Literary career and legacy

Cervantes claimed to have written over 20 plays, such as El trato de Argel, based on his experiences in captivity. Such works were extremely short-lived, and even Lope de Vega, the best-known playwright of the day, could not live on their proceeds.[4] In 1585, he published La Galatea, a conventional pastoral romance that received little contemporary notice; despite promising to write a sequel, he never did so.[74]

Aside from these, and some poems, by 1605, Cervantes had not been published for 20 years. In Don Quixote, he challenged a form of literature that had been a favourite for more than a century, explicitly stating his purpose was to undermine 'vain and empty' chivalric romances.[75] His portrayal of real life, and use of everyday speech in a literary context was considered innovative, and proved instantly popular. First published in January 1605, Don Quixote and Sancho Panza featured in masquerades held to celebrate the birth of Philip IV on 8 April.[58]

He finally achieved a degree of financial security, while its popularity led to demands for a sequel. In the foreword to his 1613 work, Novelas ejemplares, dedicated to his patron, the Count of Lemos, Cervantes promises to produce one, but was pre-empted by an unauthorised version published in 1614, published under the name Alonso Fernández de Avellaneda. It is possible this delay was deliberate, to ensure support from his publisher and reading public; Cervantes finally produced the second part of Don Quixote in 1615.[76]

The two parts of Don Quixote are different in focus, but similar in their clarity of prose and their realism. The first was more comic, and had greater popular appeal.[77] The second part is often considered more sophisticated and complex, with a greater depth of characterisation and philosophical insight.[78]

In addition to this, he produced a series of works between 1613 and his death in 1616. They include a collection of tales titled Exemplary Novels. This was followed by Viaje del Parnaso, Eight Comedies and Eight New Interludes, and Los trabajos de Persiles y Sigismunda, completed just before his death, and published posthumously in January 1617.

Cervantes also possessed a unique writing style, often blending elements of comedic themes to more complex adult-oriented undertones, best displayed by Don Quixote.

“In the space of a few pages, what started as an exercise in comic ridicule and, as the narrator insists on several occasions, a satirical send-up of the tales of chivalry, has taken on an entirely different dimension; it has begun to transform itself into the story of a relationship between two characters whose incompatible takes on the world are bridged by friendship, loyalty, and eventually love.”[79]

Cervantes was rediscovered by English writers in the mid-18th century. The literary editor John Bowle argued that Cervantes was as significant as any of the Greek and Roman authors then popular, and published an annotated edition in 1781. Now viewed as a significant work, at the time it proved a failure.[80] However, Don Quixote has been translated into all major languages, in 700 editions. Mexican author Carlos Fuentes suggested that Cervantes and his contemporary William Shakespeare form part of a narrative tradition that includes Homer, Dante, Defoe, Dickens, Balzac, and Joyce.[81]

Sigmund Freud claimed he learnt Spanish to read Cervantes in the original; he particularly admired The Dialogue of the Dogs (El coloquio de los perros), from Exemplary Tales, in which two dogs, Cipión and Berganza, share their stories; as one talks, the other listens, occasionally making comments. From 1871 to 1881, Freud and his close friend Eduard Silberstein wrote letters to each other, using the pen names Cipión and Berganza.[82]

In 1905, the tricentennial of the publication of Don Quixote was marked with celebrations in Spain;[83] the 400th anniversary of his death in 2016, saw the production of Cervantina, a celebration of his plays by the Compañía Nacional de Teatro Clásico in Madrid.[84] Man of La Mancha, the 1965 musical, was loosely based on Cervantes' life.[85][86] The Miguel de Cervantes Virtual Library, is the world's largest digital archive of Spanish-language historical and literary works.

Works

As listed in Complete Works of Miguel de Cervantes:[87]

- La Galatea (1585);

- El ingenioso hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha (1605): First volume of Don Quixote.

- Novelas ejemplares (1613): a collection of 12 short stories of varied types about the social, political, and historical problems of Cervantes's Spain:

- "La gitanilla" ("The Gypsy Girl")

- "El amante liberal" ("The Generous Lover")

- "Rinconete y Cortadillo" ("Rinconete & Cortadillo")

- "La española inglesa" ("The English Spanish Lady")

- "El licenciado Vidriera" ("The Lawyer of Glass")

- "La fuerza de la sangre" ("The Power of Blood")

- "El celoso extremeño" ("The Jealous Man from Extremadura")[88]

- "La ilustre fregona" ("The Illustrious Kitchen-Maid")

- "Novela de las dos doncellas" ("The Novel of the Two Damsels")

- "Novela de la señora Cornelia" ("The Novel of Lady Cornelia")

- "Novela del casamiento engañoso" ("The Novel of the Deceitful Marriage")

- "El coloquio de los perros" ("The Dialogue of the Dogs")

- Segunda Parte del Ingenioso Cavallero [sic] Don Quixote de la Mancha (1615): Second volume of Don Quixote.

- Los trabajos de Persiles y Sigismunda (1617).

Other works

Cervantes is generally considered a mediocre poet; few of his poems survive. Some appear in La Galatea, while he also wrote Dos Canciones à la Armada Invencible.

His sonnets include Al Túmulo del Rey Felipe en Sevilla, Canto de Calíope and Epístola a Mateo Vázquez. Viaje del Parnaso, or Journey to Parnassus, is his most ambitious verse work, an allegory that consists largely of reviews of contemporary poets.

He published a number of dramatic works, including ten extant full-length plays:

- Trato de Argel; based on his own experiences, deals with the life of Christian slaves in Algiers;

- La Numancia; intended as a patriotic work, dramatization of the long and brutal siege of Numantia, by Scipio Aemilianus, completing the transformation of the Iberian Peninsula into the Roman province Hispania, or España.

- El gallardo español,[89]

- Los baños de Argel,[90]

- La gran sultana, Doña Catalina de Oviedo,[91]

- La casa de los celos,[92]

- El laberinto de amor,[93]

- La entretenida,[94]

- El rufián dichoso,[95]

- Pedro de Urdemalas,[96] a sensitive play about a picaro, who joins a group of Gypsies for love of a girl.

He also wrote eight short farces (entremeses):

- El juez de los divorcios,[97]

- El rufián viudo llamado Trampagos,[98]

- La elección de los Alcaldes de Daganzo,[99]

- La guarda cuidadosa[100] (The Vigilant Sentinel),[100]

- El vizcaíno fingido,[101]

- El retablo de las maravillas,[102]

- La cueva de Salamanca

- El viejo celoso[103] (The Jealous Old Man).

These plays and short farces, except for Trato de Argel and La Numancia, made up Ocho Comedias y ocho entreméses nuevos, nunca representados[104] (Eight Comedies and Eight New Interludes, Never Before Performed), which appeared in 1615.[105] The dates and order of composition of Cervantes's short farces are unknown. Faithful to the spirit of Lope de Rueda, Cervantes endowed them with novelistic elements, such as simplified plot, the type of descriptions normally associated with a novel, and character development. Cervantes included some of his dramas among the works he was most satisfied with.

Influence

Places

- Cervantes. A municipality in the province of Lugo, Galicia, Spain, but the name of the town is not based on Miguel de Cervantes (nor is there any evidence tying him or his family to this town).

- Cervantes. A municipality in the province of Ilocos Sur, Philippines.

- Cervantes. A township situated north of the Western Australian state capital Perth in Australia.

Television

- Cervantes is a recurring character in the Spanish television show El ministerio del tiempo, portrayed by actor Pere Ponce.

- Cervantes played a prominent role in the episode "Gentlemen of Spain" of the TV series Sir Francis Drake (1961–1962). He was portrayed by the actor Nigel Davenport and the plot had him heroically rescuing other Christian captives from the Barbary pirates.

See also

- Casa de Cervantes

- Instituto Cervantes

- Miguel de Cervantes Prize

- Miguel de Cervantes European University

- Miguel de Cervantes Health Care Centre

- Miguel de Cervantes High School

- Miguel de Cervantes Memorial

- Miguel de Cervantes University

Notes

- ^ Although Cervantes wrote in his preface to Exemplary Novels that Jáuregui did paint his portrait: "el cual amigo bien pudiera, como es uso y costubre, grabarme y esculpirme en la primera hoja de este libro, pues le diera mi retrato el famoso D. Juan de Jauregui".

- ^ Milan Kundera, John le Carré, John Irving,[9] Doris Lessing, Salman Rushdie, Miriam Lebwohl, Nadine Gordimer, Wole Soyinka, Seamus Heaney, Carlos Fuentes, Norman Mailer, and Astrid Lindgren[10] were among the authors polled.

- ^ In the Preface to Volume 2 of Don Quixote, he writes "the loss of my hand (came about) on the grandest occasion the past or present has seen, or the future can hope to see. If my wounds have no beauty to the beholder's eye, they are, at least, honorable in the estimation of those who know where they were received".[37]

- ^ According to scholar Nicolás Marín: "No hay ocasión en que Cervantes no se elogie, bien que excusándose por salir de los límites de su natural modestia; tantas veces ocurre esto que no es posible verla nunca ni creer en ella". [There is no occasion in which Cervantes does not praise himself, even if he excuses himself for going beyond the limits of his natural modesty; this happens so many times that it is never possible to see it or believe in it].[40]

References

- ^ Chacón y Calvo, José María (1947–1948). "Retratos de Cervantes". Anales de la Academia Nacional de Artes y Letras (in Spanish). 27: 5–17.

- ^ Ferrari, Enrique Lafuente (1948). La novela ejemplar de los retratos de Cervantes (in Spanish).

- ^ Armstrong, Richard. "Time Out of Joint". Engines of Our Ingenuity. Lienhard, John (host, producer). Retrieved 9 December 2019 – via UH.edu.

- ^ a b McCrory 2006, p. 112.

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). "Cervantes". Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- ^ de Riquer Morera, Martín. "Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra". Diccionario biográfico España (in Spanish). Real Academia de la Historia.

- ^ Bloom, Harold (13 December 2003). "The knight in the mirror". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- ^ Puchau de Lecea, Ana; Pérez de León, Vicente (25 June 2018). "Guide to the classics: Don Quixote, the world's first modern novel – and one of the best". The Conversation. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ a b c "Don Quixote gets authors' votes". BBC News. 7 May 2002. Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- ^ a b Chrisafis, Angelique (21 July 2003). "Don Quixote is the world's best book say the world's top authors". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ^ Diego, Gerardo. "La lengua de Cervantes" (PDF) (in Spanish). Ministerio de la Presidencia de España. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 October 2008. Retrieved 14 September 2008.

- ^ "Casa – Cueva de Medrano - Ruta del Vino de La Mancha" (in European Spanish). 6 January 2022. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ "Visita Museo Casa de Medrano | TCLM". www.turismocastillalamancha.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 13 September 2024.

- ^ "Casa de Medrano". Turismo Argamasilla de Alba (in Spanish). Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ "CERVANTES en la BNE - Casa de Medrano que sirvió de prisión a Cervantes en Argamasilla de Alba". cervantes.bne.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ "Cueva Prisión de Medrano | Portal de Cultura de Castilla-La Mancha". cultura.castillalamancha.es. Retrieved 13 September 2024.

- ^ "Cueva Prisión de Medrano (Argamasilla de Alba). Turismo Ciudad Real". Turismo Ciudad Real (in Spanish). Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ "Cueva de Medrano: leyenda y realidad del origen del Quijote". www.lanzadigital.com (in Spanish). 27 April 2019. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ a b Garcés 2002, p. 189.

- ^ Iglesias, Amalia (17 November 2016). "Luce López-Baralt: "Ante el 'Quijote' y San Juan de la Cruz siento el vértigo de asomarme a un abismo sin fin"". abc (in Spanish).

- ^ Byron 1978, p. 32.

- ^ Lokos 2016, p. 116.

- ^ Cascardi 2002, p. 4.

- ^ Presberg, Charles D. (2018). "Chapter 5: Anatomy of Contemporary Cervantes Studies: A Romance of "Two Cities"". In Cruz, Anne J.; Johnson, Carrol B. (eds.). Cervantes and His Postmodern Constituencies. Taylor & Francis. p. 89. ISBN 978-1-317-94451-5. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

Though the thesis of Cervantes, converso, has yet to gain a wide following among Cervantes scholars, El pensamiento stood as the sponsoring text for most criticism on Cervantes, whose other writings were judged in relation to Don Quixote, for over fifty years.

- ^ Echevarria, Roberto G. (2010). "Introduction". Cervantes' Don Quixote: A Casebook. Casebooks in Criticism. Oxford University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-19-996046-0. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ McCrory 2006, p. 35.

- ^ McCrory 2006, p. 34.

- ^ McCrory 2006, p. 36.

- ^ Egginton 2016, p. 23.

- ^ McCrory 2006, pp. 40–41.

- ^ McCrory 2006, p. 48.

- ^ Lokos 2016, p. 118.

- ^ McCrory 2006, p. 50.

- ^ a b McCrory 2006, p. 52.

- ^ "Military honours for Miguel de Cervantes". Gobierno de España. Ministerio de Defensa. 16 June 2015. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ Davis 1999, p. 199.

- ^ Cervantes 1615, p. 20.

- ^ McCrory 2006, p. 58.

- ^ a b c Ma 2017, p. 99.

- ^ Marín, Nicolás (1973). "Belardo furioso. Una de Lope mal leída". Anales Cervantinos. 12: 21. ISSN 0569-9878 – via Cervantes Virtual.

- ^ Eisenberg 1996, pp. 32–53.

- ^ Fitzmaurice-Kelly 1892, p. 33.

- ^ "La Tumba de Cervantes y El "Tercio Viejo de Sicilia."". Ejercito de Tierra (in Spanish). Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ McCrory 2006, p. 60.

- ^ Garcés 2002, pp. 191–192, 220.

- ^ McCrory 2006, p. 63.

- ^ Fitzmaurice-Kelly 1892, p. 41.

- ^ McCrory 2006, pp. 65–68, 78.

- ^ Eren, Güleren (June 2006). "The Heritage of a Sailor". Beyoğlu. No. 3. pp. 59–64.

- ^ Bayrak, M. Orhan (1994). Türkiye Tarihi Yerler Kılavuzu (in Spanish). İstanbul: İnkılâp Kitabevi. pp. 326–327. ISBN 975-10-0705-4.

- ^ Sumner-Boyd, Hilary; Freely, John (1994). Strolling Through Istanbul: A Guide to the City (6 ed.). İstanbul: SEV Matbaacılık. pp. 450–451. ISBN 975-8176-44-7.

- ^ Vielva Diego, Héctor (September 2016). "Cervantes in Istanbul, history or fiction?" (PDF). Archivo de la Frontera (in Spanish). ISBN 978-84-690-5859-6. Retrieved 12 December 2023.

- ^ Glete 2001, p. 84.

- ^ Parker & Parker 2009, p. ?.

- ^ McCrory 2006, pp. 100–101.

- ^ McCrory 2006, pp. 115–116.

- ^ McCrory 2006, p. 113.

- ^ a b McCrory 2006, p. 206.

- ^ a b Cascardi 2002, p. 6.

- ^ Close 2008, p. 12.

- ^ Fitzmaurice-Kelly 1892, p. 179.

- ^ McCrory 2006, p. 264.

- ^ "Miguel de Cervantes Biography – life, family, children, name, story, death, history, wife, son, book". Notablebiographies.com. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- ^ Tremlett, Giles (25 July 2011). "Madrid begins search for bones of Don Quixote author Miguel de Cervantes | Books". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ "Casket find could lead to remains of Don Quixote author Miguel de Cervantes | Books". The Guardian. Agence France-Presse. 27 January 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ "Spain finds Don Quixote writer Cervantes' tomb in Madrid". BBC News. 17 March 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ Giles, Ciaran (11 June 2015). "Spain formally buries Cervantes, 400 years later". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 13 June 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ^ Byron 1978, p. 131.

- ^ "Portrait of a Gentleman". Museo del Prado (in Spanish). Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte, Gobierno de España. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ "Portrait of a Nobleman with his Hand on his Chest | artehistoria.com". www.artehistoria.com. Archived from the original on 12 December 2022. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

- ^ a b c Ruiz, L. (2008). "El caballero de la mano en el pecho" En: El retrato del Renacimiento, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado, pp. 326-327. Museo del Prado. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

- ^ "Programa Europa – Cervantes". Fábrica Nacional de Moneda y Timbre (in Spanish). Real Casa de la Moneda. 2013. Archived from the original on 29 June 2013. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ "Euro notes and coins: national sides". European Commission. 8 January 2010. Archived from the original on 7 February 2010. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ McCrory 2006, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Close 2008, p. 39.

- ^ McCrory 2006, pp. 234–235.

- ^ Mitsuo & Cullen 2006, pp. 148–152.

- ^ Putnam 1976, p. 14.

- ^ Sept 29, Bret McCabe / Published; 2016 (29 September 2016). "The remarkable life of Miguel de Cervantes and how it shaped his timeless tale, 'Don Quixote'". The Hub. Retrieved 16 January 2025.

{{cite web}}:|last2=has numeric name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Truman 2003, pp. 9–31.

- ^ Fuentes 1988, p. 69–70.

- ^ Riley 1994, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Leerssen, J.; Rigney, A. (2014). Commemorating Writers in Nineteenth-Century Europe: Nation-Building and Centenary Fever. Springer. p. 207. ISBN 978-1-137-41214-0.

- ^ "Cervantina de Compañía Nacional de Teatro Clásico y Ron Lalá". www.centroculturalmva.es (in Spanish). 19 April 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ "Don Quixote as Theatre, Cervantes". Journal of the Cervantes Society of America. 19 (1): 125–130. 1999. doi:10.3138/Cervantes.19.1.125. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ^ "A Diary for I, Don Quixote, Cervantes" (PDF). Journal of the Cervantes Society of America. 21 (2): 117–123. 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ^ Sevilla Arroyo, Florencio; Rey Hazas, Antonio, eds. (1995). OBRAS COMPLETAS de Miguel de Cervantes [Complete Works of Miguel de Cervantes]. Centro de Estudios Cervantinos – via Proyecto Cervantes, Texas A&M University.

- ^ Riley, Edward C.; Cruz, Anne J., Miguel de Cervantes at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ "Comedia Famosa del Gallardo Español". Página de inicio del web de Cervantes (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ "Los Baños de Argel" (PDF). miguelde.cervantes.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 August 2020. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- ^ "La Gran Sultana" (PDF). miguelde.cervantes.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 November 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ "La casa" (PDF). miguelde.cervantes.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 November 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ "El Laberinto" (PDF). miguelde.cervantes.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ "La Entretenida" (PDF). miguelde.cervantes.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ "Ocho comedias y ocho entremeses / El rufian dichoso". cervantes.tamu.edu. Archived from the original on 9 June 2010.

- ^ "Pedro Urdamles" (PDF). miguelde.cervantes.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 August 2020. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ "Entremes: el Juez de los Divorcios". cervantes.uah.es (in Spanish).

- ^ "El Rufián Viudo Llamado Trampagos". comedias.org (in Spanish).

- ^ "Daganzo" (PDF). miguelde.cervantes.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 April 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ a b "Info" (PDF). biblioteca.org.ar. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ "Entremes: Del Vizcaíno Fingido". cervantes.uah.es.

- ^ "Entremes: Del Retablo de las Maravillas". cervantes.uah.es.

- ^ "Entremes: Del Viejo Celoso". cervantes.uah.es.

- ^ "Ocho comedias y ocho entremeses". cervantes.tamu.edu. Archived from the original on 5 January 2010.

- ^ "Ocho comedias, y ocho entremeses nuevos | work by Cervantes". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

Bibliography

- Byron, William (1978). Cervantes; A Biography. London: Cassell. ISBN 978-1-55778-006-5.

- Cascardi, Anthony J., ed. (17 October 2002). The Cambridge Companion to Cervantes. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52166-387-8.

- Cervantes, Miguel de (1615). The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha. Translated by Ormsby, John (2015 ed.). Aegitas. ISBN 978-5-00064-159-0.

- Close, A. J. (2008). A Companion to Don Quixote. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85566-170-7.

- Davis, Paul K. (1999). 100 Decisive Battles: From Ancient Times to the Present. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19514-366-9.

- Egginton, William (2016). The Man Who Invented Fiction: How Cervantes Ushered in the Modern World. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-62040-175-0.

- Eisenberg, Daniel (1996). "Cervantes, autor de la "Topografía e historia general de Argel" publicada por Diego de Haedo". Cervantes: Bulletin of the Cervantes Society of America. 16 (1): 32–53. doi:10.3138/Cervantes.16.1.032. S2CID 187065952.

- Fitzmaurice-Kelly, James (1892). The Life of Cervantes. Chapman Hall.

- Fuentes, Carlos (1988). Myself with Others: Selected Essays. Farrar Straus Giroux. ISBN 978-0-37421-750-1.

- Garcés, Maria Antonia (2002). Cervantes in Algiers: A Captive's Tale. Vanderbilt University Press. ISBN 978-0-82651-406-6.

- Glete, Jan (2001). War and the State in Early Modern Europe: Spain, the Dutch Republic and Sweden as Fiscal-Military States (Warfare and History). Routledge. ISBN 978-0-41522-644-8.

- Lokos, Ellen (2016). Cruz, Anne J; Johnson, Carroll B (eds.). The Politics of Identity and the Enigma of Cervantine Genealogy in Cervantes and His Postmodern Constituencies. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-13886-441-2.

- Ma, Ning (2017). The Age of Silver: The Rise of the Novel, East and West. OUP. ISBN 978-0-19060-656-5.

- McCrory, Donald P. (2006). No Ordinary Man: The Life and Times of Miguel de Cervantes. Dover Publishing. ISBN 978-0-48645-361-3.

- Mitsuo, Nakamura; Cullen, Jennifer (December 2006). "On 'Don Quixote'". Review of Japanese Culture and Society. 18 (East and West): 147–156. JSTOR 42800232.

- Parker, Barbara Keevil; Parker, Duane F. (2009). Miguel de Cervantes. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-43810-685-4.

- Putnam, Samuel (1976). Introduction to The Portable Cervantes. Harmondsworth: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14015-057-5.

- Riley, E. C. (1994). "Cipión" Writes to "Berganza" in the Freudian Academia Española". Cervantes: Bulletin of the Cervantes Society of America. 14 (1): 3–18. doi:10.3138/cervantes.14.1.003. S2CID 193117593.

- Truman, R. W. (2003). "The Rev. John Bowle's Quixotic Woes Further Explored". Cervantes: Bulletin of the Cervantes Society of America. 23 (1): 9–43. doi:10.3138/Cervantes.23.2.009. S2CID 190575135.

Further reading

- Bloom, Harold (ed.) 2001. Cervantes's Don Quixote (Modern Critical Interpretations).

- Bloom, Harold (ed.) 2005. Miguel de Cervantes (Modern Critical Views).

- Cervantes, Miguel de (1613). Novelas ejemplares [The Exemplary Novels of Cervantes]. Translated by Kelly, Walter K. (2017 ed.). Pinnacle Books. ISBN 978-1374957275.

- Eisenberg, Daniel (2004). "La supuesta homosexualidad de Cervantes". Siglos dorados : homenaje a Augustin Redondo. Vol. 1. Madrid: Castalia. ISBN 84-9740-100-X.

- El Saffar, Ruth S. (ed.) 1986. Critical Essays on Cervantes. Boston: G. K. Hall.

- González Echevarría, Roberto (ed.) 2005. Cervantes' Don Quixote: A Casebook.

- Nelson, Lowry 1969. Cervantes: A Collection of Critical Essays. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

- Pérez, Rolando (2016). "What is Don Quijote/Don Quixote And…And…And the Disjunctive Synthesis of Cervantes and Kathy Acker." Cervantes ilimitado: cuatrocientos años del Quijote. Ed. Nuria Morgado. ALDEEU. 75–100.

- Pérez, Rolando (2021). "Cervantes’s “Republic”: On Representation, Imitation, and Unreason". eHumanista 47: 89-111.

- Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel and Willi Glasauer (1988). Scenes from World Literature and Portraits of Greatest Authors, Círculo de Lectores.

- Weber, Olivier, Flammarion (2011). Le Barbaresque.

External links

- Works by Miguel de Cervantes in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by or about Miguel de Cervantes at the Internet Archive

- Works by Miguel de Cervantes at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Giles, Ciaran (11 June 2015). "Spain formally buries Cervantes, 400 years later". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 13 June 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- "Casket find could lead to remains of Don Quixote author Miguel de Cervantes | Books". The Guardian. Agence France-Presse. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- "Euro notes and coins: national sides". European Commission. 8 January 2010. Archived from the original on 7 February 2010. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- "Portrait of a Gentleman". Museo del Prado (in Spanish). Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte, Gobierno de España. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes Spanish web site with multiple Cervantes links and audio of whole of Don Quixote

- Famous Hispanics

- The Cervantes Project Archived 1 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine with biographies and chronology

- Information about Miguel de Cervantes

- Cervantine Collection of the Biblioteca de Catalunya Archived 12 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- Miguel de Cervantes (1547–1616): Life and Portrait Archived 12 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine The Cervantes Project. Canavaggio, Jean.

- Cervantes's Birthplace Museum Archived 7 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- Miguel de Cervantes Collection From the Rare Book and Special Collection Division at the Library of Congress

- Cervantes chatbot in Spanish