Kingdom of Kush

Kingdom of Kush | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 780 BC – c. AD 350[2] | |||||||||||||||

![Kushite heartland, and Kushite Empire of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt, circa 700 BC.[3]](Https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/07/Kushite_heartland_and_Kushite_Empire_of_the_25th_dynasty_circa_700_BCE.jpg/250px-Kushite_heartland_and_Kushite_Empire_of_the_25th_dynasty_circa_700_BCE.jpg) Kushite heartland, and Kushite Empire of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt, circa 700 BC.[3] | |||||||||||||||

| Status | Independent (780 BC – 330 AD) Under Aksumite rule (330 AD – 350 AD) | ||||||||||||||

| Capital | Kerma Napata Meroë | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Meroitic Egyptian[4] Blemmyan[5] Old Nubian | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Kushite religion[6] Kushite polytheism Ancient Egyptian religion | ||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Kushite | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Bronze Age to Late Antiquity | ||||||||||||||

• Established | c. 780 BC | ||||||||||||||

• Capital moved to Meroe | 591 BC | ||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | c. AD 350[2] | ||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||

• Meroite phase[7] | 1,150,000 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Sudan Egypt | ||||||||||||||

The Kingdom of Kush (/kʊʃ, kʌʃ/; Egyptian: 𓎡𓄿𓈙𓈉 kꜣš, Assyrian: ![]() Kûsi, in LXX Χους or Αἰθιοπία; Coptic: ⲉϭⲱϣ Ecōš; Hebrew: כּוּשׁ Kūš), also known as the Kushite Empire, or simply Kush, was an ancient kingdom in Nubia, centered along the Nile Valley in what is now northern Sudan and southern Egypt.

Kûsi, in LXX Χους or Αἰθιοπία; Coptic: ⲉϭⲱϣ Ecōš; Hebrew: כּוּשׁ Kūš), also known as the Kushite Empire, or simply Kush, was an ancient kingdom in Nubia, centered along the Nile Valley in what is now northern Sudan and southern Egypt.

The region of Nubia was an early cradle of civilization, producing several complex societies that engaged in trade and industry.[8] The city-state of Kerma emerged as the dominant political force between 2450 and 1450 BC, controlling the Nile Valley between the first and fourth cataracts, an area as large as Egypt. The Egyptians were the first to identify Kerma as "Kush" probably from the indigenous ethnonym "Kasu", over the next several centuries the two civilizations engaged in intermittent warfare, trade, and cultural exchange.[9]

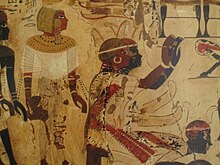

Much of Nubia came under Egyptian rule during the New Kingdom period (1550–1070 BC). Following Egypt's disintegration amid the Late Bronze Age collapse, the Kushites reestablished a kingdom in Napata (now modern Karima, Sudan). Though Kush had developed many cultural affinities with Egypt, such as the veneration of Amun, and the royal families of both kingdoms occasionally intermarried, Kushite culture, language and ethnicity was distinct; Egyptian art distinguished the people of Kush by their dress, appearance, and even method of transportation.[8]

In the 8th century BC, King Kashta ("the Kushite") peacefully became King of Upper Egypt, while his daughter, Amenirdis, was appointed as Divine Adoratrice of Amun in Thebes.[10] His successor Piye invaded Lower Egypt, establishing the Kushite-ruled Twenty-fifth Dynasty. Piye's daughter, Shepenupet II, was also appointed Divine Adoratrice of Amun. The monarchs of Kush ruled Egypt for over a century until the Assyrian conquest, being dethroned by the Assyrian kings Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal in the mid-seventh century BC. Following the severing of ties with Egypt, the Kushite imperial capital was located at Meroë, during which time it was known by the Greeks as Aethiopia.

From the third century BC to the third century AD, the northernmost part of Nubia would be invaded and annexed by Egypt. Ruled by the Macedonians and Romans for the next 600 years, this territory would be known in the Greco-Roman world as Dodekaschoinos. It was later taken back by the Kushite king Yesebokheamani. The Kingdom of Kush persisted as a major regional power until the fourth century AD when it weakened and disintegrated from internal rebellion amid worsening climatic conditions and invasions and conquest of the kingdom of Kush by the Noba people who introduced the Nubian languages and gave their name to Nubia itself. Because the Noba and the Blemmyes were at war with the Kushites, the Aksumites took advantage of this, capturing Meroë and looting its gold, marking the end of the kingdom and its dissolution into the three polities of Nobatia, Makuria and Alodia, though the Aksumite presence in Meroe was likely short lived. Sometime after this event, the Kingdom of Alodia would gain control of the southern territory of the former Meroitic empire including parts of Eritrea.[11]

Long overshadowed by its more prominent Egyptian neighbor, archaeological discoveries since the late 20th century have revealed Kush to be an advanced civilization in its own right. The Kushites had their own unique language and script; maintained a complex economy based on trade and industry; mastered archery; and developed a complex, urban society with uniquely high levels of female participation.[12]

Name

| Kush in hieroglyphs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

k3š Ku'sh | |||||

The native name of the Kingdom was recorded in Egyptian as kꜣš, likely pronounced IPA: [kuɫuʃ] or IPA: [kuʔuʃ] in Middle Egyptian, when the term was first used for Nubia, based on the New Kingdom-era Akkadian transliteration of the genitive kūsi.[13][14][15]

It is also an ethnic term for the native population who initiated the kingdom of Kush. The term is also displayed in the names of Kushite persons,[16] such as King Kashta (a transcription of kꜣš-tꜣ "(one from) the land of Kush"). Geographically, Kush referred to the region south of the first cataract in general. Kush also was the home of the rulers of the 25th Dynasty.[17]

The name Kush, since at least the time of Josephus, has been connected with the biblical character Cush, in the Hebrew Bible (Hebrew: כּוּשׁ), son of Ham (Genesis 10:6). Ham had four sons named: Cush, Put, Canaan, and Mizraim (Hebrew name for Egypt). According to the Bible, Nimrod, a son of Cush, was the founder and king of Babylon, Erech, Akkad and Calneh, in Shinar (Gen 10:10).[18] The Bible also makes reference to someone named Cush who is a Benjamite (Psalms 7:1, KJV).[19]

In Greek sources Kush was known as Kous (Κους) or Aethiopia (Αἰθιοπία).[20]

History

Prelude

(c.2500 BC–c.1550 BC)

Kerma culture (2500–1500 BC)

The Kerma culture was an early civilization centered in Kerma, Sudan. It flourished from around 2500 BC to 1500 BC in ancient Nubia. The Kerma culture was based in the southern part of Nubia, or "Upper Nubia" (in parts of present-day northern and central Sudan), and later extended its reach northward into Lower Nubia and the border of Egypt.[21] The polity seems to have been one of several Nile Valley states during the Middle Kingdom of Egypt. In the Kingdom of Kerma's latest phase, lasting from about 1700–1500 BC, it absorbed the Sudanese kingdom of Saï and became a sizable, populous empire rivaling Egypt.

Egyptian Nubia (1504–1070 BC)

Mentuhotep II, the 21st century BC founder of the Middle Kingdom, is recorded to have undertaken campaigns against Kush in the 29th and 31st years of his reign. This is the earliest Egyptian reference to Kush; the Nubian region had gone by other names in the Old Kingdom.[22] Under Thutmose I, Egypt made several campaigns south.

The Egyptians ruled Kush in the New kingdom beginning when the Egyptian King Thutmose I occupied Kush and destroyed its capital, Kerma.[23]

This eventually resulted in their annexation of Nubia c. 1504 BC. Around 1500 BC, Nubia was absorbed into the New Kingdom of Egypt, but rebellions continued for centuries. After the conquest, Kerma culture was increasingly Egyptianized, yet rebellions continued for 220 years until c. 1300 BC. Nubia nevertheless became a key province of the New Kingdom, economically, politically, and spiritually. Indeed, major pharaonic ceremonies were held at Jebel Barkal near Napata.[24] As an Egyptian colony from the 16th century BC, Nubia ("Kush") was governed by an Egyptian Viceroy of Kush.

Resistance to the early eighteenth Dynasty Egyptian rule by neighboring Kush is evidenced in the writings of Ahmose, son of Ebana, an Egyptian warrior who served under Nebpehtrya Ahmose (1539–1514 BC), Djeserkara Amenhotep I (1514–1493 BC), and Aakheperkara Thutmose I (1493–1481 BC). At the end of the Second Intermediate Period (mid-sixteenth century BC), Egypt faced the twin existential threats—the Hyksos in the North and the Kushites in the South. Taken from the autobiographical inscriptions on the walls of his tomb-chapel, the Egyptians undertook campaigns to defeat Kush and conquer Nubia under the rule of Amenhotep I (1514–1493 BC). In Ahmose's writings, the Kushites are described as archers, "Now after his Majesty had slain the Bedoin of Asia, he sailed upstream to Upper Nubia to destroy the Nubian bowmen."[25] The tomb writings contain two other references to the Nubian bowmen of Kush. By 1200 BC, Egyptian involvement in the Dongola Reach was nonexistent.

Egypt's international prestige had declined considerably towards the end of the Third Intermediate Period. Its historical allies, the inhabitants of Canaan, had fallen to the Middle Assyrian Empire (1365–1020 BC), and then the resurgent Neo-Assyrian Empire (935–605 BC). The Assyrians, from the tenth century BC onwards, had once more expanded from northern Mesopotamia, and conquered a vast empire, including the whole of the Near East, and much of Anatolia, the eastern Mediterranean, the Caucasus and early Iron Age Iran.

According to Josephus Flavius, the biblical Moses led the Egyptian army in a siege of the Kushite city of Meroe. To end the siege Princess Tharbis was given to Moses as a (diplomatic) bride, and thus the Egyptian army retreated back to Egypt.[26]

Formation (c. 1070–754 BC)

With the disintegration of the New Kingdom around 1070 BC, Kush became an independent kingdom centered at Napata in modern northern Sudan.[28] This more-Egyptianized "Kingdom of Kush" emerged, possibly from Kerma, and regained the region's independence from Egypt. The extent of cultural/political continuity between the Kerma culture and the chronologically succeeding Kingdom of Kush is difficult to determine. The latter polity began to emerge around 1000 BC, 500 years after the end of the Kingdom of Kerma.[citation needed]

The first Kushite king known by name was Alara, who ruled somewhere between 800[29] and 760 BC.[30] No contemporary inscriptions of him exist.[29] He was first mentioned in the funerary stela of his daughter Tabiry, the wife of king Piye. Later royal inscriptions remember Alara as the founder of the dynasty, some calling him "chieftain", others "king". A 7th century inscription claimed that his sister was the grandmother of king Taharqo.[31] An inscription of the 5th century king Amanineteyerike remembered Alara's reign as long and successful.[32] Alara was probably buried at el-Kurru, although there exists no inscription to identify his tomb.[29] It has been proposed that it was Alara who turned Kush from a chiefdom to an Egyptianized kingdom centered around the cult of Amun.[33]

Rule over Egypt (754 BC–656 BC)

Alara's successor Kashta extended Kushite control north to Elephantine and Thebes in Upper Egypt. Kashta's successor Piye seized control of Lower Egypt around 727 BC.[34] Piye's Victory Stela, celebrating these campaigns between 728 and 716 BC, was found in the Amun temple at Jebel Barkal. He invaded an Egypt fragmented into four kingdoms, ruled by King Peftjauawybast, King Nimlot, King Iuput II, and King Osorkon IV.[35]: 115, 120

Why the Kushites chose to enter Egypt at this crucial point of foreign domination is subject to debate. Archaeologist Timothy Kendall offers his own hypotheses, connecting it to a claim of legitimacy associated with Jebel Barkal.[37] Kendall cites the Victory Stele of Piye at Jebel Barkal, which states that "Amun of Napata granted me to be ruler of every foreign country," and "Amun in Thebes granted me to be ruler of the Black Land (Kmt)". According to Kendall, "foreign lands" in this regard seems to include Lower Egypt while "Kmt" seems to refer to a united Upper Egypt and Nubia.[37]

Piye's successor, Shabataka, defeated the Saite kings of northern Egypt between 711 and 710 BC and installed himself as king in Memphis. He then established ties with Sargon II of the Neo-Assyrian Empire.[35]: 120 After the reign of Shabaka, Pharaoh Taharqa's army undertook successful military campaigns, as attested by the "list of conquered Asiatic principalities" from the Mut temple at Karnak and "conquered peoples and countries (Libyans, Shasu nomads, Phoenicians?, Khor in Palestine)" from Sanam temple inscriptions.[38] However the regions in the southern Levant claimed by Shabataka were seen by Assyria as under their dominion, and imperial ambitions of both the Mesopotamian based Assyrian Empire and Kushite Empire made war with the 25th dynasty inevitable. In 701 BC, Taharqa and his army aided Judah and King Hezekiah in withstanding a siege by King Sennacherib of the Assyrians (2 Kings 19:9; Isaiah 37:9).[39] There are various theories (Taharqa's army,[40] disease, divine intervention, Hezekiah's surrender or agreeing to pay tribute) as to why the Assyrians failed to take the city.[41] Historian László Török mentions that Egypt's army "was beaten at Eltekeh" under Taharqa's command, but "the battle could be interpreted as a victory for the double kingdom", since Assyria did not take Jerusalem, however the Egyptian and Kushite forces withdrew to Egypt and the Assyrian king Sennacherib appears to have occupied part of the Sinai.[42]

The power of the 25th Dynasty reached a climax under Taharqa. The Nile valley empire was as large as it had been since the New Kingdom. New prosperity[16] revived Egyptian culture.[43] Religion, the arts, and architecture were restored to their glorious Old, Middle, and New Kingdom forms. The Kushite pharaohs built or restored temples and monuments throughout the Nile valley, including Memphis, Karnak, Kawa, and Jebel Barkal.[44][45] It was during the 25th dynasty that the Nile valley saw the first widespread construction of pyramids (many in modern Sudan) since the Middle Kingdom.[46][47][48] The Kushites developed their own script, the Meroitic alphabet, which was influenced by Egyptian writing systems c. 700–600 BC, although it appears to have been wholly confined to the royal court and major temples.[49]

Assyrian conquest of Egypt

Taharqa and his Judean allies initially defeated the Assyrians at Ashkelon when war broke out in 674 BC.[citation needed] The relatively small Assyrian force had first defeafed Canaanite and Arab tribes in the region and then immediately marched at great speed on Ashkelon, leaving them exhausted.[citation needed] However, in 671 BC, the Assyrian King Esarhaddon started the Assyrian conquest of Egypt with a larger and better prepared force. The Assyrians advanced rapidly and decisively. Memphis was taken, and Taharqa fled to Nubia, while his heir and other family members were taken to the Assyrian capital Nineveh as prisoners. Esarhaddon boasted how he "deported all Aethiopians from Egypt, leaving not one to pay homage to me" However, the native Egyptian vassal rulers installed by Esarhaddon as puppets were unable to effectively retain full control of the entire country, and Taharqa was able to regain control of Memphis. Esarhaddon's 669 BC campaign to once more eject Taharqa was abandoned when Esarhaddon died in Harran on the way to Egypt, leaving Esarhaddon's successor, Ashurbanipal the task. He defeated Taharqa, driving his forces back into Nubia, and Taharqa died in Napata soon after in 664 BC.[35]: 121

Taharqa's successor, Tantamani sailed north from Napata, through Elephantine, and to Thebes with a large army, where he was "ritually installed as the king of Egypt."[50] From Thebes, Tantamani began his attempt at reconquest[50] and regained control of a part of southern Egypt as far as Memphis from the native Egyptian puppet rulers installed by the Assyrians.[51] Tantamani's dream stele states that he restored order from the chaos, where royal temples and cults were not being maintained.[50] After defeating Sais and killing Assyria's vassal, Necho I, in Memphis, "some local dynasts formally surrendered, while others withdrew to their fortresses."[50]: 185 Tantamani proceeded north of Memphis, invading Lower Egypt and, besieged cities in the Delta, a number of which surrendered to him.[citation needed] The Assyrians, who had maintained only a small military presence in the north, then sent a large army southwards in 663 BC. Tantamani was decisively routed, and the Assyrian army sacked Thebes to such an extent it never truly recovered. Tantamani was chased back to Nubia, but he continued to try and assert control over Upper Egypt until c. 656 BC. At this date, a native Egyptian ruler, Psamtik I son of Necho, placed on the throne as a vassal of Ashurbanipal, took control of Thebes.[16][52] The last links between Kush and Upper Egypt were severed after hostilities with the Saite kings in the 590s BC.[35]: 121–122

Napatan period (656 BC–c. 270 BC)

Kushite civilization continued for several centuries. According to Welsby, "throughout the Saite, Persian, Ptolemaic, and Roman periods, the Kushite rulers—the descendants of the XXVth Dynasty pharaohs, and the guardians of the Temple of Amun at Jebel Barkal[53]—could have pressed their 'legitimate' claim for control of Egypt and they thus posed a potential threat to the rulers of Egypt."[51]: 66–67

Herodotus mentioned an invasion of Kush by the Achaemenid ruler Cambyses (c. 530 BC). By some accounts Cambyses succeeded in occupying the area between the first and second Nile cataract,[54] however Herodotus mentions that "his expedition failed miserably in the desert."[51]: 65–66 Achaemenid inscriptions from both Egypt and Iran include Kush as part of the Achaemenid empire.[55] For example, the DNa inscription of Darius I (r. 522–486 BC) on his tomb at Naqsh-e Rustam mentions Kūšīyā (Old Persian cuneiform: 𐎤𐎢𐏁𐎡𐎹𐎠, pronounced Kūshīyā) among the territories being "ruled over" by the Achaemenid Empire.[56][55] Derek Welsby states "scholars have doubted that this Persian expedition ever took place, but... archaeological evidence suggests that the fortress of Dorginarti near the second cataract served as Persia's southern boundary."[51]: 65–66

From around 425–300 BC, beginning under the rule of king Amannote-erike, Kush saw a series of kings who revitalized older practices such as the erection of royal steles or royal statues. It was likely also in this period when several older pyramids, among them that of Taharqo, were enlarged. The stele of king Harsiotef, who from around 400 BC ruled for at least 35 years, reports how he fought a multitude of campaigns against enemies ranging from Meroe in the south to Lower Nubia in the north while also donating to temples throughout Kush. King Nastasen (c. 325) waged several wars against nomad groups and again in Lower Nubia.[57] Nastasen was the last king to be buried at Nuri.[58] His successors built six pyramids at Jebel Barkal and two in the old necropolis of el-Kurru, although the lack of inscriptions prevents identifying their occupants. It seems likely that this was a time of unrest and conflict within the royal elite.[59]

Meroitic period (c. 270 BC–4th century AD)

Aspelta moved the capital to Meroë, considerably farther south than Napata, possibly c. 591 BC,[60] just after the sack of Napata by Psamtik II. Martin Meredith states the Kushite rulers chose Meroë, between the Fifth and Sixth Cataracts, because it was on the fringe of the summer rainfall belt, and the area was rich in iron ore and hardwood for iron working. The location also afforded access to trade routes to the Red Sea. The Kush traded iron products with the Romans, in addition to gold, ivory and slaves. The Butana plain was stripped of its forests, leaving behind slag piles.[61][62]

In about 300 BC, the move to Meroë was made more complete when the monarchs began to be buried there, instead of at Napata. One theory is that this represents the monarchs breaking away from the power of the priests at Napata. According to Diodorus Siculus, Kushite king Ergamenes defied the priests and had them slaughtered. This story may refer to the first ruler to be buried at Meroë with a similar name such as Arqamani,[63] who ruled many years after the royal cemetery was opened at Meroë. During this same period, the Kushite authority may have extended some 1,500 km along the Nile River valley from the Egyptian frontier in the north to areas far south of modern Khartoum and probably also substantial territories to the east and west.[64]

There is some record of conflict between the Kushites and Ptolemies. In 275 or 274 BC, Ptolemy II (r. 283–246 BC) sent an army to Nubia, and defeated the Kingdom of Kush, annexing to Egypt the area later known as Triakontaschoinos. In addition, There was a serious revolt at the end of Ptolemy IV, around 204 BC, and the Kushites likely tried to interfere in Ptolemaic affairs.[51]: 67 It has been suggested that this led to Ptolemy V defacing the name of Arqamani on inscriptions at Philae.[51]: 67 "Arqamani constructed a small entrance hall to the temple built by Ptolemy IV at selchis and constructed a temple at Philae to which Ptolemy contributed an entrance hall."[51]: 66 There is evidence of Ptolemaic occupation as far south as the second cataract, but recent finds at Qasr Ibrim, such as "the total absence of Ptolemaic pottery" have cast doubts on the effectiveness of the occupation. Dynastic struggles led to the Ptolemies abandoning the area, so "the Kushites reasserted their control...with Qasr Ibrim occupied" (by the Kushites) and other locations perhaps garrisoned.[51]: 67

According to Welsby, after the Romans assumed control of Egypt, they negotiated with the Kushites at Philae and drew the southern border of Roman Egypt at Aswan.[51]: 67 Theodor Mommsen and Welsby state the Kingdom of Kush became a client Kingdom, which was similar to the situation under Ptolemaic rule of Egypt. Kushite ambition and excessive Roman taxation are two theories for a revolt that was supported by Kushite armies.[51]: 67–68 The ancient historians, Strabo and Pliny, give accounts of the conflict with Roman Egypt.

Strabo describes a war with the Romans in the first century BC. According to Strabo, the Kushites "sacked Aswan with an army of 30,000 men and destroyed imperial statues...at Philae." A "fine over-life-size bronze head of the emperor Augustus" was found buried in Meroe in front of a temple.[51]: 68 After the initial victories of Kandake (or "Candace") Amanirenas against Roman Egypt, the Kushites were defeated and Napata sacked.[65] Remarkably, the destruction of the capital of Napata was not a crippling blow to the Kushites and did not frighten Candace enough to prevent her from again engaging in combat with the Roman military. In 22 BC, a large Kushite force moved northward with intention of attacking Qasr Ibrim.[66]: 149 Alerted to the advance, Gaius Petronius, prefect of Roman Egypt, again marched south and managed to reach Qasr Ibrim and bolster its defenses before the invading Kushites arrived. Welsby states after a Kushite attack on Primis (Qasr Ibrim),[51]: 69–70 the Kushites sent ambassadors to negotiate a peace settlement with Petronius. The Kushites succeeded in negotiating a peace treaty on favorable terms.[65] Trade between the two nations increased[66]: 149 and the Roman Egyptian border being extended to "Hiera Sykaminos (Maharraqa)."[51]: 70 This arrangement "guaranteed peace for most of the next 300 years" and there is "no definite evidence of further clashes."[51]: 70

It is possible that the Roman emperor Nero planned another attempt to conquer Kush before his death in AD 68.[66]: 150–151 Nero sent two centurions upriver as far as Bahr el Ghazal River in 66 AD in an attempt to discover the source of the Nile, per Seneca,[61]: 43 or plan an attack, per Pliny.

Decline and fall

Kush began to fade as a power by the first or second century AD, sapped by the war with the Roman province of Egypt and the decline of its traditional industries.[67] However, there is evidence of third century AD Kushite Kings at Philae in demotic and inscription.[51]: 71 It has been suggested that the Kushites reoccupied lower Nubia after Roman forces were withdrawn to Aswan. Kushite activities led others to note "a de facto Kushite control of that area (as far north as Philae) for part of the third century AD.[51]: 71 Thereafter, it weakened and disintegrated due to internal rebellion.[citation needed]

The fall of Meroe is often associated with an Aksumite invasion.[68] An Aksumite presence in Meroe is confirmed by two fragmentary Greek inscriptions.[69] The better preserved one referred to military actions and the imposition of a tribute.[70] They probably belonged to Aksumite victory monuments and were dedicated to Ares/Maher, the god of war.[71] Thus, they must have been erected before Aksum's conversion to Christianity in around 340, perhaps by king Ousanas (r. c. 310–330).[72] An inscription from Aksum mentioning Kush as vassal kingdom may also be attributed to Ousanas.[73] The trilingual stele of his successor Ezana describes another expedition which happened after 340.[74] Ezana's army followed the course of the Atbara until reaching the Nile confluence, where he waged war against Kush.[75] Meroe itself is not mentioned, suggesting that Ezana did not attack the town.[76] Aksum's presence in Nubia was likely short-lived.[77]

Meroitic texts from as early as the 1st century BC hint to conflicts with the Noba, who lived west of the Nile and were governed by their own chiefs and kings. Perhaps it was the increasingly arid climate that forced them to attack the Nile Valley, although they would not manage to break through until the 4th century.[78] The Ezana stele mentioned that they had occupied Kushite towns[79] and were active as far east as the Takeze River, where they harassed Aksumite vassals.[80] These attacks and them breaking oaths they had sworn to Ezana were the main reason for his Nubian expedition.[81] It has been proposed that the Noba were not necessarily Nubian-speakers, but that the term "Noba" was rather a pejorative Meroitic word applied to a large variety of people living outside the Meroitic state.[82] A Meroitic stele found at Gebel Adda from around 300 AD, however, seems to mention a king bearing the Nubian name Trotihi.[83] A bowl from a 4th-century elite burial in el-Hobagi features a Meroitic-Nubian inscription mentioning a "king", but identifying the interred individual and the polity he ruled over remains problematic.[83][84]

At Meroe, the last pyramids as well as non-royal burials are dated to the mid-4th century,[85] which is conventionally thought to be when the kingdom of Kush came to an end. Afterwards began the so-called "post-Meroitic" period.[86] This period saw a decline of urbanism, the disappearance of the Meroitic religion and script[87] as well as the emergence of regional elites buried in large tumuli.[88] Princely burials from Qustul (c. 380–410) and Ballana (410–500) in Lower Nubia are connected to the rise of Nobatia.[89] To its north were the Blemmyes, who in around 394 established a kingdom centered around Talmis[90] that lasted until it was conquered by Nobatia in around 450.[91] The political developments south of the third cataract remain obscure,[92] but it appears that Dongola, the later capital of Makuria as well as Soba, the capital of Alodia, were founded in that period. Nobatia, Makuria and Alodia eventually converted to Christianity in the 6th century, marking the beginning of medieval Nubia.[93]

Language and writing

The Meroitic language was spoken in Meroë and Sudan during the Meroitic period (attested from 300 BC). It became extinct around 400 AD. It is uncertain to which language family the Meroitic language belongs. Kirsty Rowan suggests that Meroitic, like the Egyptian language, belongs to the Afro-Asiatic family. She bases this on its sound inventory and phonotactics, which she argues are similar to those of the Afro-Asiatic languages and dissimilar from those of the Nilo-Saharan languages.[94][95] Claude Rilly proposes that Meroitic, like the Nobiin language, belongs to the Eastern Sudanic branch of the Nilo-Saharan family, based in part on its syntax, morphology, and known vocabulary.[96][97][98]

In the Napatan Period Egyptian hieroglyphs were used: at this time writing seems to have been restricted to the court and temples. From the second century BC, there was a separate Meroitic writing system. The language was written in two forms of the Meroitic alphabet: Meroitic Cursive, which was written with a stylus and was used for general record-keeping; and Meroitic Hieroglyphic, which was carved in stone or used for royal or religious documents. It is not well understood due to the scarcity of bilingual texts. The earliest inscription in Meroitic writing dates from between 180 and 170 BC. These hieroglyphics were found engraved on the temple of Queen Shanakdakhete. Meroitic Cursive is written horizontally, and reads from right to left.[99] This was an alphabetic script with 23 signs used in a hieroglyphic form (mainly on monumental art) and in a cursive form. The latter was widely used; so far some 1,278 texts using this version are known (Leclant 2000). The script was deciphered by Griffith, but the language behind it is still a problem, with only a few words understood by modern scholars. It is not as yet possible to connect the Meroitic language with other known languages.[49] For a time, it was also possibly used to write the Old Nubian language of the successor Nubian kingdoms.[100]

Technology, medicine, and mathematics

Technology

The natives of the Kingdom of Kush developed a type of water wheel or scoop wheel, the saqiyah, named kolē by the Kush.[101] The saqiyah was developed during the Meroitic period to improve irrigation. The introduction of this machine had a decisive influence on agriculture especially in Dongola as this wheel lifted water 3 to 8 meters with much less expenditure of labor and time than the shaduf, which was the previous chief irrigation device in the kingdom. The shaduf relied on human energy but the saqiyah was driven by buffalos or other animals.[101] The people of Kerma, ancestors to the Kushites, built bronze kilns through which they manufactured objects of daily use such as razors, mirrors and tweezers.[102]

The Kushites developed a form of reservoir, known as a hafir, during the Meroitic period. Eight hundred ancient and modern hafirs have been registered in the Meroitic town of Butana.[103] The functions of hafirs were to catch water during the rainy season for storage, to ensure water is available for several months during the dry season as well as supply drinking water, irrigate fields, and water cattle.[103] The Great Hafir, or Great Reservoir, near the Lion Temple in Musawwarat es-Sufra is a notable hafir built by the Kushites.[104] It was built to retain the rainfall of the short, wet season. It is 250 m in diameter and 6.3 m deep.[104][103]

Bloomeries and blast furnaces could have been used in metalworking at Meroë.[105] Early records of bloomery furnaces dated at least to seventh and sixth century BC have been discovered in Kush. The ancient bloomeries that produced metal tools for the Kushites produced a surplus for sale.[106][107][108]

Medicine

Nubian mummies studied in the 1990s revealed that Kush was a pioneer of early antibiotics.[109]

Tetracycline was being used by Nubians, based on bone remains between 350 AD and 550 AD. The antibiotic was in wide commercial use only in the mid 20th century. The theory states that earthen jars containing grain used for making beer contained the bacterium streptomyces, which produced tetracycline. Although Nubians were not aware of tetracycline, they could have noticed that people fared better by drinking beer. According to Charlie Bamforth, a professor of biochemistry and brewing science at the University of California, Davis, "They must have consumed it because it was rather tastier than the grain from which it was derived. They would have noticed people fared better by consuming this product than they were just consuming the grain itself."[110]

Mathematics

Based on engraved plans of Meroitic King Amanikhabali's pyramids, Nubians had a sophisticated understanding of mathematics as they appreciated the harmonic ratio. The engraved plans is indicative of much to be revealed about Nubian mathematics.[111] The ancient Nubians also established a system of geometry which they used in creating early versions of sun clocks.[112][113] During the Meroitic period in Nubian history, the Nubians used a trigonometric methodology similar to the Egyptians.[114]

Military

During the siege of Hermopolis in the eighth century BC, siege towers were built for the Kushite army led by Piye, in order to enhance the efficiency of Kushite archers and slingers.[115] After leaving Thebes, Piye's first objective was besieging Ashmunein. Following his army's lack of success he undertook the personal supervision of operations including the erection of a siege tower from which Kushite archers could fire down into the city.[116] Early shelters protecting sappers armed with poles trying to breach mud-brick ramparts gave way to battering rams.[115]

Bowmen were the most important force components in the Kushite military.[117] Ancient sources[which?][who?] indicate that Kushite archers favored one-piece bows that were between six and seven feet long, with a draw strength so powerful that many of the archers used their feet to bend their bows. However, composite bows were also used in their arsenal.[117] Greek historian Herodotus indicated that primary bow construction was of seasoned palm wood, with arrows made of cane.[117] Kushite arrows were often poisoned-tipped.

Elephants were occasionally used in warfare during the Meroitic period, as seen in the war against Rome around 20 BC.[118]

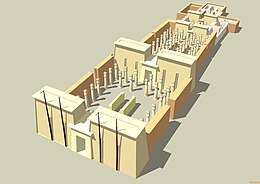

Architecture

During the Bronze Age, Nubian ancestors of the Kingdom of Kush built speoi (a speos is a temple or tomb cut into a rock face) between 3700 and 3250 BC. This greatly influenced the architecture of the New Kingdom of Egypt.[120] Tomb monuments were one of the more recognizable expressions of Kushite architecture. Uniquely Kushite tomb monuments were found from the beginning of the empire, at el Kurru, to the decline of the kingdom. These monuments developed organically from Middle Nile (e.g. A-group) burial types. Tombs became progressively larger during the 25th dynasty, culminating in Taharqa's underground rectangular building with "aisles of square piers...the whole being cut from the living rock."[51]: 103 Kushites also created pyramids,[121][122] mud-brick temples (deffufa), and masonry temples.[123][124] Kushites borrowed much from Egypt, as it relates to temple design. Kushite temples were quite diverse in their plans, except for the Amun temples which all have the same basic plan. The Jebel Barkal and Meroe Amun temples are exceptions with the 150 m long Jebel Barkal being "by far the largest 'Egyptian' temple ever built in Nubia."[51]: 118 Temples for major Egyptian deities were built on "a system of internal harmonic proportions" based on "one or more rectangles each with sides in the ratio of 8:5"[51]: 133 [125] Kush also invented Nubian vaults.

Piye is thought to have constructed the first true pyramid at el Kurru. Pyramids are "the archetypal tomb monument of the Kushite royal family" and found at "el Kurru, Nuri, Jebel Barkal, and Meroe."[51]: 105 The Kushite pyramids are smaller with steeper sides than northern Egyptian pyramids. The Kushites are thought to have copied the pyramids of New Kingdom elites, as opposed to Old and Middle Kingdom pharaohs.[51]: 105–106 Kushite housing consisted mostly of circular timber huts with some apartment houses with several two-room apartments. The apartment houses likely accommodated extended families.[citation needed]

The Kushites built a stone-paved road at Jebel Barkal, are thought to have built piers/harbors on the Nile river, and many wells.[126]

Economy

Some scholars[who?] believe the economy in the Kingdom of Kush was a redistributive system. The state would collect taxes in the form of surplus produce and would redistribute it to the people. Others believe that most of the society worked on the land and required nothing from the state and did not contribute to the state. Northern Kush seems to have been more productive and wealthier than the Southern area.[127]

Kush and Egyptology

On account of the Kingdom of Kush's proximity to Ancient Egypt – the first cataract at Elephantine usually being considered the traditional border between the two polities – and because the 25th dynasty ruled over both states in the eighth century BC, from the Rift Valley to the Taurus mountains, historians have closely associated the study of Kush with Egyptology, in keeping with the general assumption that the complex sociopolitical development of Egypt's neighbors can be understood in terms of Egyptian models.[citation needed] As a result, the political structure and organization of Kush as an independent ancient state has not received as thorough attention from scholars, and there remains much ambiguity especially surrounding the earliest periods of the state.[citation needed] Edwards has suggested that the study of the region could benefit from increased recognition of Kush as a state in its own right, with distinct cultural conditions, rather than merely as a secondary state on the periphery of Egypt.[128]

Gallery

- Portrait of Taharqa, Kerma Museum

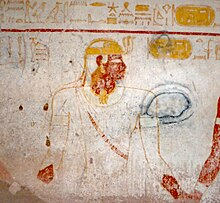

- The "Archer King", an unknown king of Meroe, 3rd century BC. National Museum of Sudan.

- Taharqa's shrine, Ashmolean museum in Oxford, UK

- Taharqa's kiosk, Karnak Temple

- Pharaoh Taharqa of Ancient Egypt's 25th Dynasty. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford UK

- Meroitic pottery, Nelluah (Egyptian Nubia)

See also

- Aethiopia is an ancient Greek geographical term which referred to the regions of Sudan and areas south of the Sahara desert.

- List of monarchs of Kush

- Merowe Dam

- Nubiology

- Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt family tree

References

- ^ Török 1997, p. 2 (1997 ed.).

- ^ Kuckertz, Josefine (2021). "Meroe and Egypt". UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology: 22.

- ^ "Dive beneath the pyramids of Sudan's black pharaohs". National Geographic. 2 July 2019. Archived from the original on July 2, 2019.

- ^ Török 1997, p. 49 (1997 ed.).

- ^ Rilly, Claude (2019). "Languages of Ancient Nubia". In Raue, Dietrich (ed.). Handbook of Ancient Nubia. De Gruyter. pp. 133–4. ISBN 978-3-11-041669-5. Retrieved 2019-11-20.

The Blemmyan language is so close to modern Beja that it is probably nothing else than an early dialect of the same language.

- ^ "Kushite Religion". encyclopedia.com.

- ^ a b Stearns, Peter N., ed. (2001). "(II.B.4.) East Africa, c. 2000–332 B.C.E.". The Encyclopedia of World History: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern, Chronologically Arranged (6th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-395-65237-4.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "The Kingdoms of Kush". National Geographic Society. 2018-07-20. Archived from the original on 2020-05-05. Retrieved 2020-08-29.

- ^ Alberge, Dalya. "Tomb reveals Ancient Egypt's humiliating secret". The Times. London.

- ^ Török 1997, pp. 144–6.

- ^ Derek Welsby (2014): "The Kingdom of Alwa" in "The Fourth Cataract and Beyond". Peeters.

- ^ Isma'il Kushkush; Matt Stirn. "Why Sudan's Remarkable Ancient Civilization Has Been Overlooked by History". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2020-08-23.

- ^ Goldenberg, David M. (2005). The Curse of Ham: Race and Slavery in Early Judaism, Christianity, and Islam (New ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-691-12370-7.

- ^ Spalinger, Anthony (1974). "Esarhaddon and Egypt: An Analysis of the First Invasion of Egypt". Orientalia. Nova Series. 43: 295–326, XI.

- ^ Allen, James P. (2013-07-11). The Ancient Egyptian Language: An Historical Study. Cambridge University Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-107-03246-0. Retrieved 2015-04-15.

- ^ a b c Török 1997.

- ^ Van, de M. M. A History of Ancient Egypt. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011. Print.

- ^ "GENESIS 10:10 KJV "And the beginning of his kingdom was Babel, and Erech, and Accad, and Calneh, in the land of Shinar."". www.kingjamesbibleonline.org.

- ^ "PSALMS CHAPTER 7 KJV". www.kingjamesbibleonline.org.

- ^ Török 1997, p. 69 ff (1997 ed.).

- ^ Hafsaas-Tsakos, Henriette (2009). "The Kingdom of Kush: An African Centre on the Periphery of the Bronze Age World System". Norwegian Archaeological Review. 42 (1): 50–70. doi:10.1080/00293650902978590. S2CID 154430884.

- ^ Historical Dictionary of Ancient and Medieval Nubia, Richard A. Lobban Jr., p. 254.

- ^ De Mola, Paul J. "Interrelations of Kerma and Pharaonic Egypt". Ancient History Encyclopedia: https://www.worldhistory.org/article/487/

- ^ "Jebal Barkal: History and Archaeology of Ancient Napata". Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 21 March 2012.

- ^ Wilkinson, Toby (2016). Writings from Ancient Egypt. United Kingdom: Penguin Classics. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-14-139595-1.

- ^ Flavius Josephus. 'Antiquities of the Jews'. Whiston 2-10-2.

- ^ Williams 2020, pp. 413–414.

- ^ Morkot, Robert G. "On the Priestly Origin of the Napatan Kings: The Adaptation, Demise, and Resurrection of Ideas in Writing Nubian History" in O'Connor, David and Andrew Reid, eds. Ancient Egypt in Africa (Encounters with Ancient Egypt) (University College London Institute of Archaeology Publications) Left Coast Press (1 Aug 2003) ISBN 978-1-59874-205-3 p.151

- ^ a b c Emberling 2023, p. 110.

- ^ Török 1997, p. 123.

- ^ Török 1997, pp. 123–125.

- ^ Kendall 1999, p. 45.

- ^ Török 1997, p. 126.

- ^ Shaw (2002) p. 345

- ^ a b c d Edwards, David (2004). The Nubian Past. Oxon: Routledge. pp. 2, 75, 77–78. ISBN 978-0-415-36988-6.

- ^ Ducommun, Janine A.; Elshazly, Hesham (April 15, 2009). "Kerma and the royal cache" – via Academia.edu.

- ^ a b Kendall, T.K., 2002. Napatan Temples: a Case Study from Gebel Barkal. The Mythological Nubian Origin of Egyptian Kingship and the Formation of the Napatan State. Tenth International Conference of Nubian Studies. Rome, September 9–14, 2002.

- ^ Török 1997, pp. 132–3, 153–84.

- ^ Aubin, Henry T. (2002). The Rescue of Jerusalem. New York, NY: Soho Press, Inc. pp. x, 141–144. ISBN 1-56947-275-0.

- ^ Aubin, Henry T. (2002). The Rescue of Jerusalem. New York, NY: Soho Press, Inc. pp. x, 127, 129–130, 139–152. ISBN 1-56947-275-0.

- ^ Aubin, Henry T. (2002). The Rescue of Jerusalem. New York, NY: Soho Press, Inc. pp. x, 119. ISBN 1-56947-275-0.

- ^ Török 1997, p. 170.

- ^ Diop, Cheikh Anta (1974). The African Origin of Civilization. Chicago, Illinois: Lawrence Hill Books. pp. 219–221. ISBN 1-55652-072-7.

- ^ Bonnet, Charles (2006). The Nubian Pharaohs. New York: The American University in Cairo Press. pp. 142–154. ISBN 978-977-416-010-3.

- ^ Digital Collections, The New York Public Library. "(still image) Aethiopen. Barkal [Jebel Barkal]. Nördliche Pyramidengruppe. Pyr. 15: a. Nordwand; b. Westwand., (1849–1856)". The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ Mokhtar, G. (1990). General History of Africa. California, USA: University of California Press. pp. 161–163. ISBN 0-520-06697-9.

- ^ Emberling, Geoff (2011). Nubia: Ancient Kingdoms of Africa. New York: Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. pp. 9–11.

- ^ Silverman, David (1997). Ancient Egypt. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 36–37. ISBN 0-19-521270-3.

- ^ a b "Meroitic script". www.digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk.

- ^ a b c d Török 1997, p. 185

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Welsby 1996, pp. 64–65

- ^ Georges Roux – Ancient Iraq pp. 330–332

- ^ Digital Collections, The New York Public Library. "(still image) Aethiopen. Dynastie XXV, 3. Barkal [Jebel Barkal]. Grosser Felsentempel, Ostwand der Vorhalle., (1849–1856)". The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ Dandamaev, M. A. (1989). A Political History of the Achaemenid Empire. BRILL. pp. 80–81. ISBN 9004091726.

- ^ a b Sircar, Dineschandra (1971). Studies in the Geography of Ancient and Medieval India. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 25. ISBN 9788120806900.

- ^ Line 30 of the DNa inscription

- ^ Emberling 2023, pp. 140–141.

- ^ Török 1997, p. 394.

- ^ Emberling 2023, pp. 141–143.

- ^ Festus Ugboaja Ohaegbulam (1 October 1990). Towards an understanding of the African experience from historical and contemporary perspectives. University Press of America. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-8191-7941-8. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ a b Meredith, Martin (2014). The Fortunes of Africa. New York: Public Affairs. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-1-61039-635-6.

- ^ Shillington, Kevin (2012). History of Africa. London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-0-230-30847-3.

- ^ Fage, J. D.: Roland Anthony Oliver (1979) The Cambridge History of Africa, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-21592-7 p. 228 [1]

- ^ Edwards, page 141

- ^ a b Arthur E. Robinson, "The Arab Dynasty of Dar For (Darfur): Part II", Journal of the Royal African Society (Lond). XXVIII: 55–67 (October, 1928)

- ^ a b c Jackson, Robert B. (2002). At Empire's Edge: Exploring Rome's Egyptian Frontier. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-08856-6.

- ^ "BBC World Service – The Story of Africa". www.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ Hatke 2013, p. 67.

- ^ Hatke 2013, pp. 71–75.

- ^ Hatke 2013, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Hatke 2013, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Hatke 2013, pp. 67, 76–77, 94.

- ^ Hatke 2013, pp. 69–71.

- ^ Hatke 2013, p. 94.

- ^ Hatke 2013, p. 116.

- ^ Hatke 2013, p. 145.

- ^ Hatke 2013, p. 79.

- ^ Rilly 2008, pp. 215–217.

- ^ Hatke 2013, p. 114.

- ^ Hatke 2013, p. 104.

- ^ Hatke 2013, p. 121.

- ^ Edwards 2011, pp. 503–508.

- ^ a b Rilly 2019, p. 138.

- ^ Sakamoto 2022, pp. 369–370.

- ^ Török 2009, p. 517.

- ^ el-Tayeb 2020, pp. 772–773.

- ^ Edwards 2019, p. 947.

- ^ Edwards 2019, p. 950.

- ^ Török 2009, pp. 520–521.

- ^ Török 2009, pp. 524–525.

- ^ Török 2009, pp. 527–528.

- ^ Török 2009, pp. 537–538.

- ^ Edwards 2013, p. 791.

- ^ Rowan, Kirsty (2011). "Meroitic Consonant and Vowel Patterning". Lingua Aegytia, 19.

- ^ Rowan, Kirsty (2006), "Meroitic – An Afroasiatic Language?" Archived 2015-12-27 at the Wayback Machine SOAS Working Papers in Linguistics 14:169–206.

- ^ Rilly, Claude; de Voogt, Alex (2012). The Meroitic Language and Writing System. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-00866-3.

- ^ Rilly, Claude (2004). "The Linguistic Position of Meroitic" (PDF). Sudan Electronic Journal of Archaeology and Anthropology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2017-11-02.

- ^ Rilly, Claude (2016). "Meroitic". In Stauder-Porchet, Julie; Stauder, Andréas; Willeke, Wendrich (eds.). UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology. Los Angeles: UCLA.

- ^ Fischer, Steven Roger (2004). History of Writing. Reaktion Books. pp. 133–134. ISBN 1-86189-588-7. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ^ ""Meroe: Writing", Digital Egypt, University College, London". Digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk. Retrieved 2012-09-06.

- ^ a b Ki-Zerbo, J.; Mokhtar, G. (1981). Ancient civilizations of Africa. Unesco. International Scientific Committee for the Drafting of a General History of Africa. p. 309. ISBN 978-0-435-94805-4. Retrieved 2012-06-19.

- ^ Bianchi 2004, p. 81.

- ^ a b c Hintze 1963, pp. 222–4

- ^ a b Näser, Claudia (2010), "The Great Hafir at Musawwarat es-Sufra: Fieldwork of the Archaeological Mission of Humboldt University Berlin in 2005 and 2006", in Godlewski, Włodzimierz; Łajtar, Adam (eds.), Between the Cataracts. Proceedings of the 11th Conference of Nubian Studies, Warsaw University, 27 August – 2 September 2006, Part two, fascicule 1: Session papers, PAM Suppl. Series 2.2/1, Warsaw: Warsaw University Press, pp. 39–46, doi:10.31338/uw.9788323533344, ISBN 978-83-235-3334-4, retrieved 2020-10-04

- ^ Humphris et al. 2018, p. 399.

- ^ Collins, Robert O.; Burns, James M. (8 February 2007). A History of Sub-Saharan Africa. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86746-7.

- ^ Edwards, David N. (29 July 2004). The Nubian Past: An Archaeology of the Sudan. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-203-48276-6.

- ^ Humphris et al. 2018, pp. 399–416.

- ^ Armelagos, George (2000). "Take Two Beers and Call Me in 1,600 Years: Use of Tetracycline by Nubians and Ancient Egyptians". Natural History. 109: 50–3. S2CID 89542474.

- ^ Roach, John (17 May 2005). "Antibiotic Beer Gave Ancient Africans Health Buzz". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 7 February 2021. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- ^ Bianchi 2004, p. 230.

- ^ Depuydt, Leo (1 January 1998). "Gnomons at Meroë and Early Trigonometry". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 84: 171–180. doi:10.2307/3822211. JSTOR 3822211.

- ^ Slayman, Andrew (27 May 1998). "Neolithic Skywatchers". Archaeology Magazine Archive. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ Neugebauer, O. (2004-09-17). A History of Ancient Mathematical Astronomy. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-540-06995-9.

- ^ a b "Siege warfare in ancient Egypt". Tour Egypt. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ Dodson, Aidan (1996). Monarchs of the nile. American Univ. in Cairo Press. p. 178. ISBN 978-9774246005.

- ^ a b c Jim Hamm. 2000. The Traditional Bowyer's Bible, Volume 3, pp. 138-152

- ^ Nicolle, David (26 March 1991). Rome's enemies. Illustrated by Angus McBride. London: Osprey. pp. 11–15. ISBN 1-85532-166-1. OCLC 26551074.

- ^ "Gebel Barkal and the Sites of the Napatan Region". UNESCO – World Heritage Convention.

- ^ Bianchi 2004, p. 227.

- ^ Digital Collections, The New York Public Library. "(still image) Aethiopen. Begerauîeh [Begrawiya]. Pyramidengruppe A. Pyr. 9. Südwand., (1849–1856)". The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ Digital Collections, The New York Public Library. "(still image) Aethiopen. Begerauîeh [Begrawiya]. Pyramidengruppe A. Pyr. 15. Pylon., (1849–1856)". The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ Digital Collections, The New York Public Library. "(still image) Aethiopen. Naga [Naqa]. Tempel a. Vorderseite des Pylons., (1849–1856)". The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ Digital Collections, The New York Public Library. "(still image) Aethiopen. Begerauîeh [Begrawiya]. Pyramidengruppe A. Pyr. 31. Pylon., (1849–1856)". The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ Digital Collections, The New York Public Library. "(still image) Aethiopen. Begerauîeh [Begrawiya]. Pyramidengruppe A. Pyr. 14. Westwand., (1849–1856)". The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ John Noble Wilford, "Scholars Race to Recover a Lost Kingdom on the Nile", New York Times (June 19, 2007)

- ^ Welsby 1996, p. [page needed]

- ^ "David N. Edwards, "Meroe and the Sudanic Kingdoms", "Journal of African History" (UK). Vol. 39 No. 2 (1998), pp 175–193".

Sources

- Bianchi, Robert Steven (2004). Daily Life of the Nubians. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-32501-4.

- Emberling, Geoff (2023). "Kush under the Dynasty of Napata". In Karen Radner; Nadine Moeller; D.T. Potts (eds.). The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East. Vol. 4. Oxford University. pp. 82–160.

- Edwards, David N. (2004). The Nubian Past. London: Routledge. pp. 348 Pages. ISBN 0-415-36987-8.

- Edwards (2011). "From Meroe to 'Nubia' – exploring culture change without the 'Noba'". La Pioche et La Plume (Hommages Archéologiques à Patrice Lenoble). pp. 501–514.

- Edwards, David (2013). "Medieval and post-medieval states of the Nile Valley". In Peter Mitchell, Paul Lane (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of African Archaeology. Oxford University. pp. 789–798.

- Edwards, David (2019). "Post-Meroitic Nubia". In Dietrich Raue (ed.). Handbook of Ancient Nubia. De Gruyter. pp. 943–964.

- el-Tayeb, Mahmoud (2020). "Post-Meroe in Upper Nubia". The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia. Oxford University. pp. 731–758.

- Fisher, Marjorie M.; Lacovara, Peter; Ikram, Salima; et al., eds. (2012). Ancient Nubia: African Kingdoms on the Nile. The American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-416-478-1.

- Hatke, George (2013). Aksum and Nubia. Warfare, Commerce, and Political Fictions in Ancient Northeast Africa. New York University.

- Hintze, Fritz (1963). "Musawwarat as Sufra. Preliminary Report on the Excavations of the Institute of Egyptology, Humboldt University, Berlin, 1961–62" (PDF). Kush: Journal of the Sudan Antiquities Service. Vol. XI. The Service.

- Humphris, Jane; et al. (June 2018). "Iron Smelting in Sudan: Experimental Archaeology at The Royal City of Meroe". Journal of Field Archaeology. 43 (5): 399–416. doi:10.1080/00934690.2018.1479085.

- Kendall, T. (1999). "The Origin of the Napatan State: El Kurru and the Evidence of the Royal Ancestors". In Steffen Wenig (ed.). Studien Zum Antiken Sudan Akten Der 7. Internationalen Tagung Für Meroitische Forschungen Vom 14. Bis 19. September 1992 in Gosen/bei Berlin. Harrassowitz. pp. 3–117.

- Leclant, Jean (2004). The empire of Kush: Napata and Meroe. London: UNESCO. pp. 1912 Pages. ISBN 1-57958-245-1.

- Rilly, Claude (2008). "Enemy brothers: Kinship and relationship between Meroites and Nubians (Noba)". Between the Cataracts: Proceedings of the 11th Conference of Nubian Studies, Warsaw, 27 August – 2 September 2006. Part One. PAM. pp. 211–225. ISBN 978-83-235-0271-5.

- Rilly, Claude. "Languages of Ancient Nubia". In Dietrich Raue (ed.). Handbook of Ancient Nubia. De Gruyter. pp. 129–154.

- Sakamoto, Tsubasa (2022). "A (Post-)Meroitic chieftain at Jebel Umm Marrihi". In N. Kawai, B.G. Davies (ed.). The Star Who Appears in Thebes. Studies in Honour of Jiro Kondo. Abercromby. pp. 369–382.

- Oliver, Roland (1975). The Cambridge History of Africa Volume 3 1050 – c. 1600. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-20981-1.

- Oliver, Roland (1978). The Cambridge history of Africa. Vol. 2, From c. 500 BC to AD 1050. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-20981-1.

- Shillington, Kevin (2004). Encyclopedia of African History, Vol. 1. London: Routledge. pp. 1912 Pages. ISBN 1-57958-245-1.

- Török, László (1997). "The Kingdom of Kush: Handbook of the Napatan-Meroitic Civilization". Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 1 the Near and Middle East. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-9004104488.

- Török, László (2009). Between Two Worlds. The Frontier Region between Ancient Nubia and Egypt 3700 BC – AD 500. Brill.

- Welsby, Derek (1996). The Kingdom of Kush: the Napatan and Meroitic empires. London: Published for the Trustees of the British Museum by British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-0986-2. OCLC 34888835.

- Williams, Bruce Beyer (2020). "The Napatan Neo-Kushite State 1: The Intermediate Period and Second Empire". In Bruce Beyer Williams (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia. Oxford University. pp. 411–422.

Further reading

- Baud, Michel (2010). Méroé. Un empire sur le Nil (in French). Officina Libraria. ISBN 978-8889854501.

- Breyer, Francis (2014). Einführung in die Meroitistik (in German). Lit. ISBN 978-3-643-12805-8.

- Lenoble, Patrice (2018). El-Hobagi: Une Necropole De Rang Imperial Au Soudan Central. Institut Francais D'archeologie Orientale.

- Pope, Jeremy (2014). The Double Kingdom Under Taharqa. Brill.

- Valbelle, Dominique; Bonnet, Charles (2006). The Nubian Pharaohs. The American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-9774160103.

- Yvanes, Elsa (2018). "Clothing the elite? Patterns of textile production and consumption in ancient Sudan and Nubia". Dynamics and Organisation of Textile Production in Past Societies in Europe and the Mediterranean. Vol. 31. pp. 81–92.

External links

- Dan Morrison, "Ancient Gold Center Discovered on the Nile", National Geographic News

- "Civilizations in Africa: Kush", Washington State University Archived 2007-05-01 at the Wayback Machine

- "Remembering the Remarkable Queens Who Ruled Ancient Nubia" at Atlas Obscura, December 15, 2021

- African Kingdoms | Kush

- Ancient Sudan (Nubia) website[usurped]

- Joseph Poplicha, "The Biblical Nimrod and the Kingdom of Eanna", Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 49, (1929), pp. 303–317

- Kerma website Official website of the Swiss archeological mission to Sudan.

- Josefine Kuckertz: Meroe and Egypt. In Wolfram Grajetzki, Solange Ashby, Willeke Wendrich (eds.): UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology. Los Angeles 2021, ISSN 2693-7425 (online).