Mercury-Atlas 4

The launch of Mercury-Atlas 4 | |

| Names | Mercury-Atlas 4 MA-4 |

|---|---|

| Mission type | Test flight |

| Operator | NASA |

| Harvard designation | 1961 Alpha Alpha 1 |

| COSPAR ID | 1961-025A |

| SATCAT no. | 183 |

| Mission duration | 1 hour, 49 minutes, 20 seconds |

| Distance travelled | 41,919 kilometers (26,047 mi) |

| Orbits completed | 1 |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft | Mercury #8A |

| Manufacturer | McDonnell Aircraft |

| Launch mass | 1,224.7 kilograms (2,700 lb) |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | September 13, 1961, 14:04:16 UTC[1]: 2 |

| Rocket | Atlas LV-3B 88-D |

| Launch site | Cape Canaveral LC-14 |

| End of mission | |

| Recovered by | USS Decatur |

| Landing date | September 13, 1961, 15:53:36 UTC |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Regime | Low Earth |

| Perigee altitude | 85.93 nautical miles (159.14 km; 98.89 mi)[1]: 2 |

| Apogee altitude | 120.02 nautical miles (222.28 km; 138.12 mi)[1]: 2 |

| Inclination | 32.5 degrees |

| Period | 88.38 minutes |

| Epoch | September 13, 1961[2] |

Project Mercury Mercury-Atlas series | |

Mercury-Atlas 4 (MA-4) was an uncrewed test flight within NASA's Project Mercury program, launched on September 13, 1961, at 14:04:16 UTC[1] from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station Launch Complex 14. The mission's primary purpose was to evaluate the Mercury spacecraft's performance in orbit and to test the Mercury Space Flight Network. Despite initial technical challenges, Mercury-Atlas 4 successfully met its goals. The mission involved testing the Mercury spacecraft, specifically Mercury #8A, which completed one orbit around Earth. This successful flight provided important data and insights for NASA's Project Mercury, supporting the planning and development of upcoming crewed missions in the program.

Mission overview

Launch preparations

There were a series of delays getting the Atlas rocket and Mercury spacecraft ready as the postflight findings from Mercury-Atlas 3 had necessitated extensive modifications to the booster. Atlas vehicle 88D did not undergo its factory rollout inspection until June 30 and delivery to Cape Canaveral waited until July 15. Moreover, the flight was not going to use Mercury capsule #9 as planned, but instead capsule #8A, which had been recovered from the Mercury-Atlas 3 launch and refurbished. Capsule #8A was also the last of the older models with small port windows, no landing bag, and a heavy locking mechanism on the hatch.[3]

A series of delays occurred due to problems with the Atlas autopilot, including the replacement of a defective yaw rate gyro. Launch was originally intended for August 22 but pushed back. Further delays happened when it was discovered that the brand of transistor used in both the Atlas and Mercury were prone to forming solder balls, thus the entire last week of August was spent laboriously repairing them.[3]

Mission profile

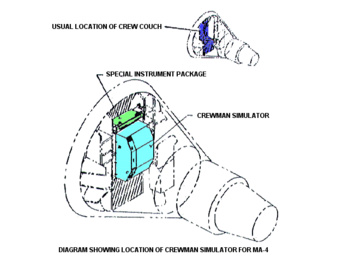

This flight was an orbital test of the Mercury Space Flight Network and the first successful orbital flight test of Project Mercury; all previous successful launches were suborbital. The payload consisted of a pilot simulator (to test the environmental controls), two voice tapes (to check the tracking network), a life support system, three cameras, and instrumentation to monitor levels of noise, vibration and radiation. Because it was suspected that a transient voltage caused the malfunction of Mercury-Atlas 3's programmer (and that a similar problem had been responsible for Big Joe's failure to stage),[3] Convair equipped the autopilot to give the engines a counteracting capability. Thus, testing this was also an objective of the flight. Also, the Atlas vehicle used to launch MIDAS 3 in July had experienced a programmer reset at staging, which did not have any significant effect or prevent the satellite from reaching orbit, but this incident was thoroughly investigated because of the problems with Mercury-Atlas 3; one modification to Mercury vehicles would involve removing the programmer's ability to reset itself in flight.[citation needed]

Of continuing concern were rough combustion and gyroscope malfunctions as these failure modes had destroyed two Atlas E vehicles in June. The Spin Motor Rotation Detection System, invented to prevent an Atlas from launching with an improperly operating gyroscope, was just being phased in and would not appear in a Mercury vehicle until Mercury-Atlas 5.

Mission highlights

The launch went well and the thick-skinned Atlas survived Max Q acceleration.[4] Capsule performance was also good despite some concern over high oxygen usage in orbit, but ground controllers did not consider it a serious problem and the oxygen supply was sufficient for at least 8 orbits. The process of turning the capsule around in orbit so its heat shield faced forward proved more difficult than expected, taking 50 seconds instead of the normal 20 seconds. At a few points during the mission, the capsule's attitude became slightly unstable due to the failure of two thrusters, which caused momentary telemetry dropouts. The capsule completed one orbit prior to returning to Earth. Reentry took place one hour and 28 minutes after launch, and splashdown occurred in the Atlantic Ocean 176 miles (283 kilometers) east of Bermuda.[4] One hour and 22 minutes after splashdown the destroyer USS Decatur[5] (which was 34 miles from the landing point)[4] picked up the capsule, which was found to be in good condition with little damage from either liftoff, orbit, or reentry.[6] Postflight examination found that the oxygen rate handle had been dislodged by liftoff-induced vibration and cracked open a valve. This had allowed oxygen to escape into space, but not at sufficient rates to trigger a telemetry warning measurement, although it did trigger the oxygen warning light in the capsule. The handle was redesigned afterwards to be more difficult to move. The problem reorienting the capsule after booster separation was found to be the result of an open circuit in the pitch gyro.

The biggest problem encountered on Mercury-Atlas 4 was an uncomfortably high level of liftoff vibration from T+5 to T+20 seconds, so a few more small modifications were made to the Atlas's autopilot. However, Manned Spaceflight Center director Bob Gilruth expressed his confidence that the booster was now man-rated, and that a human passenger would have survived the flight.

The MA-4 mission had successfully achieved all its flight objectives.[7] It had demonstrated the ability of the Atlas LV-3B rocket to lift the Mercury capsule into orbit and of the capsule and its systems to operate completely autonomously, and it had succeeded in obtaining pictures of the Earth. Nonetheless, to be on the safe side and test out a few more design changes, NASA still planned for one more uncrewed test before committing the Mercury-Atlas combo to a crewed flight.[4]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d Morrison, A.; Chown, M. C. (December 1964). Photography of the Western Sahara desert from the Mercury MA-4 spacecraft (PDF) (Technical report). McGill University and NASA. CR-124. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 13, 2023. Retrieved November 13, 2023.

- ^ McDowell, Jonathan. "SATCAT". Jonathan's Space Pages. Retrieved March 23, 2014.

- ^ a b c Swenson Jr., Loyd S.; Grimwood, James M.; Alexander, Charles C. (1989). "This New Ocean - Chapter 12 - Final Rehearsals". NASA. SP-4201. Archived from the original on September 24, 2022. Retrieved November 14, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Swenson Jr., Loyd S.; Grimwood, James M.; Alexander, Charles C. (1989). "This New Ocean - Chapter 12 - Mercury Orbits at Last". NASA. SP-4201. Archived from the original on June 23, 2021. Retrieved November 14, 2023.

- ^ "Long Stride To Manned Flight". The Evening Star. Vol. 109, no. 256. Cape Canaveral. Associated Press. September 13, 1961. Archived from the original on November 14, 2023. Retrieved November 14, 2023.

- ^ Brown, Dan (September 14, 1961). "Space Ship's on the Main Line--All the Way". Miami Herald - Indian River Edition. Vol. 51, no. 287. Cape Canaveral. p. 1B (61). Archived from the original on November 14, 2023. Retrieved November 14, 2023.

- ^ Grimwood, James M. (1963). Project Mercury: A Chronology (PDF) (Technical report). NASA. pp. 148–149. SP-4001. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 7, 2023. Retrieved November 14, 2023.

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.