Medicinal jar

A medicinal jar, drug jar, or apothecary jar is a jar used to contain medicines. Ceramic medicinal jars originated in the Islamic world and were brought to Europe where the production of jars flourished from the Middle Ages onward. Potteries were established throughout Europe and many were commissioned to produce jars for pharmacies and monasteries.[1] They are an important category of the Dutch and English porcelain known as Delftware.[2]

The jars were used by apothecaries in pharmacies and dispensaries in hospitals and monasteries.[3][4] Apothecaries needed containers to store herbs, roots, syrups, pills, ointments, spices and other ingredients used to make remedies as well as the medicines themselves.[1]

History

Earthenware storage jars for drugs have been found on archaeological sites in Turkey, Iran, Iraq, Greece and Rome.[5] The technology appears to have originated in Mesopotamia in 600–400 B.C.[6] A number of innovations occurred in Western Asia regarding pottery decoration, particularly the development of tin glazes to enable jars to contain fluids.[7] The tin glaze was believed to have originated in Mesopotamia in 600–400 B.C.[8] By the 12th to 13th centuries jars were lustreware which gave a sheen to the surface of the jars.[8]

Jars from Syria and Persia were taken to Spain from the 13th to 14th centuries after which Spanish and Italian potters began to manufacture jars.[6][9] The tin glaze technique which allowed decoration of the jars was known in Europe as maiolica, faience or delftware.[8] These different terms referred not to technical differences in the jars' manufacture but stylistic differences.[6]

The style of jar known as albarello also came from the Middle Eastern Islamic potters.[8][10] The albarello is cylindrical in shape usually with a narrow waist; it has a flange at the open end. A parchment cover could be tied over the flange to seal the contents.[8] Other jars were ovoid or globular in shape. Syrup jars had spouts and handles.[11] Other items used by apothecaries were dispensing and ointment pots, pill tiles and mortars.[11]

Potteries producing jars were located in Spain, France, Italy, Sicily, Switzerland, Germany, Austria, Belgium, Holland, Sweden, and Britain.[12]

Jars were widely used in Europe and Latin America at the beginning of the 19th century but during the 18th and 19th centuries production of glass storage bottles was increased.[13]

Animal, mineral and vegetable ingredients were stored in the jars.[14]

Vegetable ingredients included culinary herbs, fruits, roots, leaves, seeds, flowers, wood, oils, gums and resins.[14] Spices used for medicinal purposes included cassia bark, tamarind, nux vomica, senna, sandalwood, cloves and nutmeg.[5] These came from the Near East and later ingredients from the New World included copaiva balsam, sarsaparilla, tobacco, cinchona bark (quinine) and ipecacuanha.[14]

Some common animal products were contained, such as honey, butter, beeswax and chicken fat as well as more unusual ingredients including foxes' lungs, earthworms, scorpions, musk, ambergris and ivory.[15] Minerals used included precious stones and sulphur, mercury, antimony and other minerals.[15]

Collections

Medicinal jars are collected in the Wellcome Museum, Royal College of Surgeons and Royal Pharmaceutical Society in London, the Thackray Museum of Medicine in Leeds, Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia,[16] the Esteve Pharmacy in Llívia, Spain, the Pharmacy Museum at the University of Basel in Switzerland and the Pharmacy Museum, Jagiellonian University Medical College in Kraków, Poland.

Gallery

- Medicinal jars

- Syrian medicinal jars made circa 1300, excavated in Fenchurch Street, London, an example of Islamic contributions to Medieval Europe. Museum of London.

- Spanish albarello with two rabbits nibbling a grape vine, 14th century

- Italian two-handled "oak leaf" jar with male and female portraits, 15th century

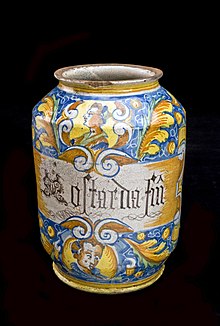

- Syrup jar for oil of foxes, Italy, 18th century

- Faentine albarello jar with white-bearded turbaned physicians and trophies of arms, 16th century

- Faentine jar with the head of a warrior, 16th century

- Italian jars showing St Matthew, 16th–17th century

- Dutch albarello jar, 17th century

- English jar for caryocostin, 17th century

- Spanish albarello used for cinchona bark, 18th century

- English delftware syrup jar, 18th century

See also

References

Citations

- ^ a b Drey 1978, p. 21-22.

- ^ Hudson 2006.

- ^ Finzsch & Jütte 1996, p. 67.

- ^ Drey 1978, p. 21.

- ^ a b Drey 1978, p. 22.

- ^ a b c Legge 1986, p. 12.

- ^ Drey 1978, p. 24.

- ^ a b c d e Drey 1978, p. 26.

- ^ Griffenhagen 2004, p. 5.

- ^ Campbell 2006, p. 7.

- ^ a b Legge 1986, p. 14.

- ^ Drey 1978, p. 20.

- ^ Griffenhagen 2004, p. 7–8.

- ^ a b c Legge 1986, p. 10.

- ^ a b Legge 1986, p. 11.

- ^ Hudson 2006, p. 8.

Bibliography

- Campbell, Gordon (2006). The Grove encyclopaedia of decorative arts. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195-189-483.

- Drey, Rudoph E.A. (1978). Apothecary Jars: pharmaceutical pottery and porcelain in Europe and the East 1150–1850. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-09965-3.

- Finzsch, Norbert; Jütte, Robert (1996). Institutions of Confinement: Hospitals, Asylums, and Prisons in Western Europe and North America, 1500-1950. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521534488.

- Griffenhagen, George (2004). "Evolution of Drug Containers" (PDF). Apothecary's Cabinet (8): 5–8. PMID 15190917.

- Hudson, Briony (2006). "English Delftware Drug Jars: The Collection of the Museum of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain". Journal of the History of Collections. 18 (2): 290–291. doi:10.1093/jhc/fhl032.

- Legge, Margaret (1986). The Apothecary's Shelf: drug jars and mortars 15th to 18th century. National Gallery of Victoria. ISBN 0-724-101179.