Martha Washington Hotel

| Martha Washington Hotel | |

|---|---|

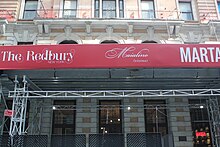

The original entrance and street-level facade on 30th Street in 2011 | |

| |

| Former names | Hotel Thirty Thirty, Hotel Lola, King & Grove New York, The Redbury New York |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Renaissance Revival |

| Location | 30 East 30th Street, New York, NY, 10016 |

| Coordinates | 40°44′41″N 73°59′04″W / 40.74472°N 73.98444°W |

| Construction started | 1901 |

| Opening | March 1, 1903 |

| Owner | 29 East 29th Street NY Owner, LLC[1] |

| Management | CIM Group |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 13 |

| Floor area | 143,000 sq ft (13,285 m2) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Robert W. Gibson |

| Developer | Woman's Hotel Company |

| Other information | |

| Number of rooms | 250 |

| Website | |

| Official website | |

| Designated | June 19, 2012 |

| Reference no. | 2428[2] |

The Martha Washington Hotel (later known as Hotel Thirty Thirty, Hotel Lola, King & Grove New York, and The Redbury New York) was a hotel at 30 East 30th Street (later 29 East 29th Street) in the NoMad neighborhood of Manhattan in New York City. Opened in 1903 and operated as a women-only hotel for 95 years, the 13-story structure was designed by Robert W. Gibson in the Renaissance Revival style for the Women's Hotel Company. The hotel's namesake, Martha Washington, was the first First Lady of the United States. It is a New York City designated landmark.

The facade is largely made of brick and stone and contains classical design elements such as brackets, dentils, ornate lintels, quoins, and rustication. On both 29th and 30th Streets, the facade is divided vertically into seven bays and horizontally into a two-story base and ten-story upper section, with a recessed top floor. The hotel originally contained several amenity areas for guests on the lower two stories, including a lobby, dining rooms, reception rooms, and ballroom. Generally men were only permitted to enter the ground-level spaces and some of the second-story spaces. The upper stories originally contained 200 short-term guest rooms and 400 long-term residences, which were downsized to 250 hotel rooms by the 2020s.

The Woman's Hotel Company was established in 1897 and sought to identify a site and raise money over the following four years. Construction began in mid-1901, and the Martha Washington Hotel opened on March 1, 1903, as both a hotel and a long-term residence. Though there was initially high demand for the Martha Washington's rooms, the hotel's owners struggled to raise money and leased it out beginning in 1907. The Manger family operated the Martha Washington from 1920 to 1948, and the Sillins Hotel Corporation operated the hotel from 1950 to 1997. The hotel was converted to a mixed-sex tourist hotel in 1998 and, after a renovation, was renamed the Thirty Thirty in 2000. The hotel was further renovated in 2011, 2014, 2016, and 2019, undergoing several name and ownership changes during that decade. As The Redbury New York, it saw decreased patronage during the COVID-19 pandemic and became a temporary shelter for migrants in 2023.

Site

The Martha Washington Hotel is located at 27–31 East 29th Street in the NoMad neighborhood of Manhattan in New York City.[2] The hotel occupies the center of a city block bounded by Madison Avenue to the west, 30th Street to the north, Park Avenue South to the east, and 29th Street to the south. The land lot is rectangular and measures 14,812 square feet (1,376.1 m2), with frontage of 75 feet (23 m) on 29th and 30th Streets and a depth of 197.5 feet (60.2 m).[1] Nearby buildings include the Church of the Transfiguration, Episcopal and the James New York – NoMad to the west, the Emmet Building and 30 East 29th Street to the south, and the Colony Club building to the north.[1][3] The site was assembled in 1901 from two land lots that had been occupied by the American Female Guardian Society since 1856.[4]

Architecture

The Martha Washington Hotel was designed by architect Robert W. Gibson[5] in the Renaissance Revival style.[6] At the time of the hotel's construction in the early 1900s, many hotels were being built with classical architectural features because they had been designed by architects trained in Europe. Gibson, who had trained in England, incorporated classical elements such as brackets, dentils, ornate lintels, quoins, and rustication into the design.[6]

Facade

The two primary elevations of the facade, on 29th Street to the south and 30th Street to the north, are very similar to one another. Both elevations rise twelve stories from the ground and are divided vertically into seven bays;[7] the top stories are recessed from the street.[8] The western elevation is partially visible and is made of plain brick with one-over-one sash windows, a recessed exterior light court, and a metal-sheathed section near the top.[9]

Lower stories

The ground floor and second floor piano nobile of both elevations are clad in rusticated blocks of limestone.[10] A string course runs above the ground floor on both elevations. On 30th Street, each of the ground-floor bays is separated by a pier with alternating tan brick and limestone.[7] The entrance on 30th Street is in the center bay, and there are double-height storefronts on either side. The entry doors are made of glass and metal and are topped by a glass transom window. Two of the outer bays feature marble stoops with metal railings that ascend to the storefronts.[10] The ground floor on 29th Street is similar in design except that the entrances are in the outermost bays. The 29th Street entrances are flanked by pairs of rusticated columns, which support a pediment with a centered cartouche and a finial.[9]

On both elevations, the second-story piano nobile is clad with brick and contains stone quoins around the windows. The three center windows of the second story have stone balustrades at their bottoms, as well as round arches with keystones at their tops. The four outer windows on that story contain rectangular openings surrounded by terracotta key patterns. The lowest parts of the outer windows are clad with stone panels, while the upper sections are topped by lintels with splayed keystones. Above the second story are protruding balconettes with iron railings, which are supported by terracotta brackets.[10]

Upper stories

Each window in the third through eighth stories of the northern and southern elevations has a terracotta frame. The outermost bays of the facade are clad with brick, which is arranged to resemble a rusticated facade. The center three bays feature horizontal stone courses at regular intervals, and the middle bay contains three-part windows, some of which are arranged as Palladian windows. The remaining bays have stone windowsills and are topped by lintels with key or splayed patterns. There are decorative spandrel panels above the three central third-story windows, and there are terracotta lunettes above the five central fourth-story windows.[10]

On the ninth story of both elevations there are balconettes with iron railings in front of the outermost bays and the three center windows. All of the ninth-story windows have terracotta lintels. On the tenth story the windows are rectangular and have lintels with splayed patterns. Above the tenth-story windows are keystones with brackets, as well as terracotta corbels, above which runs a horizontal terracotta string course. The eleventh story contains a facade of terracotta panels, interspersed with windows; there is a large cornice above the eleventh story, with modillions and dentils. There are terracotta panels on the twelfth story.[10]

Interior

When the hotel first opened it contained advanced mechanical equipment for its time, such as elevators, mail chutes, steam heating, and electric lighting.[11][12] Every room had natural light exposure; the hotel did not have any interior light courts.[8][13] Visitors of any sex could use the telegraph, telephone, or messenger services.[13] There were also exterior fire escapes and stairwells.[14] As of 2023, the hotel contains about 143,000 square feet (13,300 m2) of space, spread across 13 stories.[15]

Public rooms

When the Martha Washington Hotel was built the first and second floors were dedicated to communal rooms such as offices, a restaurant, dining rooms, and reception rooms.[16] The lobby was decorated in an colonial style, with leather chairs and a buff-and-white color scheme.[8][17] While the restaurant was open to the general public, there were dining rooms that could only be used by guests and residents.[11] There were several shops, including a milliner/tailor shop, manicurist/podiatrist, shoe shiner, drug store, and newsstand.[11][12] Next to the restaurant was a writing room and waiting room for men.[13] Over the years, various spaces in the lobby were carved out to make way for storefronts.[18]

Following a 2000 renovation, a bar and restaurant were created off the lobby.[19] During a renovation in 2011, the hotel's ground floor was gutted, the ceiling was raised, a large glazed-ebony door was installed,[20] and the walls were redecorated with black-and-white photographs of women.[21][22] After the Martha Washington was renovated again in 2014, a new meeting and event space covering 4,000 square feet (370 m2) was created within the hotel.[23] The public spaces were repainted in walnut colors, with fluted columns and blue floor tiles.[24][25] There was also a long hallway, with mid-century modern furniture, leading to a check-in desk.[25] The current design of the lobby as of 2023 dates to a 2019 renovation, which added seating areas enclosed with stained-glass panels, as well as blue-tinted lighting and rounded mirrors. There is also a lobby lounge next to the elevators near the entrance.[26] The hotel has a fitness center as well.[27][28]

The second story had a tenant-only dining room, as well as several private reception rooms, when the hotel opened in 1903.[13][17][29] Some of the reception rooms could be combined for major events.[8] The second floor also had a library patterned after the one in George Washington's estate, Mount Vernon,[12][16] with a "handsome" fireplace and a bas relief of the United States' first First Lady, Martha Washington.[16][8] The library was decorated in a deep-red color scheme and ornamented with dark wood.[8] The parlors, music rooms, tea rooms, and other spaces were designed to fit women's tastes.[12] By 2016, the second floor included a ballroom covering 2,700 square feet (250 m2) as well as a terrace of 1,700 square feet (160 m2).[30] The roof of the hotel contained a terrace that could be converted into a "summer garden and promenade" with awnings and hammocks.[8][31]

Guest rooms

Originally the top ten stories of the hotel comprised about 200 short-term guest rooms and 400 long-term residences,[16] starting at the third floor.[13] These were available in both single-room and multi-room en suite configurations.[11][16][32] Each story held between 40 and 50 units[8] and had a reception room.[16][29] The 12th floor contained employee bedrooms, while the remainder of the 12th story and the inhabitable portions of the 13th story contained studios with skylights.[8] By the late 1990s, the Martha Washington had been divided into either 423[33] or 469 rooms.[14]

When the hotel first opened about 36 women lived on each floor, with four communal toilets and four bathtubs on each floor.[31] There was approximately one bathroom for every four guest rooms;[17] most units lacked en suite bathrooms.[33] The guest rooms were arranged so they could easily be combined into suites with two to five rooms. Some apartments were outfitted with double doors, allowing businesswomen to use these spaces as showrooms. Each bedroom had furnishings such as damask coverings and large pillows, and the hotel as a whole had custom-designed furniture such as double-faced bookcases, as well as appliances such as electric alarms.[8] Smaller rooms had sofa beds, while larger units contained standard beds.[13]

When the Martha Washington was renovated into a co-ed tourist hotel in 2000 the rooms were rearranged. Sources disagree on whether the hotel had 370,[33] 350,[34] or 262 units.[19] The rooms were small and plain in design;[19][35] a Washington Post critic described the rooms as having a bed, two side tables, an armoire, and a small dressing area.[36] Some rooms also retained vestiges of the hotel's original use: for example, some guest rooms had sinks but not toilets or bathtubs.[19] By 2016, there were around 255 rooms,[27][37] many in different sizes and layouts.[27][38] The rooms were decorated in a red, gray, black and white color scheme.[25] with motifs relating to music and 20th-century New York City history.[37] Each room was also equipped with mirrors, small television sets and refrigerators, and hidden speakers.[27] Desks, nightstands, minibars, and other furniture were added in 2019, and the hotel's 259 rooms were redecorated with gray walls.[26]

History

There was demand for women's residences in New York City as early as the mid-19th century, when most unmarried women lived in boarding houses or at home.[39] Among the earliest women's residences in the city were the Working Women's Home at 45 Elizabeth Street, developed in the 1850s, as well as a women's hotel developed by A. T. Stewart on Park Avenue, developed in 1869.[40][41] Through the 19th century, most of the city's hotels refused to admit single women at night.[41] Between 60,000 and 70,000 businesswomen lived in the city by 1899,[41][42] when philanthropist Grace Hoadley Dodge estimated that 10,000 women needed a women's hotel.[43] When the Martha Washington Hotel was being developed in 1901, a "woman prominent in sociological work" said that nine out of ten working women lived apart from their families.[44]

Development

The Woman's Hotel Company was established in 1897[45] by Charles Day Kellogg, a member of the Charity Organization Society, which was created specifically to erect hotels for businesswomen.[41][46] The hotel was intended as a business enterprise rather than as a philanthropic venture.[12][41] The company issued a prospectus in January 1898 and appointed a board of directors,[45] composed of two women and six men.[13] The next month, the Woman's Hotel Company began selling 10,000 shares at $100 each.[47][48] The firm wished to build a 10- to 12-story hotel in Manhattan with 500 rooms;[42] the company believed that the hotel could pay a 5 percent annual dividend and earn at least $150,000 per year, which could be used to fund the development of other hotels.[49] In addition, the rooms were to be rented to "self-supporting women" such as artists, teachers, authors, and clerks,[50] who were to pay between $3 and $8 a week.[51] Although enough women expressed interest in the hotel to fill it to capacity before it opened, the Spanish–American War and slow fundraising delayed the hotel's construction.[4] The company wanted to raise $400,000 but had obtained only $150,000 by October 1899,[52] which rose to $200,000 by the last week of December.[53]

Two hundred fifty prominent New Yorkers,[13] including William Colford Schermerhorn, John D. Rockefeller, Olivia Sage, and Helen Gould, contributed to the Women's Hotel Company's fundraising effort,[4] which had raised $300,000 by the beginning of 1900.[51][54] When the Women's Hotel Company was incorporated in March 1900, a building committee was appointed to review potential sites;[55] subscriptions had reached $350,000 by that June.[56] The company announced in September that it had identified a site near Madison Avenue.[57] In January 1901, it acquired the Female Guardian Society's building at 29 East 29th Street (just east of Madison Avenue), extending through the block to 30th Street.[58][59] The firm planned to begin construction in June 1901, when the society's lease expired, and to finish the hotel by late 1902.[60]

Robert W. Gibson was hired as the architect in April 1901,[61][62] following an architectural design competition.[4] Gibson filed plans for the hotel in June, with an estimated cost of $350,000.[63][64] The Louis Weber Building Company was hired as the general contractor,[65] while John W. Rapp received a fireproofing contract.[66] By September, the existing structures on the hotel's site had been demolished.[67] At the end of 1901, the Woman's Hotel Company announced that the hotel would be named after Martha Washington.[68][69] James Case was hired as the hotel's manager.[16][69] The contracts for decorating the guestrooms were awarded to Molka Kellogg, the daughter of Charles Kellogg, along with Clara Davidge, the daughter of Episcopal bishop Henry C. Potter.[70] All work was complete by February 5, 1903, when hotel officials planned to open the guestrooms for public inspection; the structure had cost $800,000 to complete. The formal opening was initially set for February 15.[16][29]

Operation as women's hotel

The Martha Washington Hotel opened on March 1, 1903,[71] serving both long-term residents and short-term guests; it aimed to attract a white and middle-class clientele.[72] At opening, there were 500 residents and 250 temporary guests,[17] and the waiting list had 200 names.[11][29] Daily fees for single rooms ranged from $1 to $2,[73] while weekly rent for apartments was between $3 and $17.[17][29][71] Unmarried women could rent rooms from day-to-day or for longer terms, with an average rent of $1.50 per day.[31] Guests could also pay $6 per week for unlimited meals under what was known as the "American plan".[17][71] Men and married women were allowed to use the restaurant and drawing rooms on the lower stories but could not rent rooms.[16] This policy applied even to residents' close relatives, such as brothers and fathers,[8] as well as men invited by the residents.[12][13] Also banned from the hotel were pets,[74] babies,[75] and any tenant who was involved in a breach of promise lawsuit, since such suits attracted publicity that the hotel's managers did not want.[76]

Originally, the hotel employed male bellhops and elevator operators, as the managers felt that women could not physically carry luggage.[29] The mail clerk and the 15-member cooking team were also men,[74] but the hotel also had waitresses and female clerks, bookkeepers, and cashiers.[16][29][77] The hotel hired 50 waitresses and 30 chambermaids initially,[29][77] although male waiters were hired in 1903.[78] Early guests hailed from across the United States and from Europe.[12] An article in the Star-Gazette described the Martha Washington's clientele as including "a large number of literary women", as well as students, a YWCA manager, painters, advertisers, and accountants.[79]

1900s to 1920s

Shortly after the Martha Washington opened, Helen Gould lent 55 paintings and 7 sculptures to the hotel for decoration.[80] Initially, guests failed to tip the waitresses, leading to a strike in mid-1903;[81] tipping was banned completely the next June.[82] The Martha Washington also originally banned liquor sales,[13][83] though some tenants were requesting the addition of a bar by early 1904.[84][85] The novelty of an all-female clientele prompted one person to write to The New York Times, complaining about the presence of "observation automobiles" near the hotel.[31] Delays in the hotel's construction had forced the hotel's directors to cover initial expenses using their own money; by January 1904, they reported that the hotel's only income came from short-term guests.[11] The Martha Washington hired its first female elevator operator in early 1904;[86] that year, the hotel replaced the bellboys with female bellhops[87][82] and fired the male waiters.[88]

After the minimum room rate was raised to $12 per week in late 1905, the New-York Tribune said that "the last touch of philanthropy has disappeared from the Martha Washington".[89] The hotel was profitable by 1906,[11][90] when its directors decided to discontinue the "American plan" meals due to low patronage.[11][91] Internal disputes prompted the Martha Washington's directors to consider leasing the hotel out during late 1906;[91][92] some dissenters, including Charles Kellogg's daughter Lucy, wanted to assume the hotel's management.[90][93] At the time, the Women's Hotel Company had not paid a dividend in five years, and there were disagreements over expenses.[90] In January 1907, Arthur W. Edgar[a] leased the hotel for 10 years.[90][94] Edgar agreed to pay $507,000, continue operating the hotel for women only, and rent at least 25 rooms for no more than $1 a day.[94]

According to the 1910 United States census, residents were generally well-off with a median age of between 45 and 50.[31] Edgar operated the hotel until his death in 1911,[95] and George C. Brown operated the hotel for the next decade.[96] By then, more New Yorkers had come to understand the concept of a women's hotel.[7] The Martha Washington switched to a staff of all-female elevator operators in 1917.[31] A group of investors offered $800,000 for the Martha Washington in January 1920,[97] and William and Julius Manger of the Bell Apartment Hotel Company bought the hotel the same month.[98][99] The Northern Hotel Company held a long-term lease on the hotel at the time,[97][99] but the company subleased the hotel to the Mangers that March.[96][100] The Mangers jointly operated the Martha Washington until William's death in 1928, upon which William's share in the hotel was transferred to his brother and to a trust fund created for his relatives.[101][102]

1930s to 1960s

By 1930, an auditor for the Bell Securities Company, the holding corporation that owned the hotel, had said that the Martha Washington's future was "extremely limited" because of decreased salaries and profits.[103] The Boone Securities Corporation, a subsidiary of Manger Hotels,[104][105] bought the hotel at an auction in 1933, bidding $10,000 and taking over a $450,000 mortgage.[106][107] Later the same year, the hotel's general manager E. J. Carroll obtained a liquor license, allowing the Martha Washington to serve wine.[108][109] The issuance of the liquor license had come at the end of Prohibition,[110] amid an increase in the number of women who wished to drink wine.[108][109] Julius Manger continued to operate the Martha Washington by himself until his death in 1937.[111] John B. Campbell, the Martha Washington's longtime "house mother", estimated in 1949 that he had served three million women during the preceding 22 years.[112]

Julius Manger's son, Julius Manger Jr., sold the Martha Washington and two adjoining low-rise buildings in February 1948 to a syndicate represented by Schiff, Dorfman, Stein, and Brof. The buyers quickly resold the hotel to its managing director Edward Tilson and hotelier Sol Henkind. At the time, the hotel had 445 guest units, a restaurant, and five stores, while the adjacent buildings included four apartments, three stores, and some dormitories.[104][105] The Sillins Hotel Corporation, led by Robert B. Sillins, bought a controlling stake in the hotel in 1950 and continued to rent its 450 rooms to women. Sillins planned to sand-blast the facade and renovate the lobby for $200,000, and he hired the Bell Maintenance Company to renovate the entrance.[113][114] The hotel's operators took out a $100,000 mortgage loan in 1953.[115]

Dick McCarthy and Joseph Rauti of Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, opened a restaurant called the Colonnade Room at the hotel in 1961. The restaurant, seating 250 guests, contained a cocktail lounge.[116] A nightclub called the High Life Room opened at the hotel in April 1967.[117] The nightclub, described as looking "somewhat like a Moorish courtyard", was placed within the hotel's former ballroom.[118]

1970s to 1990s

By the early 1970s, the Martha Washington was one of four women's hotels in the city, along with the Allerton Hotel for Women, Barbizon Hotel, and East End Hotel. The Martha Washington's clientele consisted mostly of students and young professionals, and its occupancy rate averaged 80 to 90 percent.[119] The hotel enforced a nighttime curfew, employed security guards, and banned male guests above the lobby.[119][120] A limited number of men, such as residents' fathers and doctors, could enter the upper stories with supervision.[119] Due to the ban on male visitors, women generally felt safe sleeping even with their doors unlocked. Nonetheless, there were still some reports of illicit activities in the late 20th century, including allegations that employees stole from residents and that prostitutes were using the exterior staircases to conduct business.[14]

The New York City government enacted a law in 1970 that banned gender discrimination in public places,[121] and the city's Human Rights Commission ruled in 1972 that hotels were not exempt from this law.[122][123] As such, the city ordered the Martha Washington to start accepting male guests beginning in 1973.[123][124] Amid opposition from figures such as New York City Council president Sanford Garelik,[125] the New York City Council later passed an amendment exempting single-sex residential hotels from the law.[126] Occupancy had declined to 65 percent by 1979. The New York Times described the lobby as "dark and drab", having been downsized to make way for stores, and the bedrooms as having "chipping paint and worn bedspreads".[18] By then, the hotel's owner Martha Washington Associates was spending $500,000 to repair the property, and most residents were still relatively young, being between 25 and 40 years old.[18]

In 1982, the Chicago Tribune described the hotel as having 451 rooms and a female manager, although it did hire some male staff such as bellhops, clerks, and engineers.[120] At the time, there was high demand for the hotel; its manager Janis Algar said that "a lot of women from out of town don't know the neighborhoods and are reluctant to take an apartment right away".[127] The first-floor ballroom hosted the Danceteria nightclub, which opened in May 1991[128] and operated until 1993;[129][130] during this time, there were many reports of illegal drug use.[14] Afterward, the Danceteria space was converted into a club called the Melting Pot, which had three bars,[131] then became a mosque by 1998.[14] Toward the end of the 20th century, the Martha Washington functioned as a single room occupancy building.[14][132] It had been among the last women's hotels in Manhattan that were unaffiliated with a house of worship or a school.[14] The owners had failed to pay taxes for several years and owed $160,000 in back taxes by 2000.[133][134]

Operation as co-ed hotel

Late 1990s to early 2010s

Property Markets Group (PMG) bought the Martha Washington and Allerton hotels from Sillins in 1997.[14][135] The group, which paid around $18 million for the Martha Washington, announced plans to convert it to a co-ed tourist hotel,[14][33] saying the hotel was "underused".[135] At the time, three-fourths of the bedrooms were empty, and most had no bathrooms.[33] The hotel closed for renovations in August 1998 and stopped accepting new guests, although 153 long-term residents were allowed to remain there.[135] The Martha Washington began accepting male guests that October.[14] Many existing female residents objected, with one resident calling the new policy "a rapist's dream" because men could crawl into residents' bathrooms through the fire escapes.[14] By the end of 1998, the Martha Washington was a standard tourist hotel;[136] it was one of several residential hotels in the city that had been converted into tourist hotels at the end of the 20th century.[137]

PMG undertook further renovations in 2000, spending about $49 million to upgrade the hotel. Kevin Maloney of PMG agreed to upgrade 83 tenants' rooms and allow them to continue paying the same rental rate if they endorsed a certificate of no harassment, which was required for the hotel. Another 37 tenants opposed the conversion and filed a lawsuit, claiming Maloney harassed them; despite this, Maloney received the certificate of no harassment and did not offer the dissenting tenants anything.[33] Some residents protested against the renovations in 2000, claiming that PMG was disrupting their water and heat service and that there were construction hazards.[138] Citylife was operating the hotel by 2000, with PMG as the owner,[35][139] and continued to renovate the hotel through the end of that year.[35][140] The group rebranded the Martha Washington as the Hotel Thirty Thirty in July 2000, a reference to the hotel's address at 30 East 30th Street,[141] though media sources had reported on the new name as early as the preceding October.[142]

The Thirty Thirty initially operated as a budget hotel and still had about 90 long-term residents by 2003.[34] Rockpoint Group bought a majority stake in the hotel from PMG in 2006.[23][143] During the mid-2000s, the Thirty Thirty operated as a medium-priced hotel with 253 rooms.[144] The hotel was closed in 2011 for renovations, reopening that December.[21][145] At that time, it was renamed the Hotel Lola, after a fictional character created by the renovation's designer Susan Jaques;[20][21] this character was based partially on the 19th-century entertainer Lola Montez.[145] The renovation cost $15 million,[20] of which $12 million was funded by a loan issued by Citigroup Commercial Mortgage Trust.[146] The hotel was divided into 276 rooms,[21] which were designed in a minimalist style.[22]

Early 2010s to present

King and Grove Hotels bought the Hotel Lola for $116 million from Rockpoint Group in June 2012[143][147] and renamed it the King & Grove New York shortly thereafter.[147] King & Grove CEO Ed Scheetz and Chetrit Group co-owned the hotel until 2013,[148] when Scheetz took over five of the partners' 14 properties, including the King & Grove New York.[149] Danny Meyer announced in October 2013 that he would open a restaurant at the King & Grove New York,[150][151] and he outlined plans the next year for a wood-fired pizzeria.[152][153] Scheetz announced in May 2014 that King & Grove would be rebranded as Chelsea Hotels and that the King & Grove New York would be renovated and renamed back to the Martha Washington Hotel.[154][155] Scheetz said he "wanted the hotel to be more upscale",[156] and he hired Annabelle Selldorf to redesign the interiors.[23][24] The $20 million project involved renovating all of the hotel's rooms, adding space for three restaurants, and moving the main entrance to 29th Street. By then, the hotel still had about 50 residents.[156]

The renovation was completed in September 2014,[23][30] and the Marta pizzeria opened later that year.[157][158] Chelsea Hotels placed the Martha Washington up for sale in March 2015.[159] The hotel was sold that November for $158 million to CIM,[160][161] which planned to rebrand the hotel as the Redbury New York following a second renovation.[162] The following year, CIM renamed the hotel the Redbury New York, and hospitality group SBE took over the hotel's management.[37][163] Dakota Development and Avenue Interiors redesigned the guest rooms.[164] The hotel was themed to the music of the nearby Tin Pan Alley and the history of the NoMad neighborhood.[37] The first rooms reopened in April 2016,[37] and the hotel was fully reopened that October under the Preferred Hotels & Resorts brand.[164][165] The Redbury's managers hired local firm Home Studios to redesign the lobby and rooms in mid-2019.[26][166]

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City in early 2020, the Redbury began serving medical professionals.[167] The hotel was otherwise closed to the general public for much of 2020,[168] but patronage did not fully recover after pandemic-era restrictions were lifted.[15] Danny Meyer moved his Maialino restaurant to the Redbury in late 2022.[169][170] In August 2023, the New York City government began to use the hotel as temporary migrant housing, amid a citywide migrant housing crisis caused by a sharp increase in the number of asylum seekers traveling to the city.[171][172] At the time, there were 250 rooms;[172][173] the hotel began accommodating families with children, and it stopped accepting reservations.[174] Danny Meyer closed his restaurants at the Redbury that month,[175][176] citing delays in the full reopening of the hotel[177] and the migrant crisis.[15]

Notable people and tenants

The poet Sara Teasdale stayed at the hotel during her New York visits from 1913 onward, and actress Louise Brooks relocated there from the Algonquin Hotel.[7][178] The editor Louise E. Dew was a resident as well.[7] Jean H. Norris, the first female magistrate in New York state, also lived in the hotel in the early 20th century.[31] Although a 10-room suite at the hotel was renovated for socialite Consuelo Vanderbilt in 1907,[179] she never lived there.[31] Veronica Lake, one of Hollywood's most prominent actresses in the 1940s,[180] was found to be working as a barmaid at the Martha Washington in 1962.[181][182] After the story was published, several people offered Lake money and jobs in the entertainment industry, which she refused;[183] Lake eventually was able to obtain other acting roles.[184] The writer and public speaker Fran Lebowitz stayed at the hotel for two months when she first moved from New Jersey to New York in 1969.[185]

From the 1900s onward, the hotel served as the headquarters of the Interurban Women's Suffrage Council,[7][178] the International Federation of Business Women,[186] and the Committee on Women's Work of the Republican National Committee.[187] In subsequent years, the hotel also hosted organizations such as the American Gold Star Mothers in the 1940s.[188]

Impact

When the Martha Washington opened, Catherine King of the New York World wrote that "when you go in ... you are instantly reminded of a Martha Washington fichu" and that the hotel was "a sort of beautiful, well-behaved haven where the women who now languish in boarding houses and haven't quite compassed apartments can go to live—and more".[74] The hotel's exclusivity led The Christian Science Monitor to liken the Martha Washington to a women's club in 1910.[189] The hotel was not noted for its design; architectural critic Christopher Gray wrote in 2012 that "the Martha Washington certainly does have a 'special character'—a requirement for landmark designation—even if that character lies in its history, not its architecture."[31]

After the hotel was renamed the Thirty Thirty in 2000, a Washington Post critic wrote that the hotel was hard to find despite its new name, the staff were confused, and the hotel as a whole was "rough-hewn".[36] The critic described the lobby as "well polished" but said that the guestrooms were only "slightly larger than a janitor's closet [and] are awash in the brown/green side of the Crayola box".[36] Following the 2011 renovation, a critic for ABC News wrote: "We find the check-in process disorganized and the modern minimalist room, with gray carpeting and no pictures on the wall, stark and sterile. And our tiny bathroom is unheated."[22] When the Redbury opened in 2016, The Telegraph praised the hotel's central location and food service, but criticized the styling and said the Redbury "is a bit short on amenities".[27] U.S. News & World Report stated that "the hotel features a contemporary ambiance with updated guest accommodations sporting a chic new look".[28]

The hotel building was also depicted in an opening scene for the 1967 movie Valley of the Dolls.[7][140] The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission designated the hotel as a city landmark on June 19, 2012,[190] and the hotel was inducted into Historic Hotels of America, an official program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, in 2016.[191] Additionally, the National Collaborative for Women's History Sites, in collaboration with the William G. Pomeroy Foundation, placed the hotel on the National Votes for Women Trail in 2022.[192]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ The New-York Tribune spelled his name "Eager",[94] though Landmarks Preservation Commission 2012, pp. 7–8 spells it "Edgar".

Citations

- ^ a b c "30 East 30th Street, 10016". New York City Department of City Planning. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 2012, p. 1.

- ^ "Discover New York City Landmarks". New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Archived from the original on March 17, 2023. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Landmarks Preservation Commission 2012, p. 5.

- ^ Placzek, Adolf K. (1982). Macmillan Encyclopedia of Architects. Free Press. p. 200. ISBN 978-0-02-925000-6. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 2012, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e f g Landmarks Preservation Commission 2012, p. 8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Woman's Hotel Opens: Two Hundred Names Already on the Waiting List". New-York Tribune. February 4, 1903. p. 7. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 571344633.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 2012, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e Landmarks Preservation Commission 2012, pp. 8–9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Landmarks Preservation Commission 2012, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bowdoin 1903, p. 1492.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Woman's Hotel is Now a Fact". Democrat and Chronicle. March 14, 1903. p. 9. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Lobbia, J. A. (November 17, 1998). "Martha Washington goes coed". The Village Voice. p. 26. ProQuest 232262276. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 21, 2023.

- ^ a b c Hughes, C. J. (August 21, 2023). "Two Danny Meyer restaurants in NoMad to close as their hotel home becomes a shelter for migrants". Crain's New York Business. Vol. 39, no. 29. p. 2. ProQuest 2856473888.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Hotel for Women Only: the Martha Washington Soon to Be Opened in New York". The Sun. February 5, 1903. p. 5. ProQuest 536640360.

- ^ a b c d e f "Women's Hotel Real Paradise: the Guests Number 500 and So Far Not a Complaint Heard". St. Louis Post – Dispatch. March 29, 1903. p. 6. ProQuest 579618688.

- ^ a b c Daley, Suzanne (November 25, 1979). "A Simple Success Story: The Last Women's Hotels". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 16, 2023. Retrieved February 16, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Pielou, Adriaane (November 15, 2003). "New York Autumn Bargain Hotels". The Daily Telegraph. p. 7. ProQuest 317813313.

- ^ a b c "Design Hunting With Wendy Goodman — Previewing the New Lola Hotel – New York Magazine". New York Magazine. April 10, 2019. Archived from the original on March 23, 2023. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Johnson, Mary (December 27, 2011). "Hotel Lola Brings Glamour to Former Women's Residence". DNAinfo New York. Archived from the original on May 28, 2023. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Amorous Manhattan: Escape to the city that never sleeps". ABC News. February 10, 2012. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Jones, David (September 24, 2014). "Famed Martha Washington Hotel back in business". The Real Deal. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 16, 2023.

- ^ a b Bobb, Brooke (August 18, 2014). "Now Booking—A Ladies' Hotel Open to All". T Magazine. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 16, 2023.

- ^ a b c "The Redbury New York Review: What To REALLY Expect If You Stay". Oyster. October 1, 2015. Archived from the original on February 7, 2023. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ a b c "The Redbury New York Reimagined". Hospitality Net. October 24, 2019. Archived from the original on January 17, 2021. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "The Redbury New York". The Telegraph. June 7, 2017. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ a b "The Redbury New York Reviews & Prices". U.S. News Travel. Archived from the original on January 23, 2021. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Hotel for Women Only; Accommodations for 650 in the Martha Washington. Business and Professional Women as Stockholders and Tenants of the Structure". The New York Times. February 3, 1903. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ^ a b Rosenberg, Zoe (November 17, 2014). "NYC's Oldest Women's Hotel Now Has Men, New Makeover". Curbed NY. Archived from the original on June 1, 2023. Retrieved September 16, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Gray, Christopher (June 28, 2012). "For Career Women, a Hassle-Free Haven". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 28, 2019. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ Bowdoin 1903, pp. 1491–1492.

- ^ a b c d e f Oser, Alan S. (February 27, 2000). "New Landlord, Old Tenants, Hard Questions". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 1, 2015. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ a b Diop, Julie Claire (June 23, 2003). "'Carpet' Neighborhood Goes Upscale". Newsday. p. A25. ISSN 2574-5298. ProQuest 279689539.

- ^ a b c Shea, Barbara (November 19, 2000). "Grand Openings in NYC". Newsday. p. E10. ISSN 2574-5298. ProQuest 279399613.

- ^ a b c "New New York Boutique Hotels". The Washington Post. April 15, 2001. p. E03. ISSN 0190-8286. ProQuest 409099774.

- ^ a b c d e "The Redbury New York Hotel Opens". Hotel News Resource. April 13, 2016. Archived from the original on October 28, 2022. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ Ramani, Sandra. "The Redbury New York". NYMag.com. Archived from the original on November 1, 2018. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 2012, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Cromley, Elizabeth Collins (1990). Alone Together: A History of New York's Early Apartments. Cornell University Press. pp. 112, 114. ISBN 978-0-8014-8613-5. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Landmarks Preservation Commission 2012, p. 4.

- ^ a b "A Hotel for Women". The Washington Post. February 24, 1901. p. 31. ISSN 0190-8286. ProQuest 144282306.

- ^ "The Proposed Woman's Hotel". New-York Tribune. December 11, 1899. p. 5. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 574691011.

- ^ "Need of Women's Hotels". The Sun. July 21, 1901. p. 20. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 2012, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Hamersly, Lewis Randolph (1904). "Charles Day Kellogg". Who's who in New York City and State. Cornell Library New York State Historical Literature. L.R. Hamersly Company. p. 341. Archived from the original on November 14, 2012. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ "The Woman's Hotel Company; Stock Subscription Lists Opened Down Town". The New York Times. February 17, 1898. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 16, 2023.

- ^ "Go for Big Prices.: Second Night of the Sale of Stewart's Pictures". Chicago Daily Tribune. February 5, 1898. p. 1. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 172826636.

- ^ "Woman's Hotel Company: in the New Building Special Attention Will Re Paid to Ventilation". New-York Tribune. February 25, 1898. p. 5. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 574398326.

- ^ "Housing Women Workers: Will Hotels or Apartments Give the More Comport? A Plea From a Working Girl for Her Own Home—what Large Cities Are Doing to Further the Demand New-york Not Behind a Woman's Hotel London Also Interested". New-York Tribune. September 11, 1899. p. 7. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 574660649.

- ^ a b {{cite magazine|title=New York's Woman's Hotel |work=Harper's Bazaar |volume=4 |issue=8 |date=February 23, 1901 |page=524-525 |id=ProQuest 1914165708}]

- ^ "Women's Hotel.: Over One-third of the Capital Stock Subscribed to Date". Los Angeles Times. October 12, 1899. p. 3. ISSN 0458-3035. ProQuest 163936980.

- ^ "The Woman's Hotel: Remaining Stock Must Be Subscribed for This Week". New-York Tribune. December 28, 1899. p. 5. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 574684647.

- ^ "Women's Hotel Fund Completed". New-York Tribune. January 2, 1900. p. 5. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 570779176.

- ^ "Woman's Hotel Company.: Sufficient Money Raised to Build Hotel Election of Officers". The New York Times. March 31, 1900. p. 16. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 96047787.

- ^ "The Woman's Hotel; Subscriptions Now Reach $350,000 – Stock to be Offered to the Public". The New York Times. June 11, 1900. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 28, 2018. Retrieved September 16, 2023.

- ^ "Site for Woman's Hotel". New-York Tribune. September 7, 1900. p. 10. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 570849003.

- ^ "Land Bought for Woman's Hotel". New-York Tribune. January 27, 1901. p. 11. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 570921582. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ^ "Site for Woman's Hotel; Structure to be Erected on House of Industry Property. Agreed Price Reported to be $200,000 – The Twelve-Story Building Will House 500". The New York Times. January 26, 1901. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ^ "Plans for Woman's Hotel". New-York Tribune. February 9, 1901. p. 5. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 570904313.

- ^ "The Historical Society; Committee on Subscriptions Increased and an Appeal for the New Building". The New York Times. April 24, 1901. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ^ "New Woman's Hotel". New-York Tribune. April 24, 1901. p. 9. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 570993874.

- ^ "Woman's Hotel Plans". The New York Times. June 21, 1901. p. 12. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 96113647.

- ^ "New Woman's Hotel". New-York Tribune. June 21, 1901. p. 10. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 571021062.

- ^ "Contracts Awarded". The Real Estate Record: Real estate record and builders' guide. Vol. 68, no. 1742. August 3, 1901. p. 146. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 22, 2023 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "Of Interest to the Building Trades". The Real Estate Record: Real estate record and builders' guide. Vol. 68, no. 1761. December 14, 1901. p. 828. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 22, 2023 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "To Build a Big Hotel; Shanley Brothers Secure a Large Plot Near Long Acre Square". The New York Times. September 17, 1901. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ^ "Woman's Hotel Named". New-York Tribune. December 24, 1901. p. 5. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 571121298.

- ^ a b "New York: Manhattan New Woman's Hotel Under Way". New York Observer and Chronicle. Vol. 80, no. 1. January 2, 1902. p. 15. ProQuest 136271388.

- ^ "Daughter's Contract: Mrs. Davidge Will Decorate Part of New York Woman's Hotel". St. Louis Post – Dispatch. February 6, 1902. p. 1. ProQuest 577435498.

- ^ a b c Stephenson, Walter T. (October 1903). "Hotels and Hotel Life in New York". the Pall Mall Magazine. Vol. 31, no. 126. p. 260. ProQuest 6573113.

- ^ Cocks, Catherine (2001). Doing the Town: The Rise of Urban Tourism in the United States, 1850–1915. University of California Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-520-92649-3. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- ^ Bowdoin 1903, p. 1491.

- ^ a b c "No Pets in Woman's Hotel: New "Martha Washington," Exclusively Feminine, Bars Cats". The Sun. February 10, 1903. p. 10. ProQuest 536606838.

- ^ "Hotel Baby Was Just Smuggled In". The Evening World. January 16, 1904. p. 3. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ^ "No Place for Fair Plaintiffs: Hotel Martha Washington Bars Women Who Get Into the Courts". San Francisco Chronicle. September 10, 1906. p. 2. ProQuest 251357363.

- ^ a b "Woman's Hotel Is Opened". The Buffalo Review. February 25, 1903. p. 5. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ^ "Women Waiters on a Strike". New-York Tribune. May 16, 1903. p. 1. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 571395085.

- ^ "Hotel Martha Washington and Women Workers There". Star-Gazette. June 9, 1904. p. 6. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ^ "Miss Gould Lends Art Objects: Hotel Martha Washington is to Have Her Collection of Paintings and Statuary". New-York Tribune. April 18, 1903. p. 7. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 571241174.

- ^ "Tips Scarce in Women's Hotel: Failure of the Guests to Fee Waitresses Causes Walkout in New York Hostelry". San Francisco Chronicle. May 16, 1903. p. 5. ProQuest 365623261.

- ^ a b "Bellgirls and No Tips". The Sun. June 26, 1904. p. 7. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ^ "Deny There is Bar in Women's Hotel: Nothing Stronger Than Roman Punch Tolerated at the Martha Washington". San Francisco Chronicle. March 7, 1904. p. 5. ProQuest 573329163.

- ^ "Horrors! A Bar!: Chaste Corridors of Woman's Hotel May Have One Yet". New-York Tribune. February 17, 1904. p. 7. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 571513853.

- ^ "New York Women Want a Bar in Their Hotel". The Nashville American. February 21, 1904. p. 2. ProQuest 135320545.

- ^ "Girl a Success Running an Elevator". The Washington Post. March 6, 1904. p. B5. ISSN 0190-8286. ProQuest 144526284.

- ^ Green, Martin (June 24, 1904). "The Man Higher Up". The Evening World. p. 14. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ^ "More Martha Men Go: Women's Hotel Manager Thinks Waitresses Are Better". New-York Tribune. September 1, 1904. p. 1. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 571596480. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ^ "Women's Hotel Rates Up: Martha Washington Hereafter Will Be Run for Dividends". New-York Tribune. October 6, 1905. p. 5. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 571732596. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ^ a b c d "The Martha Washington Leased for Ten Years; Directors Hold a Lively Annual Meeting – Management Attacked". The New York Times. January 29, 1907. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ a b "Martha Washington Hotel: "for Women Only" Place in New York Not Satisfactory". The Nashville American. December 29, 1906. p. 3. ProQuest 940464876.

- ^ "To Lease Woman's Hotel: Trouble at Martha Washington—directors in Dispute". New-York Tribune. December 29, 1906. p. 3. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 940464876.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 2012, pp. 7–8.

- ^ a b c "Leased for Ten Years: A. W. Eager to Keep Martha Washington a Woman's Hotel". New-York Tribune. January 29, 1907. p. 4. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 571776526. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ^ "Hotel Man Dies; Had No Physician; Treated by Christian Science Healer for Ptomaine Poisoning – Ruptured Spleen Killed Him". The New York Times. August 12, 1911. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ^ a b "Hotel Changes Hands". The New York Times. March 2, 1920. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ^ a b "$800,000 Offered for Hotel Martha Washington". New-York Tribune. January 16, 1920. p. 19. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 576196401.

- ^ "Hotel Martha Washington Deal Is Consumated". New-York Tribune. January 28, 1920. p. 21. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 576174496.

- ^ a b "Martha Washington Sold; $1,000,000 Is Given for East Side Women's Hotel". The New York Times. January 28, 1920. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ^ "Well Scattered Budget of Sales". New York Herald. March 2, 1920. p. 17. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ^ "Brother Gets Bulk of Manger Estate; Hotel Owner Left Annuities to Other Relatives—Jackson Bequests Varied. Estate of Fannie A. Jackson". The New York Times. September 12, 1928. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ^ "William Manger Leaves Estate, To His Brother: Hotel Owner Bequeathed $5,000 Yearly to Seven of Kin; $10,000 to Sister". New York Herald Tribune. September 12, 1928. p. 23. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1113491711.

- ^ "Manger Estate Is Appraised at $4,487,801 Net: Hotel Operator's Brother Is Principal Legatee, Receiving $3,233,210 Residue Dodge Estate $3,849,387 J. Hartley Manners Holdings Are Estimated at $82,706". New York Herald Tribune. April 1, 1930. p. 21. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1113784584.

- ^ a b "Manger Interests Convey Martha Washington Hotel". New York Herald Tribune. February 16, 1948. p. 22. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1335171145.

- ^ a b "Hotel on 29th St. Bought and Resold: the Martha Washington Had Been Held by the Manger Chain for Over 25 Years". The New York Times. February 15, 1948. p. R1. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 108327233.

- ^ "Martha Washington Hotel Auctioned for $460,000: Boone Securities Corp. Takes Properly at Voluntary Sale". New York Herald Tribune. August 10, 1933. p. 30. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1221392430.

- ^ "Hotel Sold at Auction; Securities Corporation Bids $460,000 for the Martha Washington". The New York Times. August 10, 1933. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 16, 2023.

- ^ a b "Women's Hotel Gets License to Serve Wine, Recognizing a New Era in Drinking Habits". The New York Times. December 4, 1933. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ^ a b "Liquor Control Violators Facing Summary Arrest; Import Permits Recalled". New York Herald Tribune. December 4, 1933. p. 1. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1125469234.

- ^ "Celebrations in Clubs, Hotels and Restaurants to Mark Fulfillment of Hopes Long Held: Closing of 'Speaks' Left Up to Police Supply To Be Ample at First, With Time of Delivery Only Question in Return of Legal Liquor". New York Herald Tribune. December 5, 1933. p. 1. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1222053970.

- ^ "Julius Manger, 69, Hotel Owner, Dies; An Operator of Hostelry Chain in Four Cities Succumbs in Washington". The New York Times. March 29, 1937. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ^ Cox, Claire (March 28, 1949). "Want to Go Crazy? Run Hotel for Girls". The Austin Statesman. p. 2. ProQuest 1563555458.

- ^ "Buys Control of Hotel; Sillins Group Gets the Martha Washington on 29th Street". The New York Times. September 14, 1950. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 16, 2023.

- ^ "Martha Washington Hotel Bought by Sillins Chain". New York Herald Tribune. September 15, 1950. p. 24. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1327392847.

- ^ "Transfers and Financing". New York Herald Tribune. November 25, 1953. p. 26. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1322363457.

- ^ Hoffecker, Felicity (January 6, 1961). "Bay Ridge Business Beat". Bay Ridge Home Reporter. p. 8. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 21, 2023.

- ^ "New Club to Bow". Daily News. April 19, 1967. p. 87. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 21, 2023.

- ^ Altshul, Jack (May 19, 1972). "It Was All Greek to Me—Until". Newsday. p. 63. ISSN 2574-5298. ProQuest 917493521.

- ^ a b c Rosenblatt, Gary (October 10, 1972). "Those Traditional Hotels for Women: Standing Still in Time". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 21, 2023.

- ^ a b Sutton, Horace (June 20, 1982). "New York's Barbizon Hotel is Finally Going Coed". Chicago Tribune. p. 205. ISSN 1085-6706. Archived from the original on February 17, 2023. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- ^ Fosburgh, Lacey (January 15, 1971). "City Rights Unit Ponders Sex Law". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 16, 2023. Retrieved February 16, 2023.

- ^ Charlton, Linda (January 20, 1972). "City Widens Ban on Bias Over Sex". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 16, 2023. Retrieved February 16, 2023.

- ^ a b "N.Y. panel rules out ladies' day, women's hotels". The Christian Science Monitor. January 24, 1972. p. 18. ProQuest 511273109.

- ^ "Malcolm Takes Correction Post". The Herald Statesman. January 20, 1972. p. 5. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 21, 2023.

- ^ "Wants to Keep 1-Sex Hotels". Daily News. February 21, 1972. p. 168. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 21, 2023.

- ^ Sullivan, Karen (July 13, 1973). "Women Have Changed, But Women's Hotels Remain Quite Proper: Result: Occupancy Rates Fall; But 'Right Kind of Girl Still Stays Here;' Room for Men? Women Have Changed, But Women's Hotels Remain Quite Proper". Wall Street Journal. p. 1. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 133801946.

- ^ Schiro, Anne-Marie (November 7, 1982). "For Women: Safe Places to Stay". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 13, 2016. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ "New Danceteria to Serve the Hip". Daily News. May 3, 1991. p. 194. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ Rifkin, Jesse (2023). This Must Be the Place: Music, Community and Vanished Spaces in New York City. Hanover Square Press. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-3697-3299-6. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ Katz, Mike; Kott, Crispin (2018). Rock and Roll Explorer Guide to New York City. Globe Pequot. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-4930-3704-9. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ Krauss, Clifford (October 11, 1994). "Eight Youths Are Wounded In Shootings at Dance Club". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 26, 2015. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ Siegal, Nina (November 22, 1998). "Checkout Time?; As S.R.O. Owners Make Way for Tourists, Long-Term Tenants Say They're Left in the Lurch". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 8, 2023. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ Moritz, Owen (August 28, 2000). "Tax Deadbeats Snared in City Web of Shame". New York Daily News. p. 7. ISSN 2692-1251. ProQuest 305573909.

- ^ Lentz, Philip (February 7, 2000). "NY rats out tax delinquents with the click of a mouse". Crain's New York Business. Vol. 16, no. 6. p. 4. ProQuest 219152531.

- ^ a b c Oser, Alan S. (August 26, 1998). "Commercial Real Estate; Upgrading a Cluster of Older Hotels in Manhattan". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 7, 2021. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ McCarthy, Sheryl (December 7, 1998). "The City Grows Civilized in All Ways but Housing". Newsday. p. A32. ISSN 2574-5298. ProQuest 279181642.

- ^ Pedersen, Laura (August 6, 2000). "Home Sweet Hotel". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 14, 2022. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ Lambert, Bruce (June 29, 2000). "Metro Briefing". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 27, 2015. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ Holusha, John (April 16, 2000). "Commercial Property; In Manhattan, a Scattering of New Hotels". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 15, 2022. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ a b Adams, Marilyn (October 31, 2000). "Big Apple hotel rates don't have to bite Savvy business travelers can find rooms for $200 or less". USA Today. p. B5. ProQuest 408870453.

- ^ "Postings: Renovated Hotel at 77th and Broadway Gets 4 More Floors; Adding 23 Rooms at the Top". The New York Times. July 16, 2000. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 27, 2015. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ Morris, Jerry (October 3, 1999). "Opening of Renovated Radio City Highlights Fall". Sun Sentinel. p. 7J. ProQuest 388093239.

- ^ a b Barbarino, Al (June 29, 2012). "Real Estate Weekly". Real Estate Weekly. Archived from the original on August 8, 2022. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ Hughes, C. J. (August 22, 2007). "Counting on a Hotel to Make a Neighborhood Hot". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 24, 2023. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ a b Vilensky, Mike (December 5, 2011). "The Hotel Where Every Night Is Ladies' Night". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ "Fitch Upgrades 4 Classes of CGCMT 2007-FL3". Fitch Ratings. June 1, 2012. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ a b "King & Grove adds Hotel Lola to portfolio". The Real Deal. June 5, 2012. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 16, 2023.

- ^ Jones, David (August 28, 2013). "Chetrits, King & Grove break up hotel partnership". The Real Deal. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 16, 2023.

- ^ Feitelberg, Rosemary (May 23, 2014). "Ed Scheetz Launches Chelsea Hotels". WWD. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved September 16, 2023.

- ^ Morabito, Greg (October 8, 2013). "Danny Meyer's Group to Open King & Grove Restaurant". Eater NY. Archived from the original on May 30, 2023. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ Teclemariam, Tammie; Sytsma, Alan; Quittner, Ella; Pariso, Dominique (October 8, 2013). "Danny Meyer Opening a Restaurant Inside King & Grove's Manhattan Hotel". Grub Street. Archived from the original on October 4, 2022. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ Kludt, Amanda (September 29, 2014). "A Timeline: Everything You Need to Know About Danny Meyer's Marta". Eater NY. Archived from the original on June 7, 2023. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ Teclemariam, Tammie; Sytsma, Alan; Quittner, Ella; Pariso, Dominique (May 13, 2014). "Danny Meyer Will Open Wood-Fired Pizzeria Inside King & Grove's Manhattan Hotel". Grub Street. Archived from the original on August 12, 2022. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ Jones, David (May 22, 2014). "Ed Scheetz renaming King & Grove the Chelsea Hotels". The Real Deal. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 16, 2023.

- ^ Clarke, Katherine (May 22, 2014). "Owner of Hotel Chelsea will rebrand his other inns to capitalize on a world-renowned name". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 16, 2023.

- ^ a b Laterman, Kaya (October 3, 2014). "Tony Hotels and Restaurants Spice Up NoMad". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on October 27, 2014. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ Sutton, Ryan (October 28, 2014). "Marta, Danny Meyer's First and Only Pizzeria, Delivers the Goods". Eater NY. Archived from the original on June 10, 2023. Retrieved September 16, 2023.

- ^ Wells, Pete (December 2, 2014). "Restaurant Review: Danny Meyer's Marta in NoMad". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 26, 2022. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ Geiger, Daniel (March 30, 2015). "Chelsea Hotels looking to sell". Crain's New York Business. Vol. 31, no. 13. p. 40. ProQuest 1668323058.

- ^ "CIM Buys Martha Washington Hotel in N.Y." Los Angeles Business Journal. November 24, 2015. Archived from the original on April 9, 2016. Retrieved April 15, 2016.

- ^ Stulberg, Ariel (November 24, 2015). "CIM paid $158M for Martha Washington Hotel". The Real Deal. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 16, 2023.

- ^ "CIM buys Martha Washington Hotel". The Real Deal. November 13, 2015. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 16, 2023.

- ^ Walsh, Nora (June 24, 2016). "7 New Hotels in New York City". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 26, 2023. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ a b "The Redbury New York Opens". LODGING Magazine. October 28, 2016. Archived from the original on January 18, 2022. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ Sell, George (October 30, 2016). "sbe opens The Redbury, its first NYC hotel". Boutique Hotel News. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ Jelski, Christina (August 26, 2019). "Redbury New York undergoing renovations". Travel Weekly. Archived from the original on May 30, 2023. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ Krueger, Alyson (April 7, 2020). "How a Luxury Hotel on Billionaires' Row Became a Dorm for Hospital Workers". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 7, 2022. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ Sisson, Patrick (October 19, 2020). "Serious Reservations: Midtown South's Hotels Confront COVID". Commercial Observer. Archived from the original on December 26, 2022. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ Kvetenadze, Téa (August 25, 2023). "Manhattan's historic Gramercy Park Hotel has new operator, sets reopening date of 2025; Babe Ruth and David Bowie among famous guests". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ Romano, Aaron; Dreizen, Collin (October 19, 2022). "Maialino Reopens at New Manhattan Location; Group Behind Nice Matin Debuts Monterey". Wine Spectator. Archived from the original on August 24, 2023. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ Fortney, Luke (August 3, 2023). "A Manhattan Hotel With Two Danny Meyer Restaurants Will House Asylum Seekers". Eater NY. Archived from the original on August 23, 2023. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ a b Newman, Andy; Schweber, Nate (August 10, 2023). "New York City Said It Had No More Beds for Migrants. What Changed?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 8, 2023. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ Marroquin, Mario (August 18, 2023). "Everything to know about how the migrant crisis is changing the city's real estate". Crain's New York Business. Archived from the original on September 20, 2023. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ Moore, Jessica (August 9, 2023). "Influx of children of asylum seekers means "everything changes," Mayor Adams says". CBS New York. Archived from the original on August 16, 2023. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ Stevens, Ellie (August 17, 2023). "Danny Meyer closes two restaurants in a New York hotel that was converted into a migrant shelter". CNN. Archived from the original on August 24, 2023. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ Bramer, James Van (August 16, 2023). "Danny Meyer Shuts Midtown Hotel Restaurants". The Real Deal. Archived from the original on August 16, 2023. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ Sirtori-Cortina, Daniela (August 14, 2023). "Two Danny Meyer Restaurants Will Close With Their NYC Homes Becoming Migrant Shelters". Bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on August 16, 2023. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ a b Kozolchyk, Abbie (March 9, 2023). "6 Hotels in the US That Influenced Women's History". Condé Nast Traveler. Archived from the original on April 5, 2023. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ "Duchess Coming to Woman's Hotel; Rooms Being Prepared for Duchess of Marlborough in Martha Washington". The New York Times. March 6, 1907. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ^ "Veronica Lake: A Dupe in Bogus Stock Sale". New York Herald Tribune. December 7, 1962. p. 5. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1326010537.

- ^ Tangney, William E. (March 22, 1962). "Glamor Girl Veronica Working for Meals". The Austin Statesman. p. A11. ProQuest 1527596053.

- ^ "What Ever Happened to Veronica Lake". Newsday. March 23, 1962. p. 2C. ISSN 2574-5298. ProQuest 899019596.

- ^ "It's Now Life as a Waitress for Ex Star Veronica Lake". The Buffalo News. March 22, 1962. p. 6. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 21, 2023.

- ^ Klemesrud, Judy (March 10, 1971). "For Veronica Lake, the Past Is Something to Write About". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 16, 2023. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ "Fran Lebowitz with Phong Bui". The Brooklyn Rail. August 19, 2024.

- ^ "Business Women Are Organized; Two Young Men Accomplish the Feat at Hotel Martha Washington Meeting". The New York Times. September 29, 1908. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ^ "Women in the Campaign; Republican Headquarters at Martha Washington – Democratic at Waldorf". The New York Times. September 26, 1908. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ^ "No More Sample Pillows". New York Herald Tribune. June 17, 1945. p. 24. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1325073169.

- ^ "Hotel Exclusively for Women: New York Hostelry Is More Like a Club". The Christian Science Monitor. April 30, 1910. p. D5. ProQuest 508100856.

- ^ Newcomer, Eric P. (June 13, 2012). "3 Firehouses Among 6 Buildings Now Designated City Landmarks". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 13, 2012. Retrieved June 13, 2012.

- ^ "Hotel History – The Redbury New York". Historic Hotels of America. Archived from the original on December 14, 2022. Retrieved December 14, 2022.

- ^ "The 2023 Top 25 Historic Hotels of America Where Women Made History". Bloomberg.com. March 27, 2023. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

Sources

- Bowdoin, William Goodrich (June 25, 1903). "The Hotel Martha Washington: an Interesting Experiment in Inn Keeping". The Independent ... Devoted to the Consideration of Politics, Social and Economic Tendencies, History, Literature, and the Arts. Vol. 55, no. 2847. pp. 1491–1492. ProQuest 90538762.

- Martha Washington Hotel (PDF) (Report). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 19, 2012.