Malha

Malha المالحة

מלחה | |

|---|---|

| |

| Etymology: The salt-pan[1] | |

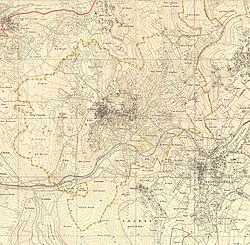

Village boundaries of Maliha in the Mandatory Palestine period | |

| Palestine grid | 167/129 |

| Geopolitical entity | Mandatory Palestine |

| Subdistrict | Jerusalem |

| Date of depopulation | 21 April 1948, 15 July 1948[2] |

| Area | |

• Total | 13,449 dunams (13.449 km2 or 5.193 sq mi) |

| Population (1948[5]) | |

• Total | 1,940[4][3] |

| Cause(s) of depopulation | Influence of nearby town's fall |

| Secondary cause | Military assault by Yishuv forces |

Malha is a neighborhood in southwest Jerusalem, between Pat, Ramat Denya and Kiryat Hayovel in the Valley of Rephaim. Before 1948, Malha was an Arab village known as al-Maliha (Arabic: المالحة).

Excavations in Malha revealed structures from the Bronze Age. In biblical times, it was the site of Manahat, located in the territory of Judah. In the fifth century, it was inhabited by Christian Georgians. During Ottoman times, it was a Muslim town with locals originating from Transjordan and Egypt. In the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, the village's inhabitants fled, and Jewish refugees from Middle Eastern countries settled there, with some of the land already purchased by Sephardic Jews before the war.

Malha is now an upscale neighborhood featuring the Malha Shopping Mall, Teddy Stadium, and the Jerusalem Technology Park.

History

Antiquity

Excavations in Malha revealed Intermediate Bronze Age domestic structures.[6] A dig in the Rephaim Valley carried out by the Israel Antiquities Authority in the region of the Malha Shopping Mall and Biblical Zoo uncovered a village dating back to the Middle Bronze Age II B (1,700 – 1,800 BCE). Beneath this, remains of an earlier village were found from the Early Bronze Age IV (2,200 – 2,100 BCE).[7]

According to the archaeologists who excavated there in 1987–1990, Malha is believed to be the site of Manahat, a Canaanite town on the northern border of the Tribe of Judah (Joshua 15:58–59[clarification needed]).[8] Remains of the village have been preserved at the Biblical Zoo.[8]

Byzantine- to Late Ottoman-period Georgian presence

Malha was a Georgian village in the fifth century, in the time of King Vakhtang I Gorgasali, who was canonized by the Georgian Orthodox Church.[9] There was a connection to the nearby Georgian Monastery of the Cross and other Georgian religious establishments around Jerusalem, with travellers noticing distinct habits among Malha's residents for centuries.[9] Eventually they adopted Islam and integrated into the surrounding Arab society.[9] By the 18th and 19th centuries, little more than the faint traces of a church, the few remaining locals naming themselves "Gurjs", Georgians, and their right of working the lands of the Monastery of the Cross remained as witness of the Georgian past.[10]

Ottoman period

In the 1596 tax records al-Maliha, (named Maliha as-Suqra), was part of the Ottoman Empire, nahiya (subdistrict) of Jerusalem under the Liwa of Jerusalem. It had a population of 52 Muslim households, an estimated 286 persons. The villagers paid a fixed tax rate of 33,3% on wheat, barley, and olive and fruit trees, goats and beehives; a total of 8,700 akçe. 1/3 of the revenue went to a waqf.[13]

In 1838 it was noted by Edward Robinson as el Malihah, a Muslim village, part of the Beni Hasan district.[14][15]

An Ottoman village list from about 1870 showed Malha with a population of 340, in 75 houses, though the population count included men, only.[16][17]

During a visit in the 1870s, Clermont-Ganneau recorded a local tradition stating that the residents could be categorized into two distinct origins: one group hailing from Transjordan and another from Egypt. Ganneau pointed out the locals' "peculiar" way of speaking, where their "a" sounds were long and similar to "o." He documented several findings including a broken inscription, rock-cut tombs, and a box of bones, shown to him by the locals. He also mentioned Ain Yalo, a nearby spring highly celebrated by the locals.[18]

In 1883, the PEF's Survey of Western Palestine (SWP) described the village as being of moderate size, standing high on a flat ridge. To the south was Ayn Yalu.[19]

In 1896 the population of Malha was estimated to be about 600 persons.[20]

British Mandate period

In the 1922 census of Palestine conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Malhah had a population 1,038, all Muslims,[21] increasing in the 1931 census to 1,410; 1,402 Muslims and 8 Christians, in a total of 299 houses.[22] Georgian researcher, B.V. Khurtsilava, connected the steep population rise between 1868 (c. 200), to 1896 (some 600) and the 1920s-30s (c. 100–1400) with a strong influx of people of various ethnic backgrounds.[23]

In the 1945 statistics the population of Malha was 1,940; 1,930 Muslims and 10 Christians,[4] and the total land area was 6,828 dunams, according to an official land and population survey.[3] Of the land, a total of 2,618 dunams were plantations and irrigable land and 1,259 were for cereals,[24] while a total of 328 dunams were built-up (urban) land.[25]

1948 war

In the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, the village of al-Maliha, with a population of 2,250, was occupied as part of the battle for south Jerusalem.[26] In the early part of the war, Al-Maliha, along with al-Qastal, Sur Baher and Deir Yassin, signed non-aggression pacts with the Haganah.[27] On April 12, 1948, in the wake of the Deir Yassin Massacre, villagers from al Maliha, Qaluniya and Beit Iksa began to flee in panic.[28] The Irgun attacked Malha in early morning hours of July 14, 1948. Several hours later, the Palestinian Arabs launched a counter-attack and seized one of the fortified positions. When Irgun reinforcements arrived, the Palestinian militia retreated and Malha was in Jewish control, but 17 Irgun fighters were killed and many wounded.[29] The remaining Arab inhabitants either fled or were expelled to Bethlehem, which remained under Jordanian control. The depopulated homes were occupied by Jewish refugees from Middle Eastern countries, mainly Iraq. Some of the land in Malha had been purchased before the establishment of the state by the Valero family, a family of Sephardi Jews that owned large amounts of property in Jerusalem and environs.[30]

Israel

The first Palestinian fedayeen raid in Israel took place in November 1951 in Malha when a woman, Leah Festinger, was killed by infiltrators from Shuafat, at the time part of Jordan.[31]

Recent development

Under the aegis of the Jerusalem Municipality, the neighborhood was modernised and a large housing development was established on the nearby hill and its eastern slopes. At the bottom of the hill are the Malha Shopping Mall, Teddy Stadium, Pais Arena Jerusalem, Jerusalem Biblical Zoo and the Jerusalem Malha Railway Station. Malha is now considered an upscale neighborhood. Schools include a vocational high school (ORT) and an elementary school, the Shalom School. The Jerusalem Technology Park houses many companies, including some high-tech start-ups as well as international media offices.[32] In 2019, plans were approved for the construction of 30-floor towers in the technology park.[33] A line of the Jerusalem Light Rail is being built from Jerusalem's Central Bus Station to the Malha sports complex.[34]

See also

References

- ^ Palmer, 1881, p. 322

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. xx, village #361. Also gives the cause for depopulation

- ^ a b c Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 57

- ^ a b Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 25

- ^ Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics Archived 2012-02-12 at the Wayback Machine Depopulated Jerusalem Localities of the year 1948 by Selected Variables

- ^ An Intermediate Bronze Age Farmhouse at Newe Shalom

- ^ Refaim Valley: The Palestinian villages of Al Wallaja and Battir, Archaeological View

- ^ a b Nahal Refa'im - Canaanite Bronze Age villages near Jerusalem. History: ARCHEOLOGICAL SITES NO. 6. Posted 20.11.2000. Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Accessed 25 September 2023.

- ^ a b c Georgian ambassador's move to Jerusalem highlights history, Jerusalem Post. Re-accessed 25 September 2023.

- ^ Khurtsilava, Besik V. (2017). Sentries of "Jvari": On the traces of Gurjs from Malha. Ch. 2. First Data on forgotten tribesmen, pp. 23-24 (English translation). In "Georgia and Holy Land", Tbilisi. Accessed 25 September 2023.

- ^ Arab MK welcomes cancellation of Argentina soccer game, Jun 6, 2018; Arutz Sheva, ""I congratulate the Argentine team on its decision to cancel the game at Al-Maliha Stadium," tweeted Zahalka, referencing the name the Arabs use to call the Teddy Stadium, where the game was to have been played."

- ^ Beitar cancels Barcelona match after demand to not have game in Jerusalem, July 15, 2021; Jerusalem Post: "Palestinian Football Association president Jibril Rajoub received a letter from Laport about the match planned in Jerusalem on August 4 "in a stadium built on the ruins of the Palestinian village of al-Malha, whose residents were forcibly expelled and displaced in refugee camps," Wafa reported."

- ^ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 118. Quoted in Khalidi, 1992, p. 304

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, Appendix 2, p. 123

- ^ Robinson & Smith, 1841, vol 2, p. 156

- ^ Socin, 1879, p. 157, also noted it to be in the Beni Hasan district

- ^ Hartmann, 1883, p. 122, also noted 75 houses

- ^ "The Jerusalem Researches". Palestine Exploration Quarterly. 6 (3): 160–161. 1874. doi:10.1179/peq.1874.016. ISSN 0031-0328.

- ^ Conder and Kitchener, 1883, SWP III, p. 21. Quoted in Khalidi, 1992, p.304

- ^ Schick, 1896, p. 125

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table VII, Sub-district of Jerusalem, p. 14

- ^ Mills, 1932, p. 41

- ^ Khurtsilava, Besik V. (2017). Ch. 4. Pages of sad history of Malha residents, pp. 29-30.

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 103

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 153

- ^ Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics Archived 2012-02-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Morris, 2004, pp. 75, 91

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 239

- ^ Morris, Benny (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. pp. 239, 435–436. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- ^ Sephardi entrepreneurs in Jerusalem: The Valero family, 1800-1948, Joseph B. Glass, Ruth Kark

- ^ Ynet Encyclopedia

- ^ Malha Technological Centre Archived 2008-12-01 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Two 30-floor towers approved for Jerusalem's Malha, Globes

- ^ Jerusalem light rail to expand to 5 lines, 27km of tracks

Bibliography

- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1883). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 3. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945.

- Guérin, V. (1868). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 1: Judee, pt. 1. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Guérin, V. (1869). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 1: Judee, pt. 2. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Hartmann, M. (1883). "Die Ortschaftenliste des Liwa Jerusalem in dem türkischen Staatskalender für Syrien auf das Jahr 1288 der Flucht (1871)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 6: 102–149.

- Hütteroth, W.-D.; Abdulfattah, K. (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Khalidi, W. (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 2. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Rogers, Mary Eliza (1862). Domestic Life in Palestine. Bell & Daldy.

- Schick, C. (1896). "Zur Einwohnerzahl des Bezirks Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 19: 120–127.

- Socin, A. (1879). "Alphabetisches Verzeichniss von Ortschaften des Paschalik Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 2: 135–163.

- Tobler, T. (1854). Dr. Titus Toblers zwei Bucher Topographie von Jerusalem und seinen Umgebungen (in German). Vol. 2. Berlin: G. Reimer. (pp. 760 ff)

- Khurtsilava, B. (2022). "Gurjis" from Palestine. pp. 17–39 https://www.academia.edu/83562888/BESIK_KHURTSILAVA_GURJIS_FROM_PALESTINE_TBILISI_2022_in_English_

External links

- Photos of the neighborhood

- Al-Maliha village at palestineremembered.com

- al-Maliha, Zochrot

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 17: IAA, Wikimedia commons