Magnetic resonance angiography

| Magnetic resonance angiography | |

|---|---|

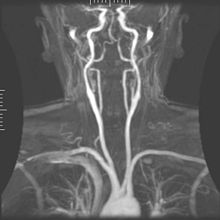

Time-of-flight MRA at the level of the Circle of Willis. | |

| MeSH | D018810 |

| OPS-301 code | 3-808, 3-828 |

| MedlinePlus | 007269 |

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is a group of techniques based on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to image blood vessels. Magnetic resonance angiography is used to generate images of arteries (and less commonly veins) in order to evaluate them for stenosis (abnormal narrowing), occlusions, aneurysms (vessel wall dilatations, at risk of rupture) or other abnormalities. MRA is often used to evaluate the arteries of the neck and brain, the thoracic and abdominal aorta, the renal arteries, and the legs (the latter exam is often referred to as a "run-off").

Acquisition

A variety of techniques can be used to generate the pictures of blood vessels, both arteries and veins, based on flow effects or on contrast (inherent or pharmacologically generated). The most frequently applied MRA methods involve the use intravenous contrast agents, particularly those containing gadolinium to shorten the T1 of blood to about 250 ms, shorter than the T1 of all other tissues (except fat). Short-TR sequences produce bright images of the blood. However, many other techniques for performing MRA exist, and can be classified into two general groups: 'flow-dependent' methods and 'flow-independent' methods.[citation needed]

Flow-dependent angiography

One group of methods for MRA is based on blood flow. Those methods are referred to as flow dependent MRA. They take advantage of the fact that the blood within vessels is flowing to distinguish the vessels from other static tissue. That way, images of the vasculature can be produced. Flow dependent MRA can be divided into different categories: There is phase-contrast MRA (PC-MRA) which utilizes phase differences to distinguish blood from static tissue and time-of-flight MRA (TOF MRA) which exploits that moving spins of the blood experience fewer excitation pulses than static tissue, e.g. when imaging a thin slice.[citation needed]

Time-of-flight (TOF) or inflow angiography, uses a short echo time and flow compensation to make flowing blood much brighter than stationary tissue. As flowing blood enters the area being imaged it has seen a limited number of excitation pulses so it is not saturated, this gives it a much higher signal than the saturated stationary tissue. As this method is dependent on flowing blood, areas with slow flow (such as large aneurysms) or flow that is in plane of the image may not be well visualized. This is most commonly used in the head and neck and gives detailed high-resolution images. It is also the most common technique used for routine angiographic evaluation of the intracranial circulation in patients with ischemic stroke.[1]

Phase-contrast MRA

Phase-contrast (PC-MRA) can be used to encode the velocity of moving blood in the magnetic resonance signal's phase.[3] The most common method used to encode velocity is the application of a bipolar gradient between the excitation pulse and the readout. A bipolar gradient is formed by two symmetric lobes of equal area. It is created by turning on the magnetic field gradient for some time, and then switching the magnetic field gradient to the opposite direction for the same amount of time.[4] By definition, the total area (0th moment) of a bipolar gradient, , is null:

- (1)

The bipolar gradient can be applied along any axis or combination of axes depending on the direction along which flow is to be measured (e.g. x).[5] , the phase accrued during the application of the gradient, is 0 for stationary spins: their phase is unaffected by the application of the bipolar gradient. For spins moving with a constant velocity, , along the direction of the applied bipolar gradient:

- (2)

The accrued phase is proportional to both and the 1st moment of the bipolar gradient, , thus providing a means to estimate . is the Larmor frequency of the imaged spins. To measure , of the MRI signal is manipulated by bipolar gradients (varying magnetic fields) that are preset to a maximum expected flow velocity. An image acquisition that is reverse of the bipolar gradient is then acquired and the difference of the two images is calculated. Static tissues such as muscle or bone will subtract out, however moving tissues such as blood will acquire a different phase since it moves constantly through the gradient, thus also giving its speed of the flow. Since phase-contrast can only acquire flow in one direction at a time, 3 separate image acquisitions in all three directions must be computed to give the complete image of flow. Despite the slowness of this method, the strength of the technique is that in addition to imaging flowing blood, quantitative measurements of blood flow can be obtained.

Flow-independent angiography

Whereas most of techniques in MRA rely on contrast agents or flow into blood to generate contrast (Contrast Enhanced techniques), there are also non-contrast enhanced flow-independent methods. These methods, as the name suggests, do not rely on flow, but are instead based on the differences of T1, T2 and chemical shift of the different tissues of the voxel. One of the main advantages of this kind of techniques is that we may image the regions of slow flow often found in patients with vascular diseases more easily. Moreover, non-contrast enhanced methods do not require the administration of additional contrast agent, which have been recently linked to nephrogenic systemic fibrosis in patients with chronic kidney disease and kidney failure.

Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography uses injection of MRI contrast agents and is currently the most common method of performing MRA.[2][6] The contrast medium is injected into a vein, and images are acquired both pre-contrast and during the first pass of the agent through the arteries. By subtraction of these two acquisitions in post-processing, an image is obtained which in principle only shows blood vessels, and not the surrounding tissue. Provided that the timing is correct, this may result in images of very high quality. An alternative is to use a contrast agent that does not, as most agents, leave the vascular system within a few minutes, but remains in the circulation up to an hour (a "blood-pool agent"). Since longer time is available for image acquisition, higher resolution imaging is possible. A problem, however, is the fact that both arteries and veins are enhanced at the same time if higher resolution images are required.

Subtractionless contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography: recent developments in MRA technology have made it possible to create high quality contrast-enhanced MRA images without subtraction of a non-contrast enhanced mask image. This approach has been shown to improve diagnostic quality,[7] because it prevents motion subtraction artifacts as well as an increase of image background noise, both direct results of the image subtraction. An important condition for this approach is to have excellent body fat suppression over large image areas, which is possible by using mDIXON acquisition methods. Traditional MRA suppresses signals originating from body fat during the actual image acquisition, which is a method that is sensitive to small deviations in the magnetic and electromagnetic fields and as a result may show insufficient fat suppression in some areas. mDIXON methods can distinguish and accurately separate image signals created by fat or water. By using the 'water images' for MRA scans, virtually no body fat is seen so that no subtraction masks are needed for high quality MR venograms.

Non-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography: Since the injection of contrast agents may be dangerous for patients with poor kidney function, others techniques have been developed, which do not require any injection. These methods are based on the differences of T1, T2 and chemical shift of the different tissues of the voxel. A notable non-enhanced method for flow-independent angiography is balanced steady-state free precession (bSSFP) imaging which naturally produces high signal from arteries and veins.

2D and 3D acquisitions

For the acquisition of the images two different approaches exist. In general, 2D and 3D images can be acquired. If 3D data is acquired, cross sections at arbitrary view angles can be calculated. Three-dimensional data can also be generated by combining 2D data from different slices, but this approach results in lower quality images at view angles different from the original data acquisition. Furthermore, the 3D data can not only be used to create cross sectional images, but also projections can be calculated from the data. Three-dimensional data acquisition might also be helpful when dealing with complex vessel geometries where blood is flowing in all spatial directions (unfortunately, this case also requires three different flow encodings, one in each spatial direction). Both PC-MRA and TOF-MRA have advantages and disadvantages. PC-MRA has fewer difficulties with slow flow than TOF-MRA and also allows quantitative measurements of flow. PC-MRA shows low sensitivity when imaging pulsating and non-uniform flow. In general, slow blood flow is a major challenge in flow dependent MRA. It causes the differences between the blood signal and the static tissue signal to be small. This either applies to PC-MRA where the phase difference between blood and static tissue is reduced compared to faster flow and to TOF-MRA where the transverse blood magnetization and thus the blood signal are reduced. Contrast agents may be used to increase blood signal – this is especially important for very small vessels and vessels with very small flow velocities that normally show accordingly weak signal. Unfortunately, the use of gadolinium-based contrast media can be dangerous if patients suffer from poor renal function. To avoid these complications as well as eliminate the costs of contrast media, non-enhanced methods have been researched recently.

Non-enhanced techniques in development

Flow-independent NEMRA methods are not based on flow, but exploit differences in T1, T2 and chemical shift to distinguish blood from static tissue.

Gated subtraction fast spin-echo: An imaging technique that subtracts two fast spin echo sequences acquired at systole and diastole. Arteriography is achieved by subtracting the systolic data, where the arteries appear dark, from the diastolic data set, where the arteries appear bright. Requires the use of electrocardiographic gating. Trade names for this technique include Fresh Blood Imaging (Toshiba), TRANCE (Philips), native SPACE (Siemens) and DeltaFlow (GE).

4D dynamic MR angiography (4D-MRA): The first images, before enhancement, serve as a subtraction mask to extract the vascular tree in the succeeding images. Allows the operator to divide arterial and venous phases of a blood-groove with visualisation of its dynamics. Much less time has been spent researching this method so far in comparison with other methods of MRA.

BOLD venography or susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI): This method exploits the susceptibility differences between tissues and uses the phase image to detect these differences. The magnitude and phase data are combined (digitally, by an image-processing program) to produce an enhanced contrast magnitude image which is exquisitely sensitive to venous blood, hemorrhage and iron storage. The imaging of venous blood with SWI is a blood-oxygen-level dependent (BOLD) technique which is why it was (and is sometimes still) referred to as BOLD venography. Due to its sensitivity to venous blood SWI is commonly used in traumatic brain injuries (TBI) and for high resolution brain venographies.

Similar procedures to flow effect based MRA can be used to image veins. For instance, Magnetic resonance venography (MRV) is achieved by exciting a plane inferiorly while signal is gathered in the plane immediately superior to the excitation plane, and thus imaging the venous blood which has recently moved from the excited plane. Differences in tissue signals, can also be used for MRA. This method is based on the different signal properties of blood compared to other tissues in the body, independent of MR flow effects. This is most successfully done with balanced pulse sequences such as TrueFISP or bTFE. BOLD can also be used in stroke imaging in order to assess the viability of tissue survival.

Artifacts

MRA techniques in general are sensitive to turbulent flow, which causes a variety of different magnetized proton spins to lose phase coherence (intra-voxel dephasing phenomenon), resulting in a loss of signal. This phenomenon may result in the overestimation of arterial stenosis. Other artifacts observed in MRA include:

- Phase-contrast MRA: Phase wrapping caused by the underestimation of maximum blood velocity in the image. The fast-moving blood about maximum set velocity for phase-contrast MRA gets aliased and the signal wraps from pi to -pi instead, making flow information unreliable. This can be avoided by using velocity encoding (VENC) values above the maximum measured velocity. It can also be corrected with the so-called phase-unwrapping.

- Maxwell terms: caused by the switching of the gradients field in the main field B0. This causes the over magnetic field to be distort and give inaccurate phase information for the flow.

- Acceleration: accelerating blood flow is not properly encoded by phase-contrast technique, which can lead to errors in quantifying blood flow.

- Time-of-flight MRA:

- Saturation artifact due to laminar flow: In many vessels, blood flow is slower near the vessel walls than near the center of the vessel. This causes blood near the vessel walls to become saturated and can reduce the apparent caliber of the vessel.

- Venetian blind artifact: Because the technique acquires images in slabs (as in Multiple overlapping thin-slab acquisition, MOTSA), a non-uniform flip angle across the slab can appear as horizontal stripe in the composed images.[8]

Visualization

Occasionally, MRA directly produces (thick) slices that contain the entire vessel of interest. More commonly, however, the acquisition results in a stack of slices representing a 3D volume in the body. To display this 3D dataset on a 2D device such as a computer monitor, some rendering method has to be used. The most common method is maximum intensity projection (MIP), where the computer simulates rays through the volume and selects the highest value for display on the screen. The resulting images resemble conventional catheter angiography images. If several such projections are combined into a cine loop or QuickTime VR object, the depth impression is improved, and the observer can get a good perception of 3D structure. An alternative to MIP is direct volume rendering where the MR signal is translated to properties like brightness, opacity and color and then used in an optical model.

Clinical use

MRA has been successful in studying many arteries in the body, including cerebral and other vessels in the head and neck, the aorta and its major branches in the thorax and abdomen, the renal arteries, and the arteries in the lower limbs. For the coronary arteries, however, MRA has been less successful than CT angiography or invasive catheter angiography. Most often, the underlying disease is atherosclerosis, but medical conditions like aneurysms or abnormal vascular anatomy can also be diagnosed.

An advantage of MRA compared to invasive catheter angiography is the non-invasive character of the examination (no catheters have to be introduced in the body). Another advantage, compared to CT angiography and catheter angiography, is that the patient is not exposed to any ionizing radiation. Also, contrast media used for MRI tend to be less toxic than those used for CT angiography and catheter angiography, with fewer people having any risk of allergy. Also far less is needed to be injected into the patient. The greatest drawbacks of the method are its comparatively high cost and its somewhat limited spatial resolution. The length of time the scans take can also be an issue, with CT being far quicker. It is also ruled out in patients for whom MRI exams may be unsafe (such as having a pacemaker or metal in the eyes or certain surgical clips).

MRA procedures for visualizing cranial circulation are no different from the positioning for a normal MRI brain. Immobilization within the head coil will be required. MRA is usually a part of the total MRI brain examination and adds approximately 10 minutes to the normal MRI protocol.

See also

References

- ^ Campeau; Huston (2012). "Vascular disorders—magnetic resonance angiography: Brain vessels". Neuroimaging Clin. N. Am. 22 (2): 207–33, x. doi:10.1016/j.nic.2012.02.006. PMID 22548929.

- ^ a b Hartung, Michael P; Grist, Thomas M; François, Christopher J (2011). "Magnetic resonance angiography: current status and future directions". Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. 13 (1): 19. doi:10.1186/1532-429X-13-19. ISSN 1532-429X. PMC 3060856. PMID 21388544. (CC-BY-2.0)

- ^ Moran, Paul R. (1985). "Verification and Evaluation of Internal Flow and Motion" (PDF). Radiology. 154 (2): 433–441. doi:10.1148/radiology.154.2.3966130. PMID 3966130.

- ^ "CHAPTER-13". www.cis.rit.edu. Retrieved 2020-04-13.

- ^ Bryant, D. J. (August 1984). "Measurement of Flow with NMR Imaging Using a Gradient Pulse and Phase Difference Technique" (PDF). Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography. 8 (4): 588–593. doi:10.1097/00004728-198408000-00002. PMID 6736356. S2CID 8700276.

- ^ Kramer; Grist (Nov 2012). "Peripheral MR Angiography". Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 20 (4): 761–76. doi:10.1016/j.mric.2012.08.002. PMID 23088949.

- ^ Leiner, Tim; Habets, Jesse; Versluis, Bastiaan; Geerts, Liesbeth; Alberts, Eveline; Blanken, Niels; Hendrikse, Jeroen; Vonken, Evert-Jan; Eggers, Holger (2013-04-17). "Subtractionless first-pass single contrast medium dose peripheral MR angiography using two-point Dixon fat suppression". European Radiology. 23 (8): 2228–2235. doi:10.1007/s00330-013-2833-y. ISSN 0938-7994. PMID 23591617. S2CID 2635492.

- ^ Blatter, D D; Bahr, A L; Parker, D L; Robison, R O; Kimball, J A; Perry, D M; Horn, S (December 1993). "Cervical carotid MR angiography with multiple overlapping thin-slab acquisition: comparison with conventional angiography". American Journal of Roentgenology. 161 (6): 1269–1277. doi:10.2214/ajr.161.6.8249741. ISSN 0361-803X. PMID 8249741.

External links

- Magnetic+Resonance+Angiography at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)