Léon M'ba

Léon M'ba | |

|---|---|

Léon M'ba in 1964 | |

| 1st President of Gabon | |

| In office 12 February 1961 – 28 November 1967 | |

| Vice President | Paul-Marie Yembit Albert-Bernard Bongo |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Omar Bongo |

| 1st Prime Minister of Gabon | |

| In office 27 February 1959 – 21 February 1961 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Léon Mébiame (as Prime Minister in 1975) |

| Vice President of the Government Council of French Gabon | |

| In office 21 May 1957 – 1959 | |

| Governor | Louis Sanmarco |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished (succeeded by Vice President of Gabon) |

| Mayor of Libreville | |

| In office 1956–1957 | |

| Member of the Territorial Assembly of French Gabon | |

| In office 1952–1956 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Gabriel Léon M'ba 9 February 1902 Libreville, French Congo (now Gabon) |

| Died | 28 November 1967 (aged 65) Paris, France |

| Nationality | Gabonese |

| Political party | Comité Mixte Gabonais, Bloc Démocratique Gabonais |

| Spouse | Pauline M'ba[1][2] |

Gabriel Léon M'ba[needs IPA][3] (9 February 1902 – 28 November 1967)[4] was a Gabonese politician who served as both the first Prime Minister (1959–1961) and President (1961–1967) of Gabon.

A member of the Fang ethnic group, M'ba was born into a relatively privileged village family. After studying at a seminary, he held a number of small jobs before entering the colonial administration as a customs agent. His political activism in favor of black people worried the French administration, and as a punishment for his activities, he was issued a prison sentence after committing a minor crime that normally would have resulted in a small fine. In 1924, the administration gave M'ba a second chance and selected him to head the canton in Estuaire Province. After being accused of complicity in the murder of a woman near Libreville, he was sentenced in 1931 to three years in prison and 10 years in exile. While in exile in Oubangui-Chari, he published works documenting the tribal customary law of the Fang people. He was employed by local administrators, and received praise from his superiors for his work. He remained a persona non grata to Gabon until the French colonial administration finally allowed M'ba to return his native country in 1946.

After returning from exile, he began his political ascent by founding the Gabonese Mixed Committee. After his party broke ties with the French Communist Party in 1951, it was allowed to run in French Gabon elections and he was elected to the Territorial Assembly in 1952. After becoming mayor of the capital city, Libreville, in 1956, M'ba quickly rose to prominence and was appointed the vice-president of the governor's council on 21 May 1957, the highest position held by a native African in French Gabon. In 1958, he directed an initiative to include Gabon in the Franco-African community further than before.

After independence, he served as the first Prime Minister of Gabon from 27 February 1959 until 21 February 1961. He became the first President of Gabon on 17 August 1960. Political nemesis Jean-Hilaire Aubame briefly assumed the office of president through a coup d'état in February 1964, but order was restored days later when the French intervened. M'ba was reelected in March 1967, but died of cancer in November 1967 and was succeeded by his vice president, Albert-Bernard Bongo.

Early life

A member of the Fang ethnic tribe,[5] M'ba was born on 9 February 1902 in Libreville, Gabon.[6] His father, a small business manager[6] and village chief,[7] once worked as the hairdresser to Franco-Italian explorer Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza.[5] His mother, Louise Bendome, was a seamstress.[5] Both were educated[8] and were among the first "evolved couples" in Libreville.[9] M'ba's brother also played an important role in the colonial hierarchy; he was Gabon's first Roman Catholic priest.[7]

In 1909, M'ba joined a seminary[5] to receive his primary education. From 1920, he was employed as a store manager, a lumberjack and trader before entering the French colonial administration as a customs agent.[9] Despite his good job performance, M'ba's activism in helping black Gabonians,[9] particularly for the Fangs, worried his superiors. In September 1922, M'ba wrote to Edmond Cadier, Lieutenant-Governor of Gabon:

"If on the one hand, the fundamental duty of educating the Fangs is consistent with Gabon's evident economic, military, and even political interests, on the other side, growing in human dignity and the increase of their material well-being do stay, Mr. Governor, the first legitimization of the French authority on them."[10][11]

His remarks upset authorities, and he suffered the consequences in December 1922, when he was sentenced to prison after having committed a minor crime of providing a colleague with falsified documents.[10]

Under the colonial administration

Chef de canton

In either 1924[8] or 1926,[12] M'ba reconciled with colonial authorities and was chosen to succeed the deceased chef de canton (similar to a village chief) of Libreville's Fang neighbourhood.[7] As the leader of a group of young Libreville intellectuals, he ignored the advice of elder Fangs and quickly gained a reputation as a strong, confident, and able-minded man.[8] He once wrote in a letter that he was "[m]issioned to enforce public order and defend the general interest" and that he did "not accept that people transgress the orders received from the authority that I represent."[8]

M'ba did not have an idealist vision of his job; he saw it as a way to become wealthy.[12] With his colleague Ambamamy, he forced labour on the residents of the canton for his personal use, to cover his large expenditures. The colonial administration was aware of the embezzlement, but they chose to overlook it.[12] However, beginning in 1929, the colonial administration started to investigate his activities after they intercepted one of his letters to a Kouyaté, secretary for the Ligue des droits de l'homme, who was accused of being an ally of the Comintern. Despite this suspected Communist alliance, the French authorities did not oppose M'ba's appointment as head chief of the Estuaire Province by his colleagues.[13]

In those years, M'ba, a member of the Ligue,[14] distanced himself from Roman Catholicism, but did not break completely with his faith. He instead became a follower of the Bwiti[9] religious sect, which Fangs were particularly receptive to.[15][16] He believed this would help revitalise a society which he felt had been damaged by the colonial administration.[14] In 1931, the sect was accused of murdering a woman whose remains were discovered outside a market in Libreville.[15] Accused of complicity, even though his involvement in the crime was not proven, M'ba was removed from power[13] and sentenced to three years in prison and ten years of exile.[9] Officially this was for embezzlement of tax revenues and his abusive treatment of the local labour force.[13]

Exile in Oubangui-Chari

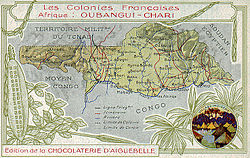

While exiled in the French territory of Oubangui-Chari, first in the towns of Bambari and then Bria,[17] he continued to exert influence among Fangs via correspondence with his compatriots in Libreville. Worried by the situation, Governor-General Antonetti ordered in 1934, at the end of his prison sentence, that M'ba be placed under surveillance.[18]

During his years in exile, he wrote about the customary rights of the Fang people in the "Essai de droit coutumier pahouin" (English: Essay of Pahouin customary rights) and published it in Bulletin de la société des recherches congolaises in 1938.[19] This work quickly became the main reference on Fang tribal customary law.[20] By 1939, the native ex-chief remained a persona non grata to Gabon, as stated in the letter from the head of the Estuarie Department, Assier de Pompignan:

For Léon M'Ba not only was the leader who had claimed for personal use the colony's money. He enjoyed also a considerable amount of prestige, as his congeners could see, which he got from witchcraft activities he practiced. As he was intelligent, he exploited this situation to extort the people he had to administrate also the cabal which he had formed. But on the other hand, he knew how to flatter the representatives of the authority, beguiling their vigilance and gaining their confidence. That is why he had, years before, committed all kinds of abuses without ever being otherwise worried about it.[19][21]

In spite of being in exile, M'ba was employed by local administrators. Placed in secondary offices and having no proper power, he was an accomplished and valuable employee. Thanks to praiseworthy reports from his superiors, he was once again seen as a reliable indigenous element on which the colonial administration could rely on.[22] In 1942, a sentence reduction was granted to him.[17] Following his release, he became a civil servant in Brazzaville, where his prestige increased.[23]

Political ascension

Return to Gabon and local politician

In 1946, M'ba returned to Gabon, where he was greeted exultantly by his friends.[17] He was not reinstated as chef de canton; instead, he obtained an important position as store manager for the English trading house John Holt.[17][24] That same year, he founded the Gabonese Mixed Committee (CMG), a political party close to the African Democratic Rally (RDA), an inter-African party led by Félix Houphouët-Boigny.[16][25] The party's main objective was to obtain autonomy for its member states and oppose the Senegalese leader Léopold Sédar Senghor's idea of federalism.[16] Playing on his past as a former exile, and through the network of Bwiti followers, M'ba managed to rally support from the Fang and Myènè peoples.[26] His goal was to win indigenous administrative and judicial posts.[27]

Based on his success in Libreville, M'ba aspired, at one point, to become the head of the region, an idea which many notable Fangs supported during the Pahouin congress at Mitzic in February 1947.[28] However, the colonial authorities refused to give him the position. Due to his relations with the RDA, which was linked to the French Communist Party, M'Ba was seen as a communist and propagandist in the colony; for the authorities, these suspicions had been confirmed when M'ba was involved in the 1949 RDA congress in Abidjan.[29]

In 1951, the CMG decided to break its ties with the Communists, siding with the moderate position favored by Houphouët-Boigny while he did the same.[30] At the same time M'ba, while maintaining his "rebellious" image to the electorate, became close with the French administration.[31] However, the administration was already supporting his main opponent, Congressman Jean-Hilaire Aubame, who was M'ba's protégé and his half-brother's foster son.[26] In the legislative elections of 17 June 1951, Aubame was easily re-elected, as M'ba only received 3,257 votes, just 11% of the electorate.[32] In the territorial elections of March 1952, Aubame's Gabonese Democratic and Social Union (UDSG) won 14 of the 24 contested seats, against two for the CMG; however, the CMG received 57% of the votes cast in Libreville.[32]

Rise to power

Initially rejected by the Territorial Assembly, M'ba allied himself with French representatives in the assembly.[32] However, using his charismatic traits and his reputation as a "man of the people", he managed to win a seat there in 1952.[33]

He left the CMG to join the Gabonese Democratic Bloc (BDG) led by Paul Gondjout in 1954,[33] whom M'ba intended to overthrow.[34] Gondjout, the secretary of the BDG, appointed M'ba secretary-general and formed a long term alliance against Aubame.[35] In the legislative elections of 2 January 1956, M'ba received 36% of the votes versus 47% for Aubame.[36] Though not elected, M'ba became the leader of the indigenous territory, and some of the UDSG began to ally themselves with him.[37]

In the municipal elections of 1956, M'ba received support from the French logging industry, especially Roland Bru, and was elected mayor of Libreville[33] with 65.5% of the vote. On 23 November he was appointed the first mayor of the capital.[38] This has been cited as the BDG's first significant victory over the UDSG.[35] In the French practice of holding multiple posts known as cumul des positions, M'ba served as both mayor and deputy.[33]

In the territorial elections of March 1957, his reputation as a "forester's man" worked against him;[33] the BDG finished second again, winning 16 of the 40 contested seats, against 18 for the UDSG.[39] Bru and other French foresters bribed several UDSG deputies to switch their political party to the BDG. M'ba's party won 21 seats against 19 for Aubame's party after a recount. However, in the absence of an absolute majority, both parties were obliged to submit on 21 May 1957, a list of individuals that both agreed were suitable for election into the government.[40] That same day, M'ba was appointed vice president of the government council under the French governor.[16] Soon, divisions grew within the government, and Aubame resigned from his position and filed a motion of censure against the government. The motion was rejected by a 21–19 vote.[41] With M'ba's victory, many elected UDSG members joined the parliamentary majority, giving the party a majority with 29 of the 40 legislative seats. Well installed in the government, he slowly began to reinforce his power.[42]

After voting in favor of the Franco-African Community, similar to the British Commonwealth, in the constitutional referendum of 28 September 1958,[43] Gabon became pseudo-politically independent.[23] French journalist Pierre Péan asserted that M'ba secretly tried to prevent Gabonese independence; instead, he lobbied for it to become an overseas territory of France.[44] In December 1958, the Assembly voted to establish the legislature, and then promulgated the constitution of the Republic of Gabon on 19 February 1959.[43] On 27 February, M'ba was appointed Prime Minister.[45] After M'ba openly declared for the departmentalization of Gabon in November 1959,[46] Jacques Foccart, Charles de Gaulle's spin doctor for African policy, told him that this solution was unthinkable.[47] M'ba then decided to adopt a new flag by affixing the design of the national tree, the Angouma, over the French flag. Again, Foccart, as a loyal Frenchman, refused.[47]

From July 1958, a third political force tried to establish itself in Gabon: the Parti d'Union Nationale Gabonais (PUNGA), led by René-Paul Sousatte and Jean-Jacques Boucavel, created attempting to unite the southern Gabonese against the established BDG and UDSG. It was also supported by former UDSG members, "radical" students, and trade unionists.[35] Though it voted against the constitutional referendum,[48] PUNGA organised several events geared toward gaining independence and the holding of more parliamentary elections, which were also supported by the UDSG.[43] In March 1960, after independence had already been obtained, M'ba cracked down on PUNGA, claiming its goal had already been reached. He filed an arrest warrant for Sousatte for conspiring against him and searched the houses of UDSG members, who he accused of complicity. Intimidated, three deputies of the UDSG joined the majority.[49]

President of Gabon

Consolidation of power

On 19 June 1960, legislative elections were organised through the scrutin de liste voting system, a form of bloc voting in which each party offers a list of candidates who the population vote for; the list that obtains a majority of votes is declared the winner and obtains all the contested seats. Through the redistricting of district and constituency boundaries, the BDG arbitrarily received 244 seats, while the UDSG received 77.[50] In the month before full political independence of Gabon was achieved on 13 August, M'ba signed 15 cooperation agreements with France, pertaining to national defense, technical cooperation, economic support, access to materials, and national stability.[23] On 17 August, independence was proclaimed. However, the Prime Minister realistically declared on 12 August, "We must not waste our chances by imagining that with independence, we now own a powerful fetish that will fulfill our wishes. In believing that with independence everything becomes easy and possible, there is a danger of descending into anarchy, disorder, poverty, famine."[51][52]

M'ba aspired to establish a democratic regime, which, in his view, was necessary for the development and attraction of investments in Gabon. He attempted to reconcile the imperatives of democracy and the necessity for a strong and coherent government.[53] Yet in practice, the regime showed a fundamental weakness in attaining M'ba's goal in which he, who had by this time become known as "the old man",[54] or "the boss", would have a high degree of authority. A cult of personality developed steadily around M'ba; songs were sung in his praise and stamps and loincloths were printed with his effigy.[45] His photograph was displayed in stores and hotels across Gabon, in government buildings hung next to that of de Gaulle.[55]

In November 1960, a crisis broke out within the majority party. After deciding to reshuffle the cabinet without consulting Parliament, the president of the National Assembly, Paul Gondjout, a previous ally of M'ba's, filed a motion of censure.[56] Gondjout supposedly hoped to benefit from a balance of power modified to his own advantage, and specifically sought the establishment of a strong parliament and a prime minister with executive power.[57] M'ba, who did not share these ideas, reacted repressively. On 16 November, under the pretext of a conspiracy, he declared a state of emergency, ordering the internment of eight BDG opponents and the dissolution of the National Assembly the day after.[56] Electors were asked to vote again on 12 February 1961.[58] Gondjout was sentenced to two years in prison. Sousatte, who also opposed the constitution, was also sentenced to the same amount of jail time.[59] Upon their releases, M'ba appointed Gondjout president of the economic council and Sousatte Minister of Agriculture, both mostly symbolic posts.[60]

"Hyperprésident" of Gabon

On 4 December, M'ba was elected to replace Gondjout as Secretary General of the BDG.[61] He turned to the opposition to strengthen his position.[58] With Aubame, he formed a number of sufficiently balanced political unions to appeal to the electorate.[62] On 12 February, they won 99.75% of the vote.[63] The same day, M'ba was elected President of Gabon, being the only candidate.[62] In thanks for his help, M'ba appointed Aubame as foreign minister to replace André Gustave Anguilé.[63]

On 21 February 1961, a new constitution was unanimously adopted,[62] providing for a "hyperpresidential" regime.[64] M'ba now had full executive powers: he could appoint ministers whose functions and responsibilities were decided by him; he could dissolve the National Assembly by choice or prolong its term beyond the normal five years; he could declare a state of emergency when he believed the need arose, though for this amendment he would have to consult the people via a referendum. This was, in fact, very similar to the constitution adopted in favor of Fulbert Youlou at roughly the same time.[65] A report from the French secret service summarized the situation as follows:

He regarded himself as a truly democratic leader; nothing irritated him more than being called a dictator. Still, he wasn't happy until he had the constitution rewritten to give him virtually all power and transforming the parliament into high-priced scenery that could be bypassed as needed.[57][66]

The new constitution and the National Union (a political union they founded) suspended the quarrels between M'ba and Aubame from 1961 to 1963. Despite this, political unrest grew within the population,[67] and many students held demonstrations on the frequent dissolutions of the National Assembly and the general political attitude in the country.[68] The president did not hesitate to enforce the law himself; with a chicotte, he whipped citizens who did not show respect for him, including passersby who "forgot" to salute him.[47] In addition, in February 1961, he decreed the internment of approximately 20 people for these demonstrations.[61]

On 9 February 1963, the President pardoned those arrested during the political crisis of November 1960.[69] On 19 February, he broke his ties with Aubame; all UDSG representatives were dismissed, with the exception of M'ba supporter Francis Meye.[70] In an attempt to oust Aubame from his legislative seat, M'ba appointed him President of the Supreme Court on 25 February.[69] Thereafter, M'ba claimed that Aubame had resigned from the National Assembly, citing incompatibility with parliamentary functions. Aubame resolved the problem by resigning from his post on the Supreme Court, complicating matters for M'ba.[71] Faced with reports of tension between the government and the National Assembly, even though 70% of it were BDG members, the Gabonese president dissolved the legislature on 21 January 1964[72] as an "economy measure".[73]

The electoral conditions were announced as such: The election 67 districts were reduced to 47. M'ba disqualified Aubame by announcing anyone who held a post recently was banned. Any party would have to submit 47 candidates who had to pay US$160 or none at all. Thus, over US$7,500 would be deposited without considering campaign expenses. M'ba's idea was that no party other than his would have the money to enter candidates.[74] In response to this, the opposition announced its refusal to participate in elections that they did not consider fair.[72]

1964 Gabon coup d'état

From the night of 17 February to the early morning of 18 February 1964, 150 Gabonese military personnel, headed by Lieutenant Jacques Mombo and Valére Essone, arrested President of the National Assembly Louis Bigmann,[75] French commanders Claude Haulin and Major Royer,[76] On Radio Libreville, the military announced to the Gabonese people that a coup d'état had taken place, and that they required technical assistance and told the French not interfere in this matter. M'ba was instructed to broadcast a speech acknowledging his defeat.[77] "The D-Day is here, the injustices are beyond measure, these people are patient, but their patience has limits", he said. "It came to a boil."[77][78]

During these events, no gunshots were fired. The people did not react strongly, which according to the military, was a sign of approval.[79] A provisional government was formed, and the presidency was offered to Aubame. The government was composed of civilian politicians from both the UDSG and BDG, such as Paul Gondjout.[80] The plotters were content to ensure security for civilians. The small Gabonese army did not intervene in the coup; composed mostly of French officers, they remained in their barracks.[47]

Second Lieutenant Ndo Edou gave instructions to transfer M'ba to Ndjolé, Aubame's electoral stronghold. However, due to heavy rain, the deposed president and his captors took shelter in an unknown village. The next morning they decided to take him over the easier road to Lambaréné. Several hours later, they returned to Libreville.[81] The new head of government quickly contacted French ambassador Paul Cousseran, to assure him that the property of foreign nationals was protected and to ask him to prevent any French military intervention.[82]

But in Paris, de Gaulle decided otherwise.[47] M'ba was one of the most loyal allies to France in Africa. While visiting France in 1961, M'ba said: "All Gabonese have two fatherlands: France and Gabon."[83][84] Moreover, under his regime, Europeans enjoyed particularly friendly treatment.[84] The French authorities therefore decided, in accordance with signed Franco-Gabon agreements, to restore the legitimate government.[47] Intervention could not commence without a formal request to the Head of State of Gabon. Since M'ba was otherwise occupied, the French contacted the Vice President of Gabon, Paul Marie Yembit, who had not been arrested.[82] However, he remained unaccounted for; therefore, they decided to compose a predated letter that Yembit would later sign, confirming their intervention.[47] Less than 24 hours later, French troops stationed in Dakar and Brazzaville landed in Libreville and restored M'ba back into power.[85][86] Over the course of the operation, one French soldier was killed, while 15 to 25 died on the Gabonese side.[85]

Under the tutelage of France

After he was reinstated into power, M'ba refused to consider the coup was directed against him and his regime.[87] He believed it was a conspiracy against the state. Soon, however, anti-government demonstrations sprang up, with slogans such as "Léon M'ba, président des Français!" (English: "Léon M'ba, president of the French") or ones that called for the end of the "dictatorship".[88] They showed solidarity after Aubame was charged on 23 March for his alleged involvement in the coup d'état.[87] Despite the fact that he did not participate in the planning of the coup, Aubame was sentenced at his trial to 10 years of hard labor and 10 years of exile.[89]

Despite these events, legislative elections, which were planned before the coup, were held in April 1964. The major opposition parties were deprived of their leaders, who were prevented from participating in the elections due to their involvement in the coup.[90] The UDSG disappeared from the political scene, and the opposition consisted of parties that lacked national focus and maintained only regional or pro-democracy platforms. The opposition still won 46% of the votes and 16 of 47 seats, while the BDG received 54% of the vote and 31 seats in the assembly.[91]

His French friends constantly surrounded him, protecting or providing him with counsel. A presidential guard was created by Bob Maloubier, a former French secret agent, and co-financed by French oil groups.[47] The oil groups, active in the country since 1957, had strengthened their interests in 1962 after the discovery of offshore oil deposits.[92] Gabon quickly became a major oil supplier for France. They carried such influence in Gabon that following the February 1964 coup, the decision to seek military intervention was taken by the CEO of Union Générale des Pétroles (UGP; now known as Elf Aquitaine), Pierre Guillaumat, Foccart, and other French businessmen and leaders.[92][93] Later on, another UGP executive, Guy Ponsaillé, was appointed as political adviser to the president and became M'ba's representative in discussions with French companies. However, the Gabonese president was afraid of internal strife or assassination, so he remained secluded inside his heavily defended presidential palace. Ponsaillé helped M'ba obtain support from political moderates and accompanied him in his visits around the country in order to restore his reputation among the Gabonese people.[47]

French ambassador Cousseran and American ambassador Charles F. Darlington, suspected of sympathizing with Aubame, left shortly after the coup.[94] The new French ambassador François Simon de Quirielle, a "traditional diplomat", was determined not to interfere in the internal affairs of Gabon.[95] After a few months of misunderstandings with de Quirielle, M'ba contacted Foccart to tell him that he could no longer work with the Ambassador. Foccart recounted the events in his memoirs, Foccart Speaks:

Do you realise, exploded the Gabonese President, I'm receiving de Quirielle to summarize the situation with him. I'm asking him his thoughts about this or that [Gabonese] minister, about this or that in the agenda [in Gabon's political interior]. And guess what his answer was? Mister President, I'm really sorry, but the duties I hold forbid me from intervening in the affairs of your country.[95][96]

As a result of this incident, Foccart appointed a "colonialist", Maurice Delauney, as the new French Ambassador to Gabon.[95]

Succession and legacy

From 1965, the French began looking for a successor for M'ba, who was aging and sick.[97] They found the perfect candidate in Albert Bernard Bongo (later known as Alhaji Omar Bongo Ondimba), a young leader in the President's cabinet.[47] Bongo was personally "tested" by General de Gaulle in 1965, during a visit to the Élysée Palace.[98] Confirmed as M'ba's successor, Bongo was appointed on 24 September 1965 as Presidential Representative and placed in charge of defence and coordination.[47]

In August 1966, M'ba was admitted to the Hôpital Charles Bernard, a hospital in Paris.[99] Despite his inability to govern, the president clung to his power. Only after a long insistence by Foccart did M'ba agree to appoint Bongo as Vice President in replacement of Yembit, announcing his decision through a radio and television message recorded in his room on 14 November 1966.[100] A constitutional reform in February 1967 legitimized Bongo as M'ba's successor.[99] The preparations for the succession were finalized by the early legislative and presidential elections held on 19 March 1967. Since no one dared to stand on the opposition ticket, M'ba was reelected with 99.9% of the vote, while the BDG won all seats in the Assembly.[101]

On 28 November 1967, just days after he took his presidential oath at the Gabonese embassy, M'ba died of cancer in Paris, where he had been treated since August of that year. He was survived by his wife, Pauline M'ba, and 11 children.[54] The day after M'ba's death, Bongo constitutionally succeeded him as President of Gabon.[99] Gabon's main airport, the Leon M'ba International Airport, was later named for him.

Forty years after his death, the Léon M'ba Memorial was built in Libreville to honor his memory. President Bongo laid the cornerstone for the Memorial on 9 February 2007, and it was inaugurated by Bongo on 27 November 2007.[102] In February 2008, it was opened to the public.[103] In addition to serving as a mausoleum for M'ba,[102] the Memorial is a cultural center.[103]

Notes

- ^ In his book, African Betrayal, Charles Darlington mentions that M'ba had several wives, under the traditional Gabonese practice of polygamy. Other than Pauline, their names are unknown.

- ^ Darlington & Darlington 1968, p. 13

- ^ His surname is also written as M'Ba and Mba.

- ^ "Leon M'Ba, President of Gabon, Dies", Chicago Tribune, 29 November 1967, p2-6

- ^ a b c d Biteghe 1990, p. 24.

- ^ a b Bernault 1996, p. 215.

- ^ a b c Appiah & Gates 1999, p. 1278.

- ^ a b c d Bernault 1996, p. 216.

- ^ a b c d e Biteghe 1990, p. 25.

- ^ a b Keese 2004, p. 144.

- ^ Si d'un côté le devoir fondamental d'instruire les Pahouins concorde par su[r]croît avec les intérêts économiques, militaires et même politiques les plus évidents du Gabon, de l'autre côté leur accroissement en dignité humaine et l'augmentation de leur bien-être matériel, demeurent, Monsieur le Gouverneur, la légitimation première de l'autorité française sur eux.

- ^ a b c Keese 2004, p. 145.

- ^ a b c Keese 2004, p. 146.

- ^ a b Reed 1987, p. 293

- ^ a b Bernault 1996, p. 218.

- ^ a b c d Taylor 1967, p. 140.

- ^ a b c d Biteghe 1990, p. 26.

- ^ Keese 2004, p. 147.

- ^ a b Keese 2004, p. 148.

- ^ Bernault 1996, p. 217.

- ^ C'est que Léon M'Ba n'était pas seulement le chef qui s'était approprié pour des besoins personnels les deniers de la colonie. Il jouissait aussi aux yeux de ses congénères d'un prestige considérable qu'il tirait des pratiques de sorcellerie auxquelles il s'adonnait. Comme il était intelligent, il exploitait cette situation pour rançonner les gens qu'il avait charge d'administrer et qui le redoutaient ainsi que la camarilla dont il s'était entouré. Mais il savait, par contre, amadouer les représentants de l'autorité, endormir leur vigilance et capter leur confiance. C'est ce qui explique qu'il ait, des années devant, commis toutes sortes d'exactions sans jamais être autrement inquiété.

- ^ Keese 2004, p. 149.

- ^ a b c Pederson, Nicholas (May 2000), French Involvement in Gabon, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, archived from the original on 2 September 2007, retrieved 9 August 2008

- ^ Rich, Jeremy (2004), "Troubles at the Office: Clerks, State Authority, and Social Conflict in Gabon, 1920-45", Canadian Journal of African Studies, 38 (1), Canadian Association of African Studies: 58–87, doi:10.2307/4107268, JSTOR 4107268, OCLC 108738271.

- ^ Bernault 1996, p. 220.

- ^ a b Bernault 1996, p. 222.

- ^ Keese 2004, p. 150.

- ^ Keese 2004, p. 151.

- ^ Keese 2004, p. 153.

- ^ Reed 1987, p. 294

- ^ Bernault 1996, p. 223.

- ^ a b c Bernault 1996, p. 224.

- ^ a b c d e Yates 1996, p. 103.

- ^ Biteghe 1990, p. 28.

- ^ a b c Reed 1987, p. 295.

- ^ Bernault 1996, p. 227.

- ^ Keese 2004, p. 159.

- ^ Bernault 1996, p. 228.

- ^ Bernault 1996, p. 261.

- ^ Bernault 1996, p. 262.

- ^ Bernault 1996, p. 263.

- ^ Bernault 1996, p. 293.

- ^ a b c Bernault 1996, p. 294.

- ^ Péan 1983, pp. 40–42

- ^ a b Biteghe 1990, p. 29.

- ^ Keese 2004, p. 161.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k (in French) Pesnot, Patrick (producer) & Billoud, Michel (director) (10 March 2007), 1964, le putsch raté contre Léon M'Ba président du Gabon, France Inter. Retrieved on 7 September 2008.

- ^ Bernault 1996, p. 269.

- ^ Bernault 1996, p. 296.

- ^ Bernault 1996, p. 297.

- ^ Biteghe 1990, p. 33.

- ^ Ne gaspillons pas notre chance en imaginant qu'avec l'indépendance, nous détenons désormais un fétiche tout puissant qui va combler tous nos vœux. En croyant qu'avec l'indépendance tout est possible et facile, on risque de sombrer dans l'anarchie, le désordre, la misère, la famine.

- ^ Biteghe 1990, p. 35.

- ^ a b "Léon M'ba, President of Gabon Since Independence, Dies at 65", The New York Times, p. 47, 19 November 1967, retrieved 7 September 2008

- ^ Matthews 1966, p. 132.

- ^ a b Bernault 1996, p. 300.

- ^ a b Keese 2004, p. 162.

- ^ a b Biteghe 1990, p. 41.

- ^ Yates 1996, p. 105

- ^ Yates 1996, p. 106

- ^ a b Bernault 1996, p. 301.

- ^ a b c Biteghe 1990, p. 44.

- ^ a b Biteghe 1990, p. 42.

- ^ Biteghe 1990, p. 46

- ^ Matthews 1966, p. 123

- ^ Se voulant et se croyant sincèrement démocrate, au point qu'aucune accusation ne l'irrite davantage que celle d'être un dictateur, il n'en a pas moins eu de cesse qu'il n'ait fait voter une constitution lui accordant pratiquement tous les pouvoirs et réduisant le parlement au rôle d'un décor coûteux que l'on escamote même en cas de besoin.

- ^ Biteghe 1990, p. 52

- ^ Biteghe 1990, p. 49

- ^ a b Biteghe 1990, p. 54.

- ^ Biteghe 1990, p. 53.

- ^ Biteghe 1990, p. 55.

- ^ a b Biteghe 1990, p. 59.

- ^ "De Gaulle to the Rescue", Time, 28 February 1964, archived from the original on 1 December 2007, retrieved 6 August 2008.

- ^ Darlington & Darlington 1968, pp. 123–124.

- ^ Giniger, Henry (20 February 1964), "Gabon Insurgents Yield as France Rushes in Troops", The New York Times, retrieved 17 September 2008

- ^ Garrison, Lloyd (21 February 1964), "Gabon President Resumes Office: Mba, Restored by French, Vows 'Total Punishment' for All Who Aided Coup", The New York Times, p. 1, retrieved 8 September 2008

- ^ a b Biteghe 1990, p. 62.

- ^ "Le jour J est arrivé, les injustices ont dépassé la mesure, ce peuple est patient, mais sa patience a des limites... il est arrivé à bout."

- ^ Biteghe 1990, p. 63.

- ^ Biteghe 1990, p. 64.

- ^ Darlington & Darlington 1968, p. 134

- ^ a b Biteghe 1990, p. 19.

- ^ "Tout Gabonais a deux patries : la France et le Gabon."

- ^ a b Biteghe 1990, p. 23.

- ^ a b Bernault 1996, p. 19.

- ^ Grundy, Kenneth W. (October 1968), "On Machiavelli and the Mercenaries", The Journal of Modern African Studies, 6 (3): 295–310, doi:10.1017/S0022278X00017420, JSTOR 159300, S2CID 154814661.

- ^ a b Biteghe 1990, p. 100.

- ^ Biteghe 1990, p. 92.

- ^ Biteghe 1990, p. 104.

- ^ Biteghe 1990, p. 94.

- ^ Biteghe 1990, p. 96.

- ^ a b Gaston-Breton, Tristan (9 August 2006), "Pierre Guillaumat, Elf et la " Françafrique "", Les Échos (in French), retrieved 2 August 2008

- ^ Yates 1996, p. 112.

- ^ Biteghe 1990, p. 71.

- ^ a b c Foccart & Gaillard 1995, p. 277.

- ^ Vous vous rendez compte, explose le président gabonais, je reçois de Quirielle pour faire un tour d'horizon avec lui. Je lui demande ce qu'il pense de tel ministre [gabonais], de telle question qui est à l'ordre du jour [de la politique intérieure du Gabon]. Devinez ce qu'il me réplique! Monsieur le président, je suis désolé, les fonctions que j'occupe m'interdisent d'intervenir comme vous me le demandez dans les affaires de votre pays.

- ^ Foccart 1997, p. 58.

- ^ Yahmed, Béchir Ben (17 July 2001), "Bongo par lui-même", Jeune Afrique (in French), retrieved 4 August 2008.

- ^ a b c Reed 1987, p. 299

- ^ Biarnes 2007, p. 173.

- ^ Biarnes 2007, p. 174.

- ^ a b "REALISATIONS: Mémorial Léon Mba", Mosa Concept News (in French), 2007, retrieved 14 September 2008[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Batassi, Pierre Eric Mbog (13 September 2009), "Gabon: Mémorial Léon Mba, un devoir de mémoire réussi", Afrik.com (in French), retrieved 14 September 2008.

References

- Appiah, Kwame Anthony; Gates, Henry Louis Jr., eds. (1999), Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience, New York: Basic Books, ISBN 0-465-00071-1, OCLC 41649745.

- Bernault, Florence (1996), Démocraties ambiguës en Afrique centrale: Congo-Brazzaville, Gabon, 1940–1965 (in French), Paris: Karthala, ISBN 2-86537-636-2, OCLC 36142247.

- Biarnes, Pierre (2007), Si tu vois le margouillat: souvenirs d'Afrique (in French), Paris: Harmattan, ISBN 978-2-296-03320-7, OCLC 159956045.

- Biteghe, Moïse N'Solé (1990), Echec aux militaires au Gabon en 1964 (in French), Paris: Chaka, ISBN 2-907768-06-9, OCLC 29518659.

- Darlington, Charles F.; Darlington, Alice B. (1968). African Betrayal. D. McKay Company.

- Etoughe, Dominique (1990), Justice indigène et essor du droit coutumier au Gabon: La contribution de Léon M'ba, 1924–1938 (in French), Paris: L'Harmattan, ISBN 2-296-04404-2, OCLC 182917488.

- Foccart, Jacques; Gaillard, Philippe (1995), Foccart parle: Entretiens avec Philippe Gaillard (in French), vol. 1, Paris: Fayard–Jeune Afrique, ISBN 2-213-59419-8, OCLC 32421474.

- Foccart, Jacques (1997), Journal de l'Élysée: Tous les soirs avec de Gaulle (1965–1967) (in French), vol. 1, Paris: Fayard–Jeune Afrique, ISBN 2-213-59565-8, OCLC 37871981.

- Keese, Alexander (2004), "L'évolution du leader indigène aux yeux des administrateurs français: Léon M'Ba et le changement des modalités de participation au pouvoir local au Gabon, 1922–1967", Afrique & Histoire (in French), 2 (1): 141–170, doi:10.3917/afhi.002.0141, ISSN 1764-1977.

- Matthews, Ronald (1966), African Powder Keg: Revolt and Dissent in Six Emergent Nations, London: The Bodley Head, OCLC 246401461.

- Péan, Pierre (1983), Affaires africaines (in French), Paris: Fayard, ISBN 2-213-01324-1, OCLC 10363948.

- Reed, Michael C. (June 1987), "Gabon: A Neo-Colonial Enclave of Enduring French Interest", The Journal of Modern African Studies, 25 (2), Cambridge University Press: 283–320, doi:10.1017/S0022278X00000392, JSTOR 161015, OCLC 77874468, S2CID 153880808.

- Taylor, Sidney, ed. (1967), The New Africans: A Guide to the Contemporary History of Emergent Africa and Its Leaders, New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, OCLC 413862.

- Yates, Douglas A. (1996), The Rentier State in Africa: Oil Rent Dependency and Neocolonialism in the Republic of Gabon, Trenton, New Jersey: Africa World Press, ISBN 0-86543-521-9, OCLC 34543635.