Kaizen

Kaizen (Japanese: 改善, "improvement") is a concept referring to business activities that continuously improve all functions and involve all employees from the CEO to the assembly line workers. Kaizen also applies to processes, such as purchasing and logistics, that cross organizational boundaries into the supply chain.[1] Kaizen aims to eliminate waste and redundancies. Kaizen may also be referred to as zero investment improvement (ZII) due to its utilization of existing resources.[2]

After being introduced by an American, Kaizen was first practiced in Japanese businesses after World War II, and most notably as part of The Toyota Way. It has since spread throughout the world and has been applied to environments outside of business and productivity.[3]

History

In 1947, Edwards Deming, an American statistician, went to Japan to help enhance their production processes. He stressed that quality should be prioritized at every stage of production, achieved through statistical process control. Deming is particularly recognized for his PDCA cycle—Plan, Do, Check, Act—which advises stopping production when deviations occur to identify and resolve issues before continuing. During his time in Japan, he trained hundreds of engineers, managers and executives in his approach.[4]

Deming developed his concepts into what he termed "total quality management," which eventually laid the groundwork for Toyota's Toyota Production System focused on just-in-time manufacturing.[5]

Overview

The Japanese word kaizen means 'improvement' or 'change for better' (from 改 kai - change, revision; and 善 zen - virtue, goodness) without the inherent meaning of either 'continuous' or 'philosophy' in Japanese dictionaries or in everyday use. The word refers to any improvement, one-time or continuous, large or small, in the same sense as the English word improvement.[6] However, given the common practice in Japan of labeling industrial or business improvement techniques with the word kaizen, particularly the practices spearheaded by Toyota, the word kaizen in English is typically applied to measures for implementing continuous improvement, especially those with a "Japanese philosophy". The discussion below focuses on such interpretations of the word, as frequently used in the context of modern management discussions. Two kaizen approaches have been distinguished:[7]

Point kaizen

Point kaizen is one of the most commonly implemented types of kaizen.[citation needed] It happens very quickly and usually without much planning. As soon as something is found broken or incorrect, quick and immediate measures are taken to correct the issues. While these measures are generally small, isolated and easy to implement, they can have a huge impact.

In some cases, it is also possible that the positive effects of point kaizen in one area can reduce or eliminate benefits of point kaizen in some other area.

Examples of point kaizen include a shop inspection by a supervisor who finds broken materials or other small issues, and then asks the owner of the shop to perform a quick kaizen (5S) to rectify those issues, or a line worker who notices a potential improvement in efficiency by placing the materials needed in another order or closer to the production line in order to minimize downtime.

System kaizen

System kaizen is accomplished in an organized manner and is devised to address system-level problems in an organization or any production factory.

It is an upper-level strategic planning method for a short period of time.

Line kaizen

Line kaizen refers to communication of improvements between the upstream and downstream of a process. This can be extended in several ways.

Plane kaizen

This is the next upper level of line kaizen, in that several lines are connected together. In modern terminologies, this can also be described as a value stream, where instead of traditional departments, the organization is structured into product lines or families and value streams. It can be visualized as changes or improvements made to one line being implemented to multiple other lines or processes.

Cube kaizen

Cube kaizen describes the situation where all the points of the planes are connected to each other and no point is disjointed from any other. This would resemble a situation where Lean has spread across the entire organization. Improvements are made up and down through the plane, or upstream or downstream, including the complete organization, suppliers and customers. This might require some changes in the standard business processes as well.

Application

The 5S movement

The 5S are primarily aimed at the workshop workplaces, whereby the workplace is understood as the place where the value-adding processes in the company take place.

- Seiri

- Create order: remove everything that is not necessary from your workspace!

- Seiton

- Love of order: organize things and keep them in their proper place!

- Seiso

- Cleanliness: keep your workplace clean!

- Seiketsu

- Personal sense of order: make 5S a habit by setting standards!

- Shitsuke

- Discipline: make cleanliness and order your personal concern!

The 7M checklist (Ishikawa diagram)

These are the seven most important factors that must be checked again and again:

- Man

- Machine

- Material

- Method

- Milieu/environment

- Management

- Measurability

The original 5M method was expanded to include the last two factors, as the influence of management in the system and measurability are of a certain scope. (See also the Ishikawa diagram as a graphical representation of the 7Ms).

The 7W checklist

The 7W checklist possibly goes back to Cicero as an original tool for rhetoric:

- What is to be done?

- Who does it?

- Why do it?

- How is it done?

- When is it done?

- Where should it be done?

- Why is it not done differently?

Related to the 7W questionnaire is the principle of "Go to the source" (Genchi Genbutsu). This means asking "Why?" 5 times in the event of undesirable results or errors in order to find a solution. Furthermore, managers should get an idea of the situation on site, for example a production process, and not make decisions from afar.

The W questions are used in a wide variety of areas, for example when analyzing texts,[8] as an aid in defining projects[9] as well as in work analysis[10] and, as a result, in defining work content.

In the field of quality management, this principle is used in failure mode and effects analysis to identify potential weaknesses.

The three Mu

The three Mu form the basis for the loss philosophy of the Toyota Production System (TPS). In the context of this loss philosophy, the three Mu are seen as negative focal points of the loss potential and should therefore be avoided.

- Muda

- Waste, see the seven Muda

- Mura

- Deviations in the processes (also imbalance)

- Muri

- Overloading of employees and machines

The seven Muda

The seven types of waste (seven Muda) as typical sources of loss.

The waste itself (Muda) is the obvious cause of losses. A distinction is made between seven types of waste that occur almost everywhere in the company.

- Muda due to overproduction

- Produce more than necessary.

- Muda due to waiting time

- Inactive hands of an employee. Process timing not optimized.

- Muda due to unnecessary transportation

- Movement of materials or products does not add value.

- Muda due to production of faulty parts

- Defective products disrupt the production flow and require expensive rework.

- Muda due to excessive storage

- Finished and semi-finished products, vendor parts and materials stored as inventory do not add value.

- Muda due to unnecessary movement

- Awkward, unergonomic and unnecessary movements consume time, lead to fatigue and increase the risk of injury.

- Muda due to an unfavorable manufacturing process

- The additional equipment of products or services with features that are neither desired nor paid for by the customer.

Just-in-Time (JIT)

- This principle is a logistics-oriented decentralized organization and control concept that aims to supply and dispose of materials for production on demand and thus ensures the precise delivery of raw materials or products of the required quality in the desired quantity (and packaging) to the desired location at the time they are actually needed. This eliminates storage costs; the remaining administrative effort can be reduced to a relative minimum.

- An enhancement of "just-in-time" is the so-called "just in sequence" (JIS). Based on the JIT principle, the products are also delivered to the customer in the correct sequence.

JIT is now standard throughout the automotive industry. It is used, for example, for interior parts (seats, airbags, steering wheels, dashboards) or painted parts. The generally higher transportation and handling costs caused by JIT or JIS are offset by savings in inventory, storage or floor space costs.

Total Productive Maintenance

- Constant monitoring of the production lines

- Attempt to continuously improve the lines

- Elimination of waste of any kind

For more information, see the article Total productive maintenance.

Benefits and tradeoffs

Kaizen is a daily process, the purpose of which goes beyond simple productivity improvement. It is also a process that, when done correctly, humanizes the workplace, eliminates overly hard work (muri), and teaches people how to perform experiments on their work using the scientific method and how to learn to spot and eliminate waste in business processes. In all, the process suggests a humanized approach to workers and to increasing productivity: "The idea is to nurture the company's people as much as it is to praise and encourage participation in kaizen activities."[11] Successful implementation requires "the participation of workers in the improvement."[12] People at all levels of an organization participate in kaizen, from the CEO down to janitorial staff, as well as external stakeholders when applicable. Kaizen is most commonly associated with manufacturing operations, as at Toyota, but has also been used in non-manufacturing environments.[13] The format for kaizen can be individual, suggestion system, small group, or large group. At Toyota, it is usually a local improvement within a workstation or local area and involves a small group in improving their own work environment and productivity. This group is often guided through the kaizen process by a line supervisor; sometimes this is the line supervisor's key role. Kaizen on a broad, cross-departmental scale in companies generates total quality management and frees human efforts through improving productivity using machines and computing power.[citation needed]

While kaizen (at Toyota) usually delivers small improvements, the culture of continual aligned small improvements and standardization yields large results in terms of overall improvement in productivity. This philosophy differs from the "command and control" improvement programs (e.g., Business Process Improvement) of the mid-20th century. Kaizen methodology includes making changes and monitoring results, then adjusting. Large-scale pre-planning and extensive project scheduling are replaced by smaller experiments, which can be rapidly adapted as new improvements are suggested.[citation needed]

In modern usage, it is designed to address a particular issue over the course of a week and is referred to as a "kaizen blitz" or "kaizen event".[14][15] These are limited in scope, and issues that arise from them are typically used in later blitzes.[citation needed] A person who makes a large contribution in the successful implementation of kaizen during kaizen events is awarded the title of "Zenkai". In the 21st century, business consultants in various countries have engaged in widespread adoption and sharing of the kaizen framework as a way to help their clients restructure and refocus their business processes.

History

The small-step work improvement approach was developed in the USA under Training Within Industry program (TWI Job Methods).[16] Instead of encouraging large, radical changes to achieve desired goals, these methods recommended that organizations introduce small improvements, preferably ones that could be implemented on the same day. The major reason was that during WWII there was neither time nor resources for large and innovative changes in the production of war equipment.[17] The essence of the approach came down to improving the use of the existing workforce and technologies.

As part of the aid to allied nations after the war, not directly including the Marshall Plan after World War II, American occupation forces brought in experts to help with the rebuilding of Japanese industry while the Civil Communications Section (CCS) developed a management training program that taught statistical control methods as part of the overall material. Homer Sarasohn and Charles Protzman developed and taught this course in 1949–1950. Sarasohn recommended W. Edwards Deming for further training in statistical methods.

The Economic and Scientific Section (ESS) group was also tasked with improving Japanese management skills and Edgar McVoy was instrumental in bringing Lowell Mellen to Japan to properly install the Training Within Industry (TWI) programs in 1951. The ESS group had a training film to introduce TWI's three "J" programs: Job Instruction, Job Methods and Job Relations. Titled "Improvement in Four Steps" (Kaizen eno Yon Dankai), it thus introduced kaizen to Japan.

For the pioneering, introduction, and implementation of kaizen in Japan, the Emperor of Japan awarded the Order of the Sacred Treasure to Dr. Deming in 1960. Subsequently, the Union of Japanese Scientists and Engineers (JUSE) instituted the annual Deming Prizes for achievement in quality and dependability of products. On October 18, 1989, JUSE awarded the Deming Prize to Florida Power & Light Co. (FPL), based in the US, for its exceptional accomplishments in process and quality-control management, making it the first company outside Japan to win the Deming Prize.[18]

Kaoru Ishikawa took up this concept to define how continuous improvement or kaizen can be applied to processes, as long as all the variables of the process are known.[19]

Implementation

The Toyota Production System is known for kaizen, where all line personnel are expected to stop their moving production line in case of any abnormality, and, along with their supervisor, suggest an improvement to resolve the abnormality which may initiate a kaizen. This feature is called Jidoka or "autonomation".

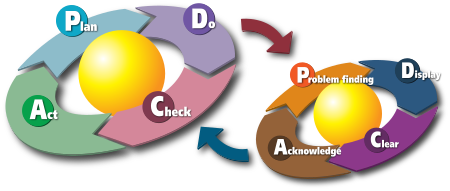

The cycle of kaizen activity can be defined as: Plan → Do → Check → Act. This is also known as the Shewhart cycle, Deming cycle, or PDCA.

Another technique used in conjunction with PDCA is the five whys, which is a form of root cause analysis in which the user asks a series of five "why" questions about a failure that has occurred, basing each subsequent question on the answer to the previous.[21][22] There are normally a series of causes stemming from one root cause,[23] and they can be visualized using fishbone diagrams or tables. The five whys can be used as a foundational tool in personal improvement.[24]

Masaaki Imai made the term famous in his book Kaizen: The Key to Japan's Competitive Success.[1]

In the Toyota Way Fieldbook, Liker and Meier discuss the kaizen blitz and kaizen burst (or kaizen event) approaches to continuous improvement. A kaizen blitz, or rapid improvement, is a focused activity on a particular process or activity. The basic concept is to identify and quickly remove waste. Another approach is that of the kaizen burst, a specific kaizen activity on a particular process in the value stream.[25]

In the 1990s, Professor Iwao Kobayashi published his book 20 Keys to Workplace Improvement and created a practical, step-by-step improvement framework called "the 20 Keys". He identified 20 operations focus areas which should be improved to attain holistic and sustainable change. He went further and identified the five levels of implementation for each of these 20 focus areas. Four of the focus areas are called Foundation Keys. According to the 20 Keys, these foundation keys should be launched ahead of the others in order to form a strong constitution in the company. The four foundation keys are:

- Key 1 – Cleaning and Organizing to Make Work Easy, which is based on the 5S methodology.

- Key 2 – Goal Alignment/Rationalizing the System

- Key 3 – Small Group Activities

- Key 4 – Leading and Site Technology

See also

- Business process re-engineering

- Desensitization (psychology)

- Experiential learning

- Hansei

- Kaikaku

- Kanban, Kanban Method

- Management fad

- Mottainai, a sense of regret concerning waste

- Muda (Japanese term)

- Overall equipment effectiveness

- Quality circle

- Six Sigma

- Statistical process control

- Theory of constraints

- Total productive maintenance

- Transitional living

- TRIZ, the theory of inventive problem solving

- Visual control

- Ikigai

- BADIR

References

- ^ a b Imai, Masaaki (1986). Kaizen: The Key to Japan's Competitive Success. New York: Random House.

- ^ Furterer, Sandra L.; Wood, Douglas C. (25 January 2021). The ASQ Certified Manager of Quality/Organizational Excellence Handbook. Quality Press. p. 344. ISBN 978-1-951058-07-4. Retrieved 18 June 2024.

- ^ Europe Japan Centre, Kaizen Strategies for Improving Team Performance, Ed. Michael Colenso, London: Pearson Education Limited, 2000

- ^ "A never-ending journey of kaizen". 5 July 2020.

- ^ "Opinion: How Toyota strayed from the quality-control path and lost its way". The Globe and Mail. 16 March 2010.

- ^ "Debunked: "kaizen = Japanese philosophy of continuous improvement"". Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 15 August 2009.

- ^ Clary, Scott Douglas (27 July 2019). "Kaizen, Mastering Eastern Business Philosophy". ROI Overload. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ^ "W-questions: Worksheet". Lehrerfreund.de. 11 April 2015. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ Hagen, Stefan (28 December 2006). "6 W-questions". Project management blog. Pm-Blog.com. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ Nickel, Peter. "Work analysis, evaluation and design (Lecture)" (PDF). Uni-Oldenburg.de. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ Tozawa, Bunji; Japan Human Relations Association (1995). The improvement engine: creativity & innovation through employee involvement: the Kaizen teian system. Productivity Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-56327-010-9. Retrieved 6 February 2010.

- ^ Laraia, Anthony C.; Patricia E. Moody; Robert W. Hall (1999). The Kaizen Blitz: accelerating breakthroughs in productivity and performance. John Wiley and Sons. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-471-24648-0. Retrieved 6 February 2010.

- ^ "Five Reasons to Implement Kaizen in Non-Manufacturing". 6sigma.us. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ^ Hamel, Mark (2010). Kaizen Event Fieldbook: Foundation, Framework, and Standard Work for Effective Events. Society Of Manufacturing Engineers. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-87263-863-1. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ^ Karen Martin; Mike Osterling (5 October 2007). The Kaizen Event Planner. Productivity Press. p. 240. ISBN 978-1563273513.

- ^ Graupp P., Wrona B. (2015). The TWI Workbook: Essential Skills for Supervisors. New York: Productivity Press. ISBN 9781498703963.

- ^ Misiurek, Bartosz (2016). Standardized Work with TWI: Eliminating Human Errors in Production and Service Processes. New York: Productivity Press. ISBN 9781498737548.

- ^ US National Archives – SCAP collection – PR News Wire[citation needed]

- ^ Balay, Reza Sadigh (2013). Hacia la excelencia: sector del mueble y afines. Editorial Club Universitario. p. 33. ISBN 978-8484549598.

- ^ "Taking the First Step with PDCA". 2 February 2009. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ 5 Whys

- ^ "Determine the Root Cause:5 Whys". 26 February 2010. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- ^ "An Introduction to 5-Why". 2 April 2009. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- ^ "The 5 Whys and 5 Hows – When Clarity Is Just Two Questions Away". Archived from the original on 14 February 2017. Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- ^ Liker, Jeffrey; Meier, David (2006). The Toyota Way Fieldbook. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Further reading

- Dinero, Donald (2005). Training Within Industry: The Foundation of. Productivity Press. ISBN 1-56327-307-1.

- Bodek, Norman (2010). How to do Kaizen: A new path to innovation - Empowering everyone to be a problem solver. Vancouver, WA, US: PCS Press. ISBN 978-0-9712436-7-5.

- Graban, Mark; Joe, Swartz (2012). Healthcare Kaizen: Engaging Front-Line Staff in Sustainable Continuous Improvements (1 ed.). Productivity Press. ISBN 978-1439872963.

- Maurer, Robert (2012). The Spirit of Kaizen: Creating Lasting Excellence One Small Step at a Time (1 ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0071796170.

- Emiliani, Bob; Stec, David; Grasso, Lawrence; Stodder, James (2007). Better Thinking, Better Results: Case Study and Analysis of an Enterprise-Wide Lean Transformation (2e. ed.). Kensington, CT, US: The CLBM, LLC. ISBN 978-0-9722591-2-5.

- Hanebuth, D. (2002). Rethinking Kaizen: An empirical approach to the employee perspective. In J. Felfe (Ed.), Organizational Development and Leadership (Vol. 11, pp. 59-85). Frankfurt a. M.: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3-631-38624-8.

- Imai, Masaaki (1986). Kaizen: The Key to Japan's Competitive Success. McGraw-Hill/Irwin. ISBN 0-07-554332-X.

- Imai, Masaaki (1 March 1997). Gemba Kaizen: A Commonsense, Low-Cost Approach to Management (1e. ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-031446-2.

- Scotchmer, Andrew (2008). 5S Kaizen in 90 Minutes. Management Books 2000 Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85252-547-7.

- Kobayashi, Iwao (1995). 20 Keys to Workplace Improvement. Portland, OR, USA: Productivity, Inc. ISBN 1-56327-109-5.