John Newbery

John Newbery | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 9 July 1713 Waltham St Lawrence, Berkshire, England |

| Died | 22 December 1767 (aged 54) London, England |

| Resting place | Waltham Saint Lawrence |

| Occupation | Publisher |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Children's literature |

| Notable works | The History of Little Goody Two-Shoes |

| Spouse | Jordan Mary Carnan (m. 1739) |

| Children | 6 |

| Relatives | Elizabeth Anne Le Noir (adoptive granddaughter) |

John Newbery (9 July 1713 – 22 December 1767), considered "The Father of Children's Literature", was an English publisher of books who first made children's literature a sustainable and profitable part of the literary market.[1] He also supported and published the works of Christopher Smart, Oliver Goldsmith and Samuel Johnson. In recognition of his achievements the Newbery Medal was named after him in 1922.[2]

Early life

Newbery was born in 1713 to Robert Newbery,[3]: 201 a farmer, in Waltham St Lawrence, Berkshire, England, and an unknown mother. When he was younger he gave himself an education. He was apprenticed to a local printer, William Ayers, at the age of sixteen. The business was later sold to William Carnan. In 1737 Carnan died, leaving the business to his brother, Charles Carnan, and Newbery. Two years later, Newbery married William Carnan's widow, Jordan Mary.[4] He adopted Mary's three children, John, Thomas and Anna-Maria. In 1740 their daughter Mary was born. John, born in 1741, died at age 11. Son Francis arrived in 1743. [3]: 202

Publishing career

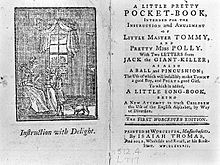

By 1740 Newbery had started his publishing business in Reading. His first two publications were an edition of Richard Allestree's The Whole Duty of Man and Miscellaneous Works Serious and Humerous [sic] In Verse and Prose. In 1743, Newbery left Reading, putting his stepson John Carnan in charge of his business there, and established a shop in London, first at the sign of the Bible and Crown near Devereux Court. He published several adult books, but he became interested in expanding his business to children's books. His first children's book, A Little Pretty Pocket-Book, appeared 18 July 1744.[3]: 201 A Little Pretty Pocket-Book is the first in Newbery's successful line of children's books. The book cost six pence but for an extra two the purchaser received a red and black ball or pincushion.[5] Newbery, like John Locke, believed that play was a better enticement to children's good behaviour than physical discipline,[6] and the child was to record their behaviour by either sticking a pin in the red side for good behaviour or the black side if they were bad. A Little Pretty Pocket-Book, though it would seem didactic today, was well received. Promising to "infallibly make Tommy a good boy and Polly a good girl",[7]: xiv it had poems, proverbs and an alphabet song. The book was child sized with a brightly coloured cover that appealed to children—something new in the publishing industry. Known as gift books, these early books became the precursor to the toy books popular in the nineteenth century.[8] In developing his particular brand of children's literature, Newbery borrowed techniques from other publishers, such as binding his books in Dutch floral paper and advertising his other products and books within the stories he wrote or commissioned.[9] This improvement in the quality of books for children, as well as the diversity of topics he published, helped make Newbery the leading producer of children's books in his time.[7]: xiv

In 1745 Newbery moved his firm to a more upmarket address at 65 St. Paul's Churchyard and named it the Bible and Sun, continuing to publish a mix of adult and children's titles. This new shop did so well he eventually sold the Reading business. His success allowed his son Francis to attend both Cambridge and Oxford Universities.[3]: 202 Jan Susina, writing in The Lion and the Unicorn says "Newbery's genius was in developing the fairly new product category, children's books, through his frequent advertisements ... and his clever ploy of introducing additional titles and products into the body of his children's books."[10]

About one-fifth of the five hundred books Newbery produced were children's stories, including ABC books, children's novels and children's magazines.[4] He published his own books as well as those by authors like Samuel Johnson and Oliver Goldsmith. Scholars have speculated that Goldsmith[11]: 36 or Giles and Griffith Jones[12] wrote The History of Little Goody Two-Shoes, Newbery's most popular book. It had 29 editions between 1765 and 1800.[12] Some sources credit Newbery with publishing the first edition of Mother Goose in England,[13] but others now say the book may have been planned, but was never actually produced.[14] Newbery also published a series of books written by "Tom Telescope" that were wildly popular, going through seven editions between 1761 and 1787 alone.[12] These were based on the emerging science of the day and consisted of a series of lectures given by a boy, Tom Telescope. The most famous is The Newtonian System of Philosophy Adapted to the Capacities of Young Gentlemen and Ladies.

John Newbery died 22 December 1767, at his house in St. Paul's Churchyard.[15] He is buried in his birthplace of Waltham Saint Lawrence.[3]: 203

Patent medicine

Newbery's prosperity did not just come from publishing; he was one of the most successful merchants in England at the time.[16] Some of his fortunes came from the patent and sales of Dr Robert James's Fever Powder, a medicine which claimed to cure gout, rheumatism, scrofula, scurvy, leprosy, and distemper in cattle.[4] This product became successful due in part to Newbery's advertisements for it in his literature. In Goody Two-Shoes, the heroine's father dies because he was "seized with a violent fever in a place where Dr. James Fever Powder was not to be had."[17]

Newbery used his fortune to help writers through financial difficulties. Those he is known to have assisted include Johnson, who called him "Jack Whirler" for his constant activity and inability to sit still; and Goldsmith, who portrayed Newbery in The Vicar of Wakefield as Dr Primrose, "the friend of all mankind".[7]: xiv

Newbery's themes

Locke had written that "children may be cozened [tricked] into a knowledge of the letters; be taught to read, without perceiving it to be anything but a sport, and play themselves into that which others are whipped for." He also suggested that picture books be created for children. Locke also argued that children should be considered "reasoning beings." Newbery acted upon these suggestions. A Pretty Little Pocket-Book was a hodge-podge of information and games, including riddles and advice on a proper diet, but its primary message was "learn your lessons ... and one day you will ride in a coach and six."[12] "In Newbery's universe work is always rewarded and altruism pays dividends as reliably as Isaac Newton's laws of motion."[12]

Newbery's tales seem didactic today, but were popular and enjoyed by children of the 18th and 19th centuries. They draw the world as a meritocracy where a child rises or falls on his or her character. Most of his stories concern a virtuous orphan who works hard (or is "industrious"), and therefore eventually becomes prosperous. They tell the life of the orphan from childhood to adulthood, to illustrate rewards and punishments associated with "good" and "bad" behaviour.

Legacy

His son Francis, his stepson Thomas Carnan, his nephew Francis and Francis's wife Elizabeth and his grandson Francis Power continued the business after his death, though with less cooperation than John Newbery had anticipated; the son and stepson frequently differentiated themselves from the nephew through their imprints, and had a less than cordial relationship between each other as well. Francis (nephew) struck out on his own without legally inheriting any of John Newbery's publications, only a share of his newspaper interests. Nevertheless, he persevered, and upon his death in 1780, his widow Elizabeth inherited the firm through his will. Elizabeth carried on a successful, independent twenty-two year career, retiring in 1802 by selling the business to her successor, John Harris.

In 1922, the John Newbery Medal was created by the American Library Association in his honour; it is awarded each year to the "most distinguished contribution to American literature for children".[18]

Bestselling Newbery books

According to the New Cambridge Bibliography of English Literature (NCBEL 2.120), Newbery "wrote, wholly or partly" and "edited or materially influenced" the following works:

- Mother Goose's Melody[13]

- A Little Pretty Pocket-Book (1744) by M. F. Thwaite and John Newbery

- The Newtonian System of Philosophy (1761) by Tom Telescope, John Newbery, and Oliver Goldsmith

- The Renowned History of Giles Gingerbread (1764)

- The History of Little Goody Two-Shoes (1765) by John Newbery (perhaps written with Oliver Goldsmith)

- The entertaining history of Tommy Gingerbread: a little boy, who lived upon learning[19]

References

- ^ Matthew O Grenby (2013). "Little Goody Two-Shoes and Other Stories: Originally Published by John Newbery". p. vii. Palgrave Macmillan

- ^ Maxted, Ian. "John Newbery". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2 January 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Marks, Diana F. (2006). Children's book award handbook. Westport, Conn: Libraries Unlimited.

- ^ a b c Rose, p. 216.

- ^ Townsend, John Rowe. Written for Children. (1976). London: Pelican, p. 31 and The Oxford Companion to Children's Literature (1984). Oxford: O.U.P. ISBN 0-19-211582-0, p. 375.

- ^ Townsend, John Rowe. Written for Children. (1990). New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-446125-4, pp. 15–16.

- ^ a b c Gillespie, John Thomas (2001). The Newbery Companion: Booktalk and Related Materials for Newbery Medal and Honor Books. Libraries Unlimited. ISBN 9781563088131.

- ^ Lundin, Anne H. (1994). "Victorian Horizons: The Reception of Children's Books in England and America, 1880–1900". The Library Quarterly. 64. The University of Chicago Press: 30–59. doi:10.1086/602651. S2CID 143693178.

- ^ Rose, p. 218.

- ^ Susina, Jan (June 1993). "Editor's Note: Kiddie Lit(e): The Dumbing Down of Children's Literature". The Lion and the Unicorn. 17 (1): v–vi. doi:10.1353/uni.0.0256. S2CID 144833564.

- ^ Arbuthnot, May Hill (1964). Children and Books. Scott, Foresman.

- ^ a b c d e Rose, p. 219.

- ^ a b "Mother Goose's melody : Prideaux, William Francis, 1840-1914 : Free Download & Streaming : Internet Archive". Internet Archive. 1904.

- ^ Barchilon, Jacques (1960). The authentic Mother Goose fairy tales and nursery rhymes. Denver: A. Swallow. p. 11.

- ^ Welsh, Charles (1894). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 40. pp. 312–314.

- ^ Buck, John Dawson Carl (1997). "The Motives of Puffing: John Newbery's Advertisements 1742–1767". Studies in Bibliography. 30: 196–210. JSTOR 40371663.

- ^ Quoted in Rose, p. 219.

- ^ "Newbery Awards". Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- ^ Oliver Goldsmith; Griffith Jones; John Newbery (2 August 2010). The entertaining history of Tommy Gingerbread: a little boy, who lived upon learning. Nabu Press. ISBN 978-1176697331.

Further reading

- Darton, F. J. Harvey. Children's Books in England. 3rd ed. Rev. Brian Alderson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

- Grey, Jill E (1970). "The Lilliputian Magazine – A Pioneering Periodical?". Journal of Librarianship. 2 (2): 107–115. doi:10.1177/096100067000200203. S2CID 58395397.

- Granahan, Shirley. "John Newbery: Father of Children's Literature". ABDO Publishing, 2010.

- Jackson, Mary V. Engines of Instruction, Mischief, and Magic: Children's Literature in England from Its Beginnings to 1839. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1989.

- Maxted, Ian. "John Newbery"[permanent dead link]. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 22 April 2007.

- Noblett, William (1972). "John Newbery: Publisher Extraordinary". History Today. 22: 265–271.

- Roscoe, S. John Newbery and His Successors 1740–1814: a Bibliography. Wormley: Five Owls Press Ltd., 1973.

- Rose, Jonathan. "John Newbery". The British Literary Book Trade, 1700–1820. Eds. J. K. Bracken and J. Silver. Dictionary of Literary Biography. Vol. 154. 1995.

- Townsend, John Rowe. John Newbery and His Books: Trade and Plumb-cake for ever, huzza! Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 1994.

- Welsh, Charles. A Bookseller of the Last Century, being Some Account of the Life of John Newbery. First published in 1885. Clifton, N.J.: Augustus M. Kelley, 1972. ISBN 0-678-00883-3.

External links

Media related to John Newbery at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to John Newbery at Wikimedia Commons- Historical survey of children's literature Archived 11 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine in the British Library