Ithaca (island)

Native name: Ιθάκη | |

|---|---|

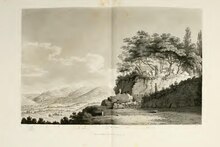

View of Vathy | |

Ithaca within the Ionian Islands | |

| Geography | |

| Coordinates | 38°22′N 20°43′E / 38.367°N 20.717°E |

| Archipelago | Ionian Islands |

| Area | 117.8 km2 (45.5 sq mi) |

| Administration | |

| Region | Ionian Islands |

| Regional unit and municipality | Ithaca |

| Largest settlement | Vathy |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 2,862 (2021) |

| Pop. density | 24/km2 (62/sq mi) |

| Additional information | |

| Official website | www |

Ithaca, Ithaki or Ithaka (/ˈɪθəkə/; Greek: Ιθάκη, Ithaki [iˈθaci]; Ancient Greek: Ἰθάκη, Ithákē [i.tʰá.kɛː]) is a Greek island located in the Ionian Sea, off the northeast coast of Kefalonia and to the west of continental Greece.

Ithaca's main island has an area of 96 square kilometres (37 sq mi) and in 2021 had a population of 2,862. It is the second-smallest of the seven main Ionian Islands, after Paxi. Ithaca is a separate regional unit of the Ionian Islands region, and the only municipality of the regional unit. The capital is Vathy (or Vathi).[1][2]

Modern Ithaca is generally identified with Homer's Ithaca, the home of Odysseus, whose delayed return to the island is the plot of the epic poem Odyssey.

Alternative names

Although the name Ithaca or Ithaka has remained unchanged since ancient times, written documents of different periods also refer to the island by other names, such as:

- Val di Compare (Valley of the Bestman), Piccola (Small) Cephallonia, Anticephallonia (Middle Ages until the beginning of the Venetian period)

- Ithaki nisos (Greek for island), Thrakoniso, Thakou, Thiakou (Byzantine period)

- Thiaki (Byzantine and before the Venetian period)

- Teaki (Venetian period)

- Fiaki (Ottoman period)

History

The island has been inhabited since the 4th millennium BC. It may have been the capital of Cephalonia during the Mycenaean period and the capital-state of the small kingdom ruled by Odysseus. The Romans occupied the island in the 2nd century BC, and later it became part of the Byzantine Empire. The Normans ruled Ithaca in the 13th century, and after a short Turkish rule it fell into Venetian hands (Ionian Islands under Venetian rule).

Ithaca was subsequently occupied by France under the 1797 Treaty of Campo Formio. It was liberated by a joint Russo-Turkish force commanded by admirals Fyodor Ushakov and Kadir Bey in 1798 and subsequently became a part of the Septinsular Republic, which was originally established as a protectorate of the Russian Empire and Ottoman Empire. It became a French possession again in 1807, until it was taken over by the United Kingdom in 1809. Under the 1815 Treaty of Paris, Ithaca became a state of the United States of the Ionian Islands, a protectorate of the British Empire. In 1830, the local community requested to join with the rest of the newly restored nation-state of Greece. Under the 1864 Treaty of London, Ithaca, along with the remaining six Ionian islands, was ceded to Greece as a gesture of diplomatic friendship to Greece's new Anglophile king, George I. The United Kingdom kept its privileged use of the harbour at Corfu.[3]

First settlers

The origins of the first people to inhabit the island, which occurred during the last years of the Neolithic period (4000–3000 BC), are not clear. The traces of buildings, walls and a road from this time period prove that life existed and continued to do so during the Early Helladic era (3000–2000 BC). In the years (2000–1500 BC), some of the population migrated to part of the island. The buildings and walls that were excavated showed the lifestyle of this period had remained primitive.

Mycenaean era

During the Mycenaean period (1600–1100 BC), Ithaca rose to the highest level of its ancient history.[4] Mostly based on the Odyssey and oral traditions, it is believed that the island became the capital of the Ionian Kingdom-State, which included the surrounding lands, and was referred to as one of the most powerful states of that time. The Ithacans were characterized as great navigators and explorers with daring expeditions reaching further than the Mediterranean Sea.

The epic poems of Homer, the Iliad and the Odyssey, shed some light on Bronze-Age Ithaca. Those poems are generally thought to have been composed sometime in the 9th or 8th centuries BC, but may have made use of older mythological and poetic traditions; their depiction of the hero Odysseus and his rule over Ithaca and the surrounding islands and mainland preserves some memories of the political geography, customs, and society of the time.

After the end of the Mycenaean period Ithaca's influence diminished, and it came under the jurisdiction of the nearest large island.

Hellenistic era

During the ancient Hellenic prime (800–180 BC), independent organized life continued in the northern and southern part of the island. In the southern part, in the area of Aetos, the town Alalcomenae was founded. From this period, many objects of important historical value have been found during excavations. Among these objects are coins imprinted with the name Ithaca and the image of Odysseus which suggest that the island was self-governed.

Middle Ages

Across time, the island fell to various conquerors and experienced changed circumstances, meaning the population of the island kept changing through history. Although there is no definite numerical information until the Venetian period, it is believed that from the Mycenaean to the Byzantine period, the number of inhabitants was several thousand, who lived mainly in the northern part of Ithaca. During the Middle Ages, the population decreased due to the continuous invasions of pirates, forcing the people to establish settlements and live in the mountains.

The island, often referred to with the name 'Val di Compare', followed the fortunes of its bigger neighbor Cephalonia throughout the 12th and 13th centuries, when it formed part of the holdings of various Latin rulers. In 1185, when Cephalonia and Zakynthos were captured by Margaritone of Brindisi, it is most likely that Ithaca was among the territory he conquered.[5] Later, Ithaca changed ownership together with Cephalonia, first to the Orsini family after Margaritone's death, and then to John of Gravina, prince of Achaia, who conquered them from the Orsini in 1324.[5] From 1333 until 1357 the islands were transferred to Robert of Taranto, who in 1357, bestowed them upon Leonardo Tocco, a Neapolitan courtier.[5] While Ithaca had until now merely followed the fate of Cephalonia, it is under the Tocco that more specific mentions of Ithaca begin to appear in the record. In the 15th century, there was one family, the Galati, with noble privileges and land interests on the island given by the Tocco family.[5]

Ottoman and Venetian eras

In 1479, Ottoman forces reached the islands and many of the people fled from the island out of fear of the new Turkish settlers.[5] Those who remained hid in the mountains to avoid the pirates who controlled the channel between Cephalonia and Ithaca and the bays of the island. In the following five years, the Turks, Tocco and Venetians laid claim to the islands diplomatically. Possession of the islands was finally taken by the Ottoman Empire from 1484 to 1499. During this period, the Venetians had strengthened into a major power with an organized fleet. The Venetians pursued their interest in the Ionian Islands, and in 1499 a war between the Venetians and the Turks began. The allied fleets of the Venetians and the Spanish besieged Ithaca, and the other islands. The fleets prevailed, and from 1500 onwards the Venetians controlled the islands. According to a treaty of 1503, Ithaca, Cephalonia and Zakynthos would be ruled by the Venetians, and Lefkada by the Ottoman Empire. By then Ithaca was almost uninhabited, and the Venetians had to grant incentives to settlers from neighbouring islands and the mainland to repopulate it.[4] 1504, the Venetians ordered official the repopulation of Ithaca with tax incentives to attract settlers from neighbouring islands. The Venetian authorities found the island was already being repopulated by members of the Galatis family, who laid claim to it as their property, having received rights over Ithaca under the Tocco regime.[6] However, according to historians, the island received a great population revival in the period before and after the fall of Candia when numerous people from Crete arrived there as well as the noble Karavia family (Latin: Caravia), a branch of the ancient byzantine Kallergi family. This family and its followers inhabited settlements on the island, received fiefs from the Venetian Senate and indulged in a tremendously profitable maritime trade as well as piracy against the Ottomans. According to the French traveler Leake during the 18th century the families of Karavias, Petalas and the Dendrinos constituted the three main factions of the island, with the Karavias controlling its most productive part. During the next centuries the island remained under Venetian control.[7]

French era

A few years after the French Revolution, the Ionian area came under the rule of the First French Republic (1797–1798), and the island became the honorary capital of the French département of Ithaque, comprising Cephalonia, Lefkada, and part of the mainland (the prefecture was at Argostoli on Kefalonia).

The population welcomed the French, who took care in the control of the administrative and judicial systems, but later the heavy taxation they demanded caused a feeling of indignation among the people. During this short historical period, the new ideas of system and social structure greatly influenced the inhabitants of the island. At the end of 1798, the French were succeeded by Russia and Turkey (1798–1807), which were allies at that time. Corfu became the capital of the Septinsular Republic, and the form of government was democratic, with a fourteen-member senate in which Ithaca had one representative.

The Ithacan fleet flourished when it was allowed to carry cargo up to the ports of the Black Sea. In 1807, according to the Tilsit Treaty with Turkey, the Ionian Islands once again came under the French rule (1807–1809 AD). The French quickly began preparing to face the British fleet, which had become very powerful, by building a fort in Vathy.

British and modern eras

In 1809 Great Britain mounted a blockade on the Ionian Islands as part of the war against Napoleon, and in September of that year they hoisted the British flag above the castle of Zakynthos. Cephalonia and Ithaca soon surrendered, and the British installed provisional governments. The Treaty of Paris (1815) recognised the United States of the Ionian Islands and decreed that it become a British protectorate. Colonel Charles Philippe de Bosset became provisional governor between 1810 and 1814.[8]

A few years later Greek nationalist groups started to form. Although their energy in the early years was directed to supporting their fellow Greek revolutionaries in the revolution against the Ottoman Empire, they switched their focus to enosis with Greece following their independence. The Party of Radicals (Greek: Κόμμα των Ριζοσπαστών) founded in 1848 as a pro-enosis political party. In September 1848, there were skirmishes with the British garrison in Argostoli and Lixouri on Kefalonia, which led to a certain level relaxation in the enforcement of the protectorates laws, and freedom of the press as well. The island's populace did not hide their growing demands for enosis, and newspapers on the islands frequently published articles criticising British policies in the protectorate. On the 15th of August in 1849, another rebellion broke out, which was quashed by Henry George Ward, who proceeded to temporarily impose martial law.[9]

During the British protectorate period prominent citizens of Ithaki participated in the secret "Philiki Etairia" which was instrumental in organizing the Greek Revolution of 1821 against Turkish rule, and Greek fighters found refuge there. In addition, the participation of Ithacans during the siege of Messolongi and the naval battles against Ottoman ships on the Black Sea and the Danube was significant.[citation needed]

Ithaca was annexed to the Greek Kingdom with the rest of the Ionian islands in 1864.[3]

Home of Odysseus

Since antiquity, Ithaca has been identified as the home of the mythological hero Odysseus. In the Odyssey of Homer, Ithaca is described thus

...dwell in clear-seen Ithaca, wherein is a mountain, Neriton, covered with waving forests, conspicuous from afar; and round it lie many isles hard by one another, Dulichium, and Same, and wooded Zacynthus. Ithaca itself lies close in to the mainland the furthest toward the gloom, but the others lie apart toward the Dawn and the sun—a rugged isle, but a good nurse of young men[10]

It has sometimes been argued that this description does not match the topography of modern Ithaca. Three features of the description have been seen as especially problematic. First, Ithaca is described as "low-lying" (χθαμαλή), but Ithaca is mountainous. Second, the words "farthest out to sea, towards the sunset" (πανυπερτάτη εἰν ἁλὶ ... πρὸς ζόφον) are usually interpreted to mean that Ithaca must be the island furthest to the west, but Kefalonia lies to the west of Ithaca. Lastly, it is unclear which modern islands correspond to Homer's Doulichion and Same.[4]

The Greek geographer Strabo, writing in the 1st century AD, identified Homer's Ithaca with modern Ithaca. Following earlier commentators, he interpreted the word translated above as "low-lying" to mean "close to the mainland", and the phrase translated as "farthest out to sea, towards the sunset" as meaning "farthest of all towards the north." Strabo identified Same as modern Kefalonia, and believed that Homer's Doulichion was one of the islands now known as the Echinades. Ithaca lies farther north than Kefalonia, Zacynthos, and the island that Strabo identified as Doulichion, consistent with the interpretation of Ithaca as being "farthest of all towards the north."

Strabo's explanation has not won universal acceptance. In the last few centuries, some scholars have argued that Homer's Ithaca was not modern Ithaca, but a different island.[11] Perhaps the best known proposal is that of Wilhelm Dörpfeld, who believed that the nearby island of Lefkada was Homer's Ithaca, whereas Same was the present-day Ithaca.[12][13]

It has also been suggested that Paliki, the western peninsula of Kefalonia, is Homer's Ithaca. It has been argued that in Homeric times Paliki was separated from Kefalonia by a sea channel since closed up by earthquake-induced rockfalls.[14] However, no scientific review publications are available in support of this theory.[11] Indeed, scholars have found that "all the geological and geomorphological evidence refutes this hypothesis".[15]

Despite any difficulties with Homer's description of the island, in classical and Roman times the island now called "Ithaca" was universally held to be the home of Odysseus; the Hellenistic identifications of Homeric sites, such as the identifications of Lipari as the island of Aeolus, are usually taken with a grain of salt, and attributed to the ancient tourist trade.

The island has been known as Ithaca from an early date, as coins and inscriptions show. Coins from Ithaca frequently portray Odysseus, and an inscription from the 3rd century BC refers to a local hero-shrine of Odysseus and games called the Odysseia.[16] The Archaeological site of "School of Homer" on modern Ithaca is the only place in the Lefkas–Kefalonia–Ithaca Triangle where Linear B inscriptions may have been found,[17] near royal remains. In 2010, Greek archaeologists discovered the remains of an 8th-century BC palace in the area of Agios Athanasios, leading to reports that this might have been the site of Odysseus's palace.[18][19]

Another archaeological feature on Ithaca is the so-called Polis Cave near Stavros in the north of the island. Heinrich Schliemann identified it as the cave that Odysseus visited on his return. Sylvia Benton, who carried out research in the cave in the 1930s, also interpreted her findings as an indication of a connection to Odysseus. However, as is now known, the site served as a place of worship for many centuries, from the beginning of the Bronze Age (Early Helladic) to the Roman period, without any clear connection to a possible life environment of Odysseus. Numerous votive offerings indicate that the nymphs in particular were the target of the ritual acts in the Polis cave.[20]

Modern scholars generally accept the identification of modern Ithaca with Homeric Ithaca,[21] and explain discrepancies between the Odyssey's description and the actual topography as the product of lack of first-hand knowledge of the island, or as poetic licence.[22]

Geography

Ithaca lies east of the northeast coast of Cephalonia, from which it is separated by the Strait of Ithaca. The regional unit covers an area of 117.812 square kilometres (45.5 sq mi)[23] and has approximately 100 kilometres (62 miles) of coastline. The main island stretches in the north-south direction, in length of 23 km (14 miles) and maximum width of 6 km (4 miles). It consists of two parts, of about equal size, connected by the narrow isthmus of Aetos (Eagle), just 600 metres (1,969 feet) wide. The two parts enclose the bay of Molos, whose southern branch is the harbor of Vathy, the capital and largest settlement of the island. The second largest village is Stavros in the northern part.[24]

Lazaretto Islet (or Island of The Saviour) guards the harbor. The church of The Saviour and the remains of an old gaol are located on the islet.[25]

The capes in the island include Exogi, the westernmost, Melissa to the north, Mavronos, Agios Ilias, Schinous, Sarakiniko and Agios Ioannis, to the east, and Agiou Andreou, to the south. Bays include Afales Bay to the northwest, Frikes and Kioni Bays to the northeast, Molos Gulf to the east, and Ormos Gulf and Sarakiniko Bay to the southeast. The tallest mountain is Nirito in the northern part (806 m), followed by Merovigli (669 m) in the south.

Administration

The island Ithaca is part of the regional unit Ithaca, which is part of the Ionian Islands region. The only municipality of this regional unit is Ithaca.[26] Ithaca is the only populated island in this municipality, which contains several other islets.

Communities and villages

Aetos, Afales, Agios Ioannis, Agia Saranta, Anogi, Exogi, Frikes, Kalivia, Kathara, Kioni, Kolieri, Lachos, Lefki, Marmaka, Perachori, Piso Aetos, Platrithia, Rachi, Stavros, and Vathy.

Notable people

- Odysseus (13th century BC), legendary Greek king of Ithaca and the hero of Homer's epic poem the Odyssey

- St. Joachim Papoulakis (1786–1868), Athonite monk and an Orthodox Saint

- Nikolaos Galatis (1792-1819) pre-revolutionary figure and member of the Filiki Eteria

- Odysseas Androutsos (1788–1825), fighter in the Greek War of Independence

- Dionysius Rodotheatos (1849-1892), composer

- Platon Drakoulis (1858–1934), philosopher, writer, politician

- Lorentzos Mavilis (1860–1912), poet

- Ioannis Metaxas (1871–1941), general and dictator of Greece. His family descended from Cephalonia.

- Panagis Lekatsas (1911–1970), writer, journalist

- Evgenios Karavias (1752 - 1821) Eminent cleric, Scholar, Metropolitan Bishop of Anchialos, National Martyr and Saint

- Vasilios Karavias (1733 - 1830) Militaryman, one of the pioneers of the Greek revolution in Moldo-Wallachia in 1821

- Karavias Ippokrates (1866 - 1954) Lawyer, journalist and writer. President of Parnassos Philological Association

- Karavias Dimitrios (Misolitros) Fighter of the 1821 Greek Revolution against the Ottomans in Western Greece

See also

References

Citations

- ^ "Vathi, Ithaca". National Gallery Scotland. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- ^ "Port Vathi". Ithacan Philanthropic Society. 2015. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- ^ a b Bourchier, James David (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 729.

- ^ a b c "Ithaca". Encyclopædia Britannica. 16 July 2010. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Miller, William (2015). Essays on the Latin Orient. Cambridge University Press. pp. 261–5. ISBN 978-1-107-45553-5. OCLC 889642379.

- ^ Zapanti, Stamatoula (1998). "Η Ιθάκη στα πρώτα χρόνια τησ Βενετοκρατίας (1500-1571)". Κεφαλληνιακά Χρονικά. 7: 129–133.

- ^ Leake, William Martin (1835). Travels in northern Greece. Vol. 3. London: J. Rodwell. pp. 28–29.

- ^ British Museum. "Col Charles Philippe de Bosset".

- ^ "British Occupation". Archived from the original on 2021-05-06. Retrieved 2020-12-19.

- ^ Homer (1919). "9.21–27". The Odyssey with an English Translation (in Ancient Greek and English). Translated by Murray, Augustus Taber. London, UK: William Heinemann, Ltd. Retrieved 2016-06-06 – via Perseus Digital Library.

- ^ a b Squires, Nick (24 August 2010). "Greeks 'discover Odysseus' palace in Ithaca, proving Homer's hero was real'". The Telegraph. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- ^ Wilhelm Dörpfeld, Alt-Ithaka (1927).

- ^ Map of Homer's Ithaka, Same and Asteris according to Wilhelm Dörpfeld. Digital library of Heidelberg University.

- ^ Bittlestone, Robert; Diggle, James; Underhill, John (2005), Odysseus unbound: the search for Homer's Ithaca, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-85357-6

- ^ Kalliopi Gaki-Papanastassiou, Hampik Maroukian, Efthymios Karymbalis, and Dimitris Papanastassiou, “Geomorphological study and paleogeographic evolution of NW Kefalonia Island, Greece, concerning the hypothesis of a possible location of the Homeric Ithaca,” in Geoarchaeology, Climate Change, and Sustainability, Geological Society of America, Special Paper 476, 2011, pp. 78-79

- ^ Frank H. Stubbings, "Ithaca", in Wace and Stubbings, eds., A Companion to Homer (New York, 1962).

- ^ Litsa Kontorli-Papadopoulou, Thanasis Papadopoulos, Gareth Owens, “A possible Linear sign from Ithaki (AB09 ‘SE’)?” Kadmos, Band 44 (2005), pp. 183-186

- ^ Squires, Nick (24 August 2010). "Greeks 'discover Odysseus' palace in Ithaca, proving Homer's hero was real'". Retrieved 27 March 2018 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ "Greek archaelogists discover Odysseus' palace in Ithaca – GreekReporter.com". greece.greekreporter.com. 25 August 2010. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ^ Deoudi, Maria (2008). Ithake: Die Polis-Höhle, Odysseus und die Nymphen [Ithake: The Polis Cave, Odysseus and the Nymphs]. Thessaloniki: University Studio Press, ISBN 978-9-601-21695-9 (see also the review of this work by Jorrit Kelder).

- ^ Jonathan Brown, In search of Homeric Ithaca (Canberra: Parrot Press, 2020). National Library of Australia, Trove

- ^ West, M. L. (2014). The Making of The Odyssey. Oxford University Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-19-871836-9.

- ^ "Population & housing census 2001 (incl. area and average elevation)" (PDF) (in Greek). National Statistical Service of Greece. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-21.

- ^ "Geography of Ithaca". Greeka.com.

- ^ [1] Archived February 6, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "ΦΕΚ A 87/2010, Kallikratis reform law text" (in Greek). Government Gazette.

Bibliography

- Brown, Jonathan. In search of Homeric Ithaca, Canberra, Parrot Press, 2020.

- Dervenn, Claude. Iles de Grèce d'Ithaque à Samothrace, Paris, Impr. auxiliaire; J. de Gigord. (S.M.), 1939. (in French)

- Hetherington, Paul. The Greek Islands: Guide to the Byzantine and Medieval Buildings and their Art, Londres, 2001.

- Le Noan, Gilles. À la recherche d'Ithaque: essai sur la localisation de la patrie d'Ulysse, Quincy-sous-Sénart, Éd. Tremen, 2001. (in French)

- Schliemann, Henry. Ithaque, le Péloponnèse, Troie: recherches archéologiques, Paris, C. Reinwald, 1869. (in French)

Further reading

- Tzakos, Christos I. Ithaca and Homer, The Truth: The Advocacy of the Case. Translator: Geoffrey Cox. Archived from the original on 2007-05-16.

External links

- Official website (Greek)

Town and Harbour of Ithaca. an engraving by J Tingle of a painting by Charles Bentley for Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1837, with a poetical illustration by Letitia Elizabeth Landon that accepts Ithaca as the home of Ulysses: 'The glorious island where Ulysses was the king'.

Town and Harbour of Ithaca. an engraving by J Tingle of a painting by Charles Bentley for Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1837, with a poetical illustration by Letitia Elizabeth Landon that accepts Ithaca as the home of Ulysses: 'The glorious island where Ulysses was the king'.