Italian cruiser Aquila

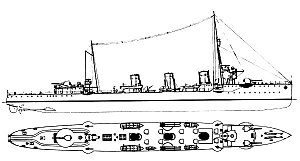

Plan and right elevation line drawing of the Vifor-class destroyers as completed for Italy as scout cruisers. | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Vifor |

| Namesake | Storm |

| Operator | Royal Romanian Navy (planned) |

| Ordered | 1913 |

| Builder | Cantiere Pattison, Naples, Kingdom of Italy |

| Laid down | 11 March 1914 |

| Fate | Requisitioned by Kingdom of Italy 5 June 1915 |

| Name | Aquila |

| Namesake | Eagle |

| Operator | Regia Marina (Royal Navy) |

| Acquired | 5 June 1915 |

| Launched | 26 July 1916 |

| Completed | 8 February 1917 |

| Commissioned | 8 February 1917 |

| Fate |

|

| Reclassified | Destroyer 5 September 1938 |

| Stricken | 6 January 1939 |

| Name | Melilla |

| Namesake | Melilla, a Spanish city on the coast of North Africa |

| Operator |

|

| Acquired |

|

| Stricken | 1950 |

| Fate | Scrapped |

| General characteristics (as built) | |

| Class and type | Vifor-class destroyer |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 94.7 m (310 ft 8 in) (overall) |

| Beam | 9.5 m (31 ft 2 in) |

| Draft | 3.6 m (11 ft 10 in) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | 2 shafts; 2 geared steam turbines |

| Speed | 34 knots (63 km/h; 39 mph) |

| Range | 3,000 nmi (5,600 km; 3,500 mi) at 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph) |

| Complement | 146 |

| Armament |

|

Aquila was an Italian Regia Marina (Royal Navy) scout cruiser in commission from 1917 to 1937. She was laid down for the Royal Romanian Navy as the destroyer Vifor but the Kingdom of Italy requisitioned her while she was under construction. She served in the Regia Marina during World War I, seeing action in the later stages of the Adriatic campaign. In 1928, she took part in rescue operations in the Adriatic Sea for the sunken Italian submarine F 14.

In 1937, Italy transferred her to Nationalist Spain. Reclassified as a destroyer and renamed Melilla, she served in the Spanish Nationalist Navy during the Spanish Civil War and subsequently in the Spanish Navy. She was stricken in 1950 and scrapped.

Design

The Kingdom of Romania ordered the ship as Vifor, the lead ship of a planned 12-ship Vifor class of destroyers for the Royal Romanian Navy envisioned under the Romanian 1912 naval program.[1] Romanian specifications called for the Vifor-class ships to be large destroyers optimized for service in the confined waters of the Black Sea, with a 10-hour endurance at full speed and armed with three 120-millimetre (4.7 in) guns, four 75-millimetre guns, and five torpedo tubes.[2]

After Italy requisitioned the first four Vifor-class ships — the only four of the planned 12 ever constructed — the Italians completed them as scout cruisers to modified designs. Each ship was 94.7 metres (310 ft 8 in) in length overall, with a beam of 9.5 metres (31 ft 2 in) and a draught of 3.6 metres (11 ft 10 in). The power plant consisted of a pair of Tosi steam turbines and five Thornycroft boilers, generating a designed output of 40,000 shaft horsepower (29,828 kW) powering two shafts, which gave each ship a designed top speed of 34 knots (63 km/h; 39 mph), although the ships actually achieved between 35 and 38 knots (65 and 70 km/h; 40 and 44 mph), depending on the vessel. The ships had a range of 1,700 nautical miles (3,150 km; 1,960 mi) at 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph) and 380 nautical miles (700 km; 440 mi) at 34 knots (63 km/h; 39 mph). Each ship had a complement of 146. Armament varied among the ships, and sources disagree on Aquila′s armament when she entered Italian service: According to one source, as completed Aquila had two twin 120-millimetre (4.7 in) guns, two Ansaldo 76-millimetre (3 in) guns, two twin 457-millimetre (18 in) torpedo tubes, and two 6.5-millimetre (0.26 in) machine guns,[2] but other sources claim that she was completed with five 152-millimetre (6 in) and two 76-millimetre (3 in)/40 guns as well as the four torpedo tubes and two machine guns.[3][4][5]

Construction, acquisition, and commissioning

Ordered by the Royal Romanian Navy in 1913,[6] the ship was laid down as Vifor at Cantieri Pattison ("Pattison Shipyard") in Naples, Italy, on 11 March 1914.[5][7] World War I broke out in late July 1914, and Italy entered the war on the side of the Allies on 23 May 1915. Vifor was 60 percent complete when Italy requisitioned her on 5 June 1915[7] for service in the Regia Marina. Renamed Aquila, she was launched on 26 July 1916. She was completed and commissioned on 8 February 1917.[2][5]

Service history

Regia Marina

World War I

1917

After commissioning, Aquila was stationed at Brindisi, Italy.[8] During World War I, she operated in the Adriatic Sea, participating in the Adriatic campaign against Austria-Hungary and the German Empire, taking part primarily in small naval actions involving clashes between torpedo boats and support operations for Allied motor torpedo boat and air attacks on Central Powers forces.[5]

On the night of 14–15 May 1917, the Battle of the Strait of Otranto began when the Austro-Hungarian Navy staged a two-pronged attack against the Otranto Barrage in the Strait of Otranto aimed both at destroying naval drifters — armed fishing boats that patrolled the anti-submarine barrier the barrage formed — and, as a diversionary action, at destroying an Italian convoy bound from the Kingdom of Greece to the Principality of Albania. At 04:10 on 15 May, after receiving news of the attack, Aquila, the protected cruiser Marsala, the scout cruiser Carlo Alberto Racchia, the destroyers Impavido, Indomito, and Insidioso, and the British Royal Navy light cruiser HMS Liverpool made ready for sea at Brindisi. At 05:30 the formation left Brindisi together with the British light cruiser HMS Dartmouth and two other destroyers, joining various Allied naval formations steering to intercept the Austro-Hungarians. At 07:45 the Allied force sighted the Austro-Hungarian destroyers Balaton and Csepel. Aquila and the Italian destroyers steered to attack the two Austro-Hungarian ships at 08:10 and opened fire on them at 08:15. In the ensuing exchange of gunfire, Balaton suffered damage and immediately afterwards Aquila was hit and immobilized at 0905. The Austro-Hungarian scout cruisers Helgoland, Novara, and Saida closed with her. Dartmouth, the British light cruiser HMS Bristol, and the Italian destroyers Antonio Mosto and Giovanni Acerbi placed themselves between Aquila and the Austro-Hungarian ships and opened fire on them at 09:30 at a range of 8,500 metres (9,300 yd). The three Austro-Hungarian ships retreated toward the northwest and the British and Italian ships pursued them at distances of between 4,500 and 10,000 metres (4,900 and 10,900 yd), continuing to fire. The battle ended at 12:05 when the ships approached the major Austro-Hungarian naval base at Cattaro, where the fleeing Austro-Hungarian ships took shelter under the cover of Austro-Hungarian coastal artillery batteries and the Austro-Hungarian armored cruiser Sankt Georg and destroyers Tátra and Warasdiner sortied to intervene in the engagement.[9] After the battle ended, Aquila was towed back to port for repairs.[5]

During the night of 4–5 October 1917, Aquila and Carlo Alberto Racchia provided distant support to an air attack against Cattaro.[10]

An Austro-Hungarian Navy force consisting of Helgoland, Balaton, Csepel, Tátra, and the destroyers Lika, Orjen, and Triglav left Cattaro on 18 October 1917 to attack Italian convoys. The Austro-Hungarians found no convoys, so on on 19 October Helgoland and Lika moved within sight of Brindisi to entice Allied ships into chasing them and lure the Allies into an ambush by the Austro-Hungarian submarines U-32 and U-40. Aquila got underway from Brindisi with Antonio Mosto, Indomito, the scout cruiser Sparviero, the destroyer Giuseppe Missori, the British light cruisers HMS Gloucester and HMS Newcastle, and the French Navy destroyers Bisson, Commandant Bory, and Commandant Rivière to join other Italian ships in pursuit of the Austro-Hungarians, but after a long chase which also saw some Italian air attacks on the Austro-Hungarian ships, the Austro-Hungarians escaped and all the Italian ships returned to port without damage.[8]

On 28 November 1917, an Austro-Hungarian Navy force consisting of Triglav, the destroyers Dikla, Dinara, Huszár, Reka, and Streiter, and the torpedo boats TB 78, TB 79, TB 86, and TB 90 attacked the Italian coast. While Dikla, Huszar, Streiter and the torpedo boats unsuccessfully attacked first Porto Corsini and then Rimini, Dinara, Reka, and Triglav bombarded a railway near the mouth of the Metauro, damaging a train, the railway tracks, and telegraph lines. The Austro-Hungarian ships then reunited and headed back to the main Austro-Hungarian naval base at Pola. Aquila, Giovanni Acerbi, Sparviero, and the destroyers Animoso, Ardente, Ardito, Audace, Francesco Stocco, Giuseppe Cesare Abba, Giuseppe Sirtori, and Vincenzo Giordano Orsini departed Venice, Italy, and, together with reconnaissance seaplanes, pursued the Austro-Hungarian formation. The seaplanes attacked the Austro-Hungarians without success, and the Italian ships had to give up the chase when they did not sight the Austro-Hungarians until they neared Cape Promontore on the southern coast of Istria, as continuing beyond it would bring them too close to Pola.[8]

Aquila and Sparviero escorted a force of destroyers and smaller vessels as they bombarded Central Powers forces in Grisolera, Italy, on 19 December 1917.

1918

On 10 February 1918 Aquila, Ardito, Ardente, Francesco Stocco, Giovanni Acerbi, and Giuseppe Sirtori — and, according to some sources, the motor torpedo boat MAS 18 — steamed to Porto Levante, now a part of Porto Viro, in case they were needed to support an incursion into the harbor at Bakar (known to the Italians as Buccari) by MAS motor torpedo boats. Sources disagree on whether they remained in port or put to sea to operate in distant support,[11] but in any event, their intervention was unnecessary. The motor torpedo boats carried out their raid, which became known in Italy as the Beffa di Buccari ("Bakar mockery").[8]

On 5 September 1918, Aquila, Sparviero, and their sister ship, the scout cruiser Nibbio, put to sea to provide support to the coastal torpedo boats 8 PN and 12 PN. Sources disagree on the purpose of the operation: According to one, the three scout cruisers were tasked to operate about 15 nautical miles (28 km; 17 mi) west of Menders Point while the torpedo boats attacked Austro-Hungarian merchant ships about 15 nautical miles (28 km; 17 mi) to the east at Durrës (known to the Italians as Durazzo) on the coast of Albania,[8] while another claims that they were covering the recovery of a broken-down flying boat that had landed in the Gulf of Drin.[12] In either case, they were to intervene if Austro-Hungarian warships attempted to intercept the torpedo boats. At 12:35, 8 PN spotted three Austro-Hungarian torpedo boats sweeping mines off Ulcinj (known to the Italians as Dulcigno), Albania. The three scout cruisers steered to attack the three Austro-Hungarian ships and opened fire on them, damaging the torpedo boat 86 F and prompting the Austro-Hungarians to retreat toward the coast and take shelter under cover of the Austro-Hungarian coastal artillery at Shëngjin (known to the Italians as San Giovanni de Medua).[8][12]

On 2 October 1918, while other British and Italian ships bombarded Austro-Hungarian positions at Durrës, Aquila, Nibbio, and Sparviero were among numerous ships which operated off Durrës in support of the bomdardment, tasked with countering any attempt by Austro-Hungarian Navy ships based at Cattaro to interfere with the bombardment.[8][12] On 21 October 1918, the three scout cruisers covered a force bombarding Shëngjin.[12]

By late October 1918, Austria-Hungary had effectively disintegrated, and the Armistice of Villa Giusti, signed on 3 November 1918, went into effect on 4 November 1918 and brought hostilities between Austria-Hungary and the Allies to an end. World War I ended a week later with the armistice between the Allies and the German Empire on 11 November 1918. In the war's immediate aftermath, Aquila and Sparviero got underway from Brindisi and took possession of Hvar (known to the Italians as Lesina), an island off the coast of Dalmatia, on 15 November 1918.[13]

Interwar period

According to one source, Aquila′s armament was modified in 1927, when five 152-millimetre (6 in) guns were removed and replaced with four 120-millimetre (4.7 in) guns.[6]

On the morning of 6 August 1928, Aquila got underway from Pola with several other ships for an exercise that also involved the light cruiser Brindisi, steaming from Poreč (known to the Italians as Parenzo) to Pola under escort by the V Destroyer Flotilla. The exercise included a simulated attack on the formation by the submarines F 14 and F 15.[14][15] Shortly after 08:40, the destroyer Giuseppe Missori accidentally rammed F 14, causing F 14 to sink in the Adriatic Sea 7 nautical miles (13 km; 8.1 mi) west of the Brijuni archipelago.[14][15] Aquila was among the first ships to arrive on the scene, and by dragging her anchor chain she helped speed up the identification of the location of the sunken — but largely unflooded —submarine, inside which 23 of the 27 crew members were trapped alive.[14][15] However, the presence of the anchor chain hindered the recovery operations that followed: At 10:15, rescuers began to lift F 14 from the seabed, but Aquila′s anchor chain interfered with the operation by causing the submarine to list.[14][15] The salvage effort had to wait until the 30-ton pontoon GA 145 arrived from Pola and the lifting cable was hooked to GA 145 before F 14 could be freed from the anchor chain and brought to the surface,[14] hours after the surviving crew of F 14 had fallen silent.[14][15] When F 14′s hatches finally were opened, rescuers discovered that her entire crew had died, asphyxiated by carbon dioxide and chlorine gas.[14][15]

Transfer to Spain

On 11 October 1937, during the Spanish Civil War, the government of Fascist Italy handed Aquila over to the navy of the Spanish Nationalists, although the ship officially remained on the rolls of the Regia Marina, which reclassified Aquila as a destroyer on 5 September 1938.[16] The transfer finally became official on 6 January 1939, when the Regia Marina struck Aquila from the navy list.[5][7]

Spanish Navy

Before Fascist Italy transferred Aquila to the Spanish Nationalists, the Nationalists controlled only one non-ex-Italian destroyer, Velasco.[17] Upon taking control of the ship, the Nationalists renamed her Melilla.[5][7] To conceal the transfer, Italy did not make it official, and the Spanish Nationalists took steps to confuse observers as to her identity: They installed a dummy fourth funnel to give her a greater resemblance to the four-funneled Velasco and often referred to her as Velasco-Melilla rather than as Melilla.[17]

By 1937, Melilla was an old ship, so the Spanish Nationalists mainly employed her in surveillance and escort tasks. In August 1938, however, she took part — together with her sister ship Ceuta (formerly the Italian scout cruiser Falco) and the heavy cruiser Canarias — in an action that forced the Spanish Republican Navy destroyer José Luis Díez to give up on running the Nationalist blockade of the Strait of Gibraltar to reach Cartagena and to take refuge at Gibraltar on 29 August instead.[17][18]

Melilla′s transfer to the Spanish Nationalists became official and overt on 6 January 1939 when the Regia Marina struck her from the Italian navy list.[5][7] After the end of the Spanish Civil War in April 1939, the Spanish Navy assigned Melilla to training duties.[18] The Spanish struck her from the navy list in 1950[5] and sold her for scrapping.

References

Citations

- ^ Fraccaroli, p. 421

- ^ a b c Fraccaroli, p. 266

- ^ Warship 1900-1950

- ^ pbworks

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Marina Militare (in Italian).

- ^ a b Pier Paolo Ramoino, Gli esploratori italiani 1919-1938 in Storia Militare, No. 204, September 2010 (in Italian).

- ^ a b c d e "Italian Aquila, Spanish Melilla (Nationalist Navy) - Warships 1900-1950". Warships of World War II (in Czech and English). Archived from the original on 12 April 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g Favre, pp. 193, 197, 202, 204, 222, 253, 255, 271..

- ^ Favre, pp. 115, 140, 145–147, 156, 160, 172, 195, 197, 201, 202.

- ^ Favre, p. 197.

- ^ La Grande Guerra Archived 4 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d Cernuschi & O'Hara, pp. 69, 73.

- ^ Renato Battista La Racine, "In Adriatico subito dopo la vittoria" in Storia Militare, No. 210, March 2011 (in Italian).

- ^ a b c d e f g Tragedia dell'F14 (in Italian).

- ^ a b c d e f Giorgio Giorgerini, Uomini sul fondo. Storia del sommergibilismo italiano dalle origini a oggi, pp. 109–111 (in Italian).

- ^ Esploratori e Navigatori (in Italian).

- ^ a b c Buques de la Guerra Civil Española (1936-1939) - Destructores (in Spanish).

- ^ a b La flota italiana de Franco (in Italian).

Bibliography

- Cernuschi, Enrico & O'Hara, Vincent (2016). "The Naval War in the Adriatic, Part 2: 1917–1918". In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2016. London: Conway. ISBN 978-1-84486-326-6.

- Favre, Franco. La Marina nella Grande Guerra. Le operazioni navali, aeree, subacquee e terrestri in Adriatico (in Italian).

- Fraccaroli, Aldo (1985). "Italy". In Gray, Randal (ed.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. pp. 252–290. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8.

External links

- Photo of Aquila sometime between 1917 and 1919, at Italian Wikipedia