Isabella II

| Isabella II | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

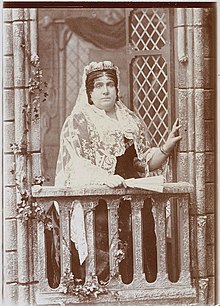

Formal portrait, 1860 | |||||

| Queen of Spain | |||||

| Reign | 29 September 1833 – 30 September 1868 | ||||

| Enthronement | 10 November 1843 | ||||

| Predecessor | Ferdinand VII | ||||

| Successor | Amadeo I (1870) | ||||

| Prime ministers | Full list | ||||

| Regents | Queen María Cristina (1833–1840) Baldomero Espartero (1840–1843) | ||||

| Born | 10 October 1830 Royal Palace of Madrid Madrid, Spain | ||||

| Died | 9 April 1904 (aged 73) Palacio Castilla Paris, France | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue Among others | |||||

| |||||

| House | Bourbon | ||||

| Father | Ferdinand VII | ||||

| Mother | Maria Christina of the Two Sicilies | ||||

| Religion | Catholicism | ||||

| Signature | |||||

Isabella II (Spanish: Isabel II, María Isabel Luisa de Borbón y Borbón-Dos Sicilias; 10 October 1830 – 9 April 1904) was Queen of Spain from 1833 until her deposition in 1868. She is the only queen regnant in the history of unified Spain.[1][n. 1]

Isabella was the elder daughter of King Ferdinand VII and Queen Maria Christina. Shortly before Isabella's birth, her father issued the Pragmatic Sanction to revert the Salic Law and ensure the succession of his firstborn daughter, due to his lack of a son. She came to the throne a month before her third birthday, but her succession was disputed by her uncle Infante Carlos (founder of the Carlist movement), whose refusal to recognize a female sovereign led to the Carlist Wars. Under the regency of her mother, Spain transitioned from an absolute monarchy to a constitutional monarchy, adopting the Royal Statute of 1834 and Constitution of 1837.

Isabella was declared of age and began her personal rule in 1843. Her effective reign was a period marked by palace intrigues, back-stairs and antechamber influences, barracks conspiracies, and military pronunciamientos. Her marriage to Francisco de Asís, Duke of Cádiz was an unhappy one, and her personal conduct as well as rumours of affairs damaged her reputation. In September 1868, a naval mutiny began in Cadiz, marking the beginning of the Glorious Revolution. The defeat of her forces by Marshal Francisco Serrano, 1st Duke of la Torre, brought her reign to an end, and she went into exile in France. In 1870, she formally abdicated the Spanish throne in favour of her son, Alfonso. In 1874, the First Spanish Republic was overthrown in a coup. The Bourbon monarchy was restored, and Alfonso ascended the throne as King Alfonso XII. Isabella returned to Spain two years later but soon again left for France, where she resided until her death in 1904.

Birth and regencies

Isabella was born in the Royal Palace of Madrid in 1830, the eldest daughter of King Ferdinand VII of Spain, and of his fourth wife and niece, Maria Christina of the Two Sicilies. She was entrusted to the royal governess María del Carmen Machín y Ortiz de Zárate. Queen Maria Christina became regent on 29 September 1833, when her three-year-old daughter Isabella was proclaimed sovereign following the death of Ferdinand VII.

Isabella succeeded to the throne because Ferdinand VII had induced the Cortes Generales to help him set aside the Salic law, introduced by the Bourbons in the early 18th century, and to reestablish the older succession law of Spain. The first pretender to the throne, Ferdinand's brother Infante Carlos, Count of Molina, fought for seven years during Isabella's minority to dispute her title (see First Carlist War). The supporters of Carlos and his descendants were known as Carlists, and the fight over the succession was the subject of a number of Carlist Wars in the 19th century.

Isabella's reign was maintained only through the support of the army. The Cortes and the Moderate Liberals and Progressives reestablished constitutional and parliamentary government, dissolved the religious orders and confiscated their property (including that of the Jesuits), and tried to restore order to Spain's finances. After the Carlist war, the regent, Maria Christina, resigned to make way for Baldomero Espartero, Prince of Vergara, the most successful and most popular Isabelline general. Espartero, a Progressive, remained regent for only two years.

Her minority saw tensions with the United States over the Amistad affair.

Baldomero Espartero was deposed in 1843 by a military and political pronunciamiento led by Generals Leopoldo O'Donnell and Ramón María Narváez. They formed a cabinet, presided over by Joaquín María López y López. This government induced the Cortes to declare Isabella of age at 13. Between the beginning of her reign in 1833, and the abdication of Margrethe II of Denmark in 2024, at any given time, there was a queen regnant in Europe.

Reign as an adult

Beginnings

Isabella was declared of age and swore the 1837 Constitution on 10 November 1843,[3] age thirteen. Despite the alleged parliamentary supremacy, in practice, the "double trust" led to Isabella having a role in the making and toppling of governments, undermining the progressives.[4] The uneasy alliance between moderates and progressives that had toppled Espartero in July 1843 was already disintegrating by the time of the coming of age of the queen.[5] Following a brief government led by progressive Salustiano de Olózaga, the moderates elected their candidate, Pedro José Pidal, to the presidency of the Cortes.[5] After the subsequent decision to dissolve the hostile Cortes by Olózaga on 28 November, rumours about an alleged forcing of the queen to sign the royal decree spread. As a result, Olózaga was prosecuted, removed from political office, and forced to exile, with the Progressive Party already being beheaded, in what was the starting point of their growing disaffection from the Isabelline monarchy.[5]

Moderate decade

Dominated by the figure of Marshal Narváez, the Espadón ("Big Sword") of Loja, the so-called "Moderate decade" began in 1844. The constitutional reforms devised by Narváez moved away from the 1837 Constitution by rejecting national sovereignty and reinforcing the power of the monarch, to the point of a "co-sovereignty" between the Cortes and the Queen.[6]

On 10 October 1846, the Moderate Party made their sixteen-year-old queen marry her double-first cousin Francisco de Asís, Duke of Cádiz (1822–1902), the same day that her younger sister, Infanta Luisa Fernanda, married Antoine d'Orléans, Duke of Montpensier.[n. 2] Disgusted by her marriage, Isabella reportedly commented later to one of her intimates: "what shall I tell you about a man whom I saw wearing more lace than I was wearing on our wedding night?"[8]

The marriages suited France and Louis Philippe, King of the French, who as a result bitterly quarrelled with Britain.[9] However, the marriages were not happy; persistent rumour had it that few if any of Isabella's children were fathered by her King Consort, rumoured to be a homosexual. The Carlist party asserted that the heir-apparent to the throne, who later became Alfonso XII, had been fathered by a captain of the guard, Enrique Puigmoltó y Mayans.[10]

In 1847, a major scandal took place when Isabella, age seventeen, publicly showed her love for General Serrano and her willingness to divorce from her husband Francisco de Asís;[11] though Narváez and Isabella's mother Maria Christina solved the problem posed to the monarchical institution—Serrano was shifted away from the capital to the post of Captain General of Granada in 1848—,[12] the deterioration of the public image of the queen increased from then on.[11] Following the near-revolution of 1848, Narváez was authorised to rule as dictator to repress insurrectionary attempts up until 1849.[13]

In late 1851, Isabella II gave birth to her first daughter and heir presumptive, who was baptised on 21 December as María Isabel Francisca de Asís.[14] Historians have attributed the Princess of Asturias' biological parenthood to José Ruiz de Arana,[15] Gentilhombre de cámara.

On 2 February 1852, Isabella and the Royal Guard were caught by surprise while the Queen was leaving the Chapel of the Royal Palace intending to go with her parade to the Basilica of Nuestra Señora de Atocha: Martín Merino y Gómez, an ordained priest and liberal activist approached the queen giving the impression of wanting to deliver her a message,[16] and stabbed her. The impact was reduced by the gold embroidery of her dress and by the baleen stays of her corset, and what was intended to be a stab wound to the chest only resulted in a minor incision at the right side of the belly.[17] Merino, quickly seized by the halberdiers of the Royal Guard (with help from the dukes of Osuna and Tamames, the Marquis of Alcañices and the Count of Pinohermoso),[18] was removed from sacerdocy and executed by garrote.[19]

Under the government of the Count of San Luis (whose ascension to premiership had been solely founded on the support from the networks of the royal court),[20] the system was in a critical state by June 1854.[21] On 28 June 1854 a military pronunciamiento intending to force the queen to oust the government of the Count of San Luis, featuring Leopoldo O'Donnell (a "puritan" moderate), took place in Vicálvaro, the so-called Vicalvarada.[22] The military coup (rather dominated by the moderates themselves) had a mixed result and O'Donnell (advised by Ángel Fernández de los Ríos and Antonio Cánovas del Castillo) proceeded then to seek for civilian support, promising new reforms not in the initial plans in order to appeal to progressives, by bringing a "liberal regeneration", as proclaimed in the Manifesto of Manzanares, drafted by Antonio Cánovas del Castillo and issued on 7 July 1854.[23]

Days later, the situation was followed by a full-scale people's revolution, with revolutionary juntas organised on 17 July in Madrid,[24] and barricades erected in the streets. With the prospect of a civil war on the horizon, Isabella was advised to appoint General Espartero (who enjoyed charisma and popular support) as prime minister.[25][26] This renewed ascension of Espartero marked the beginning of the bienio progresista.

Progressive biennium

Espartero entered the capital of Spain on 28 July,[27] and proceeded to separate again Isabella from the influence of Maria Christina.[28] In any case, though Isabella accepted advice from Maria Christina, she was not characterised for displaying a profound filial love towards her mother.[28]

By virtue of a royal decree, Iloilo in the Philippines was opened to world trade on 29 September 1855, mainly to export sugar and other products to America, Australia and Europe.[29][30]

A Liberal Constitution ("the Unborn One") was drafted in 1856, yet it was never enacted as the counter-revolutionary coup by O'Donnell seized power.

Later reign

On 28 November 1857, Isabella II gave birth to a male heir,[31] who was baptised on 7 December 1857 as Alfonso Francisco de Asís Fernando Pío Juan María Gregorio y Pelagio.[32] Assumed by historians to be the biological son of Enrique Puigmoltó y Mayans,[15] the toddler, who replaced infanta Isabella as Prince of Asturias upon his birth, was known under the moniker el Puigmoltejo, in reference to the rumours about his presumed biological parenthood.[33] Isabella II showed a special affection for the child, greater than that shown to her daughters.[33]

The later part of her reign saw a war against Morocco (1859–1860), which ended in a treaty advantageous for Spain and cession of some Moroccan territory, the Spanish retaking of Santo Domingo (1861–1865), and the fruitless Chincha Islands War (1865–1866) against Bolivia, Chile, Ecuador, and Peru.

Revolution and coup

In August 1866, exiled forces comprising both elements from the Democratic and the Progressive Party met secretly in Belgium and subscribed to the Pact of Ostend under the initiative of Marshal Prim, seeking to topple Isabella.[34] On 7 July 1868, Isabella banished her sister and brother-in-law from Spain, as they were linked to a conspiracy against the Crown in connivance with generals from the Liberal Union.[35]

Since the late summer, Isabella II had been enjoying her traditional holiday on the coast at Lekeitio, Biscay.[36] The royal entourage moved to San Sebastián to hold a meeting with Napoleon III and Eugenia de Montijo, scheduled for 18 September, but it did not take place, as the French royals did not arrive in time and it was subsequently aborted.[37]

On that day, a pronunciamento took place in Cádiz. Led by Marshal Prim and the Admiral Topete (himself an unconditional follower of the Duke of Montpensier),[35] it marked the beginning of the Glorious Revolution.[34] The Democratic Party provided the insurrection with popular support, making it transcend the nature of a simple military statement into an actual revolution.[38]

Factors for the revolution included the weariness of the moderates alienated by the Crown and the progressives barely having even the chance to rule. Both developed a vis-à-vis with the Isabelline monarchy.[39] Other factors were the personal behaviour of the queen, the corruption, the abortion of the possibility of political reform and the economic crisis alienating the bourgeoisie.[39] Historians looking at social roots for the revolution highlight that peasantry, small bourgeoisie, and the proletariat formed an alternative to bourgeoisie proper, articulated through the progressive and federal republican forces.[40]

By September 1868 Isabella was a repudiated monarch, and, during the early stages of the revolution, instances of political iconoclasm carried out by the masses took place, leading to the destruction of many symbols and emblems of the Bourbon dynasty, a Damnatio memoriae.[41]

The defeat of the Isabelline forces commanded by Manuel Pavía y Lacy by the revolutionary forces led by Marshal Serrano at the 28 September 1868 Battle of Alcolea led to the definitive demise of Isabella II's 35-year reign. In the light of the news, Isabella and her entourage left San Sebastián and went to exile taking a train to Biarritz (France) on 30 September.[42] As Isabella entered France after her abdication, her train passed a group of homecoming exiles who taunted her with cries of "Down with the Bourbons!", "Long Live Liberty!" and "Long Live the Republic!".[43]

Prim—leader of the liberal progressives—was received in a festive mood by the Madrilenian people at his arrival in the capital in early October. He pronounced his famous speech of the "three nevers" directed against the Bourbons.[44] At the Puerta del Sol, he gave a highly symbolic hug to Serrano, the leader of the revolutionary forces triumphant in the bridge of Alcolea.[45]

Life after ousting

Following the crossing of the French–Spanish border by train on 30 September, the Queen and King spent 5 weeks in the Château de Pau organising their Parisian future. They went to the French capital and arrived on 8 November, settling in the Rue de Rivoli 172.[46] Isabella was forced to renounce to her dynastic rights in Paris in favour of her son Alfonso on 25 June 1870, officially "freely and spontaneously".[47] Involving an economic settling, the formal separation between Isabella and Francisco had pended on the passing of the former queen's dynastic rights to her son.[48]

Following the election to the Spanish throne of Amadeo of Savoy (second son of Victor Emmanuel II of Italy) in November 1870, Isabella reconciled in 1871 with her brother-in-law, the Duke of Montpensier, who assumed the political management of the family.[49]

The First Spanish Republic that followed Amadeo's short reign was overthrown by a military coup started in Sagunto by General Arsenio Martínez Campos on 29 December 1874 that proclaimed the restoration of the monarchy and the Bourbon dynasty in the person of Isabella's son Alfonso XII,[50] who landed in Barcelona on 9 January 1875.[51]

After 1875 she lived in a relationship with Ramiro de la Puente y González Nandín, her secretary and chief of staff.[52]

Cánovas del Castillo, the dominant figure of the new regime, became convinced that the figure of Isabella had become an issue for the Crown and wrote her a letter bluntly stating "Your Majesty is not a person, it is a reign, it is a historical time, and what the country needs is another reign, a different time", hellbent on avoiding the former queen stepping onto the Spanish capital before the proclamation of the new constitution in June 1876.[53]

She returned to Spain in July 1876, stayed in Santander and El Escorial and was only allowed to visit Madrid for barely hours on 13 October.[53] She moved to Seville, where she remained for a longer time and left for France in 1877.[53] Isabella's son would marry Mercedes of Orléans (first cousin of Alfonso and daughter of the Dukes of Montpensier) in 1878, only for the latter to die five months after the wedding.[49]

Isabella mostly lived in Paris for the rest of her life, based at the Palacio Castilla. She paid some visits to Seville.[53]

She wrote her testament in Paris in June 1901, making her will to be entombed in El Escorial.[54] Less than a month after passing through a cold categorised as "flu" by the physicians, she died on 9 April 1904, at 8:45 AM.[55] Her corpse was moved from the Palacio Castilla to the Gare d'Orsay,[56] and arrived to El Escorial on 15 April.[57] The funeral took place on the next day at San Francisco el Grande.[58]

Issue

Isabella had twelve pregnancies, but only five children reached adulthood:[59][60]

- Infante Luis Fernando (20 May 1849), stillbirth.

- Infante Fernando Francisco (12 July 1850), dead five minute after his birth.

- Infanta María Isabel (1851–1931): married her mother's and father's first cousin Prince Gaetan, Count of Girgenti.

- Infanta Maria Cristina (5 January 1854 - 7 January).

- Infanta Margarita (23 September 1855 - 24 September 1855), she was born prematurely.

- Infante Francisco de Asis Fernando (21 December 1856), stillbirth.

- Alfonso XII of Spain (1857–1885) Future King of Spain.

- Infanta Maria de la Conception (1859 - 21 October 1861).

- Infanta María del Pilar (1861–1879).

- Infanta María de la Paz (1862–1946); married her paternal first cousin Prince Louis Ferdinand of Bavaria.

- Infanta María Eulalia (1864–1958); married her maternal first cousin Infante Antonio d'Orléans, Duke of Galliera.

- Infante Francisco de Asis Leopoldo Maria Enrique (24 January 1866 - 14 February 1866).

There has been considerable speculation that some or all of Isabella's children were not fathered by Francisco de Asís; this has been bolstered by rumours that Francisco de Asís was either homosexual or impotent. Francisco de Asís recognised all of them: he played the offended, proceeding to blackmail the queen to receive money in exchange for keeping his mouth shut.[59] The extortion by her husband would continue and intensify during Isabella's exile.[61]

Sobriquets

She came to be known by the sobriquets of the Traditional Queen (Spanish: la Reina Castiza),[n. 3] and the Queen of Sad Mischance (Spanish: la de los Tristes Destinos).[n. 4]

Honours

Spain: Dame of the Order of Queen Maria Luisa, 10 October 1830[65]

Spain: Dame of the Order of Queen Maria Luisa, 10 October 1830[65] Austria: Knight Grand Cordon with Collar of the Royal Hungarian Order of Saint Stephen[66]

Austria: Knight Grand Cordon with Collar of the Royal Hungarian Order of Saint Stephen[66] Austria: Dame of the Order of the Starry Cross, 1st Class[66]

Austria: Dame of the Order of the Starry Cross, 1st Class[66] Brazil: Knight Grand Cordon of the Imperial and Royal Order of Christ[66]

Brazil: Knight Grand Cordon of the Imperial and Royal Order of Christ[66] Brazil:: Knight Grand Cordon with Collar of the Imperial and Royal Order of the Southern Cross, 1848[66]

Brazil:: Knight Grand Cordon with Collar of the Imperial and Royal Order of the Southern Cross, 1848[66]- France

Bourbon-French Royal Family: Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Order of the Holy Spirit

Bourbon-French Royal Family: Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Order of the Holy Spirit Bourbon-French Royal Family: Knight Grand Cross with Collar of the Royal Order of Saint Michael

Bourbon-French Royal Family: Knight Grand Cross with Collar of the Royal Order of Saint Michael French Imperial Family: Knight Grand Cordon with Collar of the Imperial Order of the Legion of Honour[66]

French Imperial Family: Knight Grand Cordon with Collar of the Imperial Order of the Legion of Honour[66]

Bavaria: Knight Grand Cross with Chain of the Order of Saint Hubert[66]

Bavaria: Knight Grand Cross with Chain of the Order of Saint Hubert[66] Bavaria: Dame Grand Cross of the Order of Theresa[66]

Bavaria: Dame Grand Cross of the Order of Theresa[66] Bavaria: Dame Grand Cross of the Order of Saint Elizabeth[66]

Bavaria: Dame Grand Cross of the Order of Saint Elizabeth[66] Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the White Falcon, 1 November 1861[67]

Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the White Falcon, 1 November 1861[67] Saxony: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Rue Crown[66]

Saxony: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Rue Crown[66] Saxony: Dame Grand Cross of the Order of Sidonia[66]

Saxony: Dame Grand Cross of the Order of Sidonia[66] Saxony: Dame of the Order of Maria-Anna, Special Class[66]

Saxony: Dame of the Order of Maria-Anna, Special Class[66] Greece: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Redeemer[66]

Greece: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Redeemer[66]- Italy

Italian Royal Family: Knight Grand Collar of the Supreme Order of the Most Holy Annunciation

Italian Royal Family: Knight Grand Collar of the Supreme Order of the Most Holy Annunciation Italian Royal Family: Knight Grand Cordon of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus

Italian Royal Family: Knight Grand Cordon of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus Italian Royal Family: Knight Grand Cordon of the Order of the Crown of Italy

Italian Royal Family: Knight Grand Cordon of the Order of the Crown of Italy Holy See: Knight Grand Cross with Collar of the Supreme Order of Christ[66]

Holy See: Knight Grand Cross with Collar of the Supreme Order of Christ[66] Two Sicilian Royal Family: Knight Grand Cross with Collar of the Order of Saint Januarius[68]

Two Sicilian Royal Family: Knight Grand Cross with Collar of the Order of Saint Januarius[68] Two Sicilian Royal Family: Bailiff Knight Grand Cross with Collar of the Two Sicilian Sacred Military Constantinian Order of Saint George

Two Sicilian Royal Family: Bailiff Knight Grand Cross with Collar of the Two Sicilian Sacred Military Constantinian Order of Saint George

- Mexico

Mexican Republic: Knight Grand Cross with Collar of the National Order of Guadalupe, 1854[69]

Mexican Republic: Knight Grand Cross with Collar of the National Order of Guadalupe, 1854[69] Mexican Imperial Family: Dame Grand Cross of the Imperial Order of Saint Charles, 10 April 1865[70]

Mexican Imperial Family: Dame Grand Cross of the Imperial Order of Saint Charles, 10 April 1865[70]

Monaco: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Saint-Charles, 17 September 1865[66][71]

Monaco: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Saint-Charles, 17 September 1865[66][71] Portugal: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Immaculate Conception of Vila Viçosa, 23 June 1834[66]

Portugal: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Immaculate Conception of Vila Viçosa, 23 June 1834[66] Portugal: Knight Grand Cross with Collar of the Order of the Tower and Sword[66]

Portugal: Knight Grand Cross with Collar of the Order of the Tower and Sword[66] Portugal: Dame Grand Cross of the Order of Saint Isabel[66]

Portugal: Dame Grand Cross of the Order of Saint Isabel[66]

Honorific eponyms

Philippines:

Philippines:

- Cavite: Bridge of Isabel II

- Isabela (province)

- Isabela, Basilan

- Manila: El Banco Español Filipino de Isabel II former name of the current Bank of the Philippine Islands.

Puerto Rico:

Puerto Rico:

- Isabel II: barrio-pueblo (referred to as Isabel Segunda in Spanish) is a barrio and the administrative center (seat) in the downtown area in the island-municipality of Vieques, Puerto Rico.

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Isabella II | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Film portrayal

In the 1997 film Amistad, she was played by Anna Paquin, and is depicted as a spoiled 11-year-old girl.

See also

- Philip V of Spain – monarch who implemented a Salic Law in the country

- Carl Schurz, who was U.S. ambassador to Spain for a brief time at the beginning of Lincoln's presidency, in his Reminiscences (New York, McClure's Publ. Co., 1907, Volume II, Chapter VI) describes Isabel II and her court.

- Isabela province in the Philippines.

- Mid-19th-century Spain

- Spain under the Restoration

- Plaza de Isabel II (Santa Cruz de Tenerife)

References

- Informational notes

- ^ She was formally Queen of Spain, unlike Isabella I, who was proclaimed Queen of Castile, although the latter is nevertheless sometimes considered to have also been Queen of Spain.[2]

- ^ Isabella and Francisco de Asís were rather caustically described by 1866 by an English contemporary thus:

- … The Queen is large in stature, but rather what might be called bulky than stately. There is no dignity either in her face or figure, and the graces of majesty are altogether wanting. The countenance is cold and expressionless, with traces of an unchastened, unrefined, and impulsive character, and the indifference it betrays is not redeemed by any regularity or beauty of feature.

- The King Consort is much smaller in figure than his royal two-thirds, and certainly is not a type that could be admired for its manly qualifications; but we have to remember that in Spain aristocratic birth is designated rather by a diminutive stature and sickly complexion than by those attributes of height, muscular power, open expression, and florid hue, which in England constitute the ideal of ‘race.’[7]

- ^ Due to her fondness for traditional Spanish cultural expressions in connection with Casticismo and Casticismo madrileño.[62]

- ^ After the 1907 work by Benito Pérez Galdós, La de los tristes destinos, part of the Episodios Nacionales. The use of the name in reference to Isabella II, however, dates back to 4 July 1865, when Antonio Aparisi Guijarro[63] took the nickname from a verse in Shakespeare's Richard III. Thus, in Act IV-Scene IV, Queen Margaret tells Queen Elizabeth:

- Farewell, York’s wife, and queen of sad mischance: These English woes shall make me smile in France.

- Citations

- ^ Monarchy and Liberalism in Spain: The Building of the Nation-State, 1780–1931. United Kingdom, Taylor & Francis, 2020.

- ^ "Kings and Queens Regnant of Spain". Britannica. 31 October 2023.

- ^ Cobo del Rosal Pérez, Gabriela (2011). "Los mecanismos de creación normativa en la España del siglo XIX a través de la codificación penal". Anuario de Historia del Derecho Español (81): 935. ISSN 0304-4319.

- ^ Moliner Prada, Antonio (2019). "Liberalismo y cultura política liberal en la España del siglo XIX" (PDF). Revista de História das Ideias. 37. Coimbra: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra: 228. doi:10.14195/2183-8925_37_9. ISSN 0870-0958. S2CID 244017803.

- ^ a b c Pérez Alonso, Jorge (2013). "Ramón María Narváez: biografía de un hombre de estado. El desmontaje de la falsa leyenda del "Espadón de Loja"" (PDF). Historia Constitucional: Revista Electrónica de Historia Constitucional (14): 539–540. ISSN 1576-4729.

- ^ Beltrán Villalva, Miguel (2005). "Clases sociales y partidos políticos en la década moderada (1844–1854)". Historia y política: Ideas, Procesos y Movimientos Sociales (13). UCM; UNED; CEPC: 49–78. ISSN 1575-0361.

- ^ Mrs. Wm. Pitt Byrne, Cosas De España, Illustrative of Spain and the Spaniards as they are, Volume II, Page 7, Alexander Strahan, Publisher, London and New York, 1866.

- ^ Sánchez Núñez, Pedro (2014). "El Duque de Montpensier, entre la historia y la leyenda" (PDF). Temas de Estética y Arte (28). Seville: Real Academia de Bellas Artes de Santa Isabel de Hungría: 219. ISSN 0214-6258.

- ^ Jasper Ridley, Lord Palmerston (1970) pp. 308–315.

- ^ Juan Sisinio Pérez Garzón, Isabel II: Los Espejos de la Reina (2004)

- ^ a b Burdiel 2012, p. 33.

- ^ Domingo, M.R. (13 February 2015). "Serrano, el amante de Isabel II que dio nombre a la calle más comercial de Madrid". ABC.

- ^ Beltrán Villalva 2005, p. 50.

- ^ Cambronero 1908, p. 168.

- ^ a b Esteban Monasterio, Agustín (2009). "Sexenio Revolucionario y Restauración" (PDF). Aportes. XXIV (69): 119.

- ^ Cambronero 1908, pp. 170–171.

- ^ Paniagua, Antonio (14 October 2016). "El corsé de la reina". Diario Sur.

- ^ Cambronero 1908, p. 172.

- ^ Sanz, Víctor (2 February 2018). "Puñalada en el costado en nombre de Martín Merino". Madridiario.

- ^ Núñez García, Víctor Manuel; Calero Delgado, María Luisa (2018). "Corrupción y redes de poder en la Corte Isabelina" (PDF). La corrupción política en la España contemporánea: un enfoque interdisciplinar. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-02-23. Retrieved 2020-08-22.

- ^ Fernández Trillo, Manuel (1982). "La Vicalvarada y la Revolución Española de 1854" (PDF). Tiempo de Historia. VIII (87): 17.

- ^ Fernández Trillo 1982, p. 18–19.

- ^ Fernández Trillo 1982, pp. 18–20.

- ^ Fernández Trillo 1982, p. 25.

- ^ Cambronero 1908, p. 188.

- ^ Fernández Trillo 1982, p. 27.

- ^ Cambronero 1908, p. 192.

- ^ a b Cambronero 1908, p. 194.

- ^ Demy Sonza. "The Port of Iloilo: 1855–2005". Graciano Lopez-Jaena Life and Works and Iloilo History Online Resource. Dr. Graciano Lopez-Jaena (DGLJ) Foundation, Inc. Archived from the original on 2016-01-19.

- ^ Henry Funtecha. "Iloilo's position under colonial rule". thenewstoday.info.

- ^ Cambronero 1908, p. 210.

- ^ Fernández Sirvent, Rafael. "Biografía de Alfonso XII de Borbón (1875–1885)". Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes.

- ^ a b Vilches, Jorge (30 June 2017). "El puñal del godo en la familia Borbón". El Español.

- ^ a b "¿Por qué España echó a la reina Isabel II?". XLSemanal. 17 October 2018.

- ^ a b Sánchez Núñez 2014, p. 219.

- ^ Vilar García 2012, pp. 246–247.

- ^ Vilar García 2012, pp. 248–249.

- ^ Vilar García 2012, p. 249.

- ^ a b Quintero Niño, Emna Mylena (2018). "Evolución histórica del estado y la consolidación del constitucionalismo liberal español" (PDF). Auctoritas: Revista On-Line de Historiografía en Historia, Derecho e Interculturalidad (3): 49. ISSN 2530-4127.

- ^ Serrano García, Rafael (2001). "La historiografía en torno al Sexenio 1868-1874: entre el fulgor del centenario y el despliegue sobre lo local" (PDF). Ayer. 44: 15.

- ^ Sánchez Collantes, Sergio (2019). "Iconoclasia antiborbónica en España el repudio simbólico de Isabel II durante la Revolución de 1868" (PDF). Historia Constitucional: Revista Electrónica de Historia Constitucional (20): 25; 29. doi:10.17811/hc.v0i20.593. ISSN 1576-4729. S2CID 204383086.

- ^ Vilar García 2012, p. 251.

- ^ Carmen, Ennesch (1946). Emigrations politiques, d'hier et d'aujourd'hui (in French). Paris: Editions I.P.C. p. 161.

- ^ Cañas de Pablos 2018, p. 212.

- ^ Cañas de Pablos 2018, pp. 212–213.

- ^ Reyero 2020, pp. 209–210.

- ^ Congostrina, Nieves (25 June 2018). "a crucial decisión de Isabel II".

- ^ Reyero 2020, p. 220.

- ^ a b Sánchez Núñez 2014, p. 220.

- ^ Layana, César. "El sistema político de la Restauración". Clío.

- ^ Sust, Toni (25 February 2018). "Otras visitas de los Borbones a Barcelona". El Periódico.

- ^ Fernández Albéndiz, María del Carmen (2007). Sevilla y la monarquía: las visitas reales en el siglo XIX. Seville: Universidad de Sevilla. p. 275. ISBN 978-84-472-0911-8.

- ^ a b c d Álvarez, Eduardo (20 June 2020). "Isabel II de España: cuando abdicar supuso tener prohibido pisar el país". El Mundo.

- ^ Cambronero 1908, pp. 332–333.

- ^ Cambronero 1908, pp. 328–329.

- ^ Cambronero 1908, pp. 329.

- ^ Cambronero 1908, p. 330.

- ^ Cambronero 1908, p. 334.

- ^ a b Domínguez, Mari Pau (25 August 2018). "Isabel II: la supremacía de los instintos". ABC.

- ^ Campos, Carlos Robles do. ""Los Infantes de España tras la derogación de la Ley Sálica (1830)"" (PDF). Real Academia Matritense de Heráldica y Genealogía. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-08-19. Retrieved 2024-08-16.

- ^ Reyero 2020, p. 217.

- ^ Vanity Fair (10 October 2020): «Isabel II de España: la reina que tuvo 12 hijos sin consumar su matrimonio»

- ^ El Diario Montañés (22 July 2008): «Isabel II: 'la de los tristes destinos'»

- ^ Vilches 2006, p. 776.

- ^ "Real orden de damas nobles de la Reina Maria Luisa", Calendario Manual y Guía de Forasteros en Madrid (in Spanish): 57, 1832, retrieved 14 November 2020

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q , VV. AA., Boletín de la Real Academia de la Historia, Tomo CLXXVI, Cuaderno I, 1979, Real Academia de la Historia, Madrid, España, páginas = 211 & 220, español, 6 de junio de 2010 Information Containing the Orders and Decorations received by Isabella II of her European tour after her coming of age to reign as Queen

- ^ Staatshandbuch für das Großherzogtum Sachsen / Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach (1864), "Großherzogliche Hausorden" p. 13 Archived 2019-08-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "GENEALOGY OF THE ROYAL HOUSE OF SPAIN". Chivalricorders.org. Retrieved 2017-05-23.

- ^ "Seccion IV: Ordenes del Imperio", Almanaque imperial para el año 1866 (in Spanish), 1866, p. 244, retrieved 14 November 2020

- ^ "Soberanas y princesas condecoradas con la Gran Cruz de San Carlos el 10 de Abril de 1865" (PDF), Diario del Imperio (in Spanish), National Digital Newspaper Library of Mexico: 347, retrieved 14 November 2020

- ^ Sovereign Ordonnance of 17 September 1865

- ^ a b Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b Ortúzar Castañer, Trinidad. "María Cristina de Borbón dos Sicilias". Diccionario biográfico España (in Spanish). Real Academia de la Historia.

- ^ a b Genealogie ascendante jusqu'au quatrieme degre inclusivement de tous les Rois et Princes de maisons souveraines de l'Europe actuellement vivans [Genealogy up to the fourth degree inclusive of all the Kings and Princes of sovereign houses of Europe currently living] (in French). Bourdeaux: Frederic Guillaume Birnstiel. 1768. p. 9.

- ^ a b Genealogie ascendante jusqu'au quatrieme degre inclusivement de tous les Rois et Princes de maisons souveraines de l'Europe actuellement vivans [Genealogy up to the fourth degree inclusive of all the Kings and Princes of sovereign houses of Europe currently living] (in French). Bourdeaux: Frederic Guillaume Birnstiel. 1768. p. 96.

- ^ a b Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b Navarrete Martínez, Esperanza. "María de la O Isabel de Borbón". Diccionario biográfico España (in Spanish). Real Academia de la Historia. Archived from the original on 2020-08-02. Retrieved 2019-03-29.

- Bibliography

- Burdiel, Isabel (2012). "El descenso de los reyes y la nación moral. A propósito de Los Borbones en pelota". Los borbones en pelota (PDF). Zaragoza: Institución Fernando el Católico. pp. 7–74. ISBN 978-84-9911-196-4.

- Cambronero, Carlos (1908). Isabel II, íntima; apuntes histórico-anecdóticos de su vida y de su época. Barcelona: Montaner y Simón, Editores.

- Cañas de Pablos, Alberto (2018). "La revolución de puerto en puerto hacia la capital: la vertiente marítima de la "Gloriosa" y la llegada de Prim a Madrid". Cuadernos de Historia Contemporánea. 40. Madrid: Ediciones Complutense: 199–218. doi:10.5209/CHCO.60329. ISSN 0214-400X.

- Reyero, Carlos (2020). "Cuando el rey Francisco de Asís perdió el aura regia. Caricatura y vida cotidiana en el París del Segundo Imperio (1868-1870)". Libros de la Corte (20). Madrid: Universidad Autónoma de Madrid: 207–234. doi:10.15366/ldc2020.12.20.007. hdl:10486/694703. ISSN 1989-6425.

- Vilar García, María José (2012). "El primer exilio de Isabel II visto desde la prensa vasco-francesa (Pau, septiembre-noviembre 1868)". Historia Contemporánea. 44. Bilbao: Universidad del País Vasco/Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea: 241–270. ISSN 1130-2402.

- Vilches, Jorge (2006). "La política en la literatura. La creación de la imagen pública de Isabel II en Galdós y Valle-Inclán". Historia Contemporánea. 33. Bilbao: Universidad del País Vasco/Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea: 769–788. ISSN 1130-2402.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Isabella II". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 859–860.

Further reading

- Barton, Simon. A History of Spain (2009) excerpt and text search

- Carr, Raymond, ed. Spain: A History (2001) excerpt and text search

- Esdaile, Charles J. Spain in the Liberal Age: From Constitution to Civil War, 1808–1939 (2000) excerpt and text search

- Gribble, Francis Henry. The tragedy of Isabella, II (1913) online.

- de Polnay, Peter. A Queen of Spain: Isabel II (1962)