International use of the U.S. dollar

The United States dollar was established as the world's foremost reserve currency by the Bretton Woods Agreement of 1944. It claimed this status from sterling after the devastation of two world wars and the massive spending of the United Kingdom's gold reserves. Despite all links to gold being severed in 1971, the dollar continues to be the world's foremost reserve currency. Furthermore, the Bretton Woods Agreement also set up the global post-war monetary system by setting up rules, institutions and procedures for conducting international trade and accessing the global capital markets using the U.S. dollar.

The U.S. dollar is widely held by central banks, foreign companies and private individuals worldwide, in the form of eurodollar foreign deposit accounts (not to be confused with the euro), as well as in the form of US$100 notes, an estimated 75% of which are held overseas.[1] The U.S. dollar is predominantly the standard currency unit in which goods are quoted and traded, and with which payments are settled in, in the global commodity markets.[2]

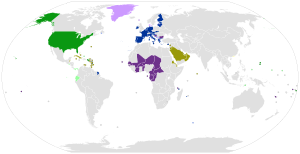

The U.S. dollar is also the official currency in several countries and the de facto currency in many others, with Federal Reserve Notes (and, in a few cases, U.S. coins) used in circulation.

The monetary policy of the United States is conducted by the Federal Reserve System, which acts as the nation's central bank.

Ascendancy

The primary currency used for trade around the world, between Europe, Asia and the Americas had historically been the Spanish-American silver dollar, which created a global silver standard system from the 16th to 19th centuries, due to abundant silver supplies in Spanish America.[3] The U.S. dollar itself was derived from this coin. The Spanish dollar was later displaced by sterling in the advent of the international gold standard in the last quarter of the 19th century.

The U.S. dollar began to displace sterling as international reserve currency from the 1920s since it emerged from the First World War relatively unscathed and since the United States was a significant recipient of wartime gold inflows. [4] After the US emerged as an even stronger global superpower during the Second World War, the Bretton Woods Agreement of 1944 established the post-war international monetary system, with the U.S. dollar ascending to become the world's primary reserve currency for international trade, and the only post-war currency linked to gold at $35 per troy ounce.[5] Despite all links to gold being severed in 1971, the dollar continues to play this role to this day.

International reserve currency

The U.S. dollar is joined by the world's other major currencies – the euro, sterling, Japanese yen and Chinese renminbi – in the currency basket of the Special drawing rights of the International Monetary Fund. Central banks worldwide have huge reserves of U.S. dollars in their holdings, and are significant buyers of US treasury bills and notes.[6]

Foreign companies, entities and private individuals hold U.S. dollars in foreign deposit accounts called eurodollars (not to be confused with the euro), which are outside the jurisdiction of the Federal Reserve System. Private individuals also hold dollars outside the banking system mostly in the form of US$100 notes, of which 75% of its supply are held overseas.

The United States Department of the Treasury exercises considerable oversight over the SWIFT financial transfers network,[7] and consequently has a huge sway on the global financial transactions systems, with the ability to impose sanctions on foreign entities and individuals.[8] Some countries have considered dollar alternatives to avoid sanctions.[9]

Economist Paul Samuelson and others (including, at his death, Milton Friedman) have maintained that the overseas demand for dollars allows the United States to maintain persistent trade deficits without causing the value of the currency to depreciate or the flow of trade to readjust. But Samuelson stated in 2005 that at some uncertain future period these pressures would precipitate a run against the U.S. dollar with serious global financial consequences.[10]

In August 2007, two scholars affiliated with the government of the People's Republic of China threatened to sell its substantial reserves in American dollars in response to American legislative discussion of trade sanctions designed to revalue the Chinese yuan.[11] The Chinese government denied that selling dollar-denominated assets would be an official policy in the foreseeable future. India and Russia have also announced moves to diversify reserves away from the U.S. dollar.[12]

After the euro's share of global official foreign exchange reserves approached 25% as of year-end 2006 (vs 65% for the U.S. dollar; see table in Reserve currency#Global currency reserves), former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan said in September 2007 that it is "absolutely conceivable that the euro will replace the dollar as reserve currency, or will be traded as an equally important reserve currency".[13] As of 2021, however, none of this has come to fruition due to the European debt crisis which engulfed the PIIGS countries from 2009-2014. Instead the euro's stability and future existence was put into doubt, which reduced its share of global reserves to 19% as of year-end 2015 (vs 66% for USD). As of year-end 2020 these figures stand at 21% for EUR and 59% for USD.

The percental composition of currencies of official foreign exchange reserves from 1995 to 2022.[14][15][16]

In the global markets

The U.S. dollar is predominantly the standard currency unit in which goods are quoted and traded, and with which payments are settled in, in the global commodity markets.[2] See petrocurrency, petrodollar.

The United States Government is capable of borrowing trillions of dollars from the global capital markets in U.S. dollars issued by the Federal Reserve, which is itself under US government purview, at minimal interest rates and with virtually zero default risk. In contrast, foreign governments and corporations incapable of raising money in their own local currencies are forced to issue debt denominated in U.S. dollars, along with its consequent higher interest rates and risks of default.[17] The United States's ability to borrow in its own currency without facing significant balance of payments crisis has been frequently described as its exorbitant privilege.[18]

U.S. dollar Index

The U.S. dollar Index (ticker: USDX) is the creation of the New York Board of Trade (NYBOT), renamed in September 2007 to ICE Futures US. It was established in 1973 for tracking the value of the USD against a basket of currencies, which, at that time, represented the largest trading partners of the United States. It began with 17 currencies from 17 nations, but the launch of the euro subsumed 12 of these into one, so the USDX tracks only six currencies today.

| Currency | Relative value of other currency |

|---|---|

| Euro | 57.6% |

| Japanese yen | 13.6% |

| Sterling | 11.9% |

| Canadian dollar | 9.1% |

| Swedish krona | 4.2% |

| Swiss franc | 3.6% |

The Index is described by the ICE as "a geometrically-averaged calculation of six currencies weighted against the U.S. dollar."[19] The baseline of 100.00 on the USDX was set at its launch in March 1973. This event marks the watershed between the wider margins arrangement of the Smithsonian regime and the period of generalized floating that led up to the Second Amendment of the Articles of Agreement of the International Monetary Fund. Since 1973, the USDX has climbed as high as the 160s and drifted as low as the 70s.

The USDX has not been updated to reflect new trading realities in the global economy, where the bulk of trade has shifted strongly towards new partners like China and Mexico and oil-exporting countries while the United States has de-industrialized.

Dollarization and fixed exchange rates

Other nations besides the United States use the U.S. dollar as their official currency, a process known as official dollarization. For instance, Panama has been using the dollar alongside the Panamanian balboa as the legal tender since 1904 at a conversion rate of 1:1. Ecuador (2000), El Salvador (2001), and East Timor (2000) all adopted the currency independently. The former members of the U.S.-administered Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, which included Palau, the Federated States of Micronesia, and the Marshall Islands, chose not to issue their own currency after becoming independent, having all used the U.S. dollar since 1944. Two British dependencies also use the U.S. dollar: the British Virgin Islands (1959) and Turks and Caicos Islands (1973). The islands Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba, now collectively known as the Caribbean Netherlands, adopted the dollar on January 1, 2011, as a result of the dissolution of the Netherlands Antilles.[20][21]

The U.S. dollar is an official currency in Zimbabwe, along with the euro, sterling, the pula, the rand, and several other currencies. A series of Zimbabwean Bond Coins was put into circulation on 18 December 2014 in 1, 5, 10, and 25 cent denominations, and afterwards 50 cent and 1 dollar bonds coins, which are pegged at the same rate as American coins.

Some countries that have adopted the U.S. dollar issue their own coins: See Ecuadorian centavo coins, Panamanian Balboa and East Timorese centavo coins.

Some other countries link their currency to U.S. dollar at a fixed exchange rate. The local currencies of Bermuda and the Bahamas can be freely exchanged at a 1:1 ratio for USD. Argentina used a fixed 1:1 exchange rate between the Argentine peso and the U.S. dollar from 1991 until 2002. The currencies of Barbados and Belize are similarly convertible at an approximate 2:1 ratio. The Netherlands Antillean guilder (and its successor the Caribbean guilder) and the Aruban florin are pegged to the dollar at a fixed rate of 1:1.79. The East Caribbean dollar is pegged to the dollar at a fixed rate of 2.7:1, and is used by all of the countries and territories of the OECS other than the British Virgin Islands. In Lebanon, one dollar is equal to 15000 Lebanese pounds, and is used interchangeably with local currency as de facto legal tender.[22] The exchange rate between the Hong Kong dollar and the United States dollar has also been linked since 1983 at HK$7.8/USD, and pataca of Macau, pegged to Hong Kong dollar at MOP1.03/HKD, indirectly linked to the U.S. dollar at roughly MOP 8/USD. Several oil-producing Arab countries on the Persian Gulf, including Saudi Arabia, peg their currencies to the dollar, since the dollar is the currency used in the international oil trade.

The People's Republic of China's renminbi was informally and controversially pegged to the dollar in the mid-1990s at ¥ 8.28/USD. Likewise, Malaysia pegged its ringgit at RM3.8/USD in September 1998, after the financial crisis. On July 21, 2005, both countries removed their pegs and adopted managed floats against a basket of currencies. Kuwait did likewise on May 20, 2007.[23] However, after three years of slow appreciation, the Chinese yuan has been de facto re-pegged to the dollar since July 2008 at a value of ¥6.83/USD; although no official announcement had been made, the yuan has remained around that value within a narrow band since then, similar to the Hong Kong dollar.

Several countries use a crawling peg model, wherein currency is devalued at a fixed rate relative to the dollar. For example, the Nicaraguan córdoba is devalued by 5% per annum.[24]

Belarus, on the other hand, pegged its currency, the Belarusian rubel, to a basket of foreign currencies (U.S. dollar, euro and Russian rouble) in 2009.[25] In 2011 this led to a currency crisis when the government became unable to honor its promise to convert Belarusian rubels to foreign currencies at a fixed exchange rate. BYR exchange rates dropped by two thirds, all import prices rose and living standards fell.[26]

In some countries, such as Costa Rica and Honduras, the U.S. dollar is commonly accepted, although not officially regarded as legal tender. In Mexico's northern border area and major tourist zones, it is accepted as if it were a second legal currency. Many Canadian merchants close to the border, as well as large stores in big cities and major tourist hotspots in Peru also accept U.S. dollars, though usually at a value that favours the merchant. In Cambodia, US notes circulate freely and are preferred over the Cambodian riel for large purchases,[27][28] with the riel used for change to break 1 USD. After the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan, U.S. dollars were accepted as if legal tender, but in 2021 the Taliban government banned the use of foreign currencies.[29]

Dollar versus euro

| Year | Highest ↑ | Lowest ↓ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Rate | Date | Rate | |||

| 1999 | 03 Dec | €0.9985 | 05 Jan | €0.8482 | ||

| 2000 | 26 Oct | €1.2118 | 06 Jan | €0.9626 | ||

| 2001 | 06 Jul | €1.1927 | 05 Jan | €1.0477 | ||

| 2002 | 28 Jan | €1.1658 | 31 Dec | €0.9536 | ||

| 2003 | 08 Jan | €0.9637 | 31 Dec | €0.7918 | ||

| 2004 | 14 May | €0.8473 | 28 Dec | €0.7335 | ||

| 2005 | 15 Nov | €0.8571 | 03 Jan | €0.7404 | ||

| 2006 | 02 Jan | €0.8456 | 05 Dec | €0.7501 | ||

| 2007 | 12 Jan | €0.7756 | 27 Nov | €0.6723 | ||

| 2008 | 27 Oct | €0.8026 | 15 Jul | €0.6254 | ||

| 2009 | 04 Mar | €0.7965 | 03 Dec | €0.6614 | ||

| 2010 | 08 Jun | €0.8374 | 13 Jan | €0.6867 | ||

| 2011 | 10 Jan | €0.7750 | 29 Apr | €0.6737 | ||

| 2012 | 24 Jul | €0.8272 | 28 Feb | €0.7433 | ||

| 2013 | 27 Mar | €0.7832 | 27 Dec | €0.7239 | ||

| 2014 | 31 Dec | €0.8237 | 8 May | €0.7167 | ||

| 2015 | 13 Apr | €0.9477 | 2 Jan | €0.8304 | ||

| Source: Euro exchange rates in USD, ECB | ||||||

Not long after the introduction of the euro (€; ISO 4217 code EUR) as a cash currency in 2002, the dollar began to depreciate steadily in value, as it did against other major currencies. From 2003 to 2005, this depreciation continued, reflecting a widening current account deficit. Although the current account deficit began to stabilize in 2006 and 2007, depreciation persisted. The fallout from the subprime mortgage crisis in 2008 prompted the Federal Reserve to lower interest rates in September 2007,[30] and again in March 2008,[31] sending the euro to a record high of $1.6038, reached in July 2008. [32] In addition to the trade deficit, the U.S. dollar's decline was linked to a variety of other factors, including a major spike in oil prices.[33]

However, a sharp turnaround began in late 2008 with the onset of the global financial crisis. As investors sought out safe-haven investments in U.S. treasuries and Japanese government bonds from the financial turmoil, the Japanese yen and United States dollar sharply rose against other currencies, including the euro.[34] The European sovereign debt crisis that unfolded in 2010 sent the euro falling to a four-year low of $1.1877 on June 7, as investors considered the risk that certain Eurozone members may default on their government debt.[35] The euro's decline in 2008-2010 had erased half of its 2000-2008 rally.[32]

Chinese-issued U.S. dollar bonds

The issuance of U.S dollar-denominated bond issued by Chinese institutions doubled to $214 billion in 2017 as tighter domestic regulations and market conditions saw Chinese companies look offshore to conduct their fund-raising initiatives. This has far outpaced many of the other major foreign currency bonds issued in Asia in the last few years.

The anticipated continuation of a prudent monetary policy in China to curb financial risks and asset bubbles, along with the expectation of a stronger yuan will likely see Chinese companies to continue to issue U.S. dollar bonds.[36]

Major issuers of U.S. dollar denominated bonds have included Tencent Holdings Limited, Industrial and Commercial Bank of China Limited and Sinopec Group. In 2017, China's Ministry of Finance revealed plans to sell US$2 billion worth of U.S. dollar sovereign bonds in Hong Kong, its first dollar bond offering since October 2004.[37] The technology and communications sector in China is a taking significant share of the offshore U.S. dollar bond market. Tencent priced $5 billion of notes in January 2018 as a string of Asian technology firms continued to issue debt as market values swelled.[38]

U.S dollar-denominated bond issued by Chinese institutions has also been referred to as "Kungfu bonds",[39] a name born out of a consultation with more than 400 market participants across Asia by Bloomberg L.P.[40][41]

See also

- Reserve currency

- Dollarization and Dedollarisation

- Internationalization of the renminbi

- International status and usage of the euro

- List of the largest trading partners of the United States

References

- ^ "The Death of Cash? Not So Fast: Demand for U.S. Currency at Home and Abroad, 1990-2016" (PDF). www.econstor.eu/. 2017-05-25. p. 8. Retrieved 2017-05-25.

- ^ a b Kowalski, Chuck (February 11, 2020). "Impact of the Dollar on Commodities Prices". The Balance.

- ^ Babones, Salvatore (April 30, 2017). "'The Silver Way' Explains How the Old Mexican Dollar Changed the World". The National Interest.

- ^ Eichengreen, Barry; Flandreau, Marc (2009). "The rise and fall of the dollar (or when did the dollar replace sterling as the leading reserve currency?)". European Review of Economic History. 13 (3): 377–411. doi:10.1017/S1361491609990153. ISSN 1474-0044. S2CID 154773110.

- ^ Amadeo, Kimberly (September 3, 2020). "How a 1944 Agreement Created a New World Order". The Balance.

- ^ "Major foreign holders of U.S. treasury securities 2021". Statista.

- ^ "SWIFT oversight". SWIFT - The global provider of secure financial messaging services.

- ^ "Sanctions Programs and Country Information". U.S. Department of the Treasury.

- ^ Abdelhady, Hdeel (11 June 2015). "A Great BRIC Wall? Emerging Trade and Finance Channels Could Curtail the Reach of U.S. Law". masspointpllc.com. Retrieved 29 September 2024.

- ^ "China, U.S. should adjust approach to economic growth". English.people.com.cn. 2005-12-26. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- ^ Evans-Pritchard, Ambrose (2007-08-08). "China threatens 'nuclear option' of dollar sales". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 2007-08-09. Retrieved September 26, 2007.

- ^ Chris Buckley (2008-09-17). "China paper urges new currency order after "financial tsunami"". Reuters. Retrieved 2009-09-18.

- ^ "Reuters". Euro could replace dollar as top currency - Greenspan. 2007-09-17. Retrieved September 17, 2007.

- ^ For 1995–99, 2006–22: "Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER)". Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. April 3, 2023.

- ^ For 1999–2005: International Relations Committee Task Force on Accumulation of Foreign Reserves (February 2006), The Accumulation of Foreign Reserves (PDF), Occasional Paper Series, Nr. 43, Frankfurt am Main: European Central Bank, ISSN 1607-1484ISSN 1725-6534 (online).

- ^ Review of the International Role of the Euro (PDF), Frankfurt am Main: European Central Bank, December 2005, ISSN 1725-2210ISSN 1725-6593 (online).

- ^ Chen, James (May 17, 2021). "Dollar Bond". Investopedia.

- ^ "The dollar's international role: An "exorbitant privilege"?". 30 November 2001.

- ^ a b "The ICE U.S. Dollar Index and US Dollar Index Futures Contracts US Dollar Index" (PDF). June 2012. p. 2. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- ^ "Introduction of the US dollar on Bonaire, St Eustatius and Saba". sxmislandtime.com. 26 May 2010. Retrieved 2010-10-22.

- ^ "US dollar introduced in Dutch Caribbean islands". Radio Netherlands Worldwide. 1 Jan 2011. Archived from the original on 2016-02-02. Retrieved 2011-01-02.

- ^ "Lebanon devalues official exchange rate by 90%". Reuters. February 1, 2023. Retrieved February 3, 2023.

- ^ "Kuwait pegs dinar to basket of currencies". Forbes. 2007-05-20. Archived from the original on November 10, 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-06.

- ^ Rogers, Tim (May 13, 2014). "Nicaragua seeks to de-dollarize economy". The Nicaragua Dispatch.

- ^ "New exchange rate will make Belarusian exports competitive, NBRB vows". State Customs Committee of the Republic of Belarus. 2009-01-06. Archived from the original on 2012-03-23. Retrieved 2009-01-24.

- ^ "Belarusian rouble falls sharply in value". BBC News. 2011-09-14.

- ^ Chinese University of Hong Kong. "Historical Exchange Rate Regime of Asian Countries: Cambodia". Archived from the original on 2006-12-08. Retrieved 2007-02-21.

- ^ Kurt Schuler. "Tables of Modern Monetary History: Asia". Archived from the original on 2007-02-19. Retrieved 2007-02-21.

The U.S. dollar also circulates freely

- ^ "Taliban bans foreign currencies in Afghanistan". BBC News. 3 November 2021.

- ^ "ECB: euro exchange rates USD". Ecb.int. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- ^ "Dollar Falls to Record Low Versus Euro as Fed Signals Rate Cuts". Bloomberg. 2008-03-01.

- ^ a b Worrachate, Anchalee; Seki, Yasuhiko (2008-06-01). "Euro Weakens on Concerns Over Europe Spending Cuts". Bloomberg.

- ^ "Oil Rises to Record on Weakening Dollar, Morgan Stanley Outlook". Bloomberg. 2008-06-06.

- ^ David Gaffen (2008-10-22). "Somehow, the Dollar Regains Safe-Haven Status". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved October 22, 2008.

- ^ Levisohn, Ben; Worrachate, Anchalee (2008-06-10). "Euro Climbs Most Versus Dollar in Two Weeks on Outlook for Global Growth". Bloomberg.

- ^ Li Xiang (2018-01-03). "Sales of bonds look set to rise this year". China Daily. Retrieved 2018-11-27.

- ^ Karen Yeung (2017-10-11). "China to sell first dollar bond in 13 years in Hong Kong to set benchmark for Chinese issuers". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 2018-11-27.

- ^ Manju Dalal (2018-01-12). "Tencent Joins Asia-Tech Debt Rush With Its Biggest Bond Sale". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2018-11-27.

- ^ Ishika Mookerjee (2018-04-04). "'Kung Fu' bonds grab investor attention". Citywire Asia. Retrieved 2018-11-27.

- ^ Ee Chuan Ng (2018-04-13). "'Gongfu bonds become bright spot with Asian investors as Chinese US$ bonds take off". The Business Times. Retrieved 2018-11-27.

- ^ Vicky Wei, Andrew Cheung, Wenwen Zhang (2018-04-19). "'Baidu, Tencent sales give Kungfu bonds a hi-tech kick in 2018". Bloomberg Professional Services. Retrieved 2018-11-27.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)