Howden Minster

| Howden Minster | |

|---|---|

| Minster Church of St Peter and St Paul | |

Howden Minster, East Riding of Yorkshire | |

| |

| 53°44′43″N 0°52′02″W / 53.745300°N 0.867200°W | |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Churchmanship | Anglo-Catholic |

| Website | Official website |

| History | |

| Dedication | St Peter and St Paul |

| Administration | |

| Province | York |

| Diocese | York |

| Archdeaconry | East Riding |

| Deanery | Howden |

| Parish | Howden Minster |

| Clergy | |

| Rector | The Rev James Little |

| Vicar(s) | The Rev Lyn Kenny |

| Laity | |

| Organist/Director of music | Matthew Collins |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Designated | 16 December 1966 |

| Reference no. | 1160491 |

Howden Minster (also known as the Minster Church of St Peter and St Paul, Howden) is a large Grade I listed Church of England church in the Diocese of York.[1] It is located in Howden, East Riding of Yorkshire, England and is one of the largest churches in the East Riding. It is dedicated to St Peter and St Paul and it is therefore properly known as 'the Minster Church of St Peter and St Paul'. Its Grade I listed status also includes the Chapter House.

History

There has been a church at Howden since Anglo-Saxon times, and it has always been on the same site. Before the Conquest, it was owned by monks from Peterborough Abbey. But the only remnants from those earlier churches is a Norman corbel table on the east wall of the north transept.

The bishops of Durham came into possession of the manor of Howden in 1086–7, during the tenure of William de St-Calais (1081–96). The town and surrounding area benefited from this connection: the bishops secured a weekly market and four annual fairs for Howden before the 13th century. The great income of the parish church meant that it became prebendal in the 1220s, then achieved collegiate status in 1265 or 1267, its income being divided between a college of five, and later six, canons who carried out the daily offices of worship. This was the status quo until the English Reformation, when England's chantries and collegiate foundations were abolished and Howden lost its canons and their patronage. The see of Durham retained the manor until the 17th century.

Rebuilding of the church began almost immediately after collegiate status was achieved, and not under a bishop's patronage but that of one of the original canons, John of Howden, chaplain to Eleanor of Provence. An aisleless choir was built first, then the crossing and aisled transepts which still stand, along with the first bay of the nave aisle walls. John's death in 1272 brought construction to a halt, and the priest was buried in the choir he had funded. Probably after a break of several years, the nave was continued westward, the south porch built, and the structure completed with the construction of the west front from c. 1308. During this second phase, the decision was made to introduce a clerestory over the nave arcades; that it was an afterthought is revealed by the former lower roofline above the west crossing arch, and by the squat proportions of the clerestory itself. All this was finished by about 1311, judging from both heraldic and stylistic evidence.[2][3]

It must have been shortly thereafter that Canon John's choir was deemed inadequate and rebuilt on a much grander scale. The new choir was designed with aisles and a clerestory from the start, vaulted in stone and brick (unlike the earlier parts of the church), and given a bold and magnificent east front. This campaign was probably underway by 1320, and surely finished, like nearby contemporary work at Selby, by c. 1335. A chapter house was then begun off the south choir aisle, but only recommenced in 1380 after £10 was endowed by Henry de Snaith, canon of Howden, Lincoln, and Beverley. This is the last of the octagonal English chapter houses to be built. But the "climax of the exterior" (Pevsner) is the 135-foot (41-metre) crossing tower, funded by Walter Skirlaw, bishop of Durham (1388–1405). At Skirlaw's death it was unfinished, and the bishop bequeathed £40 for its completion. The late 15th century saw the tower's upper stage added, and a grammar school was built off the south nave aisle c. 1500.[1][3]

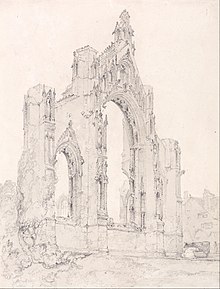

At the Reformation, the college was dissolved and Howden Minster became a parish church. After years of neglect and controversy over who was responsible for the upkeep of the fabric, the choir vaults fell in 1696. The choir was walled off, the altar moved to the crossing, and the eastern portion of the church descended into ruin. The chapter house vault collapsed in 1750. Nave and tower underwent restoration by Weightman & Hadfield in 1852–5, and the grammar school in 1863 by Jonathan Parsons. A fire damaged the tower and crossing in 1929, requiring restoration that was completed in 1932. Recent restoration has also stayed the rate of decay in the ruined east end.[2][3][4]

The ruins are now in the guardianship of English Heritage, preserved by the Department of the Environment, and are in the condition of a 'safe ruin'. The chapter house received a new roof in 1984.[5] The portions of the Minster still used as Howden's parish church are freely open to the public on most days between 9:30 am and 3:30 pm.[6] However, the choir ruins must be viewed from the exterior as there is generally no public access to them.[7]

Architecture and furnishings

First construction campaign (1265–1311)

Surviving from John's church then are the transepts, the crossing, and the first bay of the nave aisle walls. The transept elevation is simple, with one storey (i.e., an arcade with no clerestory), and the roofs are of wood. The piers are quatrefoil in section, with four shafts separated by concave hollow mouldings and a fillet on each shaft. This pier form would be used in all subsequent construction campaigns at Howden Minster, with the only changes being in the form of the capitals. Large traceried windows occur throughout, including the easternmost window of each nave aisle. The tracery is pure geometrical, exactly what one would expect of the 1260s. The transept end windows have four cusped lights divided into pairs with a quatrefoiled oculus above each pair and a sexfoiled oculus over the two pairs; the side windows have three cusped lights with three quatrefoiled oculi stacked over them. Both these patterns are taken directly from the recently built Angel Choir at Lincoln Cathedral; Nicola Coldstream writes that ‘the mason of Howden may well have introduced them to Yorkshire’. The geometrical designs would go on to be used in a group of high status Yorkshire buildings: Selby Abbey, St Mary's Abbey in York, and York Minster chapter house among them, and Southwell Minster in Nottinghamshire.[3]

The break between Canon John's work and the next phase is easily discerned, as the tracery patterns change completely and the elements are no longer encircled. The aisle windows are all of three lights, and alternate on both sides between pointed trefoils (some of them inverted) stacked over the lights, and intersecting Y-tracery with pointed trefoils and turned quatrefoils in the interstices. These motifs support John Bilson’s claim that the nave was built from 1280 onward.[3] The nave is six bays long and the nave arcades are higher than those of the transept, the capitals changing from round with octagonal abaci to octagonal throughout. It is obvious from the lower roofline above the western crossing arch that a clerestory was not originally employed. But a clerestory was introduced in the second campaign, though it is rather low in comparison with the arcades. There are two clerestory windows to each bay, with a rounded quatrefoil over two pointed-trefoil lights in each window. These open into the church through two corresponding arches with continuous mouldings, and there is a passage in the thickness of the wall.

The arms of Antony Bek, Bishop of Durham from 1308 to 1311, which appeared in stained glass of the northwest window suggest that the west front was constructed during those years under his patronage. This is not disputed by the overall form of the west front, with four emphatic turrets and the tops of the aisle walls finished horizontally, a common northern type based on the east facades of Ely and Lincoln. And the dates of Bek's episcopate are supported by the architectural details, mainly adapted from the work at York Minster around 1300. The gable over the central window, panels of blind tracery, decorative motifs including impaled trefoils and pointed quatrefoils, and a specific tracery pattern of alternating round and pointed trefoils within a circle: all are motifs taken from York Minster, and all point to a completion date no later than about 1310, before the appearance of the fully curvilinear forms of the upper west front of York Minster. At the same time, the ogee curves that do occur in the west aisle windows push the construction date right up to that time.

The central window has four lights with pointed-trefoil heads grouped in pairs: over each pair are impaled pointed trefoils and a larger pointed quatrefoil, and over the two pairs at the apex of the window is a large pointed and subcusped quatrefoil in a lozenge. The verticality of this window has been somewhat negated by the insertion of a Perpendicular transom. The aisle windows have three lights and an oculus above, which is entirely filled with alternating rounded and pointed trefoils. The mullions bend in slight ogees as they meet the oculus, and ogees occur again as the heads of the external lights merge with the lower parts of pointed trefoils either side of the oculus. Blind tracery flanks the west door and the great west window, and occurs on the nave buttresses along with canopied statues. The tracery motifs used in the main façade are employed again on the octagonal openwork turrets, surmounted by crocketed spirelets, that crown the buttresses. Blind arcades on the interior of the west front feature foliage carving similar to contemporary work at York Minster and Selby Abbey.[2][3]

Rebuilding of choir (early 14th century)

In about 1311, then, when the west front was completed, the church had been rebuilt in its entirety over the preceding 45 years. But very soon thereafter, the choir was deemed inadequate and stonemasons once more returned to Howden to build a new eastern arm, on a much grander scale than the former one. Their work is now in ruins, and very weathered, but its original quality and aesthetic appeal cannot be questioned. The new choir was planned from the outset with a two-storey elevation of arcade and high clerestory, with aisles and quadripartite vaulting, and with a square east end as was usual in England. At six bays, it was to be as long as the nave, bringing the total length of the minster to 78 metres (255 feet) and making it one of the Riding's largest churches. In 1848, Edmund Sharpe brought together the remaining architectural evidence in two reconstruction drawings for his Architectural Parallels, one of an interior elevation, one of the east front.

Of the 13th-century choir only a roofline against the tower and the double capitals on the responds below give evidence. Of the new choir, the aisle walls remain mostly intact with some tracery, the east front stands to its full height, and the east and west responds survive with some remnants of the arcade and clerestory walls still attached to them. That the master mason used a number of the same elements employed in the earlier work suggests that the choir was begun was only a short time after the work on the nave was completed. The east front again follows the Lincoln form; decorative details again draw on the ideas expressed in the York nave. Gables occur over the windows of the south aisle (facing the bishop's manor house) and the east front, but not on the north elevation (facing the town). Stacked foils occur in the three-light aisle windows, this time using rounded quatrefoils as in the York Minster aisles, but with continuous mouldings and, interestingly, ogee forms as the head of the central light merges with the intersection of the two lower quatrefoils; this ogee is repeated in the top and bottom lobes of the upper quatrefoil. The buttresses throughout are closely related to the York Minster nave buttresses, with traceried decoration, and their elaborate pinnacles suggest to Nicola Coldstream that the design included flying buttresses.

Though externally the north and south choir walls had much in common with the work of the nave, the similarities stopped there. From the interior, the only commonality with the nave was the pattern for the piers, four filleted shafts separated by four concave hollows, though the capitals here were foliate. The clerestory consisted of a single wide arch on the inner plane of each bay and a large corresponding three-light window on the exterior plane of the wall, with a wall passage between the two planes. The inner arch filled the whole bay, and was fenced along its bottom edge by a parapet of turned pointed quatrefoils. The clerestory windows were reconstructed by Sharpe with reticulated tracery; according to Nicola Coldstream an 1813 drawing by Buckler shows that this is almost certainly correct. The quadripartite vaults were of stone, or rather stone ribs with brick infilling, and were almost certainly carried on shafts corbelled in above the arcades.[2][3]

This elevation has a very close parallel in the choir of Selby Abbey, under construction at roughly the same time only eleven miles away. The east fronts of the two churches are also similar, again following Lincoln's example, with built-up aisle walls and massive buttresses ending in emphatic turrets, as well as a large traceried window filling the gable to light the roof space. But whereas Selby's east front is plain, with almost no surface decoration, Howden's is a spectacularly ornamented composition and powerfully effective even in a weathered state with the tracery, turrets, and gable cross destroyed and much detail missing. The outer buttresses have panels of blind tracery, a grotesque above, and above that a gabled and pinnacled statue niche. The aisle windows have crocketed gables in thin relief, and their tracery is ‘convincingly reconstructed’ (Coldstream) by Sharpe as partially reticulated. Below all three windows ran a small openwork parapet. The inner buttresses each have four gabled and pinnacled niches stacked one above the other, and rosette diaper at windowsill level. The entire façade is dominated by the great east window of seven lights, flanked by statue niches at its base on the exterior jambs and the interior embrasures. In the spandrels above, six more overlapping niches rise toward the gable window. These niches were aligned with the (now non-existent) mullions of the central window, resulting in a series of vertical lines that punctuated the façade. The upper window had reticulated tracery, and the gable over the great east window intersected its lower corners, continuing as tracery within it (an idea taken from the west front of York Minster, which was even then still under construction). The upper window was in turn gabled as well, with pinnacles that intersected the coping stones above.[3]

As for the tracery in the east window, Sharpe's reconstruction shows it with seven lights rising toward a wheel in the tracery above, surrounded by fantastical converging mouchettes. This pattern is very closely related to the east window at Selby Abbey, and shows that Sharpe thought of Howden's east window as a link between geometrical forms and the spectacular fully curvilinear window at Selby. This is certainly possible chronologically if construction began at Howden (as it did at Selby) with the east front. Stylistically the Howden east front could comfortably be dated to c. 1320, and work at Selby was begun in the 1320s. And Sharpe could show that the upper tracery of the two great windows was the same; but his reconstruction of the lower tracery, while entirely possible, cannot be proven. These fantastical tracery patterns would go on to be employed and developed in a group of well-known Decorated churches in Lincolnshire: Heckington, Sleaford, and Algarkirk, as well as Hawton just over the border into Nottinghamshire. Heckington can indeed be linked to Howden through the use of the Howden pier form at the entrance to the chancel.[3]

The use of brick (as described earlier) for the vault infilling was a rare thing for that time in England. It is surely no coincidence that the first use of brick for a major building project was in the transepts of Hull Minster, built from 1300 to 1320 only twenty-six miles east of Howden. The same method of vaulting would also be used a few decades later in the nave of Beverley Minster, also in the East Riding, built from 1308–c. 1350.[8]

Chapter house and later additions

With the vaults completed, the masons at Howden turned to the building of a chapter house off the south choir aisle. Only the substructure, however, was built during the Decorated period: there can be no doubt that the parts below window level, including the entry passage, the portal itself, and the interior seats predate 1350. Everything above that level is Perpendicular, however, the work being recommenced in 1380 after a long intermission: in that year Henry de Snaith, canon of Howden, Lincoln, and Beverley, bequeathed £10 for the completion of the chapter house. Bishop Skirlaw (1388–1405) also contributed to the chapter house project, and founded a chantry c. 1404. As the chapel between the chapter house and the choir is of the early 15th century, it was probably connected with Skirlaw's chantry. A chamber was built at the same time over the chapter house passage, likely as a room for the chantry priest. Nor did Skirlaw's patronage stop there; for it was he who funded the construction of the first stage of the present crossing tower. It was unfinished at the bishop's death in 1405, and he left £40 to finish it. It is a ‘veritable stone cage’ (Pevsner), with immensely tall three-light double-transomed windows and the wall space reduced to the width of the buttresses. A shorter second stage was added later in the century and the tower reached a height of 41 metres (135 feet). The windows this time featured basket arches and single transoms, and the tower was topped off with an embattled parapet: a common motif in late medieval ecclesiastical architecture symbolising the secular authority of the church as well as its strength as a bastion against evil. Other than the crossing tower, Howden Minster underwent few structural additions from the 15th century on. The south transept chapel, first the Metham chantry then the Saltmarshe chantry, was renovated during the Perpendicular period. It contains a number of medieval monuments to members of both families. A grammar school was added on to the south nave aisle c. 1500. The windows are under basket arches, but with two-centred arches struck through the Perpendicular tracery. Pevsner mentions the staircase to the upper school room with its tiny fan vault, and the excellent view of the Decorated nave elevation from the upper room itself.[1][2]

Furnishings

A magnificent stone pulpitum with four statues was installed in the 15th century (it is now of course the reredos, due to the loss of the choir). Along with this two stone screens were installed across the entrances to the chancel aisles. These have niches which now contain sculpture from the east front. Another furnishing worth mentioning is the earlier octagonal Decorated font, of 1320–50. The only surviving medieval stained glass, fragmentary and mainly of the 14th century, is in the south porch.[2]

St John of Howden

John was one of the earliest canons of Howden, who was treated as a saint by the local community after his death, although he has not been officially canonised. Pilgrims, including Kings Edward I, Edward II and Henry V visited the Minster to see his tomb. He had a reputation as a poet in Norman French and Latin, writing on religious and lyrical subjects, and had been clerk or confessor to Queen Eleanor of Provence, the wife of King Henry III.[9] He was responsible for the rebuilding of the choir of the minster. He died in 1275 and was buried in a shrine in the choir. The tomb survived until the 16th century. His feast day is 2 May.[10]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Historic England. "Minster Church Of St Peter And St Paul And Chapter House, Howden (1160491)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Pevsner, Nikolaus; Neave, David; Hutchinson, John; Neave, Susan (2002). Yorkshire: York and the East Riding. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 485–90. ISBN 0300095937.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Coldstream, Nicola (1989). Wilson, Christopher (ed.). St Peter's Church, Howden. Leeds: W. S. Maney and Son Limited. pp. 109–118. ISBN 0901286222.

- ^ "History of Howden Minster". English Heritage. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

- ^ Burn, Chris (21 May 2018). "Church ruins offer elaborate window to the past". The Yorkshire Post. p. 20. ISSN 0963-1496.

- ^ "Find Us – Howden Minster (St Peter and St Paul)". A Church Near You. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ "History of Howden Minster". English Heritage. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ Pevsner, Nikolaus; Neave, David; Hutchinson, John; Neave, Susan (2002). Yorkshire: York and the East Riding. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 289, 485, 505. ISBN 0300095937.

- ^ Peach, Howard (2001). Curious Tales of Old East Yorkshire. Sigma Leisure. p. 182. ISBN 1850587493.

- ^ Little, James. "A Brief history of the Minster An Introduction to Howden Minster:". The Church of England. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- Keeton, Revd. Canon Barry (2000) Howden Minster, A Guide Book.

External links

- History of Howden Minster: English Heritage

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1160491)". National Heritage List for England.

- Howden Minster exterior on YouTube (a good video overview of the exterior focusing mainly on the ruined eastern portion of the building)