LGBTQ bullying

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| LGBTQ topics |

|---|

|

|

Bullying of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer (LGBTQ) people, particularly LGBTQ youth, involves intentional actions toward the victim, repeated negative actions by one or more people against another person, and an imbalance of physical or psychological power.[1]

LGBTQ youth are more likely to report bullying than non-LGBTQ youth.[2] In one study, boys who were bullied with taunts of being gay suffered more bullying and more negative effects compared with boys who were bullied with other categories of taunting.[3] Some researchers suggest including youth questioning their sexuality in any research on LGBTQ bullying because they may be as susceptible to its effects as LGBTQ students.[4][5][6]

Victims of LGBTQ bullying may feel unsafe, resulting in depression and anxiety, including increased rates of suicide and attempted suicide. LGBTQ students may try to pass as heterosexual and/or cisgender to escape the bullying, leading to further stress and isolation from available supports. Support organizations exist in many countries to prevent LGBTQ bullying and support victims. Some jurisdictions have passed legislation against LGBTQ bullying and harassment.

Schools

Homophobic and transphobic violence in schools can be categorized as explicit and implicit. Explicit homophobic and transphobic violence consists of overt acts that make subjects feel uncomfortable, hurt, humiliated or intimidated. Peers and educational staff are unlikely to intervene when witnessing these incidents. [citation needed] This contributes to normalizing such acts that become accepted as either a routine disciplinary measure or a means to resolve conflicts among students. Homophobic and transphobic violence – as with all school-related gender-based violence – is acutely underreported due to subjects' fear of retribution, combined with inadequate or non-existent reporting, support and redress systems.[7][8][9][10] The absence of effective policies, protection or remedies contributes to a vicious cycle where incidents become increasingly normal.[11]

Implicit homophobic and transphobic violence, sometimes called 'symbolic violence' or 'institutional' violence, is subtler than explicit violence. It consists of pervasive representations or attitudes that sometimes feel harmless or natural to the school community, but that allow or encourage homophobia and transphobia, including perpetuating harmful stereotypes. Policies and guidelines can reinforce or embed these representations or attitudes, whether in an individual institution or across an entire education sector. This way, they can become part of everyday practices and rules guiding school behaviour.[12][13][11] Examples of implicit homophobic and transphobic violence include:

- Asserting that some subjects are better suited to students based on their sexual orientation or gender identity/expression (for example, science for heterosexual male students and drama for gay male students).

- Suggesting that it is normal for heterosexual students to have greater agency or influence (for example, with the opinions of LGBTI students treated as marginal and unimportant).

- Reinforcing stereotypes related to sexual orientation or gender identity/expression in curriculum materials or teacher training, such as through images and discourse (for example, that refer to heterosexuality as 'normal').

- Reinforcing stereotypes related to sexual orientation or gender identity/expression in educational policies, rules and regulations (for example, by not even acknowledging that LGBTI students are part of the school community and by not specifying them in relevant policies).[11]

Egale Canada, along with previous research, has found teachers and school administration may be complicit in LGBT bullying through their silence and/or inaction.[14][15][16][4]

Graffiti found on school grounds and property, and its "relative permanence",[16] is another form of LGBT bullying.

American sociologist Michael Kimmel and American psychologist Gregory Herek write that masculinity is a renunciation of the feminine and that males shore up their sense of their masculinity by denigrating the feminine and ultimately the homosexual.[17][18] Building on the notion of masculinity defining itself by what it is not, some researchers suggest that in fact the renunciation of the feminine may be misogyny.[15][16] These intertwining issues were examined in 2007, when American sociologist CJ Pascoe described what she calls the "fag discourse" at an American high school in her book, Dude, You're a Fag.

Effects

Victims of LGBT bullying may feel chronically depressed, anxious, and unsafe in the world.[19][20] Bullying will affect a student's experience of school. Some victims might feel paralyzed and withdraw socially as a coping mechanism.[14] Others may begin to live the effects of learned helplessness.[20]

LGBT and questioning youth who experience bullying have a higher incidence of substance abuse and sexually transmitted infections.[5][21][22] LGBT bullying may also be seen as a manifestation of what American academic Ilan Meyer calls minority stress, which may affect sexual and ethno-racial minorities attempting to exist within a challenging broader society.[23]

Gay and lesbian youth can develop severe forms of depression and anxiety as they grow up. Around 70% of LGBT people experience major depressive disorder (MDD) sometime in their lives.[24] For LGBT individuals, MDD can be caused by any of the following: self-esteem, pressure to conform, minority stress, coming out, family rejection, parenting, relationship formation, and violence.[25] A person can be harassed to the point where their depression becomes too much and they no longer experience any happiness. These factors all work together and make it extremely hard to avoid MDD.[25]

The rate of suicide is higher among LGBT people:

- In a study conducted by the Schools Education Unit for UK charity Stonewall, an online survey reported that 71 percent of the girl participants who identified as LGBTQ, and 57 percent of the boy participants who identified as LGBTQ had seriously considered suicide.[26]

- According to a 1979 Jay and Young study, 40 percent of gay men and 39 percent of gay women in the US had attempted or seriously thought about suicide.[27]

- The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention has found that gay, lesbian and bisexual youth attempt suicide at a rate three to six times that of similar-age heterosexual youth.[28]

- In 1985, F. Paris estimated that suicides by gay youth may comprise up to 30 percent of all youth suicides in the US. This contributes to suicide being the third leading cause for death among youth aged 10–24, reported by the CDC.[29]

LGBT or questioning students may try to pass as heterosexual in order to avoid LGBT bullying. Passing isolates the student from other LGBT or questioning students, potential allies, and support.[16] Adults who try to pass also may feel the effects emotionally and psychologically, of this effort to conceal their true identities.[18]

Statistics

Canada

Egale Canada conducted a survey of more than 3,700 high school students in Canada between December 2007 and June 2009. The final report of the survey, "Every Class in Every School",[30] published in 2011, found that 70% of all students participating heard "that's so gay" daily at school, and 48% of respondents heard "faggot", "lezbo" and "dyke" daily. 58% or about 1,400 of the 2,400 heterosexual students participating in EGALE's survey found homophobic comments upsetting. Further, EGALE found that students not directly affected by homophobia, biphobia or transphobia were less aware of it. This finding relates to research done in the area of empathy gaps for social pain which suggests that those not directly experiencing social pain (in this case, bullying) consistently underestimate its effects and thus may not adequately respond to the needs of one experiencing social pain.[31]

United Kingdom

About two-thirds of gay and lesbian students in British schools have suffered from gay bullying in 2007, according to a study done by the Schools Education Unit for LGBT activist group Stonewall. Almost all that had been bullied had experienced verbal attacks, 41 percent had been physically attacked, and 17 percent had received death threats. It also showed that over 50% of teachers did not respond to homophobic language which they had explicitly heard in the classroom, and only 25% of schools had told their students that homophobic bullying was wrong, showing "a shocking picture of the extent of homophobic bullying undertaken by fellow pupils and, alarmingly, school staff",[32] with further studies conducted by the same charity in 2012 stated that 90% of teachers had had no training on the prevention of homophobic bullying. However, Ofsted's new 2012 framework did ask schools what they would be doing in order to combat the issue.[33]

A research study of 78 eleven to fourteen-year-old boys conducted in twelve schools in London, England between 1998 and 1999[15] revealed that respondents who used the word "gay" to label another boy in a derogatory manner intended the word as "just a joke", "just a cuss" and not as a statement of one's perceived sexual orientation.[16][34]

United States

A 1998 study in the US by Mental Health America found that students heard anti-gay slurs such as "homo", "faggot" and "sissy" about 26 times a day on average, or once every 14 minutes.[35] In a study conducted by the Association of Teachers and Lecturers, a union for UK professionals, the word "gay" was reported to be the most popular term of abuse heard by teachers on a regular basis.[36]

Cases

United Kingdom

- Damilola Taylor was attacked by a local gang of youths on November 27, 2000, in Peckham, South London; he bled to death after being stabbed with a broken bottle in the thigh, which severed the femoral artery. The BBC, Telegraph, Guardian and Independent newspapers reported at the time that during the weeks between arriving in the UK from Nigeria and the attack he had been subjected to bullying and beating, which included homophobic remarks by a group of boys at his school.[37][38][39][40] In the New Statesman two years later, when there had still been no convictions for the crime, Peter Tatchell, gay human rights campaigner, said, "In the days leading up to his murder in south London in November 2000, he was subjected to vicious homophobic abuse and assaults,"[41] and asked why the authorities had ignored this before and after his death.

United States

- In 1996, Jamie Nabozny won a landmark lawsuit (Nabozny v. Podlesny) against officials at his former public high school in Ashland, Wisconsin over their refusal to intervene in the "relentless antigay verbal and physical abuse by fellow students" to which he had been subjected and which had resulted in his hospitalization.[42]

- High school student Derek Henkle faced inaction from school officials when repeatedly harassed by his peers in Reno, Nevada. His lawsuit against the school district and several administrators ended in a 2002 settlement in which the district agreed to create a series of policies to protect gay and lesbian students and to pay Henkle $451,000.[43]

- Tyler Clementi committed suicide on September 22, 2010, after his roommate at Rutgers University secretly recorded his sexual encounter with another man.[44]

- Kenneth Weishuhn, a 14-year-old freshman from South O'Brien High School in Iowa, hanged himself in his family's garage after intense anti-gay bullying, cyberbullying and death threats in 2012. His suicide was covered nationally and raised questions about what culpability bullies have in suicides.[45][46]

- Jadin Bell, a 15-year-old youth in La Grande, Oregon, tried to commit suicide by hanging after intense anti-gay bullying at his high school in 2013. After life support was removed, Bell died at the OHSU hospital. His father Joe Bell started a walk across America to raise awareness about gay bullying, but was hit and killed by a truck halfway through his journey.[47][48]

Support organizations

- Safe schools coalitions in various countries provide anti-bullying resources for teachers and students.[citation needed]

- The US It Gets Better Project involves celebrities and ordinary LGBT people making YouTube videos and sharing messages of hope for gay teens.[49][50][51] The organization works with USA, The Trevor Project[50] and the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network.[51]

- Egale Canada is a rights organization with a mandate that includes promoting safer schools.

- In Brazil, the Gay Group of Bahia provides support.[52][53][54]

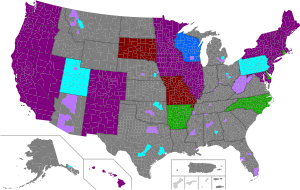

Anti-LGBT bullying legislation

In 2000, the state of California enacted the California Student Safety and Violence Prevention Act (AB 537), a bill that prohibits harassment and discrimination on the basis of perceived or actual gender identity or sexual orientation.[55]

The state of Illinois passed a law (SB3266) in June 2010 that prohibits gay bullying and other forms of bullying in schools.[56]

In the Philippines, legislators implemented Republic Act No. 10627, otherwise known as the Anti-Bullying Act of 2013, in schools. According to the said law, gender-based bullying is defined as ˮany act that humiliates or excludes a person on the basis of perceived or actual sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI)ˮ.[57]

Sources

![]() This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC-BY-SA IGO 3.0 (license statement/permission). Text taken from Out in the Open: Education sector responses to violence based on sexual orientation and gender identity/expression, 26, UNESCO, UNESCO. UNESCO.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC-BY-SA IGO 3.0 (license statement/permission). Text taken from Out in the Open: Education sector responses to violence based on sexual orientation and gender identity/expression, 26, UNESCO, UNESCO. UNESCO.

References

- ^ "Bullying Myths and Facts". US Dept of Education. Archived from the original on March 25, 2010. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- ^ Berlan, ED; Corliss, HL; Field, AE; et al. (April 2010). "Sexual Orientation and Bullying Among Adolescents in the Growing Up Today Study". Journal of Adolescent Health. 46 (4): 366–71. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.10.015. PMC 2844864. PMID 20307826.

- ^ Swearer, SM; Turner, RT; Givens, JE (2008). ""You're so gay!": Do different forms of bullying matter for adolescent males?". School Psychology Review. 37 (2): 160–173. doi:10.1080/02796015.2008.12087891. S2CID 6456413.

- ^ a b Swearer, S. M.; Turner, R. K.; Givens, J. E.; Pollack, W. S. (2008). "You're So Gay!": Do Different Forms of Bullying Matter for Adolescent Males?". School Psychology Review. 37 (2): 160–173. doi:10.1080/02796015.2008.12087891. S2CID 6456413.

- ^ a b Russell, S. T.; Joyner, K. (2001). "Adolescent Sexual Orientation and Suicide Risk: Evidence From a National Study". American Journal of Public Health. 91 (8): 1276–1281. doi:10.2105/ajph.91.8.1276. PMC 1446760. PMID 11499118.

- ^ Williams, T.; Connolly, J.; Pepler, D.; Craig, W. (2005). "Peer Victimization, Social Support, and Psychosocial Adjustment of Sexual Minority Adolescents" (PDF). Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 34 (5): 471–482. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.459.218. doi:10.1007/s10964-005-7264-x. S2CID 56253666. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 8, 2017. Retrieved November 1, 2017.

- ^ GMR, UNESCO, and UNGEI, 'School-related gender-based violence is preventing the achievement of quality education for all: Policy Paper 17 at 59th session of the Commission on the Status of Women in New York City', 59th session of the Commission on the Status of Women in New York City. UNESCO, p. 16, 2015.

- ^ Plan International, 'A Girl's Right to Learn Without Fear: Working to end gender-based violence at school', Plan Limited, Surrey, 2013.

- ^ S. Bloom, J. Levy, N. Karim, L. Stefanik, M. Kincaid, D. Bartel, and K. Grimes, 'Guidance for Gender Based Violence (GBV) Monitoring and Mitigation within Non-GBV Focused Sectoral Programming', CARE USA, 2014.

- ^ Plan UK, 'Ending school-related gender-based violence: Brie ng paper', London, 2013.

- ^ a b c UNESCO (2016). Out in the Open: Education sector responses to violence based on sexual orientation and gender identity/expression (PDF). Paris, UNESCO. p. 26. ISBN 978-92-3-100150-5.

- ^ ICGBV, 'Addressing School Related Gender Based Violence: Learning from Practice: Learning Brief No. 10', Irish Consortium on Gender Based Violence, Dublin, 2013.

- ^ F. Leach, M. Dunne, and F. Salvi, 'School-Related Gender based Violence: A global review of current issues and approaches in policy, programming and implementation responses to School-Related Gender-Based Violence (SRGBV) for the Education Sector', UNESCO, 2014.

- ^ a b Crozier, W. R.; Skliopidou, E. (2002). "Adult Recollections of Name-calling at School". Educational Psychology. 22 (1): 113–124. doi:10.1080/01443410120101288. S2CID 144840572.

- ^ a b c Phoenix, A.; Frosh, S.; Pattman, R. (2003). "Producing Contradictory Masculine Subject Positions: Narratives of Threat, Homophobia and Bullying in 11-14 Year Old Boys". Journal of Social Issues. 59 (1): 179–195. doi:10.1111/1540-4560.t01-1-00011.

- ^ a b c d e Smith, G. W. (1998). "The Ideology of "Fag": The School Experience of Gay Students". The Sociological Quarterly. 39 (2): 309–335. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.1998.tb00506.x.

- ^ Kimmel, M. (2010). Masculinity as Homophobia, Fear, Shame and Silence in the Construction of Gender Identity. In M. S. Kimmel & A. L. Ferber (Eds.), Privilege, A Reader (pp.107-131). Boulder: Westview Press

- ^ a b Herek, G. M. (1986). "On Heterosexual Masculinity, Some Psychical Consequences of the Social Construction of Gender and Sexuality". American Behavioral Scientist. 29 (5): 563–577. doi:10.1177/000276486029005005. S2CID 143684814.

- ^ Glew, G. M.; Fan, M.; Katon, W.; Rivara, F. P.; Kernic, M. A. (2005). "Bullying, Psychosocial Adjustment, and Academic Performance in Elementary School". Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 159 (11): 1026–1031. doi:10.1001/archpedi.159.11.1026. PMID 16275791.

- ^ a b Roth, D. A.; Coles, M. E.; Heimberg, R. G. (2002). "The relationship between memories for childhood teasing and anxiety and depression in adulthood". Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 16 (2): 149–164. doi:10.1016/s0887-6185(01)00096-2. PMID 12194541.

- ^ Russell, S. T.; Ryan, C.; Toomey, R. B.; Diaz, R. M.; Sanchez, J. (2011). "Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Adolescent School Victimization: Implications for Young Adult Health and Adjustment". Journal of School Health. 81 (5): 223–230. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00583.x. PMID 21517860.

- ^ Rivers, I (2004). "Recollections of Bullying at School and Their Long-Term Implications for Lesbians, Gay Men and Bisexuals". Crisis. 25 (4): 169–175. doi:10.1027/0227-5910.25.4.169. PMID 15580852. S2CID 32996444.

- ^ Meyer, I. H. (1995). "Minority Stress and Mental Health in Gay Men". Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 36 (1): 38–56. doi:10.2307/2137286. JSTOR 2137286. PMID 7738327.

- ^ Sweet, Matt. "Depression and Anxiety in LGBT People: What You Need to Know" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 7, 2020. Retrieved July 18, 2017.

- ^ a b Sweet, Matt. "Depression and Anxiety in the LGBT People: What You Need to Know" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-11-07. Retrieved 2023-03-11.

- ^ "The School Report" (PDF). Stonewall. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-01-22. Retrieved 2023-03-11.

- ^ "Gay Male and Lesbian Youth Suicide" (PDF). 1989. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 14, 2011.

- ^ "Statistics". American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. Archived from the original on December 6, 2010. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- ^ "Suicide Prevention". Center for Disease Control and Prevention. February 5, 2019. Archived from the original on May 4, 2017.

- ^ Every Class in Every School Archived August 6, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Final Report on the First National Climate Survey on Homophobia, Biphobia, and Transphobia in Canadian Schools, Egale Canada

- ^ Nordgren, L. F.; Banas, K.; MacDonald, G. (2011). "Empathy Gaps for Social Pain: Why People Underestimate the Pain of Social Suffering". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 100 (1): 120–128. doi:10.1037/a0020938. PMID 21219077.

- ^ "Gay Bullying in Schools Common". BBC News. June 26, 2007.

- ^ "Homophobic bullying". stonewall.org.uk. Stonewall. Archived from the original on October 23, 2014. Retrieved December 25, 2014.

- ^ Pascoe, C. J. (2007). Dude You're a Fag, Masculinity and Sexuality in High School. Berkeley & Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press

- ^ "Mental Health American, Bullying and Gay Youth". National Mental Health Association. Archived from the original on April 14, 2012.

- ^ "How 'gay' Became Children's Insult of Choice". BBC News. 2008-03-18.

- ^ "Damilola's grieving father speaks out". BBC News. November 30, 2000.

- ^ Hopkins, Nick (November 29, 2000). "Death of a schoolboy". The Guardian.

- ^ Bennetto, Jason (November 29, 2000). "His mother told teachers he was being bullied. Now she must bury him". Independent.[dead link]

- ^ Steele, John (June 19, 2001). "Damilola's father attacks loss of values". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022.

- ^ Tatchell, Peter (January 13, 2003). "A victim of homophobia?". New Statesman.

- ^ "Nabozny v. Podlesny". Lambda Legal. Archived from the original on July 25, 2012. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- ^ Merjian, Armen H. (Fall 2009). "Henkle v. Gregory: A Landmark Struggle against Student Gay Bashing" (PDF). Cardozo Journal of Law & Gender. 16 (1): 41–64. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 29, 2014. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

- ^ Parker, Ian (February 6, 2012). "The Story of a Suicide". The New Yorker. Retrieved February 5, 2012.

- ^ "Kenneth Weishuhn, Gay Iowa Teen, Commits Suicide After Allegedly Receiving Death Threats". Huffington Post. 2012-04-17. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ^ Mulvihill, Evan (2012-04-18). "Heartbreaking Details Emerge In Suicide Of Out Iowa Teen Kenneth Weishuhn". Queerty. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ^ Nichols, James (2013-10-10). "Jadin Bell's Father, Joe Bell, Killed While Walking Cross Country For Tribute To Dead Gay Teen". Huffington Post. Retrieved March 20, 2014.

- ^ "Jadin Bell's father Joe Bell of La Grande killed by truck while walking in memory of son". Oregon Live. October 10, 2013. Retrieved March 20, 2014.

- ^ "CBS employees join the It Gets Better Project". CNET. Retrieved August 21, 2011.

- ^ a b "Adam Lambert Revamps 'Aftermath' for The Trevor Project". MTV. Archived from the original on April 13, 2011. Retrieved August 21, 2011.

- ^ a b "Dan Savage: For Gay Teens, Life 'Gets Better'". NPR.org. NPR. Retrieved August 21, 2011.

- ^ "Grupo Gay da Bahia - GGB". www.ggb.org.br. 23 August 2023.

- ^ "Grupo Gay da Bahia "premia" Dilma como inimiga número 1 dos homossexuais". Repórter Alagoas (in Portuguese). March 9, 2012. Archived from the original on May 16, 2013. Retrieved July 25, 2017.

- ^ "kit anti-homofobia: grupo Gay da Bahia dá troféu de "inimiga da causa" a presidente Dilma Rousseff". TV Recôncavo (in Portuguese). October 3, 2012. Archived from the original on April 4, 2013. Retrieved July 25, 2017.

- ^ "Bill Text - AB-537 Discrimination". leginfo.legislature.ca.gov. Retrieved 2022-03-07.

- ^ "SB3266 Text". Archived from the original on March 11, 2011.

- ^ "Implementing Rules and Regulations of Republic Act No. 10627". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Government of the Philippines. 13 December 2013. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

Further reading

- Duncan, Neil (2001). Sexual Bullying: Gender Conflict and Pupil Culture in Secondary Schools. UK: Routledge.

- Meyer, Elizabeth (2009). Gender, Bullying, and Harassment: Strategies to End Sexism and Homophobia in Schools. US: Teacher's College Press.

- Cyberbullying and the LGBT Community. US: Human Rights Campaign. Archived from the original on June 3, 2013. Retrieved December 22, 2010.

- "You Have to Be Strong to Be Gay": Bullying and Educational Attainment in LGB New Zealanders. New Zealand: Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services. 2008.

- Traversing the Margins: Intersectionalities in the Bullying of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Youth. New Zealand: Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services. 2008.

- Homophobic Bullying and Same-Sex Desire in Anglo-American Schools: An Historical Perspective. New Zealand: Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services. 2008.

- Pascoe, CJ (2007). "Dude, You're a Fag", Masculinity and Sexuality in High School. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520271487.

- Olweus, Dan (1993). Bullying at School, What We Know and What We Can Do. Blackwell. ISBN 978-0631192398.