History of Shia Islam

| Part of a series on Shia Islam |

|---|

|

|

|

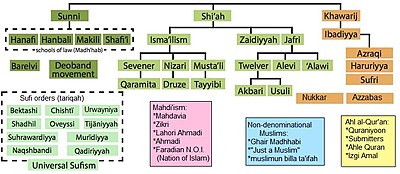

Shi‘a Islam, also known as Shi‘ite Islam or Shia, is the second largest branch of Islam after Sunni Islam. Shias adhere to the teachings of Muhammad and the religious guidance of his family (who are referred to as the Ahl al-Bayt) or his descendants known as Shia Imams. Muhammad's bloodline continues only through his daughter Fatima Zahra and cousin Ali who alongside Muhammad's grandsons comprise the Ahl al-Bayt. Thus, Shias consider Muhammad's descendants as the true source of guidance along with the teaching of Muhammad. Shia Islam, like Sunni Islam, has at times been divided into many branches; however, only three of these currently have a significant number of followers, and each of them has a separate trajectory.

From a political viewpoint the history of the Shia was in several stages. The first part was the emergence of the Shia, which starts after Muhammad's death in 632 and lasts until Battle of Karbala in 680. This part coincides with the Imamah of Ali, Hasan ibn Ali and Hussain. The second part is the differentiation and distinction of the Shia as a separate sect within the Muslim community, and the opposition of the Sunni caliphs. This part starts after the Battle of Karbala and lasts until the formation of the Shia states about 900. During this section Shi'ism divided into several branches. The third section is the period of Shia states. The first Shia state was the Idrisid dynasty (780–974) in Maghreb. Next was the Alavid dynasty (864–928) established in Mazandaran (Tabaristan), north of Iran. These dynasties were local, but they were followed by two great and powerful dynasties. The Fatimid Dynasty formed in Ifriqiya in 909, and ruled over varying areas of the Maghreb, Egypt and the Levant until 1171. The Buyid dynasty emerged in Daylaman, north of Iran, about 930 and then ruled over central and western parts of Iran and Iraq until 1048. As a result, the period from the mid-10th to the mid-11th century is often known as the "Shi'a Century" of Islam. In Yemen, Imams of various dynasties usually of the Zaidi sect established a theocratic political structure that survived from 897 until 1962. Iran, formerly of Sunni majority region underwent a process of forced conversion to Shia Islam under the Saffavids between the 16th and 18th century. The process also ensured the dominance of the Twelver sect within Shiism over the Zaidiyyah and sects of Isma'ilism in the modern day.[1][2][3][4]

From Saqifa to Karbala

Muhammad began preaching Islam at Mecca before migrating to Medina, from where he united the tribes of Arabia into a singular Arab Muslim religious polity. With Muhammad's death in 632, disagreement broke out over who would succeed him as leader of the Muslim community. While Ali ibn Abi Talib, his cousin and son-in-law, and the rest of Muhammad's close family were washing his body for burial, the tribal leaders of Mecca and Medina held a secret gathering at Saqifah to decide who would succeed Muhammad as head of the Muslim state, disregarding what the earliest Muslims, the Muhajirun, regarded as Muhammad's appointment of Ali as his successor at Ghadir Khumm. Umar ibn al-Khattab, a companion of Muhammad and the first person to congratulate Ali on event of Ghadeer, nominated Abu Bakr. Others, after initial refusal and bickering, settled on Abu Bakr who was made the first caliph. This choice was disputed by Muhammad's earliest companions, who held that Ali had been designated his successor. According to Sunni accounts, Muhammad died without having appointed a successor, and with a need for leadership, they gathered and voted for the position of caliph. Shi'a accounts differ by asserting that Muhammad had designated Ali as his successor on a number of occasions, including on his death bed. Ali was supported by Muhammad's family and the majority of the Muhajirun, the initial Muslims, and was opposed by the tribal leaders of Arabia who included Muhammad's initial enemies, including, naturally, the Banu Umayya.[5] Even during the time of Muhammad, there were signs of split among the companions with Salman al-Farsi, Abu Dharr al-Ghifari, Miqdad, and Ammar ibn Yasir amongst the most vehement and loyal supporters of ʿAlī.[6][7] Abu Bakr's election was followed by a raid on Ali's house led by Umar and Khalid ibn al-Walid (see Umar at Fatimah's house). [8]

The succession to Muhammad is an extremely contentious issue. Muslims ultimately divided into two branches based on their political attitude towards this issue, which forms the primary theological barrier between the two major divisions of Muslims: Sunni and Shi'a, with the latter following Ali as the successor to Muhammad. The two groups also disagree on Ali's attitude towards Abu Bakr, and the two caliphs who succeeded him: Umar (or `Umar ibn al-Khattāb) and Uthman or (‘Uthmān ibn ‘Affān). Sunnis tend to stress Ali's acceptance and support of their rule, while the Shi'a claims that he distanced himself from them, and that he was being kept from fulfilling the religious duty that Muhammad had appointed to him. The Sunni Muslims say that if Ali was the rightful successor as ordained by God Himself, then it would have been his duty as the leader of the Muslim nation to make war with these people (Abu Bakr, Umar, and Uthman) until Ali established the decree. Shia claim, however, that Ali did not fight Abu Bakr, Umar or Uthman, because firstly he did not have the military strength and if he decided to, it would have caused a civil war amongst the Muslims, which was still a nascent community throughout the Arab world.[9]

The event of Dhul Asheera

During the revelation of Ash-Shu'ara, the twenty-sixth Surah of the Quran, in c. 617 CE,[10] Muhammad is said to have received instructions to warn his family members against adhering to their pre-Islamic religious practices. There are differing accounts of Muhammad's attempt to do this, with one version stating that he had invited his relatives to a meal (later termed the Feast of Dhul Asheera), during which he gave the pronouncement.[11] According to Ibn Ishaq, it consisted of the following speech:

Allah has commanded me to invite you to His religion by saying: And warn thy nearest kinsfolk. I, therefore, warn you, and call upon you to testify that there is no god but Allah, and that I am His messenger. O ye sons of Abdul Muttalib, no one ever came to you before with anything better than what I have brought to you. By accepting it, your welfare will be assured in this world and in the Hereafter. Who among you will support me in carrying out this momentous duty? Who will share the burden of this work with me? Who will respond to my call? Who will become my vicegerent, my deputy and my wazir?[12]

Among those gathered, only ʿAlī offered his consent. Some sources, such as the Musnad Ahmad ibn Hanbal, do not record Muhammad's reaction to this, though Ibn Ishaq continues that he then declared ʿAlī to be his brother, heir and successor.[13] In another narration, when Muhammad accepted ʿAlī's offer, he "threw up his arms around the generous youth, and pressed him to his bosom" and said, "Behold my brother, my vizir, my vicegerent ... let all listen to his words, and obey him".[14] The direct appointment of ʿAlī as heir in this version is notable in that it alleges that his right to succession was established at the very beginning of Muhammad's prophetic activity. The association with the revelation of a Quranic verse also serves the purpose of providing the nomination with authenticity as well as a divine authorization.[15]

Event of Ghadir Khumm

The hadith report of Ghadir Khumm has many different variations and is transmitted by both Sunnī and Shīʿa sources. The narrations generally state that in March 632, Muhammad, while returning from his Farewell Pilgrimage alongside a large number of followers and companions, stopped at the oasis of Ghadir Khumm. There, he took ʿAlī's hand and addressed the gathering. The point of contention between different sects arises when Muhammad, whilst giving his speech, gave the proclamation "Anyone who has me as his mawla, has ʿAlī as his mawla".[16][17][18][19] Some versions add the additional sentence "O God, befriend the friend of ʿAlī and be the enemy of his enemy".[20]

Mawla has a number of meanings in Arabic, with interpretations of Muhammad's use here being split along sectarian lines between the Sunnī and Shīʿa Muslims. Among the former group, the word is translated as "friend" or "one who is loyal/close" and that Muhammad was advocating that ʿAlī was deserving of friendship and respect. Conversely, Shīʿa Muslims tend to view the meaning as being "master" or "ruler",[citation needed] and that the statement was a clear designation of ʿAlī being Muhammad's appointed successor.[16][21][22][23] Shīʿa sources also record further details of the event, such as stating that those present congratulated ʿAlī and acclaimed him as Amir al-Mu'minin ("commander of the believers").[20]

Caliphate of ʿAlī

When Muhammad died in 632 CE, ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib and Muhammad's closest relatives made the funeral arrangements. While they were preparing his body, Abū Bakr, ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb, and Abu Ubaidah ibn al Jarrah met with the leaders of Medina and elected Abū Bakr as caliph. ʿAlī did not accept the caliphate of Abū Bakr and refused to pledge allegiance to him. This is indicated in a hadith report which both Sunnī and Shīʿa Muslims regard as sahih (authentic).

Ibn Qutaybah, a 9th-century Sunnī Islamic scholar narrates of ʿAlī:

I am the servant of God and the brother of the Messenger of God. I am thus more worthy of this office than you. I shall not give allegiance to you [Abu Bakr & Umar] when it is more proper for you to give bayʼah to me. You have seized this office from the Ansar using your tribal relationship to the Prophet as an argument against them. Would you then seize this office from us, the ahl al-bayt by force? Did you not claim before the Ansar that you were more worthy than they of the caliphate because Muhammad came from among you (but Muhammad was never from Abu Bakr's family)—and thus they gave you leadership and surrendered command? I now contend against you with the same argument…It is we who are more worthy of the Messenger of God, living or dead. Give us our due right if you truly have faith in God, or else bear the charge of wilfully doing wrong... Umar, I will not yield to your commands: I shall not pledge loyalty to him.' Ultimately Abu Bakr said, "O 'Ali! If you do not desire to give your bay'ah, I am not going to force you for the same.[citation needed]

ʿAlī's wife and daughter of Muhammad, Fāṭimah, refused to pledge allegiance to Abū Bakr and remained angry with him until she died due to the issues of Fadak, the inheritance from her father, and the situation of ʿUmar at Fāṭimah's house; this is stated in various Sunnī hadith collections, including Sahih al-Bukhari and Sahih Muslim. Fāṭimah never pledged allegiance to Abū Bakr; neither did she acknowledge or accept his claim to the caliphate.[24] Almost all members of Banu Hashim, the Quraysh tribe to which Muhammad belonged, and many of his closest companions (the ṣaḥāba) had supported ʿAlī's cause after the death of Muhammad, whilst others supported Abū Bakr.[25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33]

It was not until the murder of the third rāshidūn caliph, ʿUthmān (657 CE), that the Muslims of Medina in desperation invited ʿAlī to become the fourth caliph as the last source,[34] and he established his capital in Kufa (present-day Iraq).[36] ʿAlī's rule over the early Muslim community was often contested, and wars were waged against him. As a result, he had to struggle to maintain his power against the groups who betrayed him after giving allegiance to his succession, or those who wished to take his position. This dispute eventually led to the First Fitna, which was the first major civil war between Muslims within the early Islamic empire. The First Fitna began as a series of revolts fought against ʿAlī, caused by the assassination of his political predecessor, ʿUthmān. While the rebels had previously affirmed the legitimacy of ʿAlī's khilafāʾ (caliphate), they later turned against ʿAlī and fought him.[34] ʿAlī ruled from 656 CE to 661 CE,[34] when he was assassinated[35] while prostrating in prayer (sujud). ʿAlī's main rival, Muawiyah, then claimed the caliphate.[37]

The connection between the Indus Valley and Shīʿa Islam was established through the early Muslim conquests. According to Derryl N. Maclean, a link between the Sindh region and Shīʿas or proto-Shīʿas can be traced to Hakim ibn Jabalah al-Abdi, a companion of Muhammad, who traveled across the Sindh to Makran in the year 649 CE, and presented a report on the area to the caliph. He supported ʿAlī, and died in the Battle of the Camel alongside Sindhi Jats.[38] He was also a poet and few couplets of his poem in praise of ʿAlī have survived, as reported in Chachnama:[39]

"Oh Ali, owing to your alliance (with the prophet) you are truly of high birth, and your example is great, and you are wise and excellent, and your advent has made your age an age of generosity and kindness and brotherly love".[40]

During the caliphate of ʿAlī, many Jats came under the influence of Shīʿa Islam.[41] Harith ibn Murrah Al-abdi and Sayfi ibn Fil' al-Shaybani, both officers of ʿAlī's army, attacked Sindhi bandits and chased them to Al-Qiqan (present-day Quetta) in the year 658 CE.[42] Sayfi was one of the seven Shīʿa Muslims who were beheaded alongside Hujr ibn Adi al-Kindi[43] in 660 CE, near Damascus.

Ḥasan ibn ʿAlī

Upon the death of ʿAlī, his elder son Ḥasan became leader of the Muslims of Kufa, and after a series of skirmishes between the Kufa Muslims and the army of Muawiyah, Ḥasan agreed to cede the caliphate to Muawiyah and maintain peace among Muslims upon certain conditions:[44][45]

- The enforced public cursing of ʿAlī, e.g. during prayers, should be abandoned

- Muawiyah should not use tax money for his own private needs

- There should be peace, and followers of Ḥasan should be given security and their rights

- Muawiyah will never adopt the title of Amir al-Mu'minin ("commander of the believers")

- Muawiyah will not nominate any successor

Ḥasan then retired to Medina, where in 670 CE he was poisoned by his wife Ja'da bint al-Ash'ath ibn Qays, after being secretly contacted by Muawiyah who wished to pass the caliphate to his own son Yazid and saw Ḥasan as an obstacle.[46]

Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī

Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī, ʿAlī's younger son and brother to Ḥasan, initially resisted calls to lead the Muslims against Muawiyah and reclaim the caliphate. In 680 CE, Muawiyah died and passed the caliphate to his son Yazid, and breaking the treaty with Ḥasan ibn ʿAlī. Yazid asked Husayn to swear allegiance (bay'ah) to him. ʿAlī's faction, having expected the caliphate to return to ʿAlī's line upon Muawiyah's death, saw this as a betrayal of the peace treaty and so Ḥusayn rejected this request for allegiance. There was a groundswell of support in Kufa for Ḥusayn to return there and take his position as caliph and Imam, so Ḥusayn collected his family and followers in Medina and set off for Kufa. En route to Kufa, he was blocked by an army of Yazid's men, which included people from Kufa, near Karbala (modern Iraq); Ḥusayn and approximately 72 of his family members and followers were killed in the Battle of Karbala.

Shīʿa Muslims regard Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī as a martyr (shahid), and count him as an Imam from the Ahl al-Bayt. They view Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī as the defender of Islam from annihilation at the hands of Yazid I. Ḥusayn is the last Imam following ʿAlī mutually recognized by all branches of Shīʿa Islam.[47] The Battle of Karbala and martyrdom of Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī is often cited as the definitive separation between the Shīʿa and Sunnī sects of Islam, and is commemorated each year by Shīʿa Muslims on the Day of Ashura.

Differentiation and distinction

Shia Islam and Sunnism split in the aftermath of the death of Muhammad based on the politics of the early caliphs. Due to the Shi'a belief that Ali should have been the first caliph, the three caliphs that preceded him, Abu Bakr, Umar, and Usman, were considered illegitimate usurpers. Because of this, any hadith that were narrated by these three caliphs (or any of their supporters) were not accepted by Shi'a hadith collectors.

Due to this, the number of hadith accepted by Shi'a is far less than the hadith accepted by Sunnis, with many of the non-accepted hadith being ones that had to deal with integral aspects of Islam, such as prayer and marriage. In the absence of a clear hadith for a situation, the Shi'a prefer the sayings and actions of the Imams (Muhammad's family members) on a similar level as the hadith of Muhammad himself over other ways, which in turn led to the theological elevation of the Imams as being infallible.[48][49]

Division into branches

Ancestors and the family tree

Twelvers history

Imams era

Occultation era

Ismaili history

Old Da'vat

New Da'vat

Zaidiyya history

Other sects

Alevis

Alawism

Shia empires

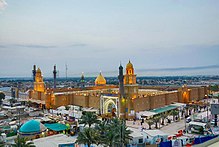

The following pictures are examples of some of the Shia Islamic empires through history:

- Buyid empire in 970

- Extent of Shia rule under the Fatimids

- Extent of Shia rule under the Uqaylids

- Extent of Shia rule under the Safavid dynasty

Notes

- ^ Arshin Adib-Moghaddam (2017), Psycho-nationalism, Cambridge University Press, p. 40, ISBN 9781108423076,

Shah Ismail pursued a relentless campaign of forced conversion of the majority Sunni population in Iran to (Twelver) Shia Islam...

- ^ Conversion and Islam in the Early Modern Mediterranean: The Lure of the Other, Routledge, 2017, p. 92, ISBN 9781317159780

- ^ Islam: Art and Architecture, Könemann, 2004, p. 501,

Shah persecuted the philosophers, mystics, and Sufis who had been promoted by his grandfather, and unleashed fanatical campaigns of forcible conversion on Sunnis, Jews, Christians and other religious minorities

- ^ Melissa L. Rossi (2008), What Every American Should Know about the Middle East, Penguin, ISBN 9780452289598,

Forced conversion in the Safavid Empire made Persia for the first time dominantly Shia and left a lasting mark: Persia, now Iran, has been dominantly Shia ever since, and for centuries the only country to have a ruling Shia majority.

- ^ Chirri, Mohammad (1982). The Brother of the Prophet Mohammad. Islamic Center of America, Detroit, MI. Alibris ID 8126171834.

- ^ Ali, Abbas, ed. (12 November 2013). "Respecting the Righteous Companions". A Shi'ite Encyclopedia. Ahlul Bayt Digital Islamic Library Project. Archived from the original on 3 June 2020 – via al-islam.org.

- ^ Ja'fariyan, Rasul (2014). "Umars Caliphate". History of the Caliphs. Lulu.com. p. 290. ISBN 978-1-312-54108-5.

Abu Hatin al-Razi says, "It is the appellation of those who were attached to Ali during the lifetime of the Messenger of Allah, such as Salman, Abu Dharr Ghifari, Miqdad ibn al-Aswad and Ammar ibn Yasir and others. Concerning these four, the Messenger of Allah had declared, 'The paradise is eager for four men: Salman, Abu Dharr, Miqdad, and Ammar.'"

[permanent dead link]- Rasul Ja'fariyan (1996). "Shi'ism and Its Types During the Early Centuries". Al Seraj. Archived from the original on 3 June 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ See:

- Holt (1977a), p.57

- Lapidus (2002), p.32

- Madelung (1996), p.43

- Tabatabaei (1979), p.30–50

- ^ Sahih Bukhari

- ^ Zwettler, Michael (1990). "A Mantic Manifesto: The Sura of "The Poets" and the Qur'anic Foundations of Prophetic Authority". Poetry and Prophecy: The Beginnings of a Literary Tradition. Cornell University Press. p. 84. ISBN 0-8014-9568-7.

- ^ Rubin, Uri (1995). The Eye of the Beholder: The life of Muhammad as viewed by the early Muslims. Princeton, New Jersey: The Darwin Press Inc. pp. 135–138. ISBN 978-0-87850-110-6.

- ^ Razwy, Sayed Ali Asgher. A Restatement of the History of Islam & Muslims. pp. 54–55.

- ^ Rubin (1995, p. 137)

- ^ Irving, Washington (1868), Mahomet and His Successors, vol. I, New York: G. P. Putnam and Son, p. 71

- ^ Rubin (1995, pp. 136–137)

- ^ a b Foody, Kathleen (September 2015). Jain, Andrea R. (ed.). "Interiorizing Islam: Religious Experience and State Oversight in the Islamic Republic of Iran". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 83 (3). Oxford: Oxford University Press on behalf of the American Academy of Religion: 599–623. doi:10.1093/jaarel/lfv029. eISSN 1477-4585. ISSN 0002-7189. JSTOR 24488178. LCCN sc76000837. OCLC 1479270.

For Shiʿi Muslims, Muhammad not only designated ʿAlī as his friend, but appointed him as his successor—as the "lord" or "master" of the new Muslim community. ʿAlī and his descendants would become known as the Imams, divinely guided leaders of the Shiʿi communities, sinless, and granted special insight into the Qurʾanic text. The theology of the Imams that developed over the next several centuries made little distinction between the authority of the Imams to politically lead the Muslim community and their spiritual prowess; quite to the contrary, their right to political leadership was grounded in their special spiritual insight. While in theory, the only just ruler of the Muslim community was the Imam, the Imams were politically marginal after the first generation. In practice, Shiʿi Muslims negotiated varied approaches to both interpretative authority over Islamic texts and governance of the community, both during the lifetimes of the Imams themselves and even more so following the disappearance of the twelfth and final Imam in the ninth century.

- ^ Newman, Andrew J. Shiʿi. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ^ Esposito, John. "What Everyone Needs to Know about Islam". Oxford University Press, 2002 | ISBN 978-0-19-515713-0. p. 40

- ^ "From the article on Shii Islam in Oxford Islamic Studies Online". Oxfordislamicstudies.com. Archived from the original on 28 May 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2011.

- ^ a b Amir-Moezzi, Mohammad Ali (2014). "Ghadīr Khumm". In Kate Fleet; Gundrun Krämer; Denis Matringe; John Nawas; Everett Rowson (eds.). Ghadīr Khumm. Encyclopaedia of Islam Three. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_27419.

- ^ Olawuyi, Toyib (2014). On the Khilafah of Ali over Abu Bakr. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-4928-5884-3. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016.

- ^ "The Shura Principle in Islam – by Sadek Sulaiman". www.alhewar.com. Archived from the original on 27 July 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ "Sunnis and Shia: Islam's ancient schism". BBC News. 2016-01-04. Retrieved 2021-08-14.

- ^ "After the death of Allah 's Apostle Fatima the daughter of Allah's Apostle asked Abu Bakr As-Siddiq to give her, her share of inheritance from what Allah's Apostle had (p. 1) – Sunnah.com – Sayings and Teachings of Prophet Muhammad (صلى الله عليه و سلم)". Archived from the original on 10 October 2017.

- ^ "Lesson 8: The Shiʻah among the Companions {sahabah}". Al-Islam.org. February 2013. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017.

- ^ "Chapter 3: State of Affairs in Saqifah after the Death of the Prophet". Al-Islam.org. 21 April 2016. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017.

- ^ "Did Imam Ali Give Allegiance to Abu Bakr?". Islamic Insights. 8 December 2009. Archived from the original on 28 June 2017.

- ^ Riz̤vī, Sayyid Sa'eed Ak̲h̲tar. Slavery: From Islamic & Christian Perspectives. Richmond, British Columbia: Vancouver Islamic Educational Foundation, 1988. Print. ISBN 0-920675-07-7 pp. 35–36

- ^ "The Succession to Muhammad" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 July 2017. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- ^ Shaikh, Asif. Sahaba: The Companion. n.p., n.d. Print. pp. 42–45

- ^ Peshawar Nights

- ^ A list composed of sources such as Ibn Hajar Asqalani and Baladhuri, each in his Ta'rikh, Muhammad Bin Khawind Shah in his Rauzatu's-Safa, Ibn Abdu'l-Birr in his Isti'ab

- ^ Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari, vol. 3, p. 208; Ayoub, 2003, 21

- ^ a b c d Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions, Wendy Doniger, Consulting Editor, Merriam-Webster, Inc., Springfield, MA 1999, ISBN 0-87779-044-2, LoC: BL31.M47 1999, p. 525

- ^ a b "Esposito, John. "What Everyone Needs to Know about Islam" Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0-19-515713-0. p. 46

- ^ The New Encyclopædia Britannica, 15th ed., Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 1998, ISBN 0-85229-663-0, Vol. 10, p. 738

- ^ The New Encyclopædia Britannica, 15th ed., Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 1998, ISBN 0-85229-663-0, Vol. 10, p. tid738

- ^ M. Ishaq, "Hakim Bin Jabala – An Heroic Personality of Early Islam", Journal of the Pakistan Historical Society, pp. 145–150, (April 1955).

- ^ Derryl N. Maclean," Religion and Society in Arab Sind", p. 126, Brill, (1989) ISBN 90-04-08551-3.

- ^ Mirza Kalichbeg Fredunbeg, "The Chachnama", p. 43, The Commissioner's Press, Karachi (1900).

- ^ Ibn Athir, Vol. 3, pp. 45–46, 381, as cited in: S. A. N. Rezavi, "The Shia Muslims", in History of Science, Philosophy and Culture in Indian Civilization, Vol. 2, Part. 2: "Religious Movements and Institutions in Medieval India", Chapter 13, Oxford University Press (2006).

- ^ Ibn Sa'd, 8:346. The raid is noted by Baâdhurî, "fatooh al-Baldan" p. 432, and Ibn Khayyât, Ta'rîkh, 1:173, 183–184, as cited in: Derryl N. Maclean," Religion and Society in Arab Sind", p. 126, BRILL, (1989) ISBN 90-04-08551-3.

- ^ Tabarî, 2:129, 143, 147, as cited in: Derryl N. Maclean," Religion and Society in Arab Sind", p. 126, Brill, (1989) ISBN 90-04-08551-3.

- ^ ""Solhe Emam Hassan"-Imam Hassan Sets Peace". Archived from the original on 11 March 2013.

- ^ تهذیب التهذیب. p. 271.

- ^ Madelung, Wilfred (2003). "Ḥasan b. ʿAli b. Abi Ṭāleb". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- ^ Discovering Islam: making sense of Muslim history and society (2002) Akbar S. Ahmed

- ^ Alkhateeb, Firas (2014). Lost Islamic History. London: Hurst Publishers. p. 85. ISBN 9781849043977.

- ^ Ochsenwald, William (2004). The Middle East: A History. Boston: McGraw Hill. p. 90. ISBN 0072442336.

- ^ "Mapping the Global Muslim Population: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Muslim Population". Pew Research Center. October 7, 2009. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

Of the total Muslim population, 11-12% are Shia Muslims and 87-88% are Sunni Muslims.

- ^ "Religions". CIA World Factbook. Archived from the original on June 13, 2007.

- ^ "Mapping the Global Muslim Population". Pew Research Center. 7 October 2009.

See also

References

- Holt, P. M.; Bernard Lewis (1977a). Cambridge History of Islam, Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521291364.

- Lapidus, Ira (2002). A History of Islamic Societies (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521779333.

- Madelung, Wilferd (1996). The Succession to Muhammad: A Study of the Early Caliphate. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521646960.

- Tabatabae, Sayyid Mohammad Hosayn (1979). Shi'ite Islam. Seyyed Hossein Nasr (trans.). Suny press. ISBN 0-87395-272-3.