Hindenburg Programme

The Hindenburg Programme of August 1916 is the name given to the armaments and economic policy begun in late 1916 by the Third Oberste Heeresleitung (OHL, headquarters of the German General Staff), Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg and General Erich Ludendorff. The two were appointed after the sacking of General Erich von Falkenhayn on 28 August 1916 and intended to double German industrial production, to greatly increase the output of munitions and weapons.

Background

Third OHL

On 29 August 1916, Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg and General Erich Ludendorff were appointed as heads of Oberste Heeresleitung (OHL, German General Staff) of the German army, after the sacking of General Erich von Falkenhayn, who had commanded the armies of Germany since September 1914. The new commanders, who became known as the Third OHL, had spent two years in command of Oberbefehlshaber der gesamten Deutschen Streitkräfte im Osten (Ober Ost, Supreme Commander of All German Forces in the East) on the German section of the Eastern Front. Hindenburg and Ludendorff had demanded reinforcements from Falkenhayn to fight a decisive campaign against Russia and intrigued against Falkenhayn over his refusals. Falkenhayn held that decisive military victory against Russia was impossible and that the Western Front was the decisive theatre of the war. Soon after taking over from Falkenhayn, Hindenburg and Ludendorff had no choice but to recognise the wisdom of the emphasis given by Falkenhayn to the Western Front, despite the crisis in the east caused by the Brusilov Offensive (4 June – 20 September) and the Romanian declaration of war on 28 August.[1]

Prelude

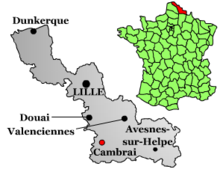

Cambrai conference

On 8 September, Hindenburg and Ludendorff held a conference at Cambrai with the chiefs of staff of the armies of the Westheer (army of the west) as part of a tour of inspection of the Western Front. Both men were dismayed at the nature of trench warfare that they found, in such contrast to the conditions on the Eastern Front and the dilapidated state of the Westheer. The Battle of Verdun and the Battle of the Somme had been extraordinarily costly; on the Somme, 122,908 German casualties had been suffered from 24 June to 28 August. The battle had required the use of 29 divisions and by September, one division each day had to be withdrawn and replaced by a fresh one. The Chief of Staff of the new Heeresgruppe Deutscher Kronprinz (Army Group German Crown Prince) reported that conditions at Verdun were little better and that the recruit depots behind the army group front could supply only 50–60 percent of the casualty replacements needed. From July to August the Westheer had fired the equivalent of 587 trainloads of field gun ammunition, against the receipt of only 470 from Germany; the munitions shortage was worsening.[2][a]

The 1st Army, on the north side of the Somme, reported on 28 August that

The complications of the entire battle lay only in part with the superiority in number of enemy divisions (12 or 13 enemy against eight German on the battlefield) for our infantry feel completely the superiority of the English and French in close battle. The most difficult factor in the battle is the enemy's superiority in munitions. This allows their artillery, which is excellently supported by aircraft, to level our trenches and to wear down our infantry systematically.... The destruction of our positions is so thorough that our foremost line merely consists of occupied shell-holes.

It was known in Germany that the British had introduced the Military Service Act 1916 (conscription) on 27 January 1916 and that despite the huge losses on the Somme, there would be no shortage of reinforcements. At the end of August, German military intelligence calculated that of the 58 British divisions in France, 18 were fresh. The French manpower situation was not as buoyant but by combing out rear areas and recruiting more troops from the colonies, the French could replace losses until the 1918 conscription class became available in the summer of 1917. Of the 110 French divisions in France, 16 were in reserve and another 10–11 divisions could be obtained by swapping tired units for fresh ones on quiet parts of the front.[3]

Ludendorff admitted privately to Generalleutnant (Lieutenant-General) Hermann von Kuhl, the Chief of Staff of Heeresgruppe Kronprinz Rupprecht von Bayern (Army Group Rupprecht of Bavaria) who wrote in his diary that

I spoke...with Ludendorff alone (about the overall situation). We were in agreement that a large-scale, positive outcome is now no longer possible. We can only hold on and take the best opportunity for peace. We made too many serious errors this year.

— 8 September 1916[4]

On 29 August, Hindenburg and Ludendorff reorganised the army groups on the Western Front, by incorporating all but the 4th Army in Flanders into the army group structure on the active part of the Western Front. The administrative reorganisation eased the distribution of men and equipment, yet made no difference to the lack of numbers and to the growing Franco-British superiority in weapons and ammunition. New divisions were needed and the manpower for them and replacements for the losses of 1916 had to be found. The superiority in manpower enjoyed by the Entente and its allies could not be surpassed but Hindenburg and Ludendorff drew on ideas from Oberstleutnant (Lieutenant-Colonel) Max Bauer of the Operations Section at OHL, the supreme headquarters in Mézières, for a further industrial mobilisation, to equip the army for the Materialschlacht (battle of equipment/battle of attrition) being inflicted on it in France, which would only intensify in 1917.[5]

Hindenburg Programme

Bureaucracy

Following the adoption of the programme, the main administrative novelty of the third OHL was the Kriegsamt (Supreme War Office), founded on 1 November 1916, with General Wilhelm Groener, a railway expert, as the head. The new body was intended to by-pass the War Ministry as well as create the structure of a command economy, with a militaristic organisation intended to facilitate management and a subordinate level of six departments organised along bureaucratic lines.[6]

Army

Hindenburg and Ludendorff demanded domestic changes to complement their changes of strategy. German workers were to be subjected to a Gesetz über den vaterländischen Hilfsdienst (Hilfsdienstgesetz Auxiliary Services Law) which from November 1916, made all Germans from 16 to 50 years old subject to compulsory service.[7] The new programme was intended to treble artillery and machine-gun output and double munitions and trench mortar production. Expansion of the German Army and output of war materials caused increased competition for manpower by the army and industry. In early 1916, the German Army had 900,000 men in recruit depots and another 300,000 due in March, when the 1897 class of conscripts was called up. The army was so flush with men that plans were made to demobilise older Landwehr classes and in the summer, Falkenhayn ordered the raising of another 18 divisions, for an army of 175 divisions. The costly battles at Verdun and the Somme had been much more demanding on German divisions and they had to be relieved after only a few days in the front line, lasting about 14 days on the Somme. A larger number of divisions might reduce the strain on the Westheer and realise a surplus for offensives on other fronts. Hindenburg and Ludendorff ordered the creation of another 22 divisions, to have an army of 179 divisions by early 1917.[8]

The men for the divisions created by Falkenhayn had come from reducing square divisions with four infantry regiments to triangular divisions with three, rather than a net increase in the number of men in the army. Troops for the extra divisions of the expansion ordered by Hindenburg and Ludendorff could be found by combing out rear-area units but most would have to be drawn from the pool of replacements, which had been depleted by the losses of 1916. Although new classes of conscripts would top up the pool of replacements, keeping units up to strength would become much more difficult once the pool had to maintain a larger number of divisions. By calling up the 1898 class of recruits early in November 1916, the pool was increased to 763,000 men in February 1917 but the larger army would become a wasting asset. Ernst von Wrisberg, Abteilungschef of the kaiserlicher Oberst und Landsknechtsführer (head of the Prussian Ministry of War section responsible for raising new units), had grave doubts about the wisdom of expanding the army but was over-ruled by Ludendorff.[8]

Ammunition

The German Army had begun 1916 equally well provided for in artillery and ammunition, massing 8.5 million field and 2.7 million heavy artillery shells for the beginning of the Battle of Verdun. Four million rounds were fired in the first fortnight and the 5th Army needed about 34 ammunition trains a day to replace consumption. The Battle of the Somme further reduced the German reserve of ammunition and when the infantry was forced out of the front position, the need for Sperrfeuer (defensive barrages), to compensate for the lack of obstacles, increased. Before the war and the Allied naval Blockade of Germany, nitrates for explosives manufacture had been imported from Chile. Production of propellants could continue only because of the industrialisation of the Haber process for the synthesis of nitrates from atmospheric nitrogen but this took time to achieve.[9] Under Falkenhayn, the procurement of ammunition and artillery had been based on the output of propellants, since the manufacture of ammunition without sufficient propellants and explosive fillings was pointless. Hindenburg and Ludendorff wanted firepower to replace manpower and ignored the principle of matching means and ends.[10]

Explosives

To meet existing demand and to feed new weapons, Hindenburg and Ludendorff wanted a big increase in propellant output to 12,000 t (12,000 long tons) a month. In July 1916, the output target had been raised from 8,000–10,000 t (7,900–9,800 long tons) which was expected to cover existing demand and the extra 2,000 t (2,000 long tons) of output demanded by Hindenburg and Ludendorff could never match the doubling and trebling of artillery, machine-guns and trench mortars. The industrial mobilisation needed to fulfil the Hindenburg Programme increased demand for skilled workers, Zurückgestellte (recalled from the army) or exempted from conscription. The number of Zurückgestellte increased from 1.2 million men, of whom 740,000 were deemed kriegsverwendungsfähig (kv, fit for front line service), at the end of 1916 to 1.64 million men in October 1917 and more than two million by November, 1.16 million being kv. The demands of the Hindenburg Programme exacerbated the manpower crisis and constraints on the availability of raw materials meant that targets were not met.[11]

War economy

The Hindenburg Programme was provided with a legal basis in the Auxiliary Service Law, implemented on 6 December.[7] The German Army returned 125,000 skilled workers to the war economy and exempted 800,000 workers from conscription from September 1916 to July 1917.[12] Steel production in February 1917 was 252,000 long tons (256,000 t) short of expectations and explosives production was 1,100 long tons (1,100 t) below the target, which added to the pressure on Ludendorff to retreat to the Hindenburg Line.[13] Despite the shortfalls, by the summer of 1917, the Westheer artillery park had increased from 5,300 to 6,700 field guns and from 3,700 to 4,300 heavy guns, many being newer models of superior performance. Machine-gun output enabled each division to have 54 heavy and 108 light machine-guns and for the number of Maschinengewehr-Scharfschützen-Abteilungen (MGA, machine-gun sharpshooter detachments) to be increased. The greater output was insufficient to equip the new divisions and existing divisions which still had two artillery brigades with two regiments each, lost a regiment and the brigade headquarters, leaving three regiments. Against the new scales of equipment, British divisions in early 1917 had 64 heavy and 192 light machine-guns and the French 88 heavy and 432 light machine-guns.[14]

Slave labour

The imposition of compulsory labour for prisoners of war and deported Belgian and Polish workers began in August 1915. Three decrees of increasing severity were issued between 15 August 1915 and 13 May 1916. On 26 October 1916, 729 people who were unemployed or "work-shy" were picked up and by the time that deportations ceased on 10 February 1917, 115 deportation operations had taken place. The hope of OHL to obtain 20,000 workers per week was not realised and only 60,847 deportations were achieved. The army took the Belgians to camps where a deliberately harsh regime was imposed to coerce the victims into signing employment contracts under duress to make them "volunteers". Conditions in the camps were so poor that in a few months, 1,316 inmates died; despite the rigours, only 13,376 Belgians capitulated, the odious treatment meted out by the Germans creating anger and bitterness, rather than docility. The Pope condemned the deportations and neutral opinion, particularly in the United States, was more outraged than at any time since the francs-tireur massacres of August 1914. Well-attended rallies were held in many cities and attempts by the US president, Woodrow Wilson, to mediate a peace deal with the combatants were a failure. US opinion became overwhelmingly pro-Entente over the winter of 1916–1917.[15]

Aftermath

Analysis

Ludwig von Mises called the Hindenburg Programme a command economy.[16] Enterprises "not important to the war economy" were closed to supply more workers.[17] In 2014, Alexander Watson wrote that the Auxiliary Service Law was drastically revised in the Reichstag by Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD), Zentrumspartei (Zentrum) and the Fortschrittliche Volkspartei (FVP) deputies, to confound the attempt by the OHL to create a command economy at the expense of the working class. Extensive concessions to the workers were included in the law, with the establishment of a committee to supervise its implementation. Hindenburg later denounced the concessions as insufficient and "positively harmful"; industrialists, looking forward to a captive workforce to exploit, were aghast at being compelled to work with workers' committees and conciliation organisations. The purpose of the law, to deny workers' mobility was thwarted and with it went the possibility of a centralised organisation of manpower. The super-profits anticipated by employers were limited by the prospect of improved pay and conditions being recognised as a valid reason to change jobs. The attempt by the third OHL to reorganise the war economy through compulsion was a failure but the law was effective in substituting workers of lesser physical fitness for those capable of military service. Concessions to organised labour were valuable in retaining the co-operation of the unions during the unrest of 1917.[18]

The German army had reached its peak of manpower in 1916 and the Hindenburg Programme had been intended to reduce the burden on the remaining men by substituting machines. In 1917, the Westheer had managed to withstand the attacks of the French and the British, while offensive operations had been conducted on the eastern and southern fronts. The coalition against Germany increased its output of war materiel even more than the increase of the Hindenburg Programme, an industrial competition that Germany could not win; the programme worsened the labour shortage in Germany. The theoretical changes in German defensive tactics had greater effect than the increase in the size of the army and the output of weapons. British attacks in 1917 were much more competent than those of 1916 but German defensive methods were adapted to negate the effect of the maturing of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). The Battle of the Somme (1 July – 18 November 1916) had cost the Westheer about 500,000 casualties and the Second Battle of the Aisne (16 April – 9 May 1917), the main part of the Nivelle Offensive, cost another 163,000. The Third Battle of Ypres (31 July – 10 November) added 217,000 German casualties.[19]

Casualties in the Third Battle of Ypres led to the average number of men in an infantry battalion falling from 750 to 640 and in October, congestion on the railway lines behind the 4th Army led to more shortages. The 4th Army had a ration strength of 800,000 men and 200,000 horses, which needed 52 trains of 35 wagons each just for daily maintenance. The change to a defence based on firepower, using the extra weapons and munitions produced by the Hindenburg Programme, needed more trains to carry ammunition to the front. On 28 July, the 4th Army fired 19 munitions trains' worth of ammunition, exceeding the record 16 trains' on the Somme. On 9 October, the 4th Army was firing 27 trains' worth per day, 18 million shells being fired during the battle. The trains had to compete for space on the railways with food supplies and troop transports, which created severe difficulties for Heeresgruppe Kronprinz Rupprecht.[20] Men, horses and fuel were taken from agricultural production for the army and munitions, which caused food shortages and food price inflation, leading to Germany coming to the verge of starvation at the close of 1918.[17]

See also

- National Economic Council (est. 1880–1881) established by Otto von Bismarck

- Total war

- Military–industrial complex

Explanatory notes

Citations

- ^ Foley 2007, p. 155.

- ^ a b c Foley 2007, p. 156.

- ^ Foley 2007, pp. 156–157.

- ^ Foley 2007, p. 157.

- ^ Foley 2007, pp. 157–158.

- ^ Watson 2015, p. 378.

- ^ a b Asprey 1994, p. 285.

- ^ a b Foley 2007, pp. 158–159.

- ^ Strachan 2001, p. 1,025.

- ^ Foley 2007, pp. 159–160.

- ^ Foley 2007, pp. 160–161.

- ^ Feldman 1992, p. 301.

- ^ Feldman 1992, p. 271.

- ^ Foley 2007, pp. 161–162.

- ^ Watson 2015, pp. 385–388.

- ^ Tooley 2014, p. 59.

- ^ a b Kennedy 1989, p. 349.

- ^ Watson 2015, pp. 383–384.

- ^ Foley 2007, p. 177.

- ^ Foley 2007, pp. 175–176.

References

Books

- Asprey, R. B. (1994) [1991]. The German High Command at War: Hindenburg and Ludendorff and the First World War (Warner Books ed.). New York: William Morrow. ISBN 978-0-7515-1038-6.

- Feldman, G. D. (1992) [1966]. Army, Industry and Labor in Germany 1914–1918 (Berg repr. ed.). Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-85496-764-3.

- Dennis, P.; Grey, G., eds. (2007). 1917: Tactics, Training and Technology. Loftus, NSW: Australian History Military Publications. ISBN 978-0-9803-7967-9.

- Foley, R. T. "The Other Side of the Wire: The German Army in 1917". In Dennis & Grey (2007).

- Kennedy, Paul (1989). The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500 to 2000. New York: Fontana. ISBN 978-0-67972-019-5 – via Archive Foundation.

- Strachan, H. (2001). The First World War: To Arms. Vol. I. Oxford: OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-926191-8.

- Watson, A. (2015) [2014]. Ring of Steel: Germany and Austria-Hungary at War, 1914–1918 (pbk. repr. Penguin ed.). New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-14-104203-9.

Journals

- Tooley, T. Hunt (2014) [1999]. "The Hindenburg Program of 1916: A Central Experiment in Wartime Planning" (PDF). The Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics. 2 (2). Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute: 51–62. doi:10.1007/s12113-999-1012-0. ISSN 1098-3708. S2CID 154532407. 4633501923. Retrieved 15 September 2017 – via www mises org library.[permanent dead link]

Further reading

- Broadberry, S.; Harrison, M. (2 August 2005). The Economics of World War I: A Comparative Quantitative Analysis (PDF) (Report). Coventry: Department of Economics, University of Warwick. WWItoronto2. Retrieved 9 December 2017 – via Warwick University.

- Hardach, G. (1987). The First World War, 1914–1918. Pelican History of World Economics in the Twentieth Century. Translated by Ross, B. (New pbk. ed.). London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-022679-9.

- Laqua, Daniel (2015). The Age of Internationalism and Belgium, 1880–1930: Peace, Progress and Prestige. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-9737-9.

- Offer, A. (1989). The First World War: An Agrarian Interpretation. London: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19821-946-0 – via Archive Foundation.

- Offit, P. A. (2017). Pandora's Lab: Seven Stories of Science Gone Wrong. Washington, DC: National Geographic. ISBN 978-1-4262-1798-2.