Hilde Benjamin

Hilde Benjamin | |

|---|---|

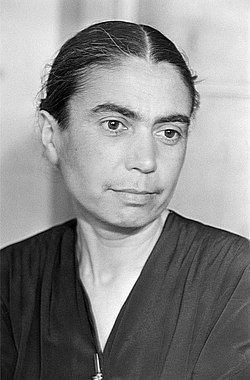

Benjamin in 1947 | |

| Minister of Justice of the German Democratic Republic | |

| In office 15 July 1953 – 14 July 1967 | |

| Chairman of the Council of Ministers | |

| Preceded by | Max Fechner |

| Succeeded by | Kurt Wünsche |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Hilde Lange 5 February 1902 Bernburg, Duchy of Anhalt, German Empire |

| Died | 18 April 1989 (aged 87) East Berlin, East Germany |

| Political party | Socialist Unity Party (1946–1989) |

| Other political affiliations | Communist Party of Germany (1927–1946) |

| Spouse | Georg Benjamin (1895–1942) |

| Alma mater | Friedrich Wilhelm University |

| Occupation |

|

Central institution membership

Other offices held

| |

Hilde Benjamin (née Lange; 5 February 1902 – 18 April 1989) was an East German judge who served as the Minister of Justice of the German Democratic Republic from 1953 to 1967.

Benjamin was a professional lawyer and member of the Communist Party of Germany before holding a number of high-ranking posts in the Socialist Unity Party (SED) and the East German government. Benjamin was appointed Vice President of the Supreme Court of the German Democratic Republic where her interpretation of the 1949 Constitution of East Germany helped the SED to prosecute dissident activity and developed a reputation as a hanging judge. Benjamin was appointed Justice Minister after the Uprising of 1953 and was responsible for the politically motivated prosecutions, including those of Erna Dorn and Ernst Jennrich.[1][2] Benjamin's career declined in the 1960s and Walter Ulbricht forced her to resign in 1967.

In his 1994 inauguration speech, German President Roman Herzog cited Benjamin as a symbol of totalitarianism and injustice, and called both her name and legacy incompatible with the German Constitution and with the rule of law.[3][4]

Early life

Hilde Lange was born on 5 February 1902 in Bernburg, Duchy of Anhalt, into a middle class and liberal-minded Protestant family.[5] She was the daughter of Heinz Lange, an engineer and clerk at a potash mine operated by Solvay near Bernberg, and his wife Adele (née Böhme).[6] She was raised in Berlin, where the family relocated when her father became head of a Solvay subsidiary in the city. Growing up in the culturally inclined liberal ambience of a middle-class family awakened in her an early interest in classical music and German literature that would stay with her throughout her life.[7] Her sister, Ruth Lange, was a record-breaking athlete in the shot put and discus throw in Germany.

In 1921, she graduated from the Fichtenberg High School in Steglitz on the south side of Berlin. She became active in the Wandervogel movement, which had its origins in Steglitz. She was among the first women to study law in Germany, attending Friedrich-Wilhelm University of Berlin, the University of Heidelberg, and the University of Hamburg from 1921 to 1924. By this time, she was a member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD).

Politics and early career

In 1926, Lange married Georg Benjamin, a socialist and pediatrician working in Wedding, a predominantly working class district of Berlin. Georg was the brother of writer Walter Benjamin and of her friend, the academic Dora Benjamin. Their son, de:Michael Benjamin, was born at the end of 1932. She quit the moderate left-wing SPD and in 1927 joined her husband in the far-left Communist Party of Germany (KPD). Because of her political convictions, she was Berufsverbot (forbidden) to practice law after the Nazi rise to power in 1933. Her husband, a communist and a Jew, was removed to Sonnenburg concentration camp directly after the Reichstag fire. Briefly jobless, she returned for a time to live with her parents along with her small son. She then obtained a position providing legal advice for the Soviet trade association in Berlin. Georg was released later in the year, though he was unable to find legal work, finding employment with the underground Berlin-Brandenburg branch of the KPD. He was arrested again in 1936, being sent to numerous prisons then Nazi concentration camps until he was finally killed at the Mauthausen in 1942. The camp's administration listed his cause of death as "Suicide by touching a high voltage power line" though he was likely beaten to death shortly after arrival. During World War II from 1939 to 1945, she was forced to work in a clothing factory.

German Democratic Republic

After the war, Benjamin was appointed head of the Personnel and Schools Department of the German Central Administration for Justice in the Soviet Occupation Zone, the predecessor to the Ministry of Justice of the German Democratic Republic. She joined the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED) in 1946, which had been formed from a merger of the KPD and SPD under pressure from the Soviet Military Administration in Germany. Following the founding of the German Democratic Republic (GDR or East Germany) in 1949, she was appointed to a number of high-ranking positions, including the Vice President of the Supreme Court of the German Democratic Republic and a member of the Volkskammer. She assisted with the controversial Waldheim Trials and presided over a series of show trials against those identified as political undesirables, such as Johann Burianek and Wolfgang Kaiser, as well as against Jehovah's Witnesses.[8]

Benjamin was instrumental in authoring the penal code and the code of penal procedure of the GDR, and played a decisive role in the reorganization of the country's legal system. Her interpretation of Article 6 of the 1949 Constitution of East Germany was highly influential, defining the vague offence of Kriegs- und Boykotthetze ("Incitement of war or to boycott") so that it could be applied to any form of political opposition to the state. This effectively gave the SED a legal route to prosecute dissident activity, at a time when the constitution lacked provisions on the subject of state security. In 1952, she imposed the death penalty for the first time in application of Article 6, in consultation with the SED leadership, in the show trial of Burianek

Minister of Justice

On 15 July 1953, Benjamin was appointed Minister of Justice of the German Democratic Republic, succeeding Max Fechner in the aftermath of the Uprising of 1953 which nearly overthrew the SED regime. Two weeks earlier, Fechner had stated in an interview to Neues Deutschland that he opposed the prosecution of workers who had taken part in the 17 June strike. The SED leadership were infuriated with Fechner, removing him as Justice Minister, denouncing him as an "enemy of the state and the party", and sent to prison. Benjamin, together with Anton Plenikowski, Ernst Melsheimer and Herbert Kern, had formed the "Justice Commission" of the SED Central Committee to secure a conviction for Fechner. Concurrently, the SED launched a purge against members considered to be moderates (mostly former SPD members) and officers of the Volkspolizei accused of "conciliatory and capitulatory behavior" towards the protesters.

Benjamin was responsible for the prosecution of those arrested during the June protests and strikes which, unlike her predecessor, she fully endorsed. She established special courts in the districts of East Germany made up of lawyers loyal to SED for this purpose. Her behavior and statements from the bench, as well as her regular use of heavy sentences, earned Benjamin the nicknames "Red Hilde", "The Red Freisler," and, "The Red Guillotine."[9] She openly cited Andrei Vyshinsky, the prosecutor in the Moscow trials during the Great Purge from 1936 to 1938.

In 1954, she was appointed to the Central Committee of the SED and would remain a member until her death.

Benjamin began to fall out of favour with East German leader Walter Ulbricht in October 1961, when Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev launched a second round of De-Stalinization. Ulbricht, under Soviet influence, criticised Benjamin and requested that she relax the political dogmatism of the legal system. She defended herself and argued that the "renunciation of Stalinist legal practices" would "open the door to Western class enemies". She did concede with relaxations and reforms in 1962 and 1963, which likely won her some favour.

In July 1967, Ulbricht forced Benjamin to resign, ostensibly for health reasons and to rejuvenate the Council of Ministers, and was replaced by Kurt Wünsche. In 1966, the Ministry for State Security had allegedly learned through interrogations of exposed CIA agent Gertrud Liebing that Benjamin belonged to a lesbian circle. This is possibly why Ulbricht removed her as Justice Minister.

From 1967 to her death, Benjamin held the chair for the history of the judiciary at the Deutsche Akademie für Staats- und Rechtswissenschaft in Potsdam-Babelsberg. She campaigned for further tightening of political criminal law and the retention of the death penalty. She died in East Berlin in April 1989. She was cremated and honoured with burial in the Pergolenweg Ehrengrab section of Berlin's Friedrichsfelde Cemetery.

Recognition

Benjamin received several awards in the GDR: in 1962 the Patriotic Order of Merit, in 1977 and 1987 the Order of Karl Marx, in 1979 the title of Meritorious Jurist of the GDR (Verdiente Juristin der DDR), and in 1982 the Star of People's Friendship.

Literature

- Andrea Feth, Hilde Benjamin – Eine Biographie, Berlin 1995 ISBN 3-87061-609-1

- Marianne Brentzel, Die Machtfrau Hilde Benjamin 1902–1989, Berlin 1997 ISBN 3-86153-139-9

- Heike Wagner, Hilde Benjamin und die Stalinisierung der DDR-Justiz, Aachen 1999 ISBN 3-8265-5855-3

- Heike Amos, Kommunistische Personalpolitik in der Justizverwaltung der SBZ/DDR (1945–1953) : Vom liberalen Justizfachmann Eugen Schiffer über den Parteifunktionär Max Fechner zur kommunistischen Juristin Hilde Benjamin, in: Gerd Bender, Recht im Sozialismus : Analysen zur Normdurchsetzung in osteuropäischen Nachkriegsgesellschaften (1944/45-1989), Frankfurt am Main 1999, Seiten 109–145. ISBN 3-465-02797-3

- Zwischen Recht und Unrecht – Lebensläufe deutscher Juristen, Justizministerium NRW 2004, S. 144–146

References

- ^ "Der Fall Erna Dorn: Wie eine Frau zur "faschistischen Rädelsführerin" erklärt und nach dem 17. Juni 1953 geköpft wurde: Die sechs Leben der "Kommandeuse"".

- ^ Kleikamp, Antonia (19 March 2014). "SED-Verbrechen: Der Gärtner war ein "geeignetes Opfer"". Die Welt.

- ^ Rudolf Wassermann:, Deutsche Richterzeitung. 1994, p. 285

- ^ Andrea Feth: Hilde Benjamin: 1902–1989, in Neue Justiz, 2/2002, p. 64 ff.

- ^ mdr.de. "Hilde Benjamin – die "rote Hilde" | MDR.DE". mdr.de (in German). Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ Rudi Beckert: Die erste und die letzte Instanz. Schau- und Geheimprozesse vor dem Obersten Gericht der DDR, Keip Verlag, Goldbach 1995, ISBN 3-8051-0243-7, S. 42

- ^ Andrea Feth (16 January 2002). "Hilde Benjamin (1902–1989)" (PDF). Neue Justiz: Zeitschrift für Rechtsentwicklung und Rechtsprechung in den Neuen Ländern. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG, Baden-Baden. p. 64. ISSN 0028-3231. Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- ^ Volker Müller (5 February 2002). "Warum so milde, Genossen? Vor 100 Jahren wurde Hilde Benjamin geboren, die "rote Hilde" der DDR-Justiz". Berliner Zeitung (online). Archived from the original on 2 February 2016. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ^ John O. Koehler (1999), Stasi: The Untold Story of the East German Secret Police, page 60.

External links

Media related to Hilde Benjamin at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hilde Benjamin at Wikimedia Commons- FemBiographie: Hilde Benjamin (in German)

- Biographie: Hilde Benjamin (in German)

- Biography at ddr-im-www.de (in German)