High Gothic

Reims Cathedral (1211-1299) | |

| Years active | approx. 1200 to 1280 |

|---|---|

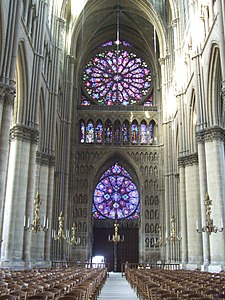

High Gothic was a period of Gothic architecture in the 13th century, from about 1200 to 1280, which saw the construction of a series of refined and richly-decorated cathedrals of exceptional height and size. It appeared most prominently in France, largely thanks to support given by King Louis IX(1226-1270).[1] The goal of High Gothic architects was to bring the maximum possible light from the stained glass windows, and to awe the church goers with lavish decoration.[1] High Gothic is often described as the high point of the Gothic style.[2][3]

High Gothic was a period, rather than a specific style; during the High Gothic period, the Rayonnant style was predominant. Notable High Gothic cathedrals in the Rayonnant style included Reims Cathedral, Amiens Cathedral, Bourges Cathedral, Chartres Cathedral, and Beauvais Cathedral.[4]

The Innovations during the High Gothic period included the reduction of the levels of the nave interior from four to three by merging the Gothic triforium and clerestory. This allowed much larger stained glass windows, which filled the cathedrals with light.[1] The added interior light called for more ornate interior decoration, which was provided by adding designs in stone tracery on the walls.

The period also saw the use of realistic sculpture to decorate both the interior and the exterior, particularly over the church portals. This was influenced by ancient Roman sculpture, which had recently been discovered in Italy.[5]

British and American historians divide the Gothic era into three periods: Early Gothic architecture; High Gothic, including the Rayonnant style, and Late Gothic, including the Flamboyant style. French historians divide the era into four similar phases, Primary Gothic, Gothique Classique or Classic Gothic, Rayonnant Gothic and late Gothic, or Flamboyant.

History

Early examples of Rayonnant High Gothic appeared in Reims Cathedral, where early bar tracery was added between 1215 and 1220. High Gothic elements also appeared in Amiens Cathedral in the choir and clerestory, which were rebuilt after 1236, and at the Basilica of Saint-Denis, when the transepts and nave were rebuilt after 1231.[6] The transept of Chartres Cathedral, was rebuilt after a fire in the new style until 1225.[2]

The royal patronage of cathedrals and other Gothic architecture was expanded by Louis VIII of France and especially Louis IX of France, or Saint Louis; who sponsored the Rayonnant transept rose windows of Notre Dame Cathedral in the 1250s and built Sainte-Chapelle as his royal chapel, consecrated in 1248.[7][2] The High Gothic was exported to other parts of Europe. The most notable example of German High Gothic, or Hochgotik, is Cologne Cathedral, begun in 1248.

French High Gothic

- Reims Cathedral, begun 1211, from the northeast]

- Main portal and side portal, with rose windows

- Buttresses of Reims Cathedral with pinnacles for additional weight

Reims Cathedral was the traditional site of the coronation of the Capetian dynasty and for that reason was given special grandeur and importance.[2] A fire in 1210 destroyed much of the old cathedral, giving an opportunity to build a more ambitious structure, the work began in 1211, but was interrupted by a local rebellion in 1233, and not resumed until 1236. The choir was finished by 1241, but work on the facade did not begin until 1252, and was not finished until the 15th century, with the completion of the bell towers.[8]

Unlike the cathedrals of Early Gothic, Reims was built with just three levels instead of four, giving greater space for windows at the top. it also used the more advanced four-part rib vault, which allowed greater height and more harmony in the nave and choir. Instead of alternating columns and piers, the vaults were supported by rounded piers, each of which was surrounded by a cluster of four attached columns that received the weight of the vaults. In addition to the large rose window on the west, smaller rose windows were added to the transepts and over the portals on the west facade, taking the place of the traditional tympanum. Another new decorative feature, blind arcade tracery, was attached to both interior walls and the facade. Even the flying buttresses were given elaborate decoration; they were crowned by small tabernacles containing statues of saints, which were topped with pinnacles. More than 2300 statues covered both the front and the back side of the facade.[8]

Amiens Cathedral (1220–1266)

- Nave (before 1235) with dark triforia

- Rayonnant choir (after 1236) with lit triforium

- Chevet/apse

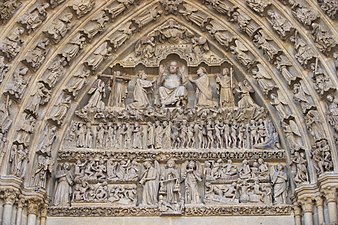

- "Last Judgement" sculpture in the Tympanum of the West front

Amiens Cathedral was begun in 1220 with the ambition of the builders to construct the largest cathedral in France, and they succeeded. It is 145 m (476 ft) long, 70 m (230 ft) wide at the transept, and has a surface area of 7,700 m2 (83,000 sq ft).[9] The nave was finished by 1240 and the choir built between 1241 and 1269.[9] Unusually, the names of the architects are known: Robert de Luzarches, and Thomas and Renaud Cormont. Their names and images are found in the labyrinth in the nave.[9]

The immense size of the cathedral required foundations 9 m (30 ft) deep. The nave has three parts and six crossings, while the choir has double collaterals, and ends in a semicircular disambulatory with seven radiating chapels. The three-level elevation of Amiens, like that of Reims, preceded Chartres Cathedral, but was notably different. The great arcades have a height of eighteen meters, equalling the combined heights of the triforium and the high windows above them. The triforium was more complex than Chartres, and had triple bays with trefoil windows, composed of two slender pointed lancet windows topped with a clover-like rose window.[9] The high windows also had a strikingly complex design; in the nave, each was composed of four tall lancet windows, topped by three small roses; while in the transept the upper windows have as many as eight separate lancets.[9]

The vaults have the exceptional height of 42.4 m (139 ft). They are supported by massive piers composed of four columns which give the nave a striking sensation of verticality. The height of the walls, particularly in the chevet, was made possible by the tall flying buttresses, making two leaps to the wall with the support of an elegant system of arches.[9]

On the exterior, the most remarkable High Gothic feature is the quality of the sculpture of the three porches, decorated altogether with fifty-two statues in their original condition. The most celebrated are on the central portal on the west, dedicated to the Last Judgement, and dominated by the statue of Christ giving a blessing which forms the central column of the doorway.[10] During the intense cleaning of the Cathedral in 1992, traces of paint were discovered indicating that all of the sculpture of the exterior was originally painted with vivid colors. This is now sometimes reproduced by projecting colored light onto the cathedral at night.[10]

Beauvais Cathedral (begun 1225)

- From the west

- The apse, from the east

- Choir and transept of Beauvais Cathedral (after 1284)

Beauvais Cathedral in Picardy is in its principle structures an example of Rayonnant Gothic. It was the most ambitious and most unfortunate of High Gothic projects. Its ambition was to become the tallest of all cathedrals. The choir was built with a height of 48.5 meters (159 ft) However, due most likely to an inadequate foundation and support, the choir vaults fell in 1284. The choir was modified and rebuilt, the polygonal apse and Flamboyant transepts were finished, and in 1569 a new central tower was added, 153 meters (502 feet) high, which made Beauvais for a time the tallest structure in the world. However, in 1573 the central tower collapsed. Some parts were modified or reconstructed, but the tower was never rebuilt and the nave was never finished. Today supports are in place to stabilise the transept. Beauvais remains a majestic but unfinished piece of High Gothic architecture.[11]

German High Gothic

Cologne Cathedral (choir 1248–1322, western parts 1880)

- Seen from the east

- Choir with lit triforium

The construction of the Gothic cathedral of Cologne was started in 1248 by the same Archbishop Konrad von Hochstaden, who promoted the election of William of Holland for ruler of the Holy Roman Empire to finish the rule of Hohenstaufen dynasty, this way. The similarity with Amiens Cathedral is limited to the choir. The towers were projected to a tall height, whereas in Amiens the towers are little higher than the roof of the nave. The choir was completed in 1322 and the decoration of the ambulatory in 1360, but in 1528 the construction ceased until 1823, and the western parts of the Cathedral were completed as late as in 1880.

Utrecht Cathedral (1295)

- Apse and chapels, outside

- Choir, inside

The bishopric of Utrecht was a suffragan of Cologne. In 1456, bishop Henry I van Vianden, who had been a capitular (provost of the chapter) of Cologne Cathedral, laid the first stone for Utrecht Cathedral. Its ambulatory was finished in 1295. The Gothic replacement of the old Romanesque nave began as late as in 1467, and the Late Gothic nave was destroyed by a storm, in 1674.

Characteristics

Plans

The plans of the High Gothic Cathedrals were very similar. They were extremely long and wide, with a minimal transept and maximum interior space. This made possible much larger ceremonies and the ability to welcome larger numbers of pilgrims. One curiosity of the plan of Chartres Cathedral was the floor, which slightly sloped. This was done to facilitate the cleaning of the cathedral after the departure of pilgrims who slept inside the church.[12]

- Reims Cathedral, begun in 1211

- Amiens Cathedral, 1220 – c. 1266

- Beauvais Cathedral, 1190s–1255, the nave, in this plan the lower portion, was never constructed

Elevations

Thanks largely to the efficiency of the flying buttress and six-part rib vaults, all of the major High Gothic cathedrals except Bourges used the three-level elevation, eliminating the tribunes and keeping the ground floor grand gallery, the triforium, and the clerestory, or high windows. The upper windows in particular grew in size to cover almost all of the upper walls. The arcades also grew in height, occupying half the wall, so the triforium was just a narrow band.[13] The upper windows were often made of translucent grisaille glass, which allowed more light than colored stained glass.[14]

- The elevation of Chartres, with the gallery at the bottom, Triforium in the middle, and clerestory at the top

- Vaults triforia and upper windows of Amiens Cathedral[14]

- Three-part elevation of nave of Reims Cathedral

Vaults, piers and pillars

All of the High Gothic Cathedrals except Bourges Cathedral used the newer four-part rib vault, which allowed more even weight distribution to the piers and columns in the nave. Early Gothic churches used alternating piers and columns to support the varying weight from the six-part vaults,

Early Gothic churches used alternating piers and columns to support the varying weight from the six-part vaults, A new variation of rib vault appeared during the High Gothic period; the four-part rib vault, which was used in Chartres Cathedral, Amiens Cathedral and Reims Cathedral.[15] The ribs of this vault distributed the weight more equally to the four supporting piers below, and established a closer connection between the nave and the lower portions of the church walls, and between the arcades below and the windows above.[15] This allowed for greater height and thinner walls, and contributed to the strong impression of verticality given by the newer Cathedrals.[15]

The 11th century Durham Cathedral (1093–1135), with the earlier six-part rib vaults, is 73 feet (22 meters) high. The 12th-century nave of Notre-Dame de Paris, also with six-part rib vaults, is 115 feet, or 35 meters high.[16] The later Amiens Cathedral (built 1220–1266), with the new four-part rib vaults, has a nave that is 138.8 feet (42.3 meters) high.[16]

- Four-part rib vaults at Amiens Cathedral (1220–1270) allowed greater height and larger windows

- Stronger four-part rib vaults at Rouen Cathedral (13th c.)

- The choir of Beauvais Cathedral (1225–1272), the tallest of Gothic church interiors.

- Nave of Cologne Cathedral (1248–1322)

- Hall of the guards of the Conciergerie, part of the earlier royal palace, in Paris (13th century)

In 1192 Notre Dame, which had six-part vaults, had introduced a new kind of support; a central pillar surrounded by four engaged shafts. The pillars supported the gallery, while the shafts continued upwards as colonettes attached to the walls and supported the vaults. Variations of this kind of support gave greater harmony to the appearance of the nave. They frequently had capitals which were decorated with floral sculpture. They appeared at Chartres and then were found, in various forms, in all of the High Gothic Cathedrals.[13]

- The massive pillars, surrounded by colonettes, and topped with floral capitals, of Reims Cathedral

- Transept vaults and pillars of Amiens Cathedral

Flying buttress

The flying buttress was an essential feature of High Gothic architecture; the great height and large upper windows would have been impossible without them. Buttresses with arches apart from the walls had existed in earlier periods, but they were generally small, close to the walls, and were often hidden by the outer architecture. In High Gothic, the buttresses were nearly as tall as the building itself. massive, and meant to be seen; they were decorated with pinnacles and sculpture.

Flying buttresses had been used to support the upper windows of the apse in the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, completed in 1063[17] and then at Notre-Dame de Paris. They were then used in a more ambitious way to support the upper walls of Chartres Cathedral. The first flying buttresses of Chartres were built atop the wall abutments of the nave and choir of the earlier cathedral. They had a double arch reinforced with small columns like the spokes of a wheel. Each small column, with its base and capital, was carved from a single block of stone, Each arch had a sort of stone pyramid on top to add extra weight. Later a second set of arches was added to the nave and choir above the spoked arches, which reached longer and added greater strength.[18]

Similar buttresses were added to each of the High Gothic Cathedrals. The buttresses of each cathedral were unique, and had its own distinct form and decoration. The buttresses of Beauvais Cathedral, the last and tallest High Gothic cathedral, are so high and numerous that they practically hide the cathedral.

- Double arches of the apse of Reims Cathedral, capped with stone pinnacles for greater weight

- Flying buttresses of Amiens Cathedral

- Buttresses practically conceal the choir of Beauvais Cathedral

Stained glass and The Rose Window

A type of small round window, called an oculus, had been used in Romanesque churches.[19] The facade of the Basilica of Saint Denis featured an early rose window on its west front. This was made with plate tracery, where the design was formed by a group of variously shaped openings that appeared to be cut out of the wall. A more ambitious model, with the armature of a wheel made of stone mullions, appeared at Senlis Cathedral in 1200. A similar early Gothic window was constructed for the facade of Chartres Cathedral in 1215. It was soon followed by the High Gothic window of the facade of Laon Cathedral (1200-1215).[20] In 1215, the two great transept windows of Chartres Chathedral were completed. These became the model for many similar windows in France and beyond. The amount of stained glass in Chartres was unprecedented – 164 bays, with 2,600 m2 (28,000 sq ft) of stained glass. A remarkably large amount of the original glass is still in place.[21]

Not long after the introduction of the High Gothic rose window, Gothic architects, fearing that the interiors of the cathedrals were too dark, began experimenting with grisaille windows, which emphasized the important figures in the windows, and also brightened the interiors. These were used at Poitiers Cathedral in 1270 and then by Chartres Cathedral around 1300. Large bands of translucent gray glass were put around the fully colored figures of Christ, The Virgin Mary, and other prominent subjects.[14]

- Glass in the choir of Amiens Cathedral

- West rose window of Reims Cathedral (1252–1275)

- Windows of Beauvais Cathedral

- North transept rose windows, Chartres Cathedral(1250-1260)

Tracery is the term for the intricate designs of slender stone bars and ribs which were used to support the glass and to decorate rose windows and other windows and openings. It also was used increasingly on exterior and interior walls, in the form of stone ribs or molding, to create increasingly intricate forms such as blind arcades. This form was called blind tracery.[22]

The west window of Chartres Cathedral used an early form called plate tracery, a geometric pattern of openings in the stonework filled with glass. Prior to 1230, the builders of Reims Cathedral used a more sophisticated form, called bar tracery, in the apse chapel. This was a pattern of cusped circles, made with thin pointed bars of stone projecting inward.[22] This model was followed and developed in the transept windows of Chartres Cathedral, at Amiens Cathedral and the other High Gothic cathedrals. After the middle of the 13th century, the windows began to be decorated with even larger and complex designs, resembling light shining outwards, which gave the name to the Rayonnant style.[22]

Sculpture

Sculpture was an integral part of High Gothic. It decorated the facades, the walls, the columns, and other architecure, inside and out. It was not considered deocorative; it was designed to serve as a visual Bible for the many parishioners who could not read.

It is probable that some of the sculptors who made the sculpture of the transepts of Chartres travelled north to Reims, where work began in 1210, and possibly also to Amiens Cathedral, where work began in 1218. Nonetheless, the sculpture of each church has its own distinct characteristics. The sculpture of Amiens shows the influence of ancient Roman sculpture, particularly in the realistically modelled drapery of their clothing. The expressions are passive, and the gestures minimal, giving a sense of calm and serenity. The sculpture of Reims showed a similar calm.[23]

The entirely different and more naturalistic High Gothic style of sculpture appeared on the west front Reims Cathedral in the 1240s. This was the work of the sculptor known as Joseph of Reims, named for the vivid smiling statue of Saint Joseph he made for the facade. He also created the Smiling Angel. This famous work was knocked off the Cathedral by a bombardment in World War I, but was carefully reassembled and is now back in its original place.[24] Reims is also noted for the Gallery of Kings, a sculptural depiction of the French Kings crowned at Reims, which begins on the facade and continues on the inside of the facade.

The vegetal decoration of the capitals of the columns of the nave were another distinctive feature of High Gothic sculpture. They were made in finely crafted vegetal forms, complete with birds and other creatures. This followed an ancient Roman model and had been used at Saint-Denis, but at Reims they became much more realistic and detailed. As the work continued toward the west in the nave, the foliage became more abundant and filled with life. This model was copied in Gothic cathedrals first in France, and then across Europe.[25]

- "The Smiling Angel" (1236–45) from Reims Cathedral

- Sculpture in the Gallery of Kings of Reims Cathedral

- Central tympanum on facade of Amiens Cathedral

- Accurately sculpted vegetation (horse chestnuts) on the column capitals of Reims Cathedral

References

- ^ a b c "High Gothic", Encyclopaedia Britannica on-line (by subscription) retrieved February 2024

- ^ a b c d Watkin 1986, p. 132.

- ^ "Églises de l'Oise by Dominique Vermand, subpage for Beauvais Cathedral". Archived from the original on 2023-05-01. Retrieved 2023-05-02.

- ^ "The High Gothic years (c. 1250–1300), heralded by Chartres Cathedral, were dominated by France, especially with the development of the Rayonnant style." Encyclopedia Britannica on-line (by subscription), "High Gothic"

- ^ "High Gothic sculpture", Encyclopaedia Britannica on-line, retrieved February 2024 (by subscription)

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica on-line, (by subscription), "High Gothic"

- ^ Branner, Robert (1965). St. Louis and the Court style in Gothic architecture. London: A. Zwemmer. ISBN 0-302-02753-X.

- ^ a b Mignon 2015, p. 26.

- ^ a b c d e f Mignon 2015, p. 28.

- ^ a b Mignon 2015, p. 29.

- ^ Watkin 1986, p. 135.

- ^ Houvet 2019, p. 23.

- ^ a b Ducher 2014, p. 42.

- ^ a b c Chastel 2000, p. 146.

- ^ a b c Renault & Lazé 2006, p. 34.

- ^ a b Watkin 1986, p. 134.

- ^ Mignon 2015, p. 19.

- ^ Houvet 2019, p. 20.

- ^ O'Reilly 1921, Chapter one, Loc. 2607 (Project Gutenberg text).

- ^ Chastel 2000, p. 144–146.

- ^ Chastel 2000, p. 129.

- ^ a b c "Tracery". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- ^ Martindale 1993, p. 48.

- ^ Martindale 1993, p. 50–51.

- ^ Martindale 1993, p. 51.

Bibliography

In English

- Bony, Jean (1985). French Gothic Architecture of the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-05586-1.

- Houvet, E (2019). Miller, Malcolm B (ed.). Chartres - Guide of the Cathedral. Éditions Houvet. ISBN 2-909575-65-9.

- Martindale, Andrew (1993). Gothic Art. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-2-87811-058-6.

- Watkin, David (1986). A History of Western Architecture. Barrie and Jenkins. ISBN 0-7126-1279-3.

- O'Reilly, Elizabeth Boyle (1921). How France Built Her Cathedrals - A study in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries. Harper and Brothers.

In French

- Chastel, André (2000). L'Art Français Pré-Moyen Âge Moyen Âge (in French). Flammarion. ISBN 2-08-012298-3.

- Ducher, Robert (2014). Caractéristique des Styles (in French). Flammarion. ISBN 978-2-0813-4383-2.

- Mignon, Olivier (2015). Architecture des Cathédrales Gothiques (in French). Éditions Ouest-France. ISBN 978-2-7373-6535-5.

- Renault, Christophe; Lazé, Christophe (2006). Les Styles de l'architecture et du mobilier (in French). Gisserot. ISBN 9-782877-474658.

- Wenzler, Claude (2018), Cathédales Gothiques - un Défi Médiéval, Éditions Ouest-France, Rennes (in French) ISBN 978-2-7373-7712-9

- Le Guide du Patrimoine en France (2002), Éditions du Patrimoine, Centre des Monuments Nationaux (in French) ISBN 978-2-85822-760-0

![Reims Cathedral, begun 1211, from the northeast]](Https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/11/ReimsCathedral0116.jpg/355px-ReimsCathedral0116.jpg)