Heinrich Barth

Heinrich Barth | |

|---|---|

Heinrich Barth | |

| Born | 16 February 1821 |

| Died | 25 November 1865 (aged 44) |

| Nationality | German |

| Occupation(s) | African explorer and scholar |

| Awards | Patron's Medal of the Royal Geographical Society (1856) Companionship of the Bath (1862) |

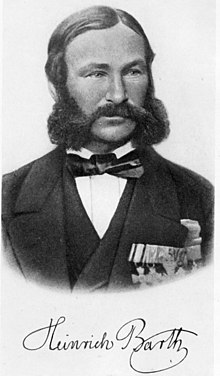

Johann Heinrich Barth (/bɑːrθ, bɑːrt/;[1][2] German: [baʁt]; 16 February 1821 – 25 November 1865) was a German explorer of Africa and scholar.

Barth is thought to be one of the greatest of the European explorers of Africa, as his scholarly preparation, ability to speak and write Arabic, learning African languages, and character meant that he carefully documented the details of the cultures he visited. He was among the first to comprehend the uses of oral history of peoples, and collected many. He established friendships with African rulers and scholars during his five years of travel (1850–1855). After the deaths of two European companions, he completed his travels with the aid of Africans. Afterwards, he wrote and published a five-volume account of his travels in both English and German. It has been invaluable for scholars of his time and since.

Early life and education

Heinrich Barth was born in Hamburg on 16 February 1821. He was the third child of Johann Christoph Heinrich Barth and his wife Charlotte Karoline née Zadow. Johann had come from a relatively poor background but had built up a successful trading business. Both parents were orthodox Lutherans and they expected their children to conform to their strict ideas on morality and self-discipline.[3] From the age of eleven Barth attended the prestigious high school, the Gelehrtenschule des Johanneums, in Hamburg.[4] He was very studious but not popular with his classmates. He excelled at languages and taught himself some Arabic.[5] Barth left school aged 18 in 1839 and immediately enrolled at the University of Berlin where he attended courses offered by the geographer Karl Ritter, the classical scholar August Böckh and the historian Jakob Grimm. After his first year, he interrupted his studies and went on a tour of Italy visiting Venice, Florence, Rome, Naples and Sicily, returning to Germany in the middle of May 1841.[6] In the vacation of the following year, he visited the Rhineland and Switzerland.[7] He defended his doctoral thesis on the trade relations of ancient Corinth in July 1844.[8][9]

Visit to North Africa and the Near East

Barth formed a plan to undertake a grand tour of north Africa and the Middle East which his father agreed to fund. He left his parents' home at the end of January 1845 and first visited London where he spent two months learning Arabic, visiting the British Museum and securing the protection of the British consuls for his trip. While in London, he met the Prussian ambassador to Britain, Christian von Bunsen, who would later play an important role in his trip to central Africa. He left London and travelled across France and Spain. On 7 August he caught a ferry from Gibraltar to Tangiers for his first visit to Africa.[10][11][12] From Tangier, he made his way overland across North Africa. He also travelled through Egypt, ascending the Nile to Wadi Halfa and crossing the desert to the port of Berenice on the Red Sea. While in Egypt, he was attacked and wounded by robbers. Crossing the Sinai peninsula, he traversed Palestine, Syria, Asia Minor, Turkey and Greece, everywhere examining the remains of antiquity.[13] He returned to his parents' home in Hamburg on 27 December 1847 after a trip of almost three years.[14] For a time he was engaged there as Privatdozent. He described some of his travels in the first volume of his book, Wanderungen durch die Küstenländer des Mittelmeeres, (Walks through the coastal states of the Mediterranean) which was published in 1849.[15] The intended second volume never appeared.[16]

Expedition to the Sudan, the Sahara and Western Africa

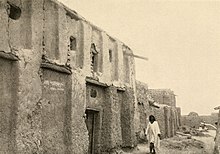

Christian Bunsen, the Prussian ambassador to Westminster, encouraged the appointment of scholars, including Barth and Adolf Overweg, a Prussian astronomer, to the expedition of James Richardson, an explorer of the Sahara.[17] Richardson had been selected by the British government to open up commercial relations with the states of the central and western Sudan.[13] The party left Marseilles in late 1849, and departed from Tripoli early in 1850. They crossed the Sahara Desert with great difficulty. He arrived in the city of Agadez in October 1850 where he stayed for several days. Today a memorial tablet honours him as the first European to have ever entered the city.

The deaths of Richardson (March 1851) and Overweg (September 1852), who died of unknown diseases, left Barth to carry on the scientific mission alone. Barth was the first European to visit Adamawa in 1851. When he returned to Tripoli in September 1855, his journey had extended over 24° of latitude and 20° of longitude, from Tripoli in the north to Adamawa and Cameroon in the south, and from Lake Chad and Bagirmi in the east to Timbuktu (September 1853) in the west – upward of 12,000 miles (19,000 km). He studied minutely the topography, history, civilizations, languages, and resources of the countries he visited.[13] His success as an explorer and historian of Africa was based both on his patient character and his scholarly education.

Barth was interested in the history and culture of the African peoples, rather than the possibilities of commercial exploitation. Due to his level of documentation, his journal has become an invaluable source for the study of 19th-century Sudanic Africa. Although Barth was not the first European visitor who paid attention to the local oral traditions, he was the first who seriously considered its methodology and use for historical research. Barth was the first true European scholar to travel and study in West Africa. Earlier explorers such as René Caillié, Dixon Denham and Hugh Clapperton had no academic knowledge.

Barth was fluent in Arabic and several African languages (Fulani, Hausa and Kanuri) and was able to investigate the history of some regions, particularly the Songhay Empire. He established close relations with a number of African scholars and rulers, from Umar I ibn Muhammad al-Amin in Bornu, through the Katsina and Sokoto regions to Timbuktu. There his friendship with Ahmad al-Bakkai al-Kunti led to his staying in his house; he also received protection from al-Kunti against an attempt to seize him.

After his return to London Barth wrote and published accounts of his travels simultaneously in English and German, under the title Reisen und Entdeckungen in Nord- und Centralafrika (Travels and Discoveries in North and Central Africa; 1857–1858, 5 volumes., approx. 3,500 pages). The volumes included coloured plates of pictures produced by Martin Bernatz based on Barth's original sketches.[18] The work was considered one of the finest of its kind, being cited by Darwin.[19] It is still used by historians of Africa, and remains an important scientific work on African cultures of the age. It also provided the first evidence by a European that the Sahara had once been a savanna.[20][21]

Later life

Barth returned from Great Britain to Germany, where he prepared a collection of Central African vocabularies (Gotha, 1862–1866).[22] In 1858 he undertook another journey in Asia Minor, and in 1862 visited the Turkish provinces in Europe.[13] He wrote an account of these travels that was published in Berlin in 1864.[23]

In the following year he was granted a professorship of geography (without chair or regular pay) at Berlin University and appointed president of the Geographical Society.[13] His admission to the Prussian Academy of Sciences was denied, as it was claimed that he had achieved nothing for historiography and linguistics. They did not fully understand his achievements, which have been ratified by scholars over time.

Barth died in Berlin on 25 November 1865 aged 44.[a] His grave is preserved in the Protestant Friedhof III der Jerusalems- und Neuen Kirchengemeinde (Cemetery No. III of the congregations of Jerusalem's Church and New Church) in Berlin-Kreuzberg, south of Hallesches Tor.

Legacy and honours

- 1856 Patron's Medal of the Royal Geographical Society for his African journeys[28]

- 1862 Companionship of the Bath from the British government[29]

Barth is commemorated in the scientific name of a species of African venomous snake, Polemon barthii.[30]

Selected publications

For a full list see Wilhelm Koner (1866).[31]

- Barth, Henricus (1844). Corinthiorum commercii et mercaturae historiae particula (Doctoral Dissertation) (in Latin). Berlin: Typis Unger.

- Barth, Heinrich (1849). Wanderungen durch die Küstenländer des Mittelmeeres: ausgeführt in den Jahren 1845, 1846 und 1847, Volume 1 [Walks through the coastal states of the Mediterranean: executed in the years 1845, 1846 and 1847] (in German). Berlin: Hertz. Only the first volume was published.

- Barth, Heinrich (1857–1858). Reisen und Entdeckungen in Nord- und Central-afrika in den Jahren 1849 bis 1855 (5 volumes) (in German). Gotha: J. Perthes. Volume 1, Volume 2, Volume 3, Volume 4, Volume 5

- Barth, Henry (1857–1858). Travels and Discoveries in North and Central Africa: being a Journal of an Expedition undertaken under the Auspices of H.B.M.'s Government, in the Years 1849–1855 ... 5 volumes. London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans and Roberts.. Google Books: Volume 1 (1857), Volume 2 (1857), Volume 3 (1857), Volume 4 (1858), Volume 5 (1858). US-edition with fewer pictures. 3 volumes. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1857. Google Books: Volume 1 (1857), Volume 2 (1857),Volume 3 (1859), Project Gutenberg: Volume 1 (1857).

- Barth, H. (1860). Dr. H. Barth's reise von Trapezunt durch die nördliche hälfte Klein-Asiens nach Scutari im herbst 1858. Gotha: J. Perthes.

- Barth, H. (1860). "A general historical description of the state of human society in Northern Central Africa". Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London. 30: 112–128. doi:10.2307/1798293. JSTOR 1798293.

- Barth, Heinrich (1862–1866). Sammlung und bearbeitung central-afrikanischer vokabularien; Collection of vocabularies of Central-African languages (3 Volumes) (in German and English). Gotha: Justas Perthes. Volume 1, Volume 2, Volume 3.

- Barth, Heinrich (1864). Reise durch das Innere der Europäischen Türkei von Rustchuk über Philippopel, Rilo (Monastir), Bitolia und den Thessalischen Olym nach Saloniki (in German). Berlin: Dietrich Reimer.

Notes

References

- ^ Kirk-Greene 1962, p. 1.

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, p. 665, ISBN 9781405881180

- ^ Schubert 1897, pp. 1-2.

- ^ Schubert 1897, pp. 4-5.

- ^ Schubert 1897, pp. 6-7.

- ^ Schubert 1897, pp. 8-9.

- ^ Schubert 1897, p. 16.

- ^ Barth 1844.

- ^ Kirk-Greene 1962, p. 3.

- ^ Schubert 1897, pp. 19-21.

- ^ Barth 1849, p. vii.

- ^ Kirk-Greene 1962, pp. 3–4.

- ^ a b c d e Chisholm 1911.

- ^ Schubert 1897, p. 23.

- ^ Barth 1849.

- ^ Kirk-Greene 1962, p. 5.

- ^ Prothero, R. Mansell (1958). "Heinrich Barth and the Western Sudan". The Geographical Journal. 124 (3): 326–337. doi:10.2307/1790783. ISSN 0016-7398. JSTOR 1790783.

- ^ Barth 1857–1858, p. xxiii Vol 1.

- ^ Darwin 1868, p. 308.

- ^ Barth 1857, vol. 1, chapter IX, pp. 196–199. On p. 199, Barth said, about a petroglyph depicting ancient hunters in the Sahara, that it " … bears testimony to a state of life very different from that which we are accustomed to see now in these regions, … "

- ^ de Menocal, Peter B. ; Tierney, Jessica E. (2012) "Green Sahara: African humid periods paced by Earth's orbital changes", Nature Education Knowledge 3(10): 12. Available at: Nature Education: Knowledge Project

- ^ Barth 1862–1866.

- ^ Barth 1864.

- ^ Kirk-Greene 1962, p. 42.

- ^ Koner 1866, p. 28.

- ^ Schubert 1897, p. 173.

- ^ Kemper 2012, pp. 364, 390.

- ^ "Medals and Awards: Gold Medal Recipients". Royal Geographical Society. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- ^ Schubert 1897, p. 138.

- ^ Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. ("Barth", p. 18).

- ^ Koner 1866, pp. 28-31.

Sources

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Barth, Heinrich". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 447.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- Darwin, Charles (1868). The variation of animals and plants under domestication, Volume 1. London: John Murray.

- Kemper, Steve (2012). A Labyrinth of Kingdoms: 10,000 Miles through Islamic Africa. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-07966-1.

- Kirk-Greene, A.H.M., ed. (1962). Barth's Travels in Nigeria: Extracts from the Journal of Heinrich Barth's Travels in Nigeria, 1850-1855. London: Oxford University Press. OCLC 6083393.

- Koner, W. (1866). "Heinrich Barth: Vortrag gehalten in der Sitzung der geographischen Geselaschaft am 19 Januar 1866". Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Erdkunde zu Berlin (in German). 1: 1–31.

- Schubert, Gustav von (1897). Heinrich Barth, der Bahnbrecher des deutschen Afrikaforschung; ein Lebens- und Charakterbild auf Grund ungedruckter Quellen entworfen (in German). Berlin: D. Reimer.

Further reading

- Boahen, Albert Adu (1964). Britain, the Sahara and the Western Sudan, 1788-1861. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-821625-4.

- de Moraes Farias, Paulo Fernando; Diawara, Mamadou; Spittler, Gerd, eds. (2006). Heinrich Barth et l'Afrique (in French and English). Köppe. ISBN 978-3-89645-220-7.

- Fischer–Kattner, Anke (2018). "Explorateur, ethnographe, antihéros : vie et œuvre de Heinrich Barth", in BEROSE - International Encyclopaedia of the Histories of Anthropology, Paris.

- Kuba, Richard (2019). "Heinrich Barth, une vie de chercheur", in BEROSE - International Encyclopaedia of the Histories of Anthropology, Paris.

- Masonen, Pekka (2000). The Negroland Revisited: Discovery and Invention of the Sudanese Middle Ages. Helsinki: Finnish Academy of Science and Letters. pp. 397–418. ISBN 951-41-0886-8.

- Murchison, Roderick I. (1866). "Obituary: Dr. Barth". Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society of London. 10: 201–203.

- Petermann, Augustus, ed. (1854). An account of the progress of the expedition to Central Africa in the years 1850, 1851, 1852, and 1853, under Richardson, Barth, Overweg and Vogel, consisting of maps and illustrations with descriptive notes (PDF). London: Stanford. OCLC 257397111.

- Richardson, James (1853). Narrative of a mission to Central Africa : performed in the years 1850-51 : under the orders and at the expense of Her Majesty's government (2 volumes). London: Chapman and Hall.

- Schiffers, Heinrich (1967). "Heinrich Barth Lebensweg". In Schiffers, H. (ed.). Heinrich Barth. Ein Forscher in Afrika. Leben - Werk - Leistung. Eine Sammlung von Beiträgen zum 100. Todestag am 25 November 1965 (in German). Wiesbaden: Steiner. pp. 1–57. OCLC 5182712.

- Fischer‑Kattner, Anke, 2018. "Explorateur, ethnographe, antihéros : vie et œuvre de Heinrich Barth" in Bérose - Encyclopédie internationale des histoires de l’anthropologie

External links

- Works by Heinrich Barth at the Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Works by Heinrich Barth at Open Library

- Heinrich-Barth-Institut for Archaeology and Environmental History of Africa (Heinrich-Barth-Institut e.V. für Archäologie und Umweltgeschichte Afrikas), University of Cologne

- Scan of one of Barth's notebooks, Gallica. Contains vocabulary and fragments of his journal between 18 November 1853 and 31 July 1854.

- Newspaper clippings about Heinrich Barth in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- Works by or about Heinrich Barth at the Internet Archive