HMS Juno (1780)

Juno | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | HMS Juno |

| Ordered | 21 October 1778 |

| Builder | Robert Batson & Co, Limehouse |

| Laid down | December 1778 |

| Launched | 30 September 1780 |

| Completed | 14 December 1780 |

| Honours and awards | Naval General Service Medal with clasp "Schiermonnikoog 12 Augt. 1799" |

| Fate | Broken up in July 1811 |

| General characteristics [1] | |

| Class and type | 32-gun Amazon-class fifth-rate frigate |

| Tons burthen | 68929⁄94 (bm) |

| Length |

|

| Beam | 35 ft 2+1⁄4 in (10.7 m) |

| Draught | 8 ft (2.4 m) |

| Depth of hold | 12 ft 1+1⁄2 in (3.7 m) |

| Sail plan | Full-rigged ship |

| Complement | 220 |

| Armament |

|

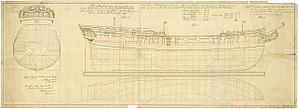

HMS Juno was a Royal Navy 32-gun Amazon-class fifth rate. This frigate served during the American War of Independence, and the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars.

Construction and commissioning

Juno was ordered on 21 October 1778 and laid down in December that year at the yards of the shipbuilder Robert Batson & Co, of Limehouse.[1] She was launched on 30 September 1780 and completed by 14 December 1780 that year at Deptford Dockyard.[2] £8,500 1s 5d was paid to the builder, with a further £8,184 18s 1d being spent on fitting her out and having her coppered.[1]

Early years

Juno was commissioned under the command of her first captain, James Montagu, in September 1780.[1] Montagu commanded her for the next five years, initially in British waters and the Atlantic.

On 10 February 1781 Juno and the sloop Zebra captured the American privateer Revanche (or Revenge) off Beachy Head.[3] Montagu then sailed the Juno in early 1782 to join Richard Bickerton's squadron operating in the East Indies.[1]

She was present at the Battle of Cuddalore on 20 June 1783, and returned to Britain to be paid off in March 1785. After fitting out the following month Juno was placed in ordinary.[1] She spent the next five years in this state, with the exception of a small repair at Woolwich Dockyard in 1788 at a cost of £9,042.[1]

French Revolutionary Wars

Juno returned to active service in May 1790, now under the command of Captain Samuel Hood.[1] Hood sailed to Jamaica in mid-1790, but had returned to Britain and paid off the Juno in September 1791. Hood however remained in command, and the Juno was fitted out and recommissioned, undergoing a refit at Portsmouth in January 1793.[1] Hood initially cruised in the English Channel after the outbreak of the French Revolutionary Wars, capturing the privateers Entreprenant on 17 February, Palme on 2 March and, together with HMS Aimable, Laborieux in April.[1]

Hood was then transferred to the Mediterranean in May 1793.

Juno was at Toulon during its period of British control under Samuel Hood, Juno's captain's cousin once removed. Unaware that Toulon had fallen to French republican forces, and desiring to deliver 107 Maltese and 46 Marines embarked in Malta to reinforce Lord Hood's forces, Captain Hood sailed into the port at night on 11 January 1794, several days after the evacuation of the British forces.[4][5] After anchoring, Juno was boarded by 13 armed men.[6][7] On being informed that British forces had left and that he and his ship's company were now prisoners of war, Captain Hood ordered cables to be cut and immediately set sail with the 13 French officials aboard as prisoners, whereupon Juno received a broadside from a nearby brig and came under point-blank fire from French batteries, but was able to escape with only light damage.[5]

On 7 February 1794 Juno and the 74-gun HMS Fortitude carried out an attack on a tower at Mortella Point, on the coast of Corsica.[4] The design of the tower allowed it to hold out against the British for several days, and inspired the design of the subsequent Martello Towers constructed in Great Britain and other British possessions.[8]

Captain Lord Amelius Beauclerk succeeded Hood, who returned to Britain with a convoy in October 1795, and paid her off in January the following year.[4]

Juno was repaired and refitted at Deptford for the sum of £20,442. She was recommissioned in August 1798 under the command of Captain George Dundas.[4] She operated with a British squadron in Anglo-Russian invasion of Holland in August 1799 that resulted in the surrender on 13 August, without firing of a shot, of a Dutch squadron of one small 74, six 64s, two 50s, and six 44s, five frigates, three corvettes, and one brig.

Schiermonnikoog

On 11 August 1799, the 16-gun sloop Pylades, under Captain Adam Mackenzie, the 16-gun brig-sloop Espiegle, under Captain James Boorder, the 12-gun hired cutter Courier, and Juno and Latona, which sent their boats, mounted an attack on Crash, which was moored between the island of Schiermonnikoog and Groningen.[9][10]

Pylades and Espiegle engaged Crash, which surrendered after a strong resistance. MacKenzie immediately put Crash into service under Lieutenant James Slade, Latona's first lieutenant.[10] In the attack, Pylades lost one man killed and three wounded. Juno lost one man killed when the boats attacked a gun-schooner.[10]

The next day the British captured one schyut and burnt a second. MacKenzie put Lieutenant Salusbury Pryce Humphreys of Juno on the captured schuyt after arming her with two 12-pounder carronades and naming her the Undaunted.[10]

On 13 August the British attacked the Dutch schooner Vengeance (or Weerwrack or Waarwrick), of six cannons (two of them 24-pounders), and a battery on Schiermonnikoog.[10] The British were able to burn the Vengeance and spike the battery's four guns.[9] They also captured a rowboat with 30 men and two brass 4-pounder field pieces,[9] and spiked another 12-pounder.[10] The Courier grounded but was saved. Including Undaunted, the British captured three schuyts or galiots, the Vier Vendou, the Jonge Gessina and one other.[11] The battle would earn those seamen who survived until 1847 the Naval General Service Medal with clasp "Schiermonnikoog 12 Augt. 1799".[12]

On 12 February 1800 Juno and Busy sailed for Jamaica as escorts to a convoy of 150 merchant vessels.[13]

On 2 June Juno and Melampus, were in company when they captured Volante.[a] On 1 October Juno, Melampus, and Retribution were in company when they captured the Aquila.[b]

Napoleonic Wars

Captain Isaac Manley took command in 1802, paying off Juno in the middle of the year.[4] A further refit followed, with Juno returning to sea under the command of Captain Henry Richardson. Richardson took Juno to the Mediterranean in April 1803. Between 1 and 3 August 1803, Juno and Morgiana captured three vessels: Santissima Trinita, Parthenope, and Famosa.[15] Then on the 21st, Juno and Morgiana captured San Giorgio.[16]

On 8 September Juno was eight leagues off Cape Sparivento when she captured the French bombarde privateer Quatre Fils, of Nice. Quatre Fils was armed with four guns (12 and 9-pounders), and had a crew of 78 men.[17]

In 1805 Juno and several other frigates and sloops arrived at Gibraltar where Nelson employed them to harass coastal shipping that was resupplying the Franco-Spanish fleet at Cadiz.

In 1806 Juno was then active in the Bay of Naples, supporting Sidney Smith's operations there.[4] When Smith had arrived in Palermo on 21 April 1806 he found that Gaeta still held out against the French even though the Neapolitan government had had to cede the capital. Smith had immediately sent two convoys to Gaeta with supplies and ammunition and landed four 32-poundeer guns from Excellent. Smith also stationed Juno off Gaeta, where she was in a flotilla together with the Neapolitan frigate Minerva, Captain Vieugna, and 12 Neapolitan gun-boats.

Next, the French erected a battery of four guns on the point of La Madona della Catena. The Prince of Hesse-Philipstad put 60 men from the garrison at Gaeta in four fishing-boats and on the night of 12 May Richardson took them and the boats from Juno and Minerva to a small bay in the French rear. As the boats reached shore, the French signaled the attack and abandoned the battery. The landing party spiked the guns and destroyed the carriages unopposed. It then re-embarked, having sustained no losses.[18]

On 15 May the garrison at Gaeta made another modestly successful sortie. Two divisions of gunboats supported the operation. Richardson commanded one division. Juno's boats, under the command of Lieutenant Thomas Wells, assisted by Lieutenant of marines Robert M. Mant joined the attack. Juno's boats sustained the allies' only loss, which consisted of four seamen killed and five wounded.[18]

On 18 July 1806 the French under André Masséna captured Gaeta after an heroic defence. In 1809 it became a duché grand-fief in the Napoleonic Kingdom of Naples, but under the French name "Gaete", for finance minister Martin-Michel-Charles Gaudin.

Fate

Captain Charles Schomberg succeeded Richardson in February 1807. Captain Granville Proby replaced Schomberg in July that year, with orders to sail Juno back to Britain. She was placed in ordinary at Woolwich after her arrival, and was broken up there in July 1811.[2][4]

Notes

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Winfield. British Warships of the Age of Sail. p. 203.

- ^ a b Colledge. Ships of the Royal Navy. p. 181.

- ^ "No. 12205". The London Gazette. 7 July 1781. p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e f g Winfield. British Warships of the Age of Sail. p. 204.

- ^ a b Forczyk & Hook. Toulon, 1793. p. 83.

- ^ George Thorp letter-books.

- ^ Thorp. George Thorp (1790–1797) - A Naval Lieutenant killed at Santa Cruz.

- ^ Sutcliffe. Martello towers. p. 20.

- ^ a b c "No. 15171". The London Gazette. 20 August 1799. p. 837.

- ^ a b c d e f "No. 15172". The London Gazette. 24 August 1799. pp. 849–850.

- ^ "No. 15350". The London Gazette. 31 March 1801. p. 365.

- ^ "No. 20939". The London Gazette. 26 January 1849. p. 239.

- ^ Naval Chronicle, Vol. 3, p. 155.

- ^ a b "No. 18590". The London Gazette. 3 July 1829. p. 1246.

- ^ "No. 16668". The London Gazette. 14 November 1812. p. 2303.

- ^ "No. 16300". The London Gazette. 23 September 1809. p. 1544.

- ^ "No. 15642". The London Gazette. 10 November 1803. p. 1554.

- ^ a b James (1837), Vol. 4, 216.

References

- Colledge, J. J.; Warlow, Ben (2006) [1969]. Ships of the Royal Navy: The Complete Record of all Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy (Rev. ed.). London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-281-8.

- Forczyk, Robert A.; Hook, Adam (2005). Toulon 1793: Napoleon's First Great Victory. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-919-3.

- James, William (1902) The Naval History of Great Britain from the declaration of war by France in 1793 to the accession of George IV. Vol. 4. (London).

- Sutcliffe, Sheila (1973). Martello Towers. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. ISBN 0-8386-1313-6.

- Winfield, Rif (2007). British Warships of the Age of Sail 1714–1792: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Seaforth. ISBN 1-86176-295-X.

- Winfield, Rif (2008). British Warships in the Age of Sail 1793–1817: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-84415-717-4.