Golden Age of India

Certain historical time periods have been named "golden ages", where development flourished, including on the Indian subcontinent.[1][2]

Ancient era

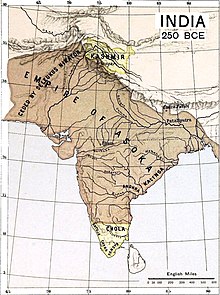

Maurya Empire

The Maurya Empire (321–185 BC) was the largest and one of the most powerful empires to exist in the history of the Indian subcontinent. This era was accompanied by high levels of cultural development and economic prosperity. The empire saw significant advancements in the fields of literature, science, art, and architecture. Important works like the Sushruta Samhita were written and expanded in this period.[4] The earlier development of the Brahmi script and Prakrit languages took place during this period, and these later formed the bases of other languages. This era also saw the emergence of scholars like Acharya Pingal and Patanjali, who made great advancements in the fields of mathematics, poetry, and yoga.[5] The Maurya Empire was notable for its efficient administrative system, which included a large network of officials and bureaucrats as well as a sophisticated system of taxation and a well-organized army.[6][7]

According to estimates given by historians, during the Maurya era, the Indian subcontinent generated close to one third of global GDP, which would be the highest the region would ever contribute.[8]

Classical era

Gupta Empire

The period between the 4th and 6th centuries CE is known as the Golden Age of India because of the considerable achievements that were made in the fields of mathematics, astronomy, science, religion, and philosophy, during the Gupta Empire.[9][10] The decimal numeral system, including the concept of zero, was invented in India during this period.[11] The peace and prosperity created under the leadership of the Guptas enabled the pursuit of scientific and artistic endeavors in India.[12][13][14] The Golden Age of India came to an end when the Hunas invaded the Gupta Empire, in the 6th century CE, although this characterisation has been disputed by some other historians.[note 1][note 2] The gross domestic product (GDP) of ancient India was estimated to be 32% and 28% of global GDP in 1 AD and 1000 AD, respectively.[17] Also, during the first millennium of the Common Era, the Indian population comprised approximately 27.15%–30.3% of the total world population.[18][19][20]

Late Middle Ages and early modern era

Mughal Empire

The Mughal Empire has often been called the last golden age of India.[22][23] It was founded in 1526 by Babur of the Barlas clan, after his victories at the First Battle of Panipat and the Battle of Khanwa, against the Delhi Sultanate and Rajput Confederation, respectively.[24][25] Over the following centuries, under Akbar, Jahangir, and Shah Jahan, the Mughal Empire would grow in area and power and dominate the Indian subcontinent, reaching its maximum extent under Aurangzeb. This imperial structure lasted until 1720, shortly after the death of Aurangzeb,[26][27] following which it gradually converted from a centralised autocracy into a collection of autonomous vassal states who accepted the nominal suzerainty of the emperor. The empire was formally dissolved by the British Raj after the Indian Rebellion of 1857.

The Mughals adopted and standardised the rupee (rupiya, or silver) and dam (copper) currencies introduced by Sur emperor Sher Shah Suri during his brief rule.[28]

A major sector of the Mughal economy was agriculture.[29] A variety of crops were grown, including food crops such as wheat, rice, and barley, and non-food cash crops such as cotton, indigo, and opium. By the mid-17th century, Indian cultivators began to extensively grow maize and tobacco, imported from the Americas.[29] The Mughal administration emphasised agrarian reform, started by Sher Shah Suri, the work of which Akbar adopted and furthered with more reforms. The civil administration was organised in a hierarchical manner on the basis of merit, with promotions based on performance, exemplified by the common use of the seed drill among Indian peasants,[30] and built irrigation systems across the empire, which produced much higher crop yields and increased the net revenue base, leading to increased agricultural production.[29]

Manufacturing was also a significant contributor to the Mughal economy; the empire produced about 25% of the world's industrial output until the end of the 18th century.[31] Manufactured goods and cash crops were sold throughout the world. Key industries included textiles, shipbuilding, and steel. Processed products included cotton textiles, yarns, thread, silk, jute products, metalware, and foods such as sugar, oils, and butter[29] The Mughal Empire also took advantage of the demand for Indian products in Europe, particularly cotton textiles, as well as goods such as spices, peppers, indigo, silks, and saltpeter (for use in munitions).[29] European fashion, for example, became increasingly dependent on Mughal Indian textiles and silks. From the late 17th century to the early 18th century, India accounted for 95% of British imports from Asia, and Bengal Subah province alone accounted for 40% of Dutch imports from Asia.[32]

The largest manufacturing industry in the Mughal Empire was textile manufacturing, particularly cotton, which included the production of piece goods, calicos, and muslins.[33] By the early 18th century, Mughal Indian textiles were clothing people across the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia, Europe, the Americas, Africa, and the Middle East.[34] The most important centre of cotton production was Bengal province, particularly around its capital city of Dhaka.[35]

Notes

- ^ According to D. N. Jha, caste distinctions became more entrenched and rigid during this time, as prosperity and the favour of the law accrued to the top of the social scale, while the lower orders were degraded further.[15]

- ^ "Historians once regarded the Gupta period (c.320–540) as the classical age of India [...] It was also thought to have been an age of material prosperity, particularly among the urban elite [...] Some of these assumptions have been questioned by more extensive studies of the post-Mauryan, pre-Gupta period. Archaeological evidence from the earlier Kushan levels suggests greater material prosperity, to such a degree that some historians argue for an urban decline in the Gupta period."[16]

References

- ^ The Mughal World, p. 386, Abraham Eraly, Penguin Books

- ^ Cultural Sociology of the Middle East, Asia, and Africa p. 29, Andrea L. Stanton, SAGE

- ^ Joppen, Charles. Historical atlas of India, for the use of high schools, colleges and private students. Cornell University Library. London; New York: Longmans, Green. pp. map 2.

- ^ Olivelle 2013, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Plofker, Kim (2009). Mathematics in India. Princeton University Press. pp. 55–56. ISBN 978-0-691-12067-6.

- ^ The Maurya Empire: The History and Legacy of Ancient India's Greatest Empire. Charles River Editors. 2017.

- ^ Cultural Sociology of the Middle East, Asia, and Africa p. 29, Andrea L. Stanton, SAGE

- ^ Angus Maddison (2007). Contours of the World Economy, 1–2030 AD. Essays in Macro-Economic History. Oxford University Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-19-922721-1.

- ^ Building Bridges Among the BRICs, p. 125, Robert Crane, Springer, 2014

- ^ Keay, John (2000). India: A history. Atlantic Monthly Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-87113-800-2.

The great era of all that is deemed classical in Indian literature, art and science was now dawning. It was this of creativity and scholarship, as much as ... political achievements of the Guptas, which would make their age so golden.

- ^ "THE GUPTA EMPIRE OF INDIA 320-720".

- ^ Padma Sudhi. Gupta Art: A Study from Aesthetic and Canonical Norms. Galaxy Publications. p. 7-17.

- ^ Lee Engfer (2002). India in Pictures. Twenty-First Century Books. ISBN 9780822503712.

- ^ "Patanjali", Wikipedia, 13 April 2023, retrieved 14 April 2023

- ^ Jha, D.N. (2002). Ancient India in Historical Outline. Delhi: Manohar Publishers and Distributors. pp. 149–73. ISBN 978-81-7304-285-0.

- ^ Pletcher 2011, p. 90.

- ^ Angus Maddison (2007). Contours of the World Economy, 1–2030 AD. Essays in Macro-Economic History. Oxford University Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-19-922721-1.

- ^ Angus Maddison (2007). Contours of the World Economy, 1–2030 AD. Essays in Macro-Economic History. Oxford University Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-19-922721-1.

- ^ Building Bridges Among the BRICs, p. 125, Robert Crane, Springer, 2014

- ^ Raghu Vamsa v 4.60–75

- ^ Joppen, Charles. Historical atlas of India, for the use of high schools, colleges and private students. Cornell University Library. London; New York: Longmans, Green. pp. map 13.

- ^ "Emperor Shah Jahan and Building Up the Mughal Empire, 1628–58/66", A Short History of the Mughal Empire, I.B.Tauris, 2016, ISBN 978-1-84885-872-5, retrieved 28 June 2024

- ^ Malieckal, Bindu (2009), Johanyak, Debra; Lim, Walter S. H. (eds.), "As Good as Gold", The English Renaissance, Orientalism, and the Idea of Asia, New York: Palgrave Macmillan US, pp. 131–159, doi:10.1057/9780230106222_7, ISBN 978-0-230-10622-2, retrieved 28 June 2024

- ^ Hooja, Rima (2006). A History of Rajasthan. Rupa. p. 454. ISBN 9788129115010.

From Baburs memoirs we learn that Sanga's success against the Mughal advance guard commanded by Abdul Aziz and other forces at Bayana, severely demoralised the fighting spirit of Baburs troops encamped near Sikri.

- ^ Berndl, Klaus (2005). National Geographic Visual History of the World. National Geographic Society. pp. 318–320. ISBN 978-0-7922-3695-5.

- ^ Stein, Burton (2010), A History of India, John Wiley & Sons, p. 159, ISBN 978-1-4443-2351-1 Quote: "The imperial career of the Mughal house is conventionally reckoned to have ended in 1707 when the emperor Aurangzeb, a fifth-generation descendant of Babur, died. His fifty-year reign began in 1658 with the Mughal state seeming as strong as ever or even stronger. But in Aurangzeb's later years the state was brought to the brink of destruction, over which it toppled within a decade and a half after his death; by 1720 imperial Mughal rule was largely finished and an epoch of two imperial centuries had closed."

- ^ Richards, John F. (1995), The Mughal Empire, Cambridge University Press, p. xv, ISBN 978-0-521-56603-2 Quote: "By the latter date (1720) the essential structure of the centralized state was disintegrated beyond repair."

- ^ "Picture of original Mughal rupiya introduced by Sher Shah Suri". Archived from the original on 5 October 2002. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Schmidt, Karl J. (2015). An Atlas and Survey of South Asian History. Routledge. pp. 100–. ISBN 978-1-317-47681-8.

- ^ Pagaza, Ignacio; Argyriades, Demetrios (2009). Winning the Needed Change: Saving Our Planet Earth. IOS Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-58603-958-5.

- ^ Jeffrey G. Williamson & David Clingingsmith, India's Deindustrialization in the 18th and 19th Centuries Archived 29 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Global Economic History Network, London School of Economics

- ^ Om Prakash, "Empire, Mughal", History of World Trade Since 1450, edited by John J. McCusker, vol. 1, Macmillan Reference US, 2006, pp. 237–240, World History in Context. Retrieved 3 August 2017

- ^ Parthasarathi, Prasannan (2011), Why Europe Grew Rich and Asia Did Not: Global Economic Divergence, 1600–1850, Cambridge University Press, p. 2, ISBN 978-1-139-49889-0

- ^ Jeffrey G. Williamson (2011). Trade and Poverty: When the Third World Fell Behind. MIT Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-262-29518-5.

- ^ Richard Maxwell Eaton (1996), The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760, p. 202, University of California Press

Works cited

- Dhere, Ramchandra (2011). Rise of a Folk God: Vitthal of Pandharpur South Asia Research. Oxford University Press, 2011. ISBN 9780199777648.

- Pletcher, Kenneth (2011). The History of India. Britannica Educational Publishing. ISBN 978-1-61530-201-7.

- Radhakrishnan, S.; Moore, C. A. (1957). A Source Book in Indian Philosophy. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-01958-1. Princeton paperback 12th printing, 1989.

- Sewell, Robert (2011). A Forgotten Empire (Vijayanagar). New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-8120601253.

- Stein, Burton (1989). The New Cambridge History of India: Vijayanagara. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-26693-2.

- Olivelle, Patrick (2013), King, Governance, and Law in Ancient India: Kauṭilya's Arthaśāstra, Oxford UK: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199891825, retrieved 20 February 2016