Renewable energy in Vietnam

Vietnam utilizes four main sources of renewable energy: hydroelectricity, wind power, solar power and biomass.[1] At the end of 2018, hydropower was the largest source of renewable energy, contributing about 40% to the total national electricity capacity.[2] In 2020, wind and solar had a combined share of 10% of the country's electrical generation, already meeting the government's 2030 goal, suggesting future displacement of growth of coal capacity.[3] By the end of 2020, the total installed capacity of solar and wind power had reached over 17 GW.[4] Over 25% of total power capacity is from variable renewable energy sources (wind, solar). The commercial biomass electricity generation is currently slow and limited to valorizing bagasse only, but the stream of forest products, agricultural and municipal waste is increasing. The government is studying a renewable portfolio standard that could promote this energy source.

While wind and solar investment remains attractive in Vietnam, existing capacity is under-utilized due to lack of electric transmission capacity and lack of a replacement for the expired feed-in tariff.[5]

The lead-up to the expiration of the initial solar feed-in tariff (FIT) of US$93.5/MWh saw a large increase in Vietnam's installed capacity of solar photovoltaic (PV), from 86 MW in 2018 to about 4.5 GW by the end of June 2019.[6] The number reached about 16.5 GW as of the end of 2020.[4] This represents an annualized installation rate of about 90 W per capita per annum, placing Vietnam among world leaders. As of 2019, Vietnam has the highest installed capacity in Southeast Asia.[6] In 2020, there are 102 solar power plants operating in the country with a total capacity of 6.3 GW. As of 2021, Vietnam has become one of the most successful ASEAN countries in attracting investment in renewable energy and promoting various types of renewables within the country.[7][8]

Vietnam has the largest offshore wind power potential amount ASEAN countries, with over 470 GW technical potential within 200 km of the coast. This is equivalent to about 6 times the country's total installed capacity of any source as of 2022.[9] This offers opportunities for meeting domestic demand as well as exporting other countries such as Singapore.

Hydropower

Since 1975, Vietnam has developed several hydropower projects, including: Son La Hydropower (2400 MW), Lai Chau Hydropower (1200 MW) and Thuy Huoi Quang electricity (560 MW).[10]

By the end of 2018, the country had 818 hydropower projects with a total installed capacity of 23,182 MW [11] and 285 small hydropower plants with a total capacity of about 3,322 MW.[12]

According to the Revised National Power Development Master Plan for the 2011-2020 Period with the Vision to 2030 [13] (also called PDP 7A/ PDP 7 revised):

- "Total capacity of hydropower sources (including small and medium hydroelectricity, pumped-storage hydropower) is about 21,600 MW by 2020, about 24,600 MW by 2025 (pumped-storage hydropower is 1,200 MW) and about 27,800 MW by 2030 (pumped-storage hydropower is 2,400 MW). Electricity production from hydropower sources accounts for about 29.5% in 2020, about 20.5% in 2025 and about 15.5% in 2030."

- "By 2020, the total capacity of power plants will be about 60,000 MW, of which large and medium hydroelectricity and pumped-storage hydropower will be about 30.1%. By 2025, the total capacity will be about 96,500 MW and 49.3% of which will belong to hydropower. By 2030, hydroelectricity will account for 16.9% of the 129,500 MW of total capacity."

Hydropower resources

Vietnam has an exploitable hydropower capacity of about 25-38 GW. 60% of this capacity is concentrated in the north of the country, 27% in the center and 13% in the south.[14][15]

Almost all large hydropower projects with a capacity of over 100 MW have been developed.[14]

The country has over 1,000 identified locations for small hydropower plants, ranging from 100 kW to 30 MW, with a total capacity of over 7,000 MW.

These locations are concentrated mainly in the northern mountains, the South Central Coast and the Central Highlands.[10]

Environmental impact

In October 2018, the Ministry of Industry and Trade and the provincial People's Committees cancelled 474 hydropower projects and 213 potential sites, recognizing that their impact on the environment and society failed to meet the expected benefits in terms of flood control, irrigation and power generation.[16] The majority of these removed projects were located in the mountainous and midland provinces of the North, Central Highlands and Central Coastal provinces, and implemented by private enterprises.[17]

The decision to cancel about half of the projects in the pipeline was motivated by a series of incident with small and medium hydropower, especially in the rainy season.[18] It is a sign that the incentive mechanisms and policies for hydropower have been too efficient at attracting developers. They did not have the built-in barriers to filter out projects with unacceptable risks. The negative outcomes of hydropower development in Vietnam include:

- Livelihood disruption and loss of forests. Building 25 large hydropower projects in the Central Highlands used over 68,000 hectares of land, affecting nearly 26,000 households.[19] For example, the 7.5 MW Dak Ru hydropower plant, which started operating in April 2008 in the Central Highlands, destroyed hundreds of hectares of forest along Dak Ru stream, upsetting the landscape along more than 5 km.

- Dam failure. The Ia Kre 2 hydropower project (5.5MW capacity) in Gia Lai Province was withdrawn on August 8, 2018, after two dams failures in 2013 and 2014. Estimates of damage after two dam failures totalled about 7 billion VND. Also, the second dam failure caused damage to 26 huts and 60 hectares of crops of people who live there.[20]

- Unexpected accidental water discharge. On August 8, 2018, flood discharge of Dong Nai 5 hydropower project happened and the trouble of the discharge valve at Dak Ka hydropower has flooded nearly 1,600 ha of agricultural land, washed away 99 fish rafts of 14 households raising fish on Dong Nai River.[21] On May 23, 2019, Nam Non hydropower unexpectedly discharged water and did not pull the warning whistle as prescribed, this caused 1 person death.[22]

- Perturbation in the downstream water availability and sediment transport. For example, in November 2018, the Lao Cai Provincial People's Committee approved the request to register the two projects on the Red River into its Small and Medium Hydropower Plan: Thai Nien (60 MW) and Bao Ha (40 MW). Downstream provinces along Red River, which include the capital city Hanoi, voiced concerns against the proposed projects.[23]

- Changes in the flood regime. According to the inspection team of Nghe An province, the construction of many hydropower projects in the Ca river basin has greatly changed the river flow, the water recedes more slowly in the flood season, and the flooding period is longer. In December 2018, Nghe An Provincial People's Committee removed 16 hydropower projects from planning and reviewed 1 project.[24]

- Hydropower reservoirs stimulate small intensity earthquakes. From January 2017 to the beginning of August 2018, there were 69 earthquakes with intensity of 2.5 - 3.9 on the Richter scale in the Quang Nam province. Among them, 63 earthquakes occurred in Nam Tra My and Bac Tra My districts, where the Song Tranh 2 hydropower plant was operating and 6 occurred in Phuoc Son district, near the Dak Mi 3 and Dak Mi 4 hydropower facilities.[25] The series of earthquakes near the Song Tranh 2 hydropower plant caused many houses and construction works in Bac Tra My district to crack, causing local people worried about their safety. The press releases of the National Council for Construction Works confirmed that the Song Tranh 2 hydroelectric dam had passed strict quality testing but did not effectively diminish the anxiety of the people. Damages to houses and public buildings were estimated to 3.7 billion VND. Damages to the provincial road is estimated to about VND 20 billion.[26]

Wind energy

By the end of May 31, 2019, 7 wind power plants were in operation, for a national installed capacity of 331 MW.[27] By July 2022, installed capacity had risen to at least 4,000 MW due to the addition of 84 new wind farms.[28]

The power development masterplan PDP 7 revised,[13] published in 2016, stated that Vietnam would aim to have 800 MW of wind power capacity by 2020, 2,000 MW by 2025 and 6,000 MW by 2030.[29] By mid 2019, the number of projects under construction was in line to reach the 2020 target, and the number of projects at the "approved" stage was twice what is needed to meet the 2025 target.

Wind power plants

The Bac Lieu wind farm is a 99 MW project that demonstrated the economic and technical feasibility of large-scale wind power in Vietnam.[30] It is the first project in Asia located on intertidal mudflats. As a first of a kind project, it benefited from a feed-in tariff of 9.8 cents/kWh and preferential financial terms from the US-EXIM bank. While the construction was more complex than an onshore project, it is more accessible than an offshore project, and it captures the benefits of the excellent wind regime without impacting the land used for aquaculture or salt production, according to the project's CDM.

In April 2019, the Trung Nam renewable energy complex was inaugurated.[31] Built in the Ninh Thuan province, it co-locates a wind farm (total investment capital of 4,000 billion VND) and a solar PV power farm (204 MW, total investment capital of 6,000 billion VND). Phase-1 of the wind power plant is operational with a capacity of 39.95 MW. By the fourth quarter of 2019, the second phase of the project will have an additional capacity of 64 MW. Phase 3 will be completed in 2020 with a capacity of 48 MW.[32] The project was completed in time to benefit from an incentive of the feed-in tariff for renewable energy offered by the government. Many other projects were completed in that time window, in excess of the capacity of the transmission network, leading to severe curtailment problems starting in July 2019.

The Thang Long Wind power project proposes to develop large-scale offshore near the Kê Gà area, in the Binh Thuan province. The first phase of the project, for 600 MW, targets to start operating at the end of 2022.[33] The vision is for a total system capacity of about 3,400 MW, at a total investment of nearly US$12 billion, not including investment for connection to the national electricity system.

In 2020 three projects were inaugurated: Dai Phong (40MW) in Binh Thuan, Huong Linh 1 (30MW) in Quang Tri and phase-2 of Trung Nam complex (64MW) in Ninh Thuan.

By July 21, 2021, there are 13 wind power plants with a total capacity of 611.33 MW that have been certified for commercial operation.[34]

The 100 MW Dong Hai-1 intertidal wind farm in Tra Vinh started in January 2022.[35]

Wind resources

Vietnam wind resources are mostly located along its coastline of more than 3,000 km, and in the hills and highlands of the northern and central regions.[37] A World Bank ESMAP study (see the table below) estimated that over 39% of Vietnam's area had annual average wind speed over 6 m/s at a height of 65m, equivalent to a total capacity of 512 GW.[38] It was estimated that over 8% of Vietnam's land area had annual average wind speed over 7 m/s, equivalent to a total capacity of 110 GW.[29]

| Average wind speed | Lower

< 6 m/s |

Medium

6–7 m/s |

Pretty high

7–8 m/s |

High

8–9 m/s |

Very high

> 9 m/s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area (km2) | 197,242 | 100,367 | 25,679 | 2,178 | 111 |

| Area ratio (%) | 60.6 | 30.8 | 7.9 | 0.7 | >0 |

| Potential capacity (MW) | - | 401,444 | 102,716 | 8,748 | 482 |

A comparative study assessed that Vietnam has 8.6% of its land area with "good" to "very good" potential for large wind power stations, while Cambodia has 0.2%, Laos has 2.9%, and Thailand has only 0.2%.[39] In 2021, two offshore wind farms (nearshore 78 and 48 MW) were under construction.[40]

Offshore wind

In May of 2023, the Vietnamese government approved the Power Development Plan 8 (PDP8) which included having 6 gigawatts of offshore windpower online by 2030.[41] However, as of August 2024 there were no offshore wind power stations under construction due to a number of legal hurdles and as a result, at this stage, it is unlikely that the 6 gigawatt goal will be reached.[42] Most recently, the Ministry of Industry and Trade has suggested a pilot offshore wind program to be developed by the state, however, this is only in the planning phase.[43]

Solar energy

Installed capacity

By the end of July 2021, the total solar power installed capacity was about 19,400 MWp (of which nearly 9,300 MWp is rooftop solar power), equivalent to about 16,500 MW, accounting for about 25% of the total installed capacity of all sources in the national power system.

Generous FITs and supporting policies such as tax exemptions are found to be the key proximate drivers of Vietnam's solar PV boom.[4] Underlying drivers include the government's desire to enhance energy self-sufficiency and the public's demand for local environmental quality. A key barrier is limited transmission grid capacity.[6]

Solar resources

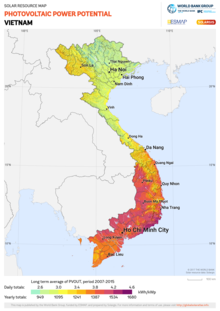

Vietnam has a great potential to develop solar power, especially in the central and more southern regions.

The average number of sunshine hours in the North ranges from 1,500 to 1,700 hours of sunshine per year. Meanwhile, the Central and Southern regions have higher average annual sunshine hours, from 2,000 to 2,600 hours/year.[45][46]

The average daily solar radiation intensity in the north is 3.69 kWh/m2 and the south is 5.9 kWh/m2. The amount of solar radiation depends on the amount of cloud and the atmosphere of each locality. From one region to another, there is significant variation in solar radiation. Radiation intensity in the South is often higher than in the North.[47]

| Region | Average number of sunshine hours | Solar radiation intensity

(kWh/m2/day) |

|---|---|---|

| Northeast | 1,600 – 1,750 | 3.3 – 4.1 |

| Northwest | 1,750 – 1,800 | 4.1 – 4.9 |

| North Central | 1,700 – 2,000 | 4.6 – 5.2 |

| Central Highlands and South Central | 2,000 – 2,600 | 4.9 – 5.7 |

| Southern | 2,200 – 2,500 | 4.3 – 4.9 |

| Average country | 1,700 – 2,500 | 4.6 |

History

According to the prime minister's 2016 energy plan, solar power was expected to reach 850 MW (0.5%) by 2020, about 4,000 MW (1.6%) in 2025 and about 12,000 MW (3.3%) by 2030.[13]

In the first half of 2018, the Ministry of Industry and Trade (MOIT) recorded 272 solar power plant projects in planning with a total capacity of about 17,500 MW, 9 times higher than Hoa Binh hydropower plants and 7 times more than Son La hydropower plant.[48] By the end of 2018, there were about 10,000 MW registered, of which 8100 MW was newly added to the plan, more than 100 projects signed power purchase agreements, and two projects came into operation with a total capacity of about 86 MW.[12]

By the end of June 30, 2019, 82 solar power plants, with a total capacity of about 4,464 MW, were approved and commissioned by the National Electricity Regulatory Center.[49] These projects were entitled to an electricity purchase price (FIT) equivalent to 9.35 US¢/kWh for a period of 20 years under Decision 11/2017/QD-TTg [50] of the Prime Minister. At that time, solar power accounted for 8.28% of the installed capacity of Vietnam's electricity system. Through the end of 2019, the center was expected to put into operation 13 more solar power plants, with a total capacity of 630 MW, bringing the total number of solar power plants in the whole system to 95.[49] The actual installed capacity at the end of 2019 reached almost 5 GW.[3]

Solar power plants

A few large-scale solar power projects have been built in Vietnam:

- In October 2020, the largest 450MW Trung Nam Thuan Nam solar power project in the country and Southeast Asia and the first 500kV transmission and substation system invested by private enterprises was inaugurated after 102 days and nights of implementation.[51]

- In September 2019, Dau Tieng solar power plant cluster officially connected to the national grid with a capacity of 420 MW after more than 10 months of construction, providing about 688 million kWh per year.[52]

- In April 2019, 3 clusters of solar power plants of BIM Group (capacity of 330 MWP) in Ninh Thuan completed commissioning electricity to the national grid system, including BIM-1 power plant with capacity of 30 Mwp; BIM-2 with capacity of 250 Mwp and BIM-3 with capacity of 50 Mwp. The cluster of 3 solar power plants was invested more than 7,000 billion VND, installing more than 1 million solar panels.[53]

- On November 4, 2018, after 9 months of construction, TTC Krong Pa solar power plant with a capacity of 49 MW (69 MWp), and a total investment of more than VND 1,400 billion, which was built in Gia Lai province, was commissioned successfully.[54]

- On September 25, 2018, Phong Dien Solar Power Plant in Thua Thien Hue province completed the commissioning of electricity to the national grid system. This is the first 35 MW solar power plant to be commissioned in Vietnam. It is expected that by 2019, this factory will expand more with the capacity of 29.5 MW with an area of 38.5 hectares, meeting a part of the demand for electricity consumption in the future.[55][needs update]

Tra O lagoon solar power plant project (My Loi commune, Phu My district, Binh Dinh province), with a capacity of 50MWp, was expected to be deployed on a water surface area of around 60 hectares of the lagoon's 1,300 hectares in quarter-II of 2019.[56] However, from mid-2018, during the implementation process, there was a fierce opposition from the local people, preventing investors from building projects due to some big concerns about affecting the ecological environment. These caused death of fish and shrimp under the lagoon (because this is the main income source for the communes surrounding the lagoon) and the water source pollution problem.[57]

Hacom Solar solar power plant project (Phuoc Minh commune, Thuan Nam district, Ninh Thuan province), 50 MWp capacity, was started in April 2019. However, when constructing the factory, the investor (Hacom Solar Energy Co., Ltd) arbitrarily let the vehicles run through people's land. Local people stopped the container trucks from transporting materials into the project and complained that the local authorities and the owner of the solar power plant had to meet with land-owners to negotiate compensation plans for the people because the project has violated people's land.[58]

Biomass energy

As an agricultural country, Vietnam has great potential for biomass energy. The main types of biomass are: energy wood, waste (crop residues), livestock waste, municipal waste and other organic wastes. The biomass energy source can be used by burning directly, or forming a biomass fuel.[10]

Since the Prime Minister issued Decision 24/2014/QD-TTg[59] on mechanisms to support the development of biomass power projects in Vietnam, many agricultural by-products have become an important source of materials, reused to create a large energy source. As in the sugarcane industry, the potential of biomass energy from bagasse is quite large. If utilizing and exploiting bagasse as source thoroughly and effectively, it will contribute considerable electricity output, therefore, contributing to ensuring national energy security.[60]

By November 2018, there were 38 sugar factories in Vietnam using biomass to produce electricity and heat with a total capacity of about 352 MW. Among them, there were only 4 power plants on the grid with a total capacity of 82.51 MW (22.4%), selling 15% of the electricity generated from biomass to the grid at a price of 5.8 US¢/kWh.[61]

Until the end of 2018, 10 more biomass power plants with a total capacity of 212 MW were put into operation.[12]

By February 2020, the total biomass electricity capacity currently in operation is about 400 MW. In which, co-generation of thermal power at sugar mills still accounts for a large proportion: 390 MW with 175 MW of electricity connected to the grid. The rest about 10 MW is from garbage power projects.

The PDP 7A[13] specifies for the development of biomass power: Co-generation in sugar mills, food processing plants, food plants; implement co-firing biomass fuel with coal at coal power plants; electricity generation from solid waste, etc. The proportion of electricity produced from biomass energy sources reaches about 1% by 2020, about 1.2% by 2025 and about 2.1% by 2030.

Some examples of biomass power plants using bagasse:

- On April 2, 2017, KCP Industry Company Limited officially commissioned phase-1 (30MW) of KCP-Phu Yen biomass power plant with a total capacity of 60MW at an investment cost nearly 1,300 billion VND.[62]

- On 4 January 2019, Tuyen Quang Bagasse Biomass Power Plant was officially integrated into the national grid. The plant with a capacity of 25MW has been operating stably, producing 2 million KW, of which 1 million 200 KW has been put into the National Grid, the rest is used for sugar production of the unit.[63]

Solid waste energy (waste-to-energy)

On average, nearly 35,000 tons of urban domestic solid waste and 34,000 tons of rural domestic solid waste are released every day. In big cities like Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, there are 7–8,000 tons of waste per day. The amount of garbage is being wasted due to not being fully utilized for energy production.[64]

As of early 2019, Vietnam had 9.03 MW of waste-to-energy (WtE) electricity. The Go Cat power plant has a capacity of 2.43 MW, Can Tho power generation solid waste treatment plant has a capacity of 6 MW, and an industrial waste treatment plant generating electricity at Nam Son garbage disposal area has a capacity of 0.6 MW.[65]

On February 18, 2019, Hau Giang WtE power plant project (Hau Giang province) will have a capacity of 12 MW, of which phase-1 (6 MW capacity) will be put into operation in 2019 and phase-2 (6 MW capacity) will be run in 2024. This plant is connected to the national electricity system by 22 kV voltage. Phu Tho waste WtE power plant project (Phu Tho province) will have a capacity of 18 MW, of which phase-1 (9 MW capacity) will be put into operation in 2020, and phase 2 (9 MW) will be commissioned in the year 2026. This plant is connected to the national electricity system by 110 kV voltage.[65]

According to the Decision 2068/QD-TTg [66] on Approving the Viet Nam's Renewable Energy Development Strategy up to 2030 with an outlook to 2050:

- The rate of urban solid waste for energy targets is expected to increase up to 30% by 2020, and approximately 70% by 2030. Most urban solid waste will be used for energy production by 2050.

Geothermal energy

Vietnam has more than 250 hot water points widely distributed across the country, including 43 hot spots (> 61 degrees), the highest point of exit with 100 degrees is located in Le Thuy (Quang Binh).[67] Of the total 164 sources of geothermal in the northern midlands and mountains of Vietnam, up to 18 sources with surface temperatures > 53 degrees can allow the application of power generation purposes.[68] The geothermal potential throughout the territory of Vietnam is estimated at 300 MW.[10]

Tidal energy

In Vietnam, the tidal energy potential is not large, can only reach 4GW capacity in the coastal areas of the Mekong Delta. However, the large potential area that has not been studied is the coastal waters of Quang Ninh - Hai Phong, especially Ha Long Bay and Bai Tu Long, where the tidal range is high (> 4m), and many islands do dikes for water tanks in coastal lakes and bays.[69]

Another report called "Renewable energy on the sea and development orientation in Vietnam"[70] raised the potential of tidal energy: Concentrated in the northern part of the Gulf of Tonkin and the Southeast coastal estuaries. Potential theoretical calculations show that tidal power can reach 10 GW.

Renewable energy support policies

To encourage renewable energy development, the Government has set a price to buy electricity from renewable energy projects (Feed-in tariff-FIT price). Below is a summary of the current support mechanisms for renewable energy types:

| RE type | Technology | Price type | Electricity price |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small hydroelectricy | Power generation | Avoided cost is published annually | 598-663 VND/kWh (by time, region, season)

302-320 VND/kWh (excess electricity compared to the contract) 2158 VND/kW (capacity price) |

| Wind power | Power generation | FIT price 20 years | 8.5 US¢/kWh (on shore) and 9.8 US¢/kWh (off shore) |

| Solar power | Power generation | FIT price 20 years | 7.69 US¢/kWh (floating)

7.09 US¢/kWh (ground) 8.38 US¢/kWh (rooftop) |

| Biomass energy | Cogeneration

Power generation |

Avoided cost is published annually | 5.8 US¢/kWh (for cogeneration)

7.5551 US¢/kWh (North) 7.3458 US¢/kWh (Central) 7.4846 US¢/kWh (South) |

| Waste to energy | Direct burning

Burning of gases from landfills |

FIT price 20 years

FIT price 20 years |

10.5 US¢/kWh

7.28 US¢/kWh |

According to one study, FITs and reverse auctions appear to be suitable for the next phase of Vietnam's renewable pricing.[6] Regulations could also be revised to enable private sector investment in upgrading transmission grids. Reforms to administrative procedures, strengthening the bankability of Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) by reducing off-take risks, reducing fossil fuel subsidies, and introducing a carbon price are also attractive options. The government could also consider enacting a law on renewable energy to provide a comprehensive and stable legal framework.[6]

Carbon pricing is also expected to boost the renewable energy uptake. Vietnam had also legalized an emission trading scheme in the revised Law on Environmental Protection 2020. Preparation including piloting is planned for 2022-2027 and the roll out is expected around 2027.[71]

See also

References

- ^ "VIETNAM RENEWABLE ENERGY OPTIONS". 27 September 2021.

- ^ Diệu Thúy (2019-06-21). "Phát triển năng lượng tái tạo- Bài 1: Cơ hội cho điện gió và điện mặt trời". bnews.vn.

- ^ a b "Vietnam grapples with an unexpected surge in solar power, Vietnam grapples with an unexpected surge in solar power". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2020-01-28.

- ^ a b c Do, Thang Nam; Burke, Paul J.; Nguyen, Hoang Nam; Overland, Indra; Suryadi, Beni; Swandaru, Akbar; Yurnaidi, Zulfikar (2021-12-01). "Vietnam's solar and wind power success: Policy implications for the other ASEAN countries". Energy for Sustainable Development. 65: 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.esd.2021.09.002. hdl:1885/248804. ISSN 0973-0826.

- ^ Le, Lam. "After renewables frenzy, Vietnam's solar energy goes to waste". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2022-09-02.

- ^ a b c d e Do, Thang Nam; Burke, Paul J.; Baldwin, Kenneth G.H.; Nguyen, Chinh The (September 2020). "Underlying drivers and barriers for solar photovoltaics diffusion: The case of Vietnam". Energy Policy. 144: 111561. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111561. hdl:1885/206307. S2CID 225245522.

- ^ Overland, Indra; Sagbakken, Haakon Fossum; Chan, Hoy-Yen; Merdekawati, Monika; Suryadi, Beni; Utama, Nuki Agya; Vakulchuk, Roman (December 2021). "The ASEAN climate and energy paradox". Energy and Climate Change. 2: 100019. doi:10.1016/j.egycc.2020.100019. hdl:11250/2734506.

- ^ Vakulchuk, Roman; Chan, Hoy-Yen; Kresnawan, Muhammad Rizki; Merdekawati, Monika; Overland, Indra; Sagbakken, Haakon Fossum; Suryadi, Beni; Utama, Nuki Agya; Yurnaidi, Zulfikar (2020). "Vietnam: Six Ways to Keep Up the Renewable Energy Investment Success". Norwegian Institute of International Affairs. JSTOR resrep26568.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Do, Thang Nam; Burke, Paul, J.; Hughes, Llewelyn; Ta, Dinh Thi (2022). "Policy options for offshore wind power in Vietnam". Marine Policy. 141 (105080): 105080. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105080. hdl:1885/275544. S2CID 248957321.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Nguyễn, Mạnh Hiến (2019-02-18). "Tổng quan tiềm năng và triển vọng phát triển năng lượng tái tạo Việt Nam". Năng lượng Việt Nam.

- ^ Dịch Phong (2019-07-22). "Điện than đứng trước nguy cơ "hụt hơi" so với điện mặt trời và điện khí". baoxaydung.com.vn.

- ^ a b c Thảo Miên (2019-03-12). "Việt Nam ưu tiên phát triển năng lượng tái tạo". Thời báo Tài Chính.

- ^ a b c d Nguyễn, Tấn Dũng (2016-03-18). "PM Decision 428/QĐ-TTg on the Approval of the Revised National Power Development Master Plan for the Period of 2011-2020 with the Vision to 2030". vepg.vn.

- ^ a b TCĐL Chuyên đề Quản lý & Hội nhập (2019-06-20). "Khái quát về thủy điện Việt Nam". evn.com.vn.

- ^ Hiếu Công (2018-12-11). "Việt Nam nói không với nhiệt điện than, được không?". news.zing.vn.

- ^ Phan Trang (2018-10-30). "Bộ Công Thương kiên quyết "xoá sổ" gần 500 dự án thuỷ điện nhỏ". baochinhphu.vn.

- ^ Khánh Vũ (2018-07-27). "Đã có kịch bản bảo đảm an toàn hồ Hòa Bình, Sơn La". laodong.vn.

- ^ Mạnh Cường (2017-10-05). "Để thủy điện và năng lượng tái tạo phát triển an toàn, bền vững". qdnd.vn.

- ^ Lê, Thị Thanh Hà (2018-02-28). "Tác động của thủy điện tới môi trường ở Tây Nguyên hiện nay". tapchicongsan.org.vn.

- ^ Phạm Hoàng (2018-08-09). "Sau 2 lần vỡ đập, Thủy điện Ia Krêl 2 bị thu hồi dự án". dantri.com.vn.

- ^ Vũ Hội (2019-08-10). "Thủy điện ngưng xả tràn, lũ ở Đồng Nai đang xuống". plo.vn.

- ^ Doãn Hòa (2019-07-11). "Khởi tố vụ nhà máy thủy điện xả lũ làm chết người". tuoitre.vn.

- ^ baodatviet.vn (2019-06-03). "Thủy điện trên sông Hồng: Nguy hại, không nên đặt ra".

- ^ NANGLUONG VIETNAM (2018-12-12). "Nghệ An loại bỏ 16 dự án thủy điện nhỏ ra khỏi quy hoạch".

- ^ Khánh Chi (2018-09-26). "Quảng Nam: Lại tiếp tục xảy ra động đất gần thủy điện Sông Tranh 2". baovanhoa.vn.

- ^ GreenID (August 2013). "Phân tích chi phí và rủi ro môi trường-xã hội của đập thủy điện–với trường hợp điển hình là nhà máy thủy điện Sông Tranh 2" (PDF). undp.org.

- ^ Mai Thắng (2019-06-11). "Thúc đẩy thị trường điện gió tại Việt Nam phát triển". Năng Lượng Việt Nam.

- ^ "WFO Có 84 dự án điện gió với gần 4.000MW kịp vận hành thương mại". 3 November 2021.

- ^ a b c Ngân Quyên (2019-02-21). "Tiềm năng phát triển điện gió". EVNHANOI.

- ^ Hong Thai Vo.; Viet Trung Le; Thi Thu Hang Cao (2019). "Offshore Wind Power in Vietnam: Lessons Learnt from Phu Quy and Bac Lieu Wind Farms". Acta Scientific Agriculture 3.2. 1st Vietnam Symposium on Advances in Offshore Engineering. pp. 26–29.

- ^ "Home - Trungnam Group".

- ^ VPMT (2019-04-28). "Trung Nam Group khánh thành tổ hợp điện gió, điện mặt trời tại Ninh Thuận". thoibaonganhang.vn.

- ^ Vũ Dung (2019-07-18). "Gỡ khó cho điện gió". qdnd.vn.

- ^ "13 nhà máy điện gió đã vào vận hành thương mại". moit.gov.vn. 23 July 2021. Retrieved 2022-10-18.

- ^ "Trungnam starts operation of its intertidal offshore wind farm in Vietnam". www.windtech-international.com. 21 January 2022.

- ^ "Global Wind Atlas".

- ^ Chí Nhân (2019-03-27). "Đề xuất phát triển điện gió ngoài khơi". Báo Thanh Niên.

- ^ TrueWind Solutions, LLC (2001-09-01). "Wind energy resource atlas of Southeast Asia (English)". documents.worldbank.org.

- ^ Tô Minh Châu (2017-12-09). "Wind energy in Vietnam and proposed development direction". vjol.info.

- ^ "All Foundations Installed at Vietnam's Hiep Thanh and Tra Vinh V1-2 Nearshore Wind Farms". Offshore Wind. 27 August 2021. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021.

- ^ the-shiv (2024-05-16). "Electricity in Vietnam for Foreign Investors 2024". the-shiv. Retrieved 2024-08-28.

- ^ Barnes, Mark (2024-05-07). "Vietnam's Offshore Wind Power Holdup: Unpacked 2024". the-shiv. Retrieved 2024-08-28.

- ^ the-shiv (2024-07-23). "Offshore wind in Vietnam should to be developed by state first: MoIT". the-shiv. Retrieved 2024-08-28.

- ^ "Global Solar Atlas".

- ^ Tấn Lực (2019-04-19). "Miền Trung, miền Nam có nhiều tiềm năng điện mặt trời áp mái". Tuổi Trẻ Online.

- ^ Tạ Văn Đa, Hoàng Xuân Cơ, Đinh Mạnh Cường, Đặng Thị Hải Linh, Đặng Thanh An, Lê Hữu Hải (2016-09-06). "Khả năng khai thác năng lượng mặt trời phục vụ các hoạt động đời sống ở miền Trung Việt Nam".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Vũ Phong Solar (2016-04-11). "Cường độ bức xạ năng lượng mặt trời tại các khu vực Việt Nam". solarpower.vn.

- ^ Từ Vũ (2019-07-10). "Phát triển năng lượng mặt trời tại Việt Nam là cần thiết, nhưng chớ quên những yếu tố bất cập này". SOHA.VN.

- ^ a b M. Tâm (2019-07-01). "Đến 30/6/2019: Trên 4.460 MW điện mặt trời đã hòa lưới". EVN - Tập đoàn điện lực Việt Nam.

- ^ Nguyễn, Xuân Phúc (2017-04-11). "Decision No. 11/2017/QĐ-TTg mechanism for encouragement of development of solar power in Vietnam 2017". vanbanphapluat.co. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- ^ "Khánh thành dự án điện mặt trời lớn nhất Đông Nam Á tại Ninh Thuận". TUOI TRE ONLINE (in Vietnamese). 2020-10-12. Retrieved 2021-09-21.

- ^ "Khánh thành cụm nhà máy điện năng lượng mặt trời lớn nhất Đông Nam Á". TUOI TRE ONLINE (in Vietnamese). 2019-09-07. Retrieved 2021-09-21.

- ^ Như Loan (2019-04-27). "BIM Group khánh thành cụm 3 nhà máy điện mặt trời, tổng công suất 330 MWP". Đầu Tư Online.

- ^ Nam Bình (2018-02-12). "Nhà máy điện mặt trời TTC Krông Pa công suất 49 MW (69 MWp)". Báo Thanh Niên online.

- ^ Thùy Vinh (2018-04-10). "Khánh thành nhà máy điện mặt trời 35 MW đầu tiên tại Việt Nam". Đầu tư online.

- ^ Nguyễn Tri (2019-04-02). "Dự án Nhà máy điện mặt trời đầm Trà Ổ: Người dân tiếp tục phản đối". laodong.vn.

- ^ BBC VN (2019-05-11). "Bình Định: Dân xô xát với công an phản đối điện mặt trời ở Đầm Trà Ổ". BBC News Tiếng Việt.

- ^ Minh Trân (2019-06-20). "Dân đặt hàng trăm đá tảng chặn xe dự án nhà máy điện mặt trời". tuoitre.vn.

- ^ Nguyễn, Tấn Dũng (2014-03-24). "Decision 24/ 2014/QĐ-TTg on the support mechanism for the development of biomass power projects in Vietnam" (PDF). gizenergy.org.vn.

- ^ Bích Hồng (2019-03-17). "Nguồn cung dồi dào từ phụ phẩm cho ngành điện". dantocmiennui.vn.

- ^ GGGI & GIZ (November 2018). "Tạo sự hấp dẫn cho năng lượng sinh khối trong ngành mía đường ở Việt Nam" (PDF). gggi.org.

- ^ Thế Lập (2017-04-02). "Nhà máy điện sinh khối KCP-Phú Yên chính thức hòa lưới điện quốc gia". bnews.vn.

- ^ TTV (2019-01-05). "Nhà máy Điện sinh khối mía đường Tuyên Quang hòa lưới điện quốc gia". hamyen.org.vn.

- ^ Quyên Lưu (2017-08-19). "Việt Nam còn nhiều tiềm năng biến rác thải thành nguyên liệu cho sản xuất năng lượng". moit.gov.vn.

- ^ a b Phương Trần (2019-02-25). "Bổ sung 2 dự án điện rác vào Quy hoạch phát triển Điện lực Quốc gia". EVN - Tập đoàn điện lực Việt Nam.

- ^ Nguyễn, Tấn Dũng (2015-11-25). "Decision 2068/QD-TTg on Approving the Viet Nam's Renewable Energy Development Strategy up to 2030 with an outlook to 2050" (PDF). mzv.cz.

- ^ Nguyễn Văn Phơn, Đoàn Văn Tuyến (2017-03-16). "Địa nhiệt ứng dụng". repository.vnu.edu.vn.

- ^ Trần Trọng Thắng, Vũ Văn Tích, Đặng Mai, Hoàng Văn Hiệp, Phạm Hùng Thanh, Phạm Xuân Ánh (2016-10-28). "Một số kết quả đánh giá tiềm năng năng lượng của các nguồn địa nhiệt triển vọng ở vùng trung du và miền núi phía Bắc Việt Nam". js.vnu.edu.vn.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Văn Hào (2017-12-23). "Năng lượng mặt trời, gió, sóng biển, thủy triều: Tiềm năng khổng lồ của biển đảo Việt Nam". thethaovanhoa.vn.

- ^ Dư Văn Toán (2018-10-12). "Năng lượng tái tạo trên biển và định hướng phát triển tại Việt Nam". researchgate.net.

- ^ Do, Thang Nam; Burke, Paul J. (2021-12-01). "Carbon pricing in Vietnam: Options for adoption". Energy and Climate Change. 2: 100058. doi:10.1016/j.egycc.2021.100058. hdl:1885/250449. ISSN 2666-2787. S2CID 243844301.