Gas tungsten arc welding

Gas tungsten arc welding (GTAW, also known as tungsten inert gas welding or TIG, and heliarc welding when helium is used) is an arc welding process that uses a non-consumable tungsten electrode to produce the weld. The weld area and electrode are protected from oxidation or other atmospheric contamination by an inert shielding gas (argon or helium). A filler metal is normally used, though some welds, known as 'autogenous welds', or 'fusion welds' do not require it. A constant-current welding power supply produces electrical energy, which is conducted across the arc through a column of highly ionized gas and metal vapors known as a plasma.

The process grants the operator greater control over the weld than competing processes such as shielded metal arc welding and gas metal arc welding, allowing stronger, higher-quality welds. However, TIG welding is comparatively more complex and difficult to master, and furthermore, it is significantly slower than most other welding techniques.

TAG welding (short for "tungsten argon gas welding")[citation needed] was the name given in the early 1970s to the then-novel and revolutionary method of rod welding previously problematic metals. TAG welding was then the use of a tungsten-tipped, arc-creating welding machine. The tip was centred in a shroud that fed argon gas around the tungsten tip to prevent the composition of the weld becoming oxidised and fragile. TAG welding used rods of a metal suitable for the material to be welded permanently together. The rods could be a metal coated in oil to prevent the rod oxidising if needed or in more complicated welding of metals the rod would be coated in a "flux" that was not an active flux but a method of protecting the welding rods from oxidisation during storage (the major examples of this were rods for welding; pure aluminium, duralumin, magnesium/aluminium alloy and stainless steel rods used for repairing ultra high grade carbon steel as in WW2 Sherman tanks). At this time the most prevalent use of TAG welding is in the production of higher-end aluminium alloy bicycles; these welds are clearly visible as ripples in the welded joint.[citation needed] Other than mostly bicycle production, TAG has been surpassed by the use of tungsten alloy tips and argon gas combined with other inert gases. TAG welding rods are now highly specific project metal alloy rods or more frequently mass production flexible "flux" cable/wire fed drum machines. These developments have rendered the TAG name as not specific and have fallen out of favour although the basic process remains the same.[citation needed]

TIG welding is most commonly used to weld thin sections of stainless steel and non-ferrous metals such as aluminium, magnesium, and copper alloys.

A related process, plasma arc welding, uses a slightly different welding torch to create a more focused welding arc and as a result is often automated.[1]

Development

After the discovery of the short pulsed electric arc in 1801 by Humphry Davy[2][3] and of the continuous electric arc in 1802 by Vasily Petrov,[3][4] arc welding developed slowly. C. L. Coffin had the idea of welding in an inert gas atmosphere in 1890, but even in the early 20th century, welding non-ferrous materials such as aluminum and magnesium remained difficult because these metals react rapidly with the air, resulting in porous, dross-filled welds.[5] Processes using flux-covered electrodes did not satisfactorily protect the weld area from contamination. To solve the problem, bottled inert gases were used in the beginning of the 1930s. A few years later, a direct current, gas-shielded welding process emerged in the aircraft industry for welding magnesium.[6]

In early 1940s Northrop Aircraft was developing an experimental aircraft from magnesium designated XP-56, for which Vladimir Pavlecka, Tom Piper and Russell Meredith developed a welding process named Heliarc because it used a tungsten electrode arc and helium as a shielding gas (the torch design was patented by Meredith in 1941).[7] It is now often referred to as tungsten inert gas welding (TIG), especially in Europe, but the American Welding Society's official term is gas tungsten arc welding (GTAW). Linde Air Products developed a wide range of air-cooled and water-cooled torches, gas lenses to improve shielding, and other accessories that increased the use of the process. Initially, the electrode overheated quickly and, despite tungsten's high melting temperature, particles of tungsten were transferred to the weld.[6] To address this problem, the polarity of the electrode was changed from positive to negative, but the change made it unsuitable for welding many non-ferrous materials. Finally, the development of alternating current units made it possible to stabilize the arc and produce high quality aluminum and magnesium welds.[6][8]

Developments continued during the following decades. Linde developed water-cooled torches that helped prevent overheating when welding with high currents.[9] During the 1950s, as the process continued to gain popularity, some users turned to carbon dioxide as an alternative to the more expensive welding atmospheres consisting of argon and helium, but this proved unacceptable for welding aluminum and magnesium because it reduced weld quality, so it is rarely used with GTAW today.[10] The use of any shielding gas containing an oxygen compound, such as carbon dioxide, quickly contaminates the tungsten electrode, making it unsuitable for the TIG process.[11] In 1953, a new process based on GTAW was developed, called plasma arc welding. It affords greater control and improves weld quality by using a nozzle to focus the electric arc, but is largely limited to automated systems, whereas GTAW remains primarily a manual, hand-held method.[10] Development within the GTAW process has continued as well, and today a number of variations exist. Among the most popular are the pulsed-current, manual programmed, hot-wire, dabber, and increased penetration GTAW methods.[12]

Operation

Manual gas tungsten arc welding is a relatively difficult welding method, due to the coordination required by the welder. Similar to torch welding, GTAW normally requires two hands, since most applications require that the welder manually feed a filler metal into the weld area with one hand while manipulating the welding torch in the other. Maintaining a short arc length, while preventing contact between the tungsten electrode and the workpiece, is also important.[13]

To strike the welding arc, a high-frequency generator (similar to a Tesla coil) provides an electric spark. This spark is a conductive path for the welding current through the shielding gas and allows the arc to be initiated while the electrode and the workpiece are separated, typically about 1.5–3 mm (0.06–0.12 in) apart.[14]

Once the arc is struck, the welder moves the torch in a small circle to create a welding pool, the size of which depends on the size of the electrode and the amount of current. While maintaining a constant separation between the electrode and the workpiece, the operator then moves the torch back slightly and tilts it backward about 10–15 degrees from vertical. Filler metal is added manually to the front end of the weld pool as it is needed.[14]

Welders often develop a technique of rapidly alternating between moving the torch forward (to advance the weld pool) and adding filler metal. The filler rod is withdrawn from the weld pool each time the electrode advances, but it is always kept inside the gas shield to prevent oxidation of its surface and contamination of the weld. Filler rods composed of metals with a low melting temperature, such as aluminum, require that the operator maintain some distance from the arc while staying inside the gas shield. If held too close to the arc, the filler rod can melt before it makes contact with the weld puddle. As the weld nears completion, the arc current is often gradually reduced to allow the weld crater to solidify and prevent the formation of crater cracks at the end of the weld.[15][16]

The physics of GTAW involves several complex processes, including thermodynamics, plasma physics, and fluid dynamics. The non-consumable tungsten electrode can be operated as a Cathode or Anode and is used to produce an electric arc between the electrode and the workpiece. In order to initially create the arc, the welding area is flooded with inert gas and a high strike voltage (typically 1 kV per 1 mm) is generated by the welding machine to overcome the electric resistivity of the atmosphere surrounding the welding area. With the arc established, the voltage is lowered and current flows between the work piece and electrode. Despite the high temperatures of this electric arc, the main heat transfer mechanism in GTAW is the joule heating resulting from this current flow.[17]

Safety

Welders wear protective clothing, including light and thin leather gloves and protective long sleeve shirts with high collars, to avoid exposure to strong ultraviolet light. Due to the absence of smoke in GTAW, the electric arc light is not covered by fumes and particulate matter as in stick welding or shielded metal arc welding, and thus is a great deal brighter, subjecting operators to strong ultraviolet light. The welding arc has a different range and strength of UV light wavelengths from sunlight, but the welder is very close to the source and the light intensity is very strong. Potential arc light damage includes accidental flashes to the eye or arc eye and skin damage similar to strong sunburn. Operators wear opaque helmets with dark eye lenses and full head and neck coverage to prevent this exposure to UV light. Modern helmets often feature a liquid crystal-type face plate that self-darkens upon exposure to the bright light of the struck arc. Transparent welding curtains, made of a strongly colored polyvinyl chloride plastic film, are often used to shield nearby workers and bystanders from exposure to the UV light from the electric arc.[18]

Welders are also often exposed to dangerous gases and particulate matter. While the process doesn't produce smoke, the brightness of the arc in GTAW can break down surrounding air to form ozone and nitric oxides. The ozone and nitric oxides react with lung tissue and moisture to create nitric acid and ozone burn. Ozone and nitric oxide levels are moderate, but exposure duration, repeated exposure, and the quality and quantity of fume extraction, and air change in the room must be monitored. Welders who do not work safely can contract emphysema and oedema of the lungs, which can lead to early death. Similarly, the heat from the arc can cause poisonous fumes to form from cleaning and degreasing materials. Cleaning operations using these agents should not be performed near the site of welding, and proper ventilation is necessary to protect the welder.[18]

Applications

While the aerospace industry is one of the primary users of gas tungsten arc welding, the process is used in a number of other areas. Many industries use GTAW for welding thin workpieces, especially nonferrous metals. It is used extensively in the manufacture of space vehicles and is also frequently employed to weld small-diameter, thin-wall tubing such as that used in the bicycle industry. In addition, GTAW is often used to make root or first-pass welds for piping of various sizes. In maintenance and repair work, the process is commonly used to repair tools and dies, especially components made of aluminum and magnesium.[19] Because the weld metal is not transferred directly across the electric arc like most open arc welding processes, a vast assortment of welding filler metal is available to the welding engineer. In fact, no other welding process permits the welding of so many alloys in so many product configurations. Filler metal alloys, such as elemental aluminum and chromium, can be lost through the electric arc from volatilization. This loss does not occur with the GTAW process. Because the resulting welds have the same chemical integrity as the original base metal or match the base metals more closely, GTAW welds are highly resistant to corrosion and cracking over long time periods, making GTAW the welding procedure of choice for critical operations like sealing spent nuclear fuel canisters before burial.[20]

Quality

Gas tungsten arc welding, because it affords greater control over the weld area than other welding processes, can produce high-quality welds when performed by skilled operators. Maximum weld quality is assured by maintaining cleanliness—all equipment and materials used must be free from oil, moisture, dirt and other impurities, as these cause weld porosity and consequently a decrease in weld strength and quality. To remove oil and grease, alcohol or similar commercial solvents may be used, while a stainless steel wire brush or chemical process can remove oxides from the surfaces of metals like aluminum. Rust on steels can be removed by first grit blasting the surface and then using a wire brush to remove any embedded grit. These steps are especially important when negative polarity direct current is used, because such a power supply provides no cleaning during the welding process, unlike positive polarity direct current or alternating current.[21] To maintain a clean weld pool during welding, the shielding gas flow should be sufficient and consistent so that the gas covers the weld and blocks impurities in the atmosphere. GTAW in windy or drafty environments increases the amount of shielding gas necessary to protect the weld, increasing the cost and making the process unpopular outdoors.[22]

The level of heat input also affects weld quality. Low heat input, caused by low welding current or high welding speed, can limit penetration and cause the weld bead to lift away from the surface being welded. If there is too much heat input, however, the weld bead grows in width while the likelihood of excessive penetration and spatter (emission of small, unwanted droplets of molten metal) increases. Additionally, if the welding torch is too far from the workpiece the shielding gas becomes ineffective, causing porosity within the weld. This results in a weld with pinholes, which is weaker than a typical weld.[22]

If the amount of current used exceeds the capability of the electrode, tungsten inclusions in the weld may result. Known as tungsten spitting, this can be identified with radiography and can be prevented by changing the type of electrode or increasing the electrode diameter. In addition, if the electrode is not well protected by the gas shield or the operator accidentally allows it to contact the molten metal, it can become dirty or contaminated. This often causes the welding arc to become unstable, requiring that the electrode be ground with a diamond abrasive to remove the impurity.[22]

Equipment

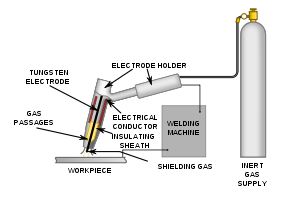

The equipment required for the gas tungsten arc welding operation includes a welding torch utilizing a non-consumable tungsten electrode, a constant-current welding power supply, and a shielding gas source.

Welding torch

GTAW welding torches are designed for either automatic or manual operation and are equipped with cooling systems using air or water. The automatic and manual torches are similar in construction, but the manual torch has a handle while the automatic torch normally comes with a mounting rack. The angle between the centerline of the handle and the centerline of the tungsten electrode, known as the head angle, can be varied on some manual torches according to the preference of the operator. Air cooling systems are most often used for low-current operations (up to about 200 A), while water cooling is required for high-current welding (up to about 600 A). The torches are connected with cables to the power supply and with hoses to the shielding gas source and where used, the water supply.[23]

The internal metal parts of a torch are made of hard alloys of copper or brass so it can transmit current and heat effectively. The tungsten electrode must be held firmly in the center of the torch with an appropriately sized collet, and ports around the electrode provide a constant flow of shielding gas. Collets are sized according to the diameter of the tungsten electrode they hold. The body of the torch is made of heat-resistant, insulating plastics covering the metal components, providing insulation from heat and electricity to protect the welder.[23]

The size of the welding torch nozzle depends on the amount of shielded area desired. The size of the gas nozzle depends upon the diameter of the electrode, the joint configuration, and the availability of access to the joint by the welder. The inside diameter of the nozzle is preferably at least three times the diameter of the electrode, but there are no hard rules. The welder judges the effectiveness of the shielding and increases the nozzle size to increase the area protected by the external gas shield as needed. The nozzle must be heat resistant and thus is normally made of alumina or a ceramic material, but fused quartz, a high purity glass, offers greater visibility. Devices can be inserted into the nozzle for special applications, such as gas lenses or valves to improve the control shielding gas flow to reduce turbulence and the introduction of contaminated atmosphere into the shielded area. Hand switches to control welding current can be added to the manual GTAW torches.[23]

Power supply

Gas tungsten arc welding uses a constant current power source, meaning that the current (and thus the heat flux) remains relatively constant, even if the arc distance and voltage change. This is important because most applications of GTAW are manual or semiautomatic, requiring that an operator hold the torch. Maintaining a suitably steady arc distance is difficult if a constant voltage power source is used instead since it can cause dramatic heat variations and make welding more difficult.[24]

The preferred polarity of the GTAW system depends largely on the type of metal being welded. Direct current with a negatively charged electrode (DCEN) is often employed when welding steels, nickel, titanium, and other metals. It can also be used in automatic GTAW of aluminum or magnesium when helium is used as a shielding gas.[25] The negatively charged electrode generates heat by emitting electrons, which travel across the arc, causing thermal ionization of the shielding gas and increasing the temperature of the base material. The ionized shielding gas flows toward the electrode, not the base material, and this can allow oxides to build on the surface of the weld.[25] Direct current with a positively charged electrode (DCEP) is less common, and is used primarily for shallow welds since less heat is generated in the base material. Instead of flowing from the electrode to the base material, as in DCEN, electrons go the other direction, causing the electrode to reach very high temperatures.[25] To help it maintain its shape and prevent softening, a larger electrode is often used. As the electrons flow toward the electrode, ionized shielding gas flows back toward the base material, cleaning the weld by removing oxides and other impurities and thereby improving its quality and appearance.[25]

Alternating current, commonly used when welding aluminum and magnesium manually or semi-automatically, combines the two direct currents by making the electrode and base material alternate between positive and negative charge. This causes the electron flow to switch directions constantly, preventing the tungsten electrode from overheating while maintaining the heat in the base material.[25] Surface oxides are still removed during the electrode-positive portion of the cycle and the base metal is heated more deeply during the electrode-negative portion of the cycle. Some power supplies enable operators to use an unbalanced alternating current wave by modifying the exact percentage of time that the current spends in each state of polarity, giving them more control over the amount of heat and cleaning action supplied by the power source.[25] In addition, operators must be wary of rectification, in which the arc fails to reignite as it passes from straight polarity (negative electrode) to reverse polarity (positive electrode). To remedy the problem, a square wave power supply can be used, as can high-frequency to encourage arc stability.[25]

Electrode

| ISO Class |

ISO Color |

AWS Class |

AWS Color |

Alloy[26] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WP | Green | EWP | Green | None |

| WC20 | Gray | EWCe-2 | Orange | ~2% CeO2 |

| WL10 | Black | EWLa-1 | Black | ~1% La2O3 |

| WL15 | Gold | EWLa-1.5 | Gold | ~1.5% La2O3 |

| WL20 | Sky-blue | EWLa-2 | Blue | ~2% La2O3 |

| WT10 | Yellow | EWTh-1 | Yellow | ~1% ThO2 |

| WT20 | Red | EWTh-2 | Red | ~2% ThO2 |

| WT30 | Violet | ~3% ThO2 | ||

| WT40 | Orange | ~4% ThO2 | ||

| WY20 | Blue | ~2% Y2O3 | ||

| WZ3 | Brown | EWZr-1 | Brown | ~0.3% ZrO2 |

| WZ8 | White | ~0.8% ZrO2 |

The electrode used in GTAW is made of tungsten or a tungsten alloy, because tungsten has the highest melting temperature among pure metals, at 3,422 °C (6,192 °F). As a result, the electrode is not consumed during welding, though some erosion (called burn-off) can occur. Electrodes can have either a clean finish or a ground finish—clean finish electrodes have been chemically cleaned, while ground finish electrodes have been ground to a uniform size and have a polished surface, making them optimal for heat conduction. The diameter of the electrode can vary between 0.5 and 6.4 millimetres (0.02 and 0.25 in), and their length can range from 75 to 610 millimetres (3.0 to 24.0 in).

A number of tungsten alloys have been standardized by the International Organization for Standardization and the American Welding Society in ISO 6848 and AWS A5.12, respectively, for use in GTAW electrodes, and are summarized in the adjacent table.

- Pure tungsten electrodes (classified as WP or EWP) are general purpose and low cost electrodes. They have poor heat resistance and electron emission. They find limited use in AC welding of e.g. magnesium and aluminum.[27]

- Thorium oxide (or thoria) alloy electrodes offer excellent arc performance and starting, making them popular general purpose electrodes. However, thorium is somewhat radioactive, making inhalation of vapors and dust a health risk, and disposal an environmental risk.[28]

- Cerium oxide (or ceria) as an alloying element improves arc stability and ease of starting while decreasing burn-off. Cerium addition is not as effective as thorium but works well,[29] and cerium is not radioactive.[28]

- An alloy of lanthanum oxide (or lanthana) has a similar effect as cerium, and is also not radioactive.[28]

- Electrodes containing zirconium oxide (or zirconia) increase the current capacity while improving arc stability and starting while also increasing electrode life.[28]

Filler metals are also used in nearly all applications of GTAW, the major exception being the welding of thin materials. Filler metals are available with different diameters and are made of a variety of materials. In most cases, the filler metal in the form of a rod is added to the weld pool manually, but some applications call for an automatically fed filler metal, which often is stored on spools or coils.[30]

Shielding gas

As with other welding processes such as gas metal arc welding, shielding gases are necessary in GTAW to protect the welding area from atmospheric gases such as nitrogen and oxygen, which can cause fusion defects, porosity, and weld metal embrittlement if they come in contact with the electrode, the arc, or the welding metal. The gas also transfers heat from the tungsten electrode to the metal, and it helps start and maintain a stable arc.[31]

The selection of a shielding gas depends on several factors, including the type of material being welded, joint design, and desired final weld appearance. Argon is the most commonly used shielding gas for GTAW, since it helps prevent defects due to a varying arc length. When used with alternating current, argon shielding results in high weld quality and good appearance. Another common shielding gas, helium, is most often used to increase the weld penetration in a joint, to increase the welding speed, and to weld metals with high heat conductivity, such as copper and aluminum. A significant disadvantage is the difficulty of striking an arc with helium gas, and the decreased weld quality associated with a varying arc length.[31]

Argon-helium mixtures are also frequently utilized in GTAW, since they can increase control of the heat input while maintaining the benefits of using argon. Normally, the mixtures are made with primarily helium (often about 75% or higher) and a balance of argon. These mixtures increase the speed and quality of the AC welding of aluminum, and also make it easier to strike an arc. Another shielding gas mixture, argon-hydrogen, is used in the mechanized welding of light gauge stainless steel, but because hydrogen can cause porosity, its uses are limited.[31] Similarly, nitrogen can sometimes be added to argon to help stabilize the austenite in austenitic stainless steels and increase penetration when welding copper. Due to porosity problems in ferritic steels and limited benefits, however, it is not a popular shielding gas additive.[32]

Materials

Gas Tungsten Arc Welding is most commonly used to weld stainless steel and nonferrous materials, such as aluminum and magnesium, but it can be applied to nearly all metals, with a notable exception being zinc and its alloys. Its applications involving carbon steels are limited not because of process restrictions, but because of the existence of more economical steel welding techniques, such as gas metal arc welding and shielded metal arc welding. Furthermore, GTAW can be performed in a variety of other-than-flat positions, depending on the skill of the welder and the materials being welded.[33]

Aluminum and magnesium

Aluminum and magnesium are most often welded using alternating current, but the use of direct current is also possible,[34] depending on the properties desired. Before welding, the work area should be cleaned and may be preheated to 175 to 200 °C (347 to 392 °F) for aluminum or to a maximum of 150 °C (302 °F) for thick magnesium workpieces to improve penetration and increase travel speed.[35] Alternating current can provide a self-cleaning effect, removing the thin, refractory aluminum oxide layer that forms on aluminum within minutes of exposure to air. This oxide layer must be removed for welding to occur.[35] When alternating current is used, pure tungsten electrodes or zirconiated tungsten electrodes are preferred over thoriated electrodes, as the latter are more likely to "spit" electrode particles across the welding arc into the weld. Blunt electrode tips are preferred, and pure argon shielding gas should be employed for thin workpieces. Introducing helium allows for greater penetration in thicker workpieces, but can make arc starting difficult.[35]

Direct current of either polarity, positive or negative, can be used to weld aluminum and magnesium as well. Direct current with a negatively charged electrode (DCEN) allows for high penetration.[35] Argon is commonly used as a shielding gas for DCEN welding of aluminum. Shielding gases with high helium contents are often used for higher penetration in thicker materials. Thoriated electrodes are suitable for use in DCEN welding of aluminum. Direct current with a positively charged electrode (DCEP) is used primarily for shallow welds, especially those with a joint thickness of less than 1.6 mm (0.063 in). A thoriated tungsten electrode is commonly used, along with pure argon shielding gas.[35]

Steels

For GTAW of carbon and stainless steels, the selection of filler material is important to prevent excessive porosity. Oxides on the filler material and workpieces must be removed before welding to prevent contamination, and immediately prior to welding, alcohol or acetone should be used to clean the surface.[36] Preheating is generally not necessary for mild steels less than one inch thick, but low alloy steels may require preheating to slow the cooling process and prevent the formation of martensite in the heat-affected zone. Tool steels should also be preheated to prevent cracking in the heat-affected zone. Austenitic stainless steels do not require preheating, but martensitic and ferritic chromium stainless steels do. A DCEN power source is normally used, and thoriated electrodes, tapered to a sharp point, are recommended. Pure argon is used for thin workpieces, but helium can be introduced as thickness increases.[36]

Dissimilar metals

Welding dissimilar metals often introduce new difficulties to GTAW welding, because most materials do not easily fuse to form a strong bond. However, welds of dissimilar materials have numerous applications in manufacturing, repair work, and the prevention of corrosion and oxidation.[37] In some joints, a compatible filler metal is chosen to help form the bond, and this filler metal can be the same as one of the base materials (for example, using a stainless steel filler metal with stainless steel and carbon steel as base materials), or a different metal (such as the use of a nickel filler metal for joining steel and cast iron). Very different materials may be coated or "buttered" with a material compatible with particular filler metal, and then welded. In addition, GTAW can be used in cladding or overlaying dissimilar materials.[37]

When welding dissimilar metals, the joint must have an accurate fit, with proper gap dimensions and bevel angles. Care should be taken to avoid melting excessive base material. Pulsed current is particularly useful for these applications, as it helps limit the heat input. The filler metal should be added quickly, and a large weld pool should be avoided to prevent dilution of the base materials.[37]

Process variations

Pulsed-current

In the pulsed-current mode, the welding current rapidly alternates between two levels. The higher current state is known as the pulse current, while the lower current level is called the background current. During the period of pulse current, the weld area is heated and fusion occurs. Upon dropping to the background current, the weld area is allowed to cool and solidify. Pulsed-current GTAW has a number of advantages, including lower heat input and consequently a reduction in distortion and warpage in thin workpieces. In addition, it allows for greater control of the weld pool, and can increase weld penetration, welding speed, and quality. A similar method, manual programmed GTAW, allows the operator to program a specific rate and magnitude of current variations, making it useful for specialized applications.[38]

Dabber

The dabber variation is used to precisely place weld metal on thin edges. The automatic process replicates the motions of manual welding by feeding a cold or hot filler wire into the weld area and dabbing (or oscillating) it into the welding arc. It can be used in conjunction with pulsed current, and is used to weld a variety of alloys, including titanium, nickel, and tool steels. Common applications include rebuilding seals in jet engines and building up saw blades, milling cutters, drill bits, and mower blades.[39]

See also

- List of welding processes

- Gas metal arc ("MIG"/"MAG") welding

- Shielded metal arc ("stick") welding

- Oxy-fuel welding

- Friction stir welding

References

- ^ Weman 2003, pp. 31, 37–38

- ^ Hertha Ayrton. The Electric Arc, pp. 20 and 94. D. Van Nostrand Co., New York, 1902.

- ^ a b Anders, A. (2003). "Tracking down the origin of arc plasma science-II. early continuous discharges". IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science. 31 (5): 1060–9. Bibcode:2003ITPS...31.1060A. doi:10.1109/TPS.2003.815477. S2CID 11047670.

- ^ Great Soviet Encyclopedia, Article "Дуговой разряд" (eng. electric arc)

- ^ Cary & Helzer 2005, pp. 5–8

- ^ a b c Lincoln Electric 1994, pp. 1.1-7–1.1-8

- ^ U.S. patent 2,274,631

- ^ Uttrachi, Gerald (2012). Advanced Automotive Welding. North Branch, Minnesota: CarTech. p. 32. ISBN 1934709964

- ^ Cary & Helzer 2005, p. 8

- ^ a b Lincoln Electric 1994, pp. 1.1–8

- ^ Miller Electric Mfg Co 2013, pp. 14, 19

- ^ Cary & Helzer 2005, p. 75

- ^ Miller Electric Mfg Co 2013, pp. 5, 17

- ^ a b Lincoln Electric 1994, pp. 5.4-7–5.4-8

- ^ Jeffus 2002, p. 378

- ^ Lincoln Electric 1994, pp. 9.4–7

- ^ Vel´azquez-S´anchez, Alberto (June 26, 2021). "Dominant Heat Transfer Mechanisms in the GTAW Plasma Arc Column". Plasma Chemistry and Plasma Processing. 41 (5): 1497–1515. doi:10.1007/s11090-021-10192-5. S2CID 235638525. Retrieved April 9, 2023.

- ^ a b Cary & Helzer 2005, pp. 42, 75

- ^ Cary & Helzer 2005, p. 77

- ^ Watkins & Mizia 2003, pp. 424–426

- ^ Minnick 1996, pp. 120–21

- ^ a b c Cary & Helzer 2005, pp. 74–75

- ^ a b c Cary & Helzer 2005, pp. 71–72

- ^ Cary & Helzer 2005, p. 71

- ^ a b c d e f g Minnick 1996, pp. 14–16

- ^ ISO 6848; AWS A5.12.

- ^ Jeffus 1997, p. 332

- ^ a b c d Arc-Zone.com 2009, p. 2

- ^ AWS D10.11M/D10.11 - An American National Standard - Guide for Root Pass Welding of Pipe Without Backing. American Welding Society. 2007.

- ^ Cary & Helzer 2005, pp. 72–73

- ^ a b c Minnick 1996, pp. 71–73

- ^ Jeffus 2002, p. 361

- ^ Weman 2003, p. 31

- ^ Kapustka, Nick. "Arc Welding of Aluminum and Magnesium" (PDF). EWI. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 12, 2019. Retrieved August 10, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Minnick 1996, pp. 135–149

- ^ a b Minnick 1996, pp. 156–169

- ^ a b c Minnick 1996, pp. 197–206

- ^ Cary & Helzer 2005, pp. 75–76

- ^ Cary & Helzer 2005, pp. 76–77

Bibliography

- American Welding Society (2004). Welding handbook, welding processes Part 1. Miami Florida: American Welding Society. ISBN 978-0-87171-729-0.

- Arc-Zone.com (2009). "Tungsten Selection" (PDF). Carlsbad, California: Arc-Zone.com. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- Cary, Howard B.; Helzer, Scott C. (2005). Modern welding technology. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education. ISBN 978-0-13-113029-6.

- Jeffus, Larry F. (1997). Welding: Principles and applications (Fourth ed.). Thomson Delmar. ISBN 978-0-8273-8240-4.

- Jeffus, Larry (2002). Welding: Principles and applications (Fifth ed.). Thomson Delmar. ISBN 978-1-4018-1046-7.

- Lincoln Electric (1994). The procedure handbook of arc welding. Cleveland: Lincoln Electric. ISBN 978-99949-25-82-7.

- Miller Electric Mfg Co (2013). Guidelines For Gas Tungsten Arc Welding (GTAW) (PDF). Appleton, Wisconsin: Miller Electric Mfg Co. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-12-08.

- Minnick, William H. (1996). Gas tungsten arc welding handbook. Tinley Park, Illinois: Goodheart–Willcox Company. ISBN 978-1-56637-206-0.

- Watkins, Arthur D.; Mizia, Ronald E (2003). Optimizing long-term stainless steel closure weld integrity in DOE standard spent nuclear canisters. Trends in Welding Research 2002: Proceedings of the 6th International Conference. ASM International.

- Weman, Klas (2003). Welding processes handbook. New York: CRC Press LLC. ISBN 978-0-8493-1773-6.

External links

- Guidelines for Gas Tungsten Arc (GTAW) Welding

- Selection and Preparation Guide for Tungsten Electrodes

- Tungsten Electrode Guidebook: Guidebook for the Proper Selection and Preparation of Tungsten Electrodes for Arc Welding

- Nano- and Submicron Particles Emission during Gas Tungsten Arc Welding (GTAW) of Steel: Differences between Automatic and Manual Process